Four pale horsemen at dawn rode in from the East. They were scouts from the Red Army vanguard, chasing the invaders all the way back to Germany. It was the 27th of January, 1945. Behind the barbed wire, they found 9,000 prisoners left to die by the SS. That place was called Auschwitz.

Among the survivors, a young Italian.

He had been arrested because he was a resistance fighter. He was deported because he was a Jew. He survived because he was a chemist.

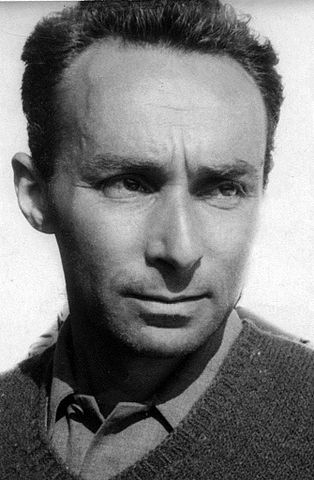

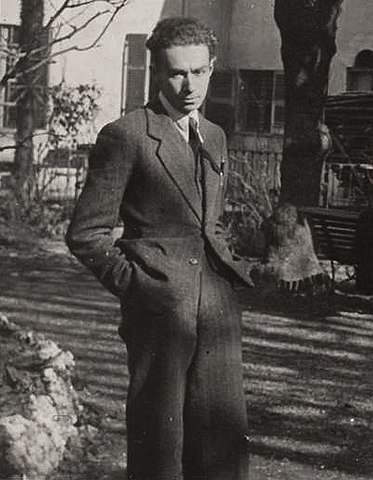

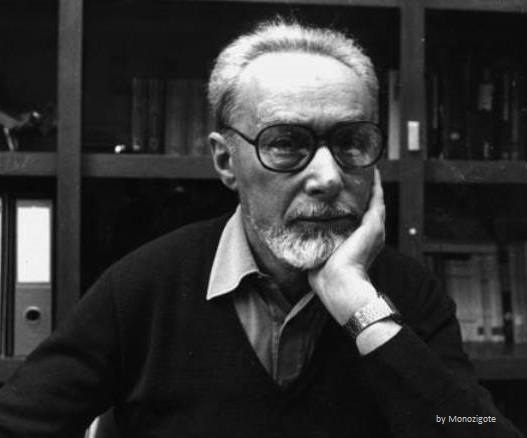

His name was Primo Levi, and he would become one of the most important writers of the 20th Century.

The Young Chemist

Primo Levi was born in Turin, Northern Italy, on July 31, 1919, to a Jewish family of Spanish and French descent. His parents, Ester and Cesare, had married just the year before. Cesare was an extroverted and well-read person with a passion for science.

Primo described his dad as ‘an excellent person, but one who was not suited to a father’s career’.

Nonetheless, Primo inherited from Cesare a love for reading and for science. Both men held a tendency to explore the ‘whys’ of life.

In 1921, Ester and Cesare welcomed their second child, Anna Maria.

Primo would always be very close to his sister. In fact, she was the only familial relationship he did not find … problematic.

Especially as he entered puberty, the studious and introverted Primo found himself in conflict with his outgoing father.

Cesare encouraged his son to “Drink, smoke, go out with girls!”

But Primo preferred to sneak out to a friend’s makeshift laboratory for his first chemical experiments.

Chemistry had, in fact, become his own peculiar way of expressing an early teenage rebellion. His passion for science was rooted in the belief that its study could lead to a deeper understanding of nature, life, the universe.

Moreover, Primo already felt a political undertone to applied chemistry. A rigorous, rational, logical approach contrasted with the irrational soul of the regime in charge – Fascism.

One of Fascism’s key slogans at the time was “Believe. Obey. Fight.”

Primo was not too keen on believing. He first wanted to study and to know.

As per the other two … well, like all his schoolmates, Primo had to ‘obey’ and to ‘fight’ in the training drills of the Fascist Party’s youth organisations.

I should specify that by this stage – the mid-1930s – Mussolini’s Italy had not yet adopted racial laws. Many Jews, especially amongst the middle classes, were staunch Fascist supporters. In fact, a cousin of Primo Levi had been among the founders of the Fascist Movement!

In September of 1937, Primo signed up for Chemistry at the University of Turin.

There, he thrived, enjoying the simple, matter-of-fact language used during lectures. He loved the hours spent in the laboratory, using his hands to assemble lab equipment, to distill elements and create compounds. Time at university also gave him some respite from tensions mounting at home. Primo’s mother, Ester, had found out that her husband Cesare was having an affair.

Ester had a family history of depression and suffered from the illness herself. Cesare’s betrayal only aggravated her status. She projected her hatred of Cesare onto her son, becoming cold, distant, and hostile.

Levi’s biographer Carole Angier believes that it was at this stage that Primo may have started suffering from recurrent clinical depression. This may have been hereditary or triggered by environmental factors.

And factors both at home and outside were definitely stressful.

On September 5, 1938, the Fascist Government issued the first of several ‘racial laws’, meant to discriminate against the Jews.

Primo described his reaction as a trauma: “the trauma of being told: watch out, you are not like the others, you are worse. You are a miser, you are dirty, you are dangerous, foreign, untrustworthy.”

Primo was never openly ostracized at University, but he did endure some isolation. One of the few students who did not avoid him was one Sandro Delmastro. Sandro was not a talented student, so Primo offered to tutor him. In exchange, his friend introduced him to mountaineering.

Primo was rather small, skinny, and scrawny — not exactly a natural outdoorsman. But with Sandro’s coaching, he was able to withstand a gruelling routine after just a few months.

Almost every day, the two would cycle from Turin to the nearby Alps, climb steep mountainsides almost barehanded, and then cycle back at night. During weekends, they camped in the freezing cold, on snow-covered mountaintops.

Soon, World War II had begun. Darkness was encroaching. Primo later called it “The Night of Europe.” As the lights went out in the minds of Europeans, Primo realised that Sandro was training him “for a future made of iron.”

The Amateur Partisan

In 1941, Primo graduated with distinction, but he barely had the time to celebrate. His father was very ill with cancer and could not provide for the family anymore. The young graduate needed to find a job fast, but it was the job that found him. A young Army lieutenant offered him a top-secret job at an asbestos quarry, run by the military.

That was strange enough … the Army employing a Jew? The lieutenant informed him that his job was not … strictly official.

His duty was to analyse the quarry’s waste material and find a way to synthesize nickel. Levi himself could never work out if this job was an Army experiment, or simply an unofficial side gig set up by the Lieutenant.

Nonetheless, he accepted the job, on strict orders to use a false identity and never reveal his religion.

During his time at the quarry, Primo proved his worth by working out an innovative process to extract nickel. His sense of triumph was dampened when he realised that the nickel would benefit the Axis militaries.

In any case, Primo’s superiors shut him down when they found his process too expensive. Primo left the quarry and accepted another job in Milan, carrying the only luggage he cared about: “Moby Dick and few other books, my ice axe, my climbing rope … and my recorder.”

His employer now was a Swiss pharmaceutical firm. Once again, the job was top-secret. And once again, he was instructed not to reveal his identity nor his religion.

His boss, Director Martini, was looking for a chemist to isolate phosphorus from flowers, to produce an oral treatment for diabetes. While Martini was busy fooling around with his secretary, Primo did his best on the job, enjoying the company of co-worker Giulia.

Giulia was a friend from university. It was her who had asked Martini to hire Primo … because she was dead bored and wanted somebody to talk to! By this point, Primo had discovered a natural talent: he was not the most outgoing person to be around … and yet, everybody trusted him, talked to him, told him their stories.

Primo and Giulia spent more and more time together. Alas, like the noble gases, Giulia had no intention to establish a bond – chemical or otherwise – with Primo.

Primo Levi

Firmly friend-zoned by his co-worker, Primo started hanging out with a group of young Jewish men and women in Milan.

In November of 1942, the Allies landed in North Africa. This gave Primo and his friends some hope that the Fascist regime could soon be toppled. It was the prompt for him to join the budding resistance movement in Northern Italy.

On July 9, 1943, the Allies landed in Sicily. Some days later, on the 25th, Mussolini was deposed by his own Grand Council of Fascism, and later arrested by King Victor Emmanuel III.

Primo’s underground activity intensified, working as a liaison agent amongst several factions within the Resistance.

On the 8th of September, new Prime Minister Field Marshal Badoglio announced that an armistice had been signed with the Allies. The Germans were taken by surprise, but quickly occupied Northern and Central Italy, establishing a new puppet state.

The situation was now highly dangerous if you were a Jew. Primo prepared to leave Milan, taking refuge in the Alps. There, he joined a group of partisans operating near the French border.

His unit consisted of 11 fighters: amateurish, poorly trained, and badly equipped, they were marred by distrust among disparate factions. It seems that Primo’s unit was involved in the execution of a supposed infiltrator, although he never offered much in the way of details.

In December of 1943, the rookie partisans welcomed in their ranks a very experienced fighter, who organised extensive firearm drills. This surely increased their skills and confidence … but left them with virtually no ammunition, as much of it was discharged during training.

Their lack of ammo became a critical problem when the Fascist Militia showed up on December the 13th, and Primo and his comrades had virtually nothing with which to fight back. Eight partisans managed to escape, but Primo and two companions were arrested.

It was with little surprise when he discovered the identity of his interrogator: it was that same experienced partisan, who was actually a Fascist spy.

After a long interrogation, Primo admitted being a Jew “partly out of fatigue, but partly out of a surge of haughty pride”

He was deported to the concentration camp of Fossoli thus ending his short partisan career. He later learned that his rock-climbing friend Sandro had also joined the resistance. His career had also been cut short, thanks to the burst of a tommy gun through the back of his head. He had been shot and killed by a 15-year old soldier.

The Fascists in charge at Fossoli treated Primo generally well. But in February of 1944, the SS took over the camp. One day, the Jewish prisoners were suddenly told to get ready. They would be deported the following day.

They only had one night to get ready. Some prepared their luggage; mothers packed food for their children or washed their clothes, leaving them out to dry on the barbed wire. Others, perhaps prescient of the darkness that was to come, found other ways to pass the time. According to Primo, many in the camp ‘took leave from life in the manner which most suited them. Some praying, some deliberately drunk, others lustfully intoxicated for the last time’

Primo and the others wished for that night to never end, but “dawn came upon us like a betrayer.” 650 men, women and children were transferred to the train station. Primo noticed the name of their destination, scrawled on a sign.

A place he had never heard of before. Some place that sounded like ‘Austerlitz’.

But it wasn’t.

The convoy was headed to occupied Europe’s heart of darkness: Auschwitz

The Long Night of Europe

650 deportees, crammed into 12 wagons, traveled four days and four nights. Soon, food was scarce, and water completely absent. Massed like cattle, the deportees had no room to lie down and no privacy for their physiological needs. Their humanity and dignity were gradually dissolved, like so many bodies in hydrofluoric acid.

The train arrived at Auschwitz in the dead of night. The doors opened onto a large platform, and Primo and the other prisoners were subjected to the infamous selection process by a group of SS officers.

Based on age, health, and fitness, the company was divided into two groups. Able-bodied men and women would be sent to labour camps. The others were transferred to Birkenau, where the gas chambers and crematorium were located.

Primo noted how the SS went about their business with methodical calm; they looked like normal police officers. But he also noted how their method of selection was more random than it appeared.

Those who by chance climbed down on a certain side of the convoy, were arbitrarily sent to die.

This is how Emilia, a girl from Milan, died.

Emilia was curious and cheerful.

Emilia was intelligent and ambitious.

Emilia was three years old.

Primo was part of a group of 95 young men, who were taken to a satellite labour camp, 8 km from Auschwitz. 25 young women were taken to a separate location, presumably a female labour camp.

The other 530 prisoners of Fossoli were dead within two days.

Primo’s new destination was called Monowitz, a camp dedicated to the maintenance of a subsidiary plant of chemical giant IG Farben. These laboratory and chemical works were intended to produce a synthetic rubber essential to the German war effort, called ‘Buna.’ Hence, the camp was known also as ‘Buna-Monowitz’

Once there, Primo was subjected to the next stages of the de-humanisation process.

He was stripped of all his belongings, completely shaven and given a striped uniform. The footcloths and underpants had been fashioned out of the ‘tallits’: the sacred shawls used by Jews during prayers. He then received the infamous number tattoo. Primo’s assigned number was 174517.

From then on, Primo and the other prisoners would be referred to only as a series of digits. Or collectively, SS guards simply called them “pieces.” Primo soon realised he needed to sharpen his wits if he wanted to survive. He had to use his reason to tame and contrast the senselessness of his new ecosystem, the camp.

First, it became clear to him that knowing German would put him at an advantage. Prisoners who did not understand orders immediately could be sent to the gas chambers during one of the recurring selections.

Then, Primo learned the value of keeping his feet healthy.

Death started from the shoes.

A callous or blister could degenerate into a nasty infection, leading to death by sepsis.

Those prisoners who did not die immediately developed a limp. They were slower than the rest, always at the back of the queues to collect food. Eventually, they would be picked at selection.

Finally, Levi learned that everybody at Monowitz was a thief. Anybody, even a friend, might steal your loaf of bread, your spoon, your mess tin, or your shoes. Or even a button, thread, wire, or anything else that could be exchanged for more food at the ‘black market’ within the camp.

Besides all that, Primo had to contend with the harshness of hard labour.

The prisoners’ tasks consisted mainly of moving heavy construction material from one place to the other.

The shifts were gruelling, with barely any breaks.

Labourers received a daily food ration of 500 grams of bread kneaded with sawdust, two bowls of watery soup and a little margarine. Nights did not offer respite to their physical exhaustion: prisoners were crammed into overcrowded dormitories, rife with parasites and pathogens of all kinds.

Camp authorities tried to deal with these infestations by disinfecting the dormitories with nitrogen mustard vapour: highly toxic for the inhabitants, and ineffective against the microbes.

Men were supervised at a distance by the SS guards, but their immediate overseers and tormentors were the ‘Kapos’: prisoners selected by camp administration to direct labour, maintain discipline, and, if necessary, harass, punish and humiliate their fellow inmates.

After suffering a foot injury, Primo spent two weeks in the medical block. The experience gave him some respite from hard labour, and the chance to witness the Kapos at work within the infirmary.

The doctors were also prisoners — those who happened to have medical degrees. But the nurses and orderlies had no previous professional experience. They showed no respect for their patients, stealing their food and bartering it for cigarettes or clothes. Often, they would administer beatings to the ill or subject them to humiliating punishments.

If a patient was thought to be dead, two orderlies would beat him with ox sinews for minutes on end, until they were sure that he wouldn’t move any longer.

Even the personnel who operated the infamous shower rooms in the gas chambers were inmates. The SS selected them from among the ‘ordinary’ criminals, rather than the other so-called undesirables. It was they who led the other prisoners inside the showers. It was they who handled the metal containers labelled

‘Zyklon B – For the destruction of all kinds of vermin’

Before putting the gassed bodies into the ovens, a special squad cut off their hair and extracted their gold teeth.

The ashes were then scattered in fields and gardens, as a fertilizer for the soil.

To Blunt the Weapons of the Night

No man is an island, so despite his intelligence and adaptability, Primo could not survive on his own. He needed friends, and even in that hell, he was able to find some remarkable companions.

People like Lorenzo, a civilian construction worker. Risking his own life, Lorenzo managed to smuggle extra rations of food to the scrawny Primo, allowing him to survive while he was injured and hard up.

There was also Jean, a French inmate in charge of transporting food rations. Jean wanted to learn Italian, so he pulled some strings to have Primo assigned to help with his relatively light duties. In a memorable moment, while transporting a vat of soup, Primo taught Jean about Dante’s Divine Comedy and recited to him a canto from the Inferno.

But Primo’s best friend in Monowitz was another Italian Jew, Alberto Dalla Volta. Unlike Primo, Alberto was extroverted and gregarious, a chronic optimist who was able to communicate and network with everybody within the camp. All this, without knowing how to speak German nor Polish!

Alberto’s positive energy on the face of despair was so overwhelming that Primo described him as one ‘against whom the weapons of the night were blunted.’

At the end of 1944, Primo had his life saved by science. Camp authorities were looking for prisoners with a knowledge of chemistry, to work within the Buna labs. He eagerly volunteered, sat an exam, and was accepted for the role.

It was still slave labour, but one that could be carried indoors, rather than in the ruthless Polish winter.

Primo was under strict supervision, yet he managed to carry out small acts of sabotage. Not that they were needed: constantly harassed by Soviet bombing raids, the Buna plant never produced a single gram of synthetic rubber.

When the air raid sirens blared, the German supervisors rushed to the shelters, while Primo and the other prisoners were left in the lab. Luck was again on his side, for he survived also the bombs of the enemies of his enemies. Moreover, he had the chance to explore the lab, scavenging for useful loot.

Primo developed a plan to use lab supplies for food. He experimented by eating cotton fritters or glycerine, which were nutritious … but disgusting. One day he stumbled upon some small metal rods and he brought them to Alberto.

The two friends realised they were made of a cerium alloy, the same material used as flint in cigarette lighters. The ever-resourceful Alberto found out that some prisoners had set up a clandestine workshop to produce lighters!

Risking execution, Primo and Alberto stole all the rods and sold them on the black market in exchange for bread. Enough bread, Primo reckoned, to keep them alive for an extra couple of months.

It was January of 1945, and the Soviets were at the gates. The SS received orders to evacuate Auschwitz and all its dependents. Just on the eve of relocation, Primo fell ill with scarlet fever, and was left to die in the camp infirmary.

Alberto and 11,000 prisoners were to be transferred to another camp. The two friends bade farewell to each other one last time. Primo was certain that he was going to die, while Alberto might ultimately move on and survive.

This was not the case.

The few SS left at the infirmary were ordered to kill all the patients but left the camp in a hurry as the Soviets approached.

On the other hand, most of the 11,000 prisoners on the move were slaughtered in what became a death march. Alberto was one of them. The night that had failed to pierce him, eventually swallowed him.

In the final days in the Monowitz infirmary, Primo partially recovered from his bout with Scarlet Fever. Alongside a French friend, Charles, he did his best to help the other patients in the infectious diseases ward by scavenging food and medicines from the abandoned SS barracks. Only one out of the inmates in their care died.

As Primo and Charles were burying him in the snow, they met the gaze of the four Soviet scouts on horseback.

It was January 27.

Now in the care of Russian liberators, Primo and other Italian prisoners were well treated … but it took seven months for them to return home!

Due to disorganisation and lack of working railways, Primo meandered through Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, Romania, Hungary, and Austria before reaching Turin. The journey was not all unpleasant; on the contrary, the Russians did their best to feed the ex-prisoners, even ensuring they all had a monthly ration of ten ounces of tobacco. Even the children!

The Red Army soldiers, medical personnel, and ex-prisoners also organised film nights, stage plays, and variety shows.

During his Odyssey, as usual, Primo was able to forge alliances with friends impervious to the blows of darkness. He befriended a man who shared the same name as his father, Cesare, who used a mixture of hand gestures, Roman street dialect, and positive enthusiasm to communicate with local tradesmen and hustle for food.

He also met an older man named Mordo Nahum, a rugged Greek veteran. He warned Primo never to be caught bare-footed, because in a war you always need shoes. When Primo noted that the war was over, Mordo replied like a sage:

“War is always.”

A Chemist and a Writer

Primo and other Italian friends reached Turin in August of 1945. His mother and sister, believing him to be dead, barely recognised him.

Almost immediately upon his return, Primo felt compelled to tell his story. He took to writing as a sort of therapy, to cope with the trauma he had survived.

His notes on the medical and sanitary conditions at Monowitz were published in a prestigious medical journal in 1946. His account became known as ‘The Auschwitz Report’ and played a huge part in shining the light on the horrific events of the second world war.

Primo expanded on those notes, drafting his first book, ‘Survival in Auschwitz’. In the preface, Primo warned against the dangers of random, irrational hatred, as it can too easily become the basis for an organised system:

“Many people, many nations can find themselves holding … that every stranger is an enemy … this conviction lies deep down like some latent infection; it betrays itself only in random, disconnected acts, and does not lie at the base of a system of reason.

But when this does come about, when the unspoken dogma becomes the major premise in a syllogism, then, at the end of the chain, there is the Lager.”

The book, in Italy, the UK, and other countries is titled “If this is a man” after a poem authored by Primo. In it, he ponders if a human being can retain his nature even after his dignity has been trampled on.

Primo himself did retain his humanity, slowly returning to life. In September of 1947, he took up a job as a chemist at Siva, a varnish factory. In December, he married his fiancée. This was Lucia Morpurgo, one of the few friends who was eager to listen to his stories of the camps, and who helped him edit his writings.

The two had two children: Lorenza in 1948 and Renzo in 1957.

While working at Siva, Primo succeeded in publishing his memoirs. In 1949, a small publisher released the first edition of ‘Survival’, but with little promotion or interest behind it.

It was only in 1958 that publishing giant Einaudi [Ey-now-dee] widely distributed it, attracting attention abroad.

‘Survival’ was translated into English, French, and — in 1961 — German.

In 1963, Primo released his follow-up to ‘Survival’, known in the US as ‘The Reawakening’. This book recounts Primo’s adventures while returning home after his liberation. Despite the overall positive and lighter tone, there is a dark hue.

The Italian title translates as ‘The Truce,’ which is probably closer to what Primo was going for. He considered the period of his adventures to be, on some level, a truce.

Broadly, this could be a truce between the end of World War II and the onset of the Cold War.

From the perspective of the few survivors of Auschwitz, it was a brief interval, between having lived through the darkness, and having to readapt to society after surviving the darkness.

On an even more personal level, Primo may have felt that his journey was a period of peace, between the cosmic horrors of the Lager, and the intimate struggle of his depression.

As Mordo had said, ‘war is always’.

Following the success of his first books, Primo did not leave his job at the varnish firm, but continued to write, publishing mainly collections of short stories. Many of them could be classed as science-fiction or fantasy.

His most accomplished effort in this genre is ‘Quaestio de Centauri’.

The Narrator forges a friendship with a centaur, kept in captivity. The creature’s human, rational side is usually pre-eminent. That is, until he falls in love with the narrator’s girlfriend. Driven by passion, the animal side emerges and the centaur escapes in a frenzy of lust.

Levi’s most famous story collection, though, is ‘The Periodic Table’ of 1975. This collection was crowned as the ‘best scientific book ever’ in 2006 by The Royal Institution of Great Britain.

Each story uses chemistry as a metaphor to interpret life and is titled after an element of the periodic table.

For example: ‘Iron’ is about Primo’s friendship with Sandro the rock climber, who trained him for a future made of iron.

‘Sulphur’ is about an engineer at a plant. An unsung hero, he prevents a disastrous accident involving an industrial-sized boiler and a stash of sulphur. In other words, he tames a piece of chaotic machinery with his skill and intellect.

Both ‘Sulphur’ and ‘Quaestio de Centauri’ deal with a recurring theme of Levi’s: the contrast of reason against chaos and irrationality, an eternal struggle without a clear winner.

Keeping the Night at Bay

In the views of biographers Carole Angier and Ian Thompson, Levi saw the power of reason as a dam holding back the dark, irrational force lurking within him. That is, his recurring clinical depression.

According to Angier, Levi’s depression was the result of a troubled relationship with his mother, and of a sexless, frustrating marital life.

Angier’s theses are disputed by many critics, who believe Levi’s depression was hereditary. His grandfather suffered from it and had committed suicide.

Another controversial claim is that the ordeal at Monowitz did not worsen Primo’s depression: on the contrary, it honed his survival skills and intellect. Interestingly, Primo Levi confirmed this to American writer Philip Roth.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s Primo Levi sought medical help to treat his recurring bouts of depression, a fact he kept largely hidden from the public and most friends.

A rare ally in his moments of darkness was German pen pal Hety Schmitt-Maas, who corresponded with him for 17 years, since 1966.

Hety was on a quest to document and understand the crimes of the Third Reich, and especially the involvement of company IG Farben in the Lager system. Thanks to Hety, Primo was able to track down his supervisor at the Buna works, Dr Ferdinand Meyer, who had treated him with some humanity.

Their relationship became a true friendship, as they wrote about their respective marital problems. Hety and Primo met face to face in two occasions, in 1968 and 1971. Hety wrote of their first encounter how the charismatic Primo appeared nervous and depressed three years later.

And yet, Primo’s public persona never betrayed his malady, as he delivered lectures and interviews with a pleasant and humorous demeanour.

The main topic of his public appearances was, of course, the Shoah and the preservation of its memory.

Levi frequently clashed with revisionist historians. Especially those who minimised the cruelty of the Lager system by pointing out that other nations, in other times, had done something similar.

As he did not pull any punches, Primo got in controversy also with Zionists. He did not approve of Israel’s military actions against Palestinians. He famously declared that Palestinians were ‘Israel’s Jews’: they were the new victims of those who had once been persecuted themselves.

War is Always

In 1983, Hety Schmitt-Maas died, aged 65. Her death precipitated another depressive episode for Levi. Nonetheless, he completed what would be his last major work, ‘The Drowned and the Saved’. Published in 1986, it is a collection of essays on the themes of the Lager, survival, and prisoners’ collaboration with their captors.

In January and February 1987, Levi met three times with critic Giovanni Tesio, who interviewed him to prepare a biography. In the interviews, Primo confirmed suffering depression as a teenager, spoke at length about his father, but was quite reticent in talking about his mother.

When Tesio tried to arrange a fourth meeting, Levi declined. He was going through a dark patch; he was suffering too much.

The two would never meet again.

On April 11, 1987, Primo Levi’s body was found. It was lying at the bottom of the stairwell, in the apartment block where he had lived since birth.

The coroner’s report read ‘death by downfall’. The police ruled it a suicide.

Most biographers agree with this, blaming Primo’s suicide on a major depressive episode, brought on by his unresolved, life-long issues. Others find the root of Primo’s illness in the trauma of the Lager. Or dismiss the idea of suicide altogether, believing his death to be an accident.

We will not take sides here, nor delve into the private demons of a man who always wished for his private life to remain just that – private.

What matters to us, and to readers worldwide, is his public legacy and his works, recognised as some of the most important testimonies of the horrors of the Shoah.

Primo Levi reminded us that “It happened, therefore it can happen again: this is the core of what we have to say. It can happen, and it can happen everywhere.”

Mordo Nahum was, unfortunately, right.

War is always.

Even after the horror was revealed, humankind did not learn. Elsewhere, in other times, the unspoken dogma of hatred became a major premise, and other chains were formed.

And at the end of those chains, there was Kolyma.

There were Omarska, Srebrenica and the Kazani Pit.

The Killing Fields in Cambodia and in Rwanda.

Sabra and Chatila, and the list goes on.

War is always, and the weapons of the night are still sharp.

SOURCES

Good biographical article

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2002/06/17/a-hard-case

Extended interview with Primo Levi

https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=mVggu34ZRWEC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

Primo Levi as a Resistance fighter

https://www.avvenire.it/agora/pagine/primo-levi-partigiano-ecco-la-verita

Primo Levi’s The Periodic Table

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/427282.The_Periodic_Table

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-00288-6

Primo Levi’s Survival in Auschwitz (If This is A Man)

https://www.scribd.com/book/307072730

Alberto Dalla Volta

http://www.storiaxxisecolo.it/avagliano/Vocidallager/PagineEbraiche2-12.pdf

Medical report on Auschwitz

https://www.scribd.com/book/290900579

Primo Levi’s The Reawakening (The Truce)

https://www.wuz.it/riassunto-libri/8867/tregua-primo-levi.html

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2006/oct/14/primolevi

Hety S and Primo Levi

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2007/apr/07/history.primolevi

Overview of Levi’sWorks

http://bim.comune.imola.bo.it/content.php?current=15321&print=1

Carole Anger and Ian Thompson

https://www.lindiceonline.com/speciali/ian-thomson-primo-levi-vita/

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2002/06/17/a-hard-case

Last days of Primo Levi