In June 323 BC, Alexander the Great was in Babylon, at the Palace of Nebuchadnezzar, when he fell suddenly ill and, just like that, the greatest conqueror the ancient world had ever seen was on his deathbed. Alexander did not have an heir. His son, Alexander IV, was born after his death, so since nobody knew if the child would be a boy or a girl, the question immediately arose of who would succeed as the new ruler of the Macedonian Empire.

Alexander’s closest advisors and generals gathered around the dying king and asked him whom his kingdom should go to, but with his last gasp of life, Alexander simply replied: “To the strongest.”

At least, that’s how Diodorus told the tale and, sure, he might have taken a few dramatic liberties, but the core of the issue was the same – Alexander the Great died without an heir. If he truly wanted his empire to be fought over with the victor gaining the spoils, he got his wish because that was pretty much what happened. All of his most powerful generals engaged in a series of prolonged conflicts that became known as the Wars of the Diadochi or Wars of the Successors.

Ultimately, none of them proved to be strong enough to take over all of the conquered lands, so after decades of fighting, the empire of Alexander the Great was partitioned into several smaller kingdoms.

The one we are interested in today is Egypt. It was ruled by Ptolemy I Soter or “Ptolemy the Savior,” who founded the Ptolemaic Dynasty. It became one of Egypt’s most powerful dynasties, ruling for almost 300 years. But, at the same time, it also served as the last dynasty of Ancient Egypt before the kingdom was incorporated into the Roman Republic.

Early Years

Ptolemy was born in 367 BC, somewhere in Macedonia. His mother was Arsinoe, a Macedonian noblewoman who claimed some distant relation to the ruling Argead Dynasty. His father, ostensibly, was Lagus, although there was a rumor floating around that before she married Lagus, Arsinoe was a concubine of Philip II, King of Macedon and father to Alexander the Great. It gets even juicier because Arsinoe was supposedly already pregnant with Ptolemy when she married Lagus, which would mean that Ptolemy and Alexander were half-brothers. It could be true, or it could be something made up by the Ptolemies later on to strengthen their lineage. There was no Jerry Springer Show back then (or the Jeremy Kyle Show for us Brits), so this one remains unanswered.

There’s not much to say about the first half of Ptolemy’s life. However it happened, he became a close friend to Alexander from an early age, while Philip II was still King of Macedon. Alexander trusted and followed Ptolemy’s advice, even when this did not work out in his favor. There is a tale that Philip II once tried to secure an alliance between Macedon and the Satrapy of Caria by marrying one of his sons, Arrhidaeus, to the daughter of the Carian satrap, Pixodarus. However, on Ptolemy’s advice, Alexander intervened and tried to usurp the marriage for himself. Ultimately, both offers fell through and so did the alliance and, as punishment Philip exiled Ptolemy from Macedonia and he did not return until Alexander took the throne in 336 BC.

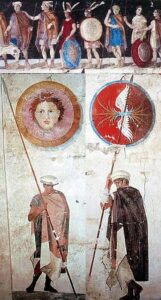

It seems that Alexander did not bear a grudge for the mistake, and when he was the new King of Macedon, Ptolemy became not only a close confidante but one of the king’s somatophylakes aka personal bodyguards. Alexander had seven of these somatophylakes, later adding an eighth, and they were all highly trusted, high-ranking noblemen who acted not only as companions but also as advisers and generals. So yeah, it was a pretty big deal for Ptolemy who got to fight shoulder-to-shoulder with Alexander for most of his conquests. He mainly distinguished himself as a general during Alexander’s campaigns in Persia since that is when Ptolemy was awarded his own independent commands. During the Indian Campaign, Ptolemy was almost killed by a poison arrow, but his life was supposedly saved by Alexander who knew the counterpoison. Again, this might be simple propaganda to show the rest of the world just how buddy-buddy the two of them were.

One day after Alexander had passed away, his advisors got together to discuss the issue of succession and it became pretty clear, right off the bat, that there was no universal solution that everyone would agree with. Some believed that the aforementioned Arrhidaeus, half-brother of Alexander, was the most obvious candidate. Others, however, saw him unfit to rule because he was illegitimate and supposedly had some kind of mental illness.

There was also the matter of Alexander’s unborn child by his Persian Queen Roxana. What if he was a boy? Then, surely, he would have a stronger claim to the throne. Ultimately, after a bit of rabble rabble, it was decided – Arrhidaeus was crowned King Philip III with the understanding that, if Roxana’s baby was a boy (which he was), he would jointly rule as Alexander IV. However, since one of the two kings was an infant and the other was mentally unstable, the actual power went to the new regent, a guy named Perdiccas. He was one of Alexander’s generals and, ostensibly, the guy that the king awarded his signet ring on his deathbed, so it made sense for him to become the new supreme commander. To keep the other generals happy, they were all awarded satrapies in what is known as the Partition of Babylon. Ptolemy, the lucky guy, got one of the richest prizes of all – Egypt, plus Lybia and parts of Arabia. He certainly had no reason to complain, but he foresaw that Perdiccas’s solution would only be makeshift, and that way before King Alexander IV came of age, the other generals would rebel. Therefore, as soon as he was named satrap, Ptolemy got to work to ensure an independent and prosperous Egypt, under his rule.

The First War

Ptolemy’s intuition was proven correct because it didn’t take long at all before some of the other diadochi allied themselves against Perdiccas. They noticed that the regent was trying to legitimize his power grab by marrying Alexander’s full sister, Cleopatra, thus giving him a genuine claim to the throne. They saw the writing on the wall and knew that if Perdiccas’s power kept growing unchecked, it was only a matter of time until he revoked their satrapies and tried to take the entire kingdom. Three of Alexander’s former generals formed a coalition – Antigonus, Antipater, and Craterus.

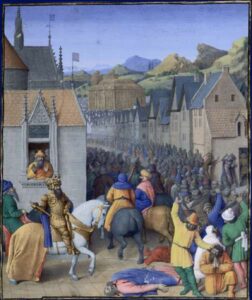

Ptolemy not only joined their alliance but further provoked Perdiccas by stealing Alexander’s body and burying it in Egypt instead of Macedon. The regent was left with no choice but to respond by invading Egypt and, thus, in 321 BC, the First Diadoch War began.

While Perdiccas himself marched to face Ptolemy, he sent another satrap named Eumenes against the armies of Craterus and Antipater. This was where the first shocking moment of the war occurred because nobody in their right mind would have placed money on Eumenes winning. Most of his experience comprised of being Alexander’s personal secretary rather than a battlefield commander, while his opponent, Craterus, was one of the most decorated Macedonian generals of all time. And yet…not only did Eumenes come out on top, but Craterus was killed in battle.

Not a very auspicious start for the coalition, but the tide soon turned in their favor thanks to Ptolemy. He decided to use Egypt’s geography in his favor and engaged Perdiccas at the Nile, preventing him from crossing the river. The regent lost around 2,000 soldiers to the currents and the wild animals, and his men were not happy about it. They saw the war as already lost, so instead of sacrificing themselves to the Nile, they decided it was more prudent to get together and simply stab Perdiccas a bunch of times. Which they did…and just like that, the First Diadoch War was over, and the guy who wanted to assume command after Alexander was dead.

The following day after Perdiccas’s murder, Ptolemy showed up in the Macedonian camp, extending a handshake and offering much-needed carts full of food and supplies. He knew how to get on his enemy’s good side and, during peace negotiations, the opposing commanders even offered Ptolemy the regency. He didn’t want it, though. Ptolemy knew that being regent was just asking for trouble. He was happy with Egypt and, instead, supported two of Perdiccas’s former officers, Peithon and Arrhidaeus, to become the new regents.

Not everyone was happy with this arrangement, though. Specifically, we are talking about Ptolemy’s two remaining coalition members – Antipater and Antigonus. With Perdiccas and Craterus both dead, Antipater was now the most experienced military leader, having served as general since the time of Philip II. He wanted to be regent and he got his wish following the Treaty at Triparadisus, where the satrapies were, once again, redistributed. As expected, Ptolemy kept what he already had, so it didn’t bother him too much, but he knew that a new conflict would not be far behind.

The Second and Third Wars

With the matter of the regency settled, Antipater retired to Macedonia looking forward to some peace and quiet…and then he died in 319 BC. For some reason, he didn’t name his son Cassander as heir, instead awarding his regency to an officer called Polyperchon. As you might expect, the son was not happy with this development, so he sought aid from his father’s former ally, Antigonus, to challenge Polyperchon’s leadership. And thus began the Diadoch War II: The Wrath of Cassander.

Ptolemy also joined the alliance of Cassander and Antigonus although, truth be told, he didn’t have much to do during this conflict since most of the fighting took place further north. He did take advantage of the chaos and attacked the coasts of Syria and Phoenicia to claim some more territory for himself, but that’s about it.

Meanwhile, Polyperchon managed to secure two allies. The first was Eumenes, the general who scored an upset victory over Craterus during the first war. The second was the queen-mother, Olympias who, unsurprisingly, wanted her nephew, Alexander IV, to eventually rule over her son’s former kingdom. She arranged for the assassination of her nephew’s joint king, Philip III, but met her own end when she was captured and executed by Cassander. When he did this, Cassander also captured and imprisoned Alexander’s wife, Roxana, and their son, King Alexander IV, but more on that when we get to the third war.

While all of this was going on, Antigonus handled the lion’s share of the fighting against Eumenes. He emerged triumphant and Eumenes was captured and executed in 315 BC while Polyperchon tucked his tail between his legs and fled to southern Greece where he still had friends.

And so the Second Diadoch War had ended with a significant redistribution of power. Ptolemy might have managed to gain some lands and, by this point, was ruling Egypt as pharaoh in all but name, but his power paled in comparison to that of Antigonus who was now, by far, the strongest of Alexander’s former generals. You know what this means… let’s get a third war going.

This time, the other major diadochi, including Ptolemy, Cassander, and two other guys named Seleucus and Lysimachus, banded together and demanded that Antigonus cede some of his territories to each of them to prevent him from getting too big for his britches. This request went over about as well as you would expect. And thus began the Third Diadoch War.

Just like the second one, Ptolemy tried not to get too implicated, mainly sending reinforcements to his allies and letting them deal with the enemy. However, he had no choice but to get involved at the outset of the war because Antigonus’s first move was to invade Syria and Phoenicia and take over the lands that Ptolemy himself had conquered during the second conflict. At the same time, Ptolemy was dealing with revolts in Cyprus and Cyrene, so he couldn’t focus his attention (and his resources) on Antigonus at the moment.

His opponent took advantage of this opportunity. Antigonus left his son, Demetrius, to fight off Ptolemy should he try to gain back his lands, and he traveled east to battle Seleucus over control of Babylon and the eastern satrapies of Alexander’s former empire. Antigonus also allied himself with his former enemy, Polyperchon, and sent his trusted general, Aristodemus, to help Polyperchon in Greece against Cassander. It’s also worth mentioning here that, at some point, Cassander had his prisoners, Roxana and Alexander IV, executed in secret, which meant the end of the bloodline of Alexander the Great and the Argead Dynasty that had ruled over the Kingdom of Macedon ever since its founding four centuries earlier.

Back to Ptolemy, once he put down the rebellions, he gathered his forces in 312 BC, defeated Demetrius, and regained his lost territories. However, Daddy came to the rescue, and Antigonus showed up in Syria with the full might of his army. Ptolemy decided that discretion was the better part of valor, so he abandoned Syria and returned to Egypt to prepare for a possible invasion.

However, that invasion never came because Antigonus wasn’t after Egypt. What his little heart truly desired was Babylon but he realized that he didn’t have the muscle to take all the other diadochi at once. Therefore, in 311 BC, the Third Diadoch War ended with a less definitive result – Antigonus made peace with Ptolemy, Cassander, and Lysimachus, leaving only Seleucus to deal with.

The Final Wars

The next few years afforded Ptolemy some breathing room as Antigonus fought with Seleucus in the east. He took advantage of this by making gains in Cyprus and the Aegean Sea. In a somewhat surprising result, Seleucus triumphed against Antigonus, but the latter was hardly down for the count. He just took a few years off to rebuild his strength and Antigonus was, once again, in the mood for a little dust-up. He no longer wanted Babylon, though. This time, he set his eyes on another rich prize – Cyprus, which was under Ptolemy’s control.

In 306 BC, Antigonus sent his son, Demetrius, to lead a naval army against Cyprus, which was being defended by Ptolemy’s brother, Menelaus. Demetrius defeated Menelaus in battle, forcing him to retreat to the city of Salamis, where he laid siege. Menelaus managed to hold out until Ptolemy arrived with reinforcements. At that point, the brothers had the numbers advantage but Demetrius took a gamble which paid off big time for him – as soon as Ptolemy’s fleet was in sight, he immediately charged at it head-on so it wouldn’t have time to link up with his brother’s troops. Demetrius scored a shocking victory over Ptolemy who, once again, retreated to the relative safety of Egypt to lick his wounds, leaving Menelaus with no other option than to surrender.

With Cyprus under their dominion, it became clear that Antigonus and Demetrius were the dominant force in the region. By this point, word had also got out that Cassander had Roxana and Alexander IV executed. With the young king dead and Alexander the Great’s lineage wiped out, there was no more need for a regent and no more need for the diadochi to pretend that they were trying to save Alexander’s kingdom or do anything other than gain power for themselves. Therefore, Antigonus and Demetrius held a ceremony and officially declared themselves kings over their domain. Antigonus even started building his own city, Antigoneia, on the banks of the Orestes, much like Alexander had done before him.

When the other diadochi heard of this, they, too, declared themselves kings. Well, in Ptolemy’s case, he became a pharaoh… something which, you know, he already was, unofficially. Ptolemy had the job for years but it was nice to finally get the fancy title, too.

At this point, Alexander’s empire was no more, having split into five different kingdoms – Ptolemy had Egypt, Cassander had Greece, Antigonus had Asia Minor, Seleucus had Babylon, and Lysimachus had Thrace. It could have ended peacefully right then and there, but Ptolemy knew that, eventually, someone’s greed and lust for power would get the better of them. And surprise, surprise, it was Antigonus again. After all, he was the strongest of them all. Why should he have to settle for less? Why not try to take it all in one final war between the diadochi?

Antigonus was feeling extra cocky at the moment and decided to attempt a conquest of Egypt itself. This made sense. Ptolemy was almost defenseless at the moment after losing most of his fleet at Salamis. If there was ever a time to defeat Ptolemy, it was now, but Mother Nature had other plans. Antigonus decided to march with a giant land army to Egypt, while Demetrius accompanied him by sea to set up a two-pronged attack. However, violent storms prevented the fleet from getting close to Egypt and there was more bad news for Antigonus. In order to make the marching easier and faster, most of the supplies were aboard the ships. Once he lost contact with Demetrius, Antigonus was no longer able to feed his soldiers. To prevent his army from perishing in the desert, a red-faced Antigonus was forced to turn back. For the second time, Ptolemy had repelled an invasion of his kingdom without any actual fighting, as it was Egypt itself that did the heavy lifting.

Once bitten twice shy, Antigonus decided maybe skip Egypt for now and, instead, focused his attention on the Aegean. Specifically, he wanted to capture the citadel of Rhodes since it was loyal to Ptolemy and could help him rebuild his fleet. He sent Demetrius to lay siege for a whole year but he could not get the job done since Ptolemy and the other diadochi kept sending reinforcements. Eventually, Demetrius lifted the siege and moved on to Greece to duke it out with Cassander.

As per his regular strategy, Ptolemy tried to get involved as little as possible. The ultimate showdown occurred at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC, in Anatolia. Everyone who was anyone was there – Antigonus and Demetrius on one side, Cassander, Lysimachus, and Seleucus on the other, hence why this skirmish is sometimes referred to as the Battle of the Kings. That is…everyone except Ptolemy, who thought his best course of action was to cause a distraction for Antigonus by attacking Syria.

We can’t really pretend this was one of Ptolemy’s finest hours. Sure, he probably would have conquered Syria, but word got back to him that his allies had been defeated and that Antigonus was on his way to him. Thinking that an open battle would surely end in defeat, Ptolemy abandoned his campaign and fled back to Egypt, hoping that the waters of the Nile would protect him once more.

But the word that reached him was false. The coalition had won the day. Not only that, but Antigonus was killed at the Battle of Ipsus, and Demetrius fled to Greece where he still had some supporters. The Fourth Diadoch War had ended and, while his allies were busy dividing Antigonus’s kingdom between them, Ptolemy was on the outside looking in since he was the guy who tucked his tail and ran.

In the end, all he wanted was Egypt and now he had it. The others kept bickering over the next few decades, specifically over who would rule Macedon after Cassander’s death, but this was of little consequence to Ptolemy who was busy building the foundations of his own dynasty.

At the beginning of his rule, Ptolemy moved the Egyptian capital from Memphis to Alexandria. Although he was involved with the economic and administrative issues of all of Egypt, Alexandria was his pride and joy, turning it into one of the new intellectual, scientific, and cultural centers of the world. He began construction on the Great Library of Alexandria, as well as the famed Lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. Ptolemy also remained devoted to his former mentor and commander, Alexander the Great, by instituting a cult of Alexander throughout Egypt and writing his memoirs of the military campaigns of the Macedonian conqueror.

Ptolemy did one puzzling thing in his final years. When it was time to name an heir, he skipped over his eldest son, Ptolemy Ceraunus, and instead named his second son, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, as his successor. We’re not really sure why he did this, although we should point out that, after being snubbed for kingship, Ptolemy Ceraunus fled to the Kingdom of Lysimachus, where he betrayed the king and took part in a conspiracy against him to garner favor with Seleucus, but afterward betrayed Seleucus as well and assassinated him. Not exactly the most trustworthy guy in the world so maybe the elder Ptolemy knew what he was doing.

Ptolemy died in his mid-80s, in January 282 BC. He tried his best to establish Egypt as a regional power once again and harken back to its glory days. Little did he know back then that his dynasty would become one of the most enduring in the history of this ancient civilization, ruling for almost 300 years until the death of his most famous descendant, Cleopatra.