In November 1910, Mexico exploded. Triggered by a rigged election, the Mexican Revolution shook the nation. You’ve probably heard of its most-famous sons: Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa. You probably even know its biggest set-pieces, such as the 1914 US occupation of Veracruz. But how much do most of us know about the guy who started it all? About the guy whose rule convinced hundreds of thousands of Mexicans to take up arms and fight to overthrow him?

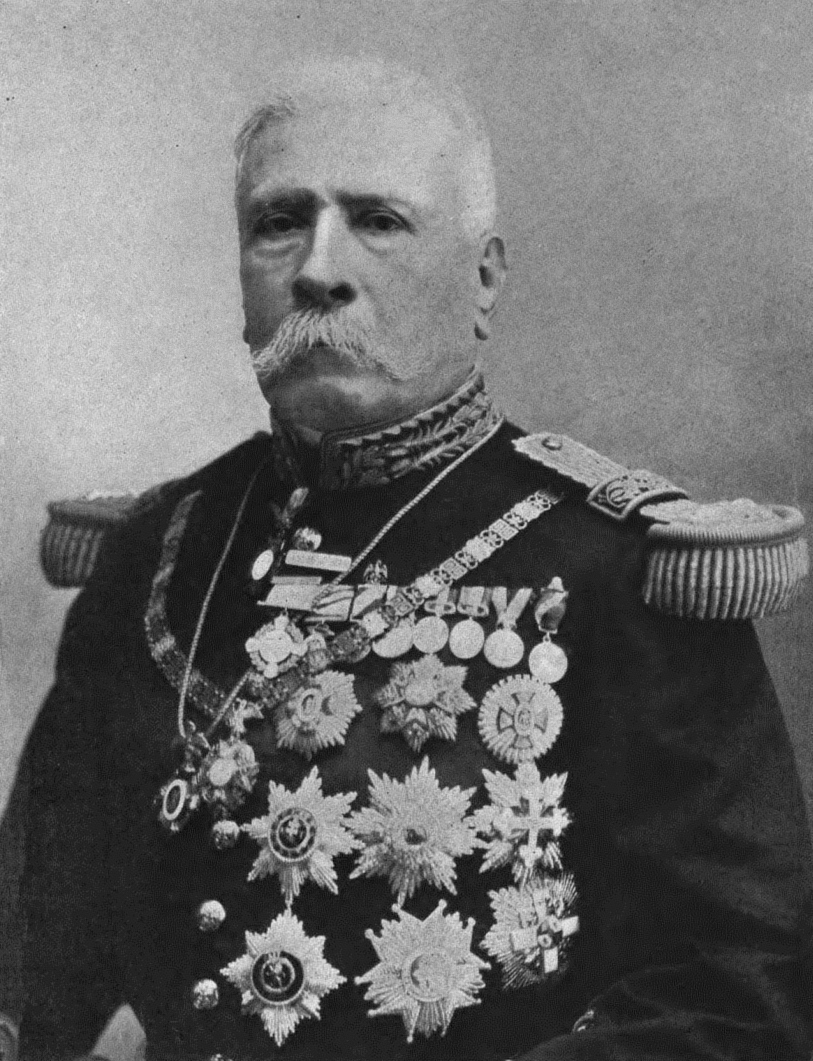

Born in 1830, Porfirio Diaz began life as a poor nobody before rising to become his country’s absolute dictator. Starting in 1876, Diaz ruled Mexico with an iron fist for over three and a half decades, leaving power only when swept from it by the tides of revolution. Yet the story of Diaz is more than just the story of an autocrat. Although a strongman, Diaz oversaw one of the most-sustained periods of progress in Mexican history. Under his watch, the country modernized and transformed… even as democracy was trampled into the dust. A devil to some, an angel to others, this is the life of Porfirio Diaz: Mexico’s gentleman dictator.

Chaos Nation

If you were a gambler, the odds you’d have given on newborn Porfirio Diaz one day ruling Mexico would’ve been somewhere in the region of several quintillion to one.

When Diaz was born on September 15, 1830, it was to dirt-poor mestizo parents in the state of Oaxaca. If you’re not up on your terminology, “mestizo” means mixed-race. Diaz’s ancestors had been a combination of white Spaniards and indigenous Mixtec people.

But while that might sound interesting today, in early Mexico it was pretty much a guarantee that you were gonna spend your life wallowing in poverty. And wallow the Diazes did. When he was just three or five, Diaz’s carpenter father died, leaving the family penniless.

The family was so poor that they couldn’t afford shoes. There are tales that, as a child, Diaz spied on a local cobbler, trying to figure out how to make shoes for his family himself. But then life wasn’t a picnic for anybody in 1830s’ Mexico. The reason being that the country was just embarking on a solid half-century of chaos.

OK, so, in order for us all to really understand what’s going on, we need to take a quick stroll through Mexican history.

Until only a decade before Porfirio Diaz’s birth, Mexico had been the Viceroyalty of New Spain, an outpost of the Spanish empire. But that empire had lost its jewel in 1821, when New Spain had won independence and declared itself Mexico.

The early years of Mexico had been kinda like watching a confused middle schooler, trying on various personalities to see what sticks. It had been an empire, been a republic. By the time Porfirio Diaz was old enough to be spying on shoemakers, though, it had settled into a much-less welcome form.

Mexico was a mess.

The trouble had begun with 1828’s disputed election. What started as a democratic wobble soon became the norm, until Mexico was like a big plate of political Jell-o. To give you some idea just how shaky things were; between 1828 and 1857, the Mexican presidency changed hands fifty times.

This chaos was helped by a number of factors, both internal and external.

Externally, there were all the European powers who kept invading, like the Spanish in 1829, or the French in 1838. Internally, there was the fact that Mexico’s liberals and conservatives would rather focus on dicking one another over than actually governing the country.

Then there was Santa Anna.

You might recognize Santa Anna from your American history class. He’s the Mexican dictator who laid siege to the Alamo and lost Texas to a bunch of revolutionaries.

But he was also Mexico’s great political survivor. Flitting between left and right, he tumbled in and out of the presidency all the way from 1833 to 1855, adding to the general sense of chaos.

But if the decade of Porfirio Diaz’s childhood was characterized by a Mexico constantly on the brink of crisis, it had nothing on what was gonna come next. The 1840s would see the start of a period when Mexico was more or less constantly on fire.

And, when the entire country was nothing but ashes, Porfirio Diaz would be the only person left standing.

The Inferno

There’s a parallel universe where typing “Porfirio Diaz” into Google will get you nothing but a list of obscure Mexican priests. Not in this universe, though. In this universe, Diaz’s teenage attempts to join a seminary were interrupted by war.

On 25 April, 1846, a group of American soldiers deliberately wandered into the disputed zone between Mexico and the newly-annexed state of Texas.

When the Mexican border guards opened fire, the US used it as a pretext to launch a full-scale war.

If Mexico in 1846 was a wobbly stack of Jell-o, then the Mexican-American War was like a hurricane blowing the entire pantry away. The American invasion caused the government to collapse, allowing Santa Anna to seize the presidency for the ninth time.

Down in Oaxaca, 15-year old Porfirio Diaz abandoned the priesthood and instead enlisted in a student militia to fight for Mexico’s honor.

But this wasn’t the war Diaz was destined to shine in. Heck, he wouldn’t even become the biggest name from his home in Oaxaca.

That honor would fall to Benito Juarez.

Born in 1806, Juarez was from a fully indigenous family – unlike the mestizo Diaz – and hadn’t spoken Spanish until he was 12. He was, however, ferociously intelligent, and had become a lawyer and leading liberal in Oaxaca.

Come 1846, Juarez had been elected state governor, just in time for the Mexican-American War.

When it became clear that Mexico was destined to lose, Juarez made a stand and refused to send any more young Oaxacan men to die in Santa Anna’s army. The result was Juarez landing a place on both Oaxaca’s unofficial list of Liberal heroes, and Santa Anna’s very official list of “Guys I’m Totally Gonna Kill.”

On February 2, 1848, the war ended, and Porfirio Diaz demobilized from his student militia.

But rather than return to the priesthood, he instead returned to Oaxaca, determined to follow in Benito Juarez’s liberal footsteps.

Today, Diaz is associated with Mexico’s conservatives, but he started out learning at Juarez’s feet. This gave Diaz a front row seat for Santa Anna’s next vindictive move – and, yes, emphasis fully on the dick. In 1853, Santa Anna returned to the presidency for the first time since the war.

Only this time, he styled himself “His Serene Highness,” and launched a brutal consolidation of power. A consolidation that included kicking Benito Juarez out the country.

When Diaz heard his mentor was being forced into exile, he was livid.

He marched down to the town square where a referendum was taking place on Santa Anna’s coup – watched over by Santa Anna’s armed soldiers, naturally – and openly cast a vote against the dictator.

In the chaos that followed, Diaz then managed to mount a horse, steal a gun, and shoot his way out the town and off into the mountains to foment rebellion.

It was both the most-Mexican exit we’ve ever heard, and a piece of excellent political timing.

Santa Anna’s new regime was as unpopular as a president returning for the eleventh time tends to be. When others took up arms against him, it was clear his time was over. In 1855, Santa Anna resigned and fled into exile. He would die in poverty in 1876, having never regained the presidency.

In the aftermath of Santa Anna’s two decade hold on politics collapsing, the Liberals took power. Juarez came back to Mexico, Diaz came back down out the mountains, and everyone cheered.

It should’ve been a moment of calm. A hard-earned bit of breathing space after decades of chaos.

But this is 19th Century Mexico we’re talking about.

And if there’s one thing 19th Century Mexico was all about, it was chaos.

A Warrior’s Rise

When the Liberals took power in the wake of Santa Anna’s fall, they weren’t in the mood for compromise.

They promulgated a new, hyper-liberal constitution that not only guaranteed free speech and the right to bear arms but also stripped the Catholic Church of its power and property. Unfortunately for Diaz and Juarez, Mexico had a lot of Catholics. A lot of Conservative Catholics now sure that this Liberal government was destroying their way of life.

And so we come to war #3,792 of this video: the Reform War. Trust us, it won’t be the last.

Pitting Liberals against Conservatives in a gigantic bloodletting, the Reform War – or La Reforma – sucked for just about everyone.

But not for Porfirio Diaz.

Well, it did physically. In one early battle he got shot, leaving a festering wound in his side that wouldn’t heal for two whole years.

Yuck.

But, politically, the war paid dividends. When La Reforma ended in 1860 with a Liberal victory, Diaz was promoted for his heroism. That meant he became a general just in time for the French invasion of Mexico. Yep, its more war, this time courtesy of our old friend, Napoleon III.

After winning the Reform War, Benito Juarez had retaken the presidency and discovered the country was broke. So he suspended all repayments of foreign debts.

However, one of those foreign debts just happened to be held by France, now under the dictatorship of Napoleon’s nephew, Louis-Napoleon.

And if Napoleon III had inherited one thing from his uncle, it was his love of invading foreign nations.

We don’t have time to go into the French invasion in detail – which is a shame as its super interesting, and involves Louis-Napoleon proclaiming a bewhiskered Austrian named Maximilian Emperor of Mexico. If you want to learn more, check out our video on Maximilian.

For now, though, we’re gonna touch on one key date you’ve definitely heard of: Cinco de Mayo. If you live north of the border, there’s a good chance you only know Cinco de Mayo as the day frat boys don sombreros and get hammered on tequila.

But it was also the date of the Battle of Puebla.

On May 5, 1862, the Mexican Army faced the French in a battle where they were outnumbered 3 to 1. General Porfirio Diaz was technically second in command of the Mexicans. But, really, it was thanks to him that we celebrate Cinco de Mayo at all.

At the climax of the fighting, Diaz single-handedly led a cavalry charge against the French. So daring was his attack that the French lines broke, resulting in a Mexican victory.

The Battle of Puebla raised Porfirio Diaz from being a mere Liberal icon to a folk hero for the entire nation. It helped that Diaz followed his win up with escapades like getting captured and breaking out of prison twice. By the time the French abandoned their Mexican adventure, Porfirio Diaz was to Mexico what Davy Crockett is to America.

And he knew this. When the post-invasion election of 1867 was held, Diaz threw his hat into the ring. He probably should’ve won.

The only reason he didn’t is that Benito Juarez also ran. While Diaz might’ve been a folk hero, Juarez was the nation’s wartime leader.

It was like FDR asking the American public for his fourth term. Of course Juarez was gonna win. So Diaz backed down. He stepped out the race and retired to a ranch in Oaxaca.

But here’s the thing. Porfirio Diaz in 1867 wasn’t retirement age. He wasn’t even 40.

More than that, he was ambitious. More ambitious than Benito Juarez realized. In less than a decade, that ambition was gonna take him from “Mexican folk hero” to “bigger dictator than Santa Anna.”

“No Reelection!”

If we’ve done our job, by now it should be clear that Mexico in the mid-19th Century was near-ungovernable.

The entire period from 1828 onwards had been nothing but invasions, wars, coups, dictators, and imposed emperors. When Porfirio Diaz finally seizes power in five minutes’ time, you might wonder why no-one goes into rebellion against him. Why there’s no great war against his dictatorship.

Well, ask yourself this. If you’d lived through all that chaos, would you really be itching for another war?

Four years after Diaz retired to his ranch, in 1871, another election rolled around. At this point, Benito Juarez had effectively been in power since La Reforma, a near 15-year run. It was widely expected that he would step aside to allow some fresh blood. Someone like, oh, I dunno, a certain moustachioed general living on his ranch in Oaxaca?

But, no. Come 1871, Juarez stood for reelection.

It was at this point that Diaz snapped.

Back in 1867, Diaz had been deferential to his former patron. This election, the gloves weren’t just off; they’d been filled with dynamite and shoved up Juarez’s ass. Diaz ran on a platform relentlessly attacking Juarez as a dictator in the making, as another Santa Anna.

He made his rallying cry the phrase “no reelection!”, and made limiting presidents to a single term a key part of his pledge.

When Juarez still squeaked to victory, Diaz jumped on his horse, picked up his gun, and rode back off into the mountains to start another rebellion.

Only, it didn’t quite work.

While there were no real battles, the few skirmishes Diaz’s men participated in resulted in the army wiping the floor with them. It’s entirely likely Diaz would’ve just fizzled out, had fate not intervened.

On July 18, 1872, Benito Juarez suffered a heart attack and died at his desk.

With Juarez gone, a dude called Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada took over as president. Luckily, Lerdo was a guy who was all about burying the hatchet.

That summer, Lerdo issued an amnesty for everyone who’d taken up arms against Juarez. Diaz returned from the mountains, presumably thinking the next election was in the bag.

And then 1875 rolled around and Lerdo decided to stand for reelection.

One of the major failures of Diaz’s anti-Juarez rebellion had been a lack of funds. So, this time, Diaz didn’t instantly declare himself in rebellion, but traveled to the USA.

There, he arranged some meetings with some very rich businessmen, and let it be known – very subtly – that, were they to help finance his bid for the top job, he might just start opening up Mexico to wealthy American investors.

Funding secured, Diaz then declared himself in rebellion under his old “no reelection!” slogan.

Tooled up with American guns and money, Diaz’s army was now unstoppable.

But there would be no major battle. When Lerdo saw which way the wind was blowing he was all like “you know what? You can have the presidency.”

Porfirio Diaz finally became president of Mexico in early 1877. One of his first acts was to alter the constitution to make reelection illegal. But while people in 1870s Mexico might’ve thought this proved Diaz was for real with his slogan, from our vantage point in the 21st Century, we can see just how hollow that promise was. Porfirio Diaz was now in power, and he had no intention of giving it up.

Mexico would be under his perfumed boot for the next thirty six years.

The Porfiriato

If you’ve seen Narcos, you’ll recognize Pablo Escobar’s phrase: plata o plomo, meaning “silver or lead”. I.e. work with me and get rich, work against me and get dead.

Well, Porfirio Diaz had his own version.

The period of Diaz’s rule is known today as the Porfiriato, and its unofficial slogan was pan o palo, or “bread or stick.”

The bread part was for Diaz’s old enemies, or others who might have the power to challenge him. These guys got not only showered with money, but guarantees they could run their power bases like personal fiefdoms, in return for not getting any ideas about being president.

The stick part… well, that was for everyone else.

Peasants who objected to their crops being taken by greedy elites; indigenous villagers worried about haciendas stealing their land; workers who wanted to unionize… they all got whacked with the Porfiriato’s stick.

Not that this meant they were killed. Murder wasn’t Diaz’s style, he was too refined for that.

Nah, what it meant was suddenly having all your property confiscated. Or being deported to do backbreaking labor in some far-flung region without your family knowing where you were. Murder and torture aside, Diaz didn’t really care what happened to you.

He had troublesome villages broken up, their members all separately shipped off to do hard labor.

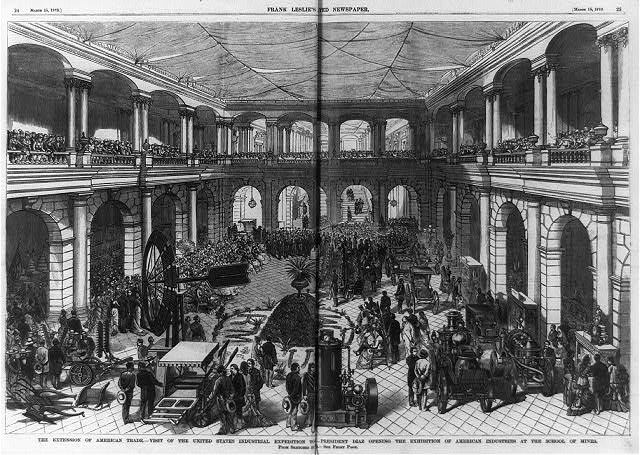

That done, Diaz turned his attention to the second part: attract money into Mexico.

At the start of the Porfiriato, Mexico was deeply in debt, with a poor international reputation.

Diaz made sure all of that changed. He made debt repayments a priority. Then, once people accepted that money invested in Mexico wasn’t money lost, he went back up north to see his American business pals and present them with his grand vision.

They would invest in Mexico, and Diaz would ensure they had monopolies, and that any troublesome workers were dealt with using the Porfirian stick.

In return, these investors would modernize his country.

After all its warring, Mexico had almost missed out on the industrial revolution. There were few rail lines, and some provinces were still so isolated that they were effectively self-governing. But not anymore. Almost overnight, railroad tracks sprang up, linking cities to ports, to the USA. Telegraph poles marched out by the thousands, connecting villages for the first time to the modern world.

Mines opened, digging up silver, zinc and copper by the bucketload.

All this created one of the most sustained economic booms on record. Money was suddenly pouring into a Mexico that was suddenly safe. What was there not to love?

Diaz had gambled that, after a half century of mayhem, Mexicans would accept him trampling civil liberties in return for law and order and a chance to get rich.

And he was right. The reason no-one rebelled against the Porfiriato was because no-one wanted to.

But Diaz’s boom wasn’t evenly distributed.

While the elites, the foreign investors, and the new middle class all got fat on Porfirian bread; millions of peasants, indigenous, and urban poor got nothing but the stick.

Then there was the hypocrisy.

In 1880, Diaz honored his pledge and stepped down, refusing to run for reelection. Instead, he installed a puppet president, and made sure this puppet passed just enough unpopular laws that, come 1884, the people were begging Diaz to return.

So Diaz did as his people asked. And then he amended the constitution to make it legal for the president to have unlimited terms.

So much for “no reelection.”

The Creelman Interview

By 1908, the Porfiriato was less a dictatorship than it was a fact of life. Diaz was now the longest-serving ruler in Mexican history, making even Santa Anna look a novice. As the Porfiriato had ossified, so too had the country.

Democracy had been dead so long that no-one could remember what it looked like. Land rights were a thing of the past. The rich kept getting richer, and the poor kept getting poorer. It was against this backdrop of stagnation and resentment that the 77-year old Diaz gave the interview that would destroy him.

The Creelman interview – by American journalist James Creelman – was meant to be a puff piece. It’s certainly written that way: its portrait of Diaz is so sugar-coated that it should carry a diabetic health warning.

But deep within Creelman’s sycophantic prose was buried a landmine. One that, when it detonated, would blow up the whole of Mexico.

Amazingly, it was planted there by Diaz himself.

“I have waited patiently for the day when the people of the Mexican Republic would be prepared to choose and change their government at every election…” he was quoted as saying. “I believe that day has come.”

The words were vague, meant to reassure readers in the democracy-loving US that Diaz wasn’t a bad guy. But they also gave everyone in Mexico the impression that Diaz wouldn’t stand in the 1910 election. You know that phrase: “when you’re in a hole, stop digging?”

Well Porfirio Diaz was evidently of the “better to dig straight through to Australia” school. When everyone asked if he really was gonna stand aside and let another president take his place, he was all like, “sure, why not?”

He stood by this all through 1909, as new political parties emerged. As a pro-democracy businessman named Francisco I. Madero declared he would run under Diaz’s former slogan of “no reelection!”

Diaz even stood by his words as Madero began campaigning in 1910, drawing enormous crowds of cheering supporters. Maybe Diaz was so blinkered that he assumed he’d win in a fair fight. Maybe he really did want democracy in 1908, then got cold feet as the election approached.

Either way, the result was the same.

Right before the election, Francisco Madero was arrested. On polling day, everyone was given a choice: vote for Diaz, or get a taste of the ol’ Porfirian stick.

But you can’t let a genie like democracy out of its bottle and hope to just stuff it back in. Diaz had given Mexico something unbelievably dangerous, as dangerous as handing the electorate a loaded gun and placing the barrel against his forehead.

He’d given them hope.

On October 5, 1910, Francisco Madero escaped jail and fled into exile in Texas. There, he issued the Plan of San Luis de Potosí, calling on the Mexican people to rise up and overthrow Diaz.

At long, long last, the Mexican Revolution was here.

By the time it ended, no-one would be left standing at all.

The End of Order

You might already know that November 20 is celebrated as Mexico’s day of revolution. What you might not know is that, had you been alive on November 20, 1910, you wouldn’t have realized anything was happening.

That’s because almost nobody in Mexico heeded Francisco Madero’s call. In the capital, the Porfiriato grinded on like nothing had changed.

But “almost nobody” is not the same as “nobody”.

Up in the north, a guy called Pancho Villa decided to follow Madero and get his revolution on. What began as a little bit of disorder quickly snowballed into an all-consuming avalanche. The Army had got fat and lazy on Porfirian bread and forgotten how to fight. Villa and his armies spent the winter racking up victories. By mid-February, Francisco Madero was back in Mexico, ready to lead the revolt.

Yet, even now, Diaz couldn’t see the danger he was in.

He remained blind to it as winter gave way to spring. As Emiliano Zapata’s rebellion broke out in Morelos. Even as Villa’s army laid siege to Ciudad Juarez. It wasn’t until the city was about to fall that Diaz seems to have woken up to the looming threat.

But by then it was too late.

In early May, Ciudad Juarez fell. Around the same time, the Zapatistas captured the city of Cuautla. There were now only two options. Diaz either resigned, or he dug his heels in and plunged Mexico into a bloody civil war.

But Diaz wasn’t a dictator like Syria’s Assad, ready to drown his country in blood to cling to power. He was a gentleman.

And gentlemen knew when to quit.

On May 21, 1911, the treaty of Ciudad Juarez was signed, paving the way for an interim president and new elections. Four days later, on May 25, Porfirio Diaz resigned the presidency and boarded a boat to Europe.

After 36 years, the Porfiriato was over.

As he left, Diaz famously declared of the revolution: “Madero has unleashed a tiger, now let us see if he can control it.”

Spoiler alert: he couldn’t.

In the next two years, Francisco Madero would first become president, then be assassinated by General Victoriano Huerta. Huerta’s coup would be what turned the Mexican Revolution into an inferno, sparking the violence that killed hundreds of thousands.

But all that is a story for another time.

Porfirio Diaz spent the last four years of his life in exile in Paris, watching his former country disintegrate. Possibly with sadness, possibly with a feeling of satisfaction that he’d been right all along: Mexico really was ungovernable.

Diaz finally died on July 2, 1915. He was buried in Montparnasse Cemetery. Today, Porfirio Diaz’s reputation is still unsettled. On the one hand, there are those who point to the stability he brought. To the real economic progress made under his watch.

On the other, there are those who point to the millions left behind by the Porfiriato. The millions abandoned until they got so frustrated that violent revolution was the only option.

Maybe both sides have a point.

Without a doubt, Porfirio Diaz was a dictator. Without a doubt, he squandered the security and progress his regime brought by showering money on a narrow elite. But Diaz was also the lynchpin of an entire era of Mexican history. A guy who ruled for longer than anyone else.

His story may not be a pretty one, or even an inspiring one. But it’s one we need to remember. For better or for worse, without Porfirio Diaz, modern Mexico would be a very different place.

Sources:

Excellent podcast on Mexico pre-Porfiriato, and during the same (multiple parts): https://www.revolutionspodcast.com/2018/08/903-mexico-.html

https://www.revolutionspodcast.com/2018/09/904-the-porfiriato.html

Podcast reading the Creelman interview, includes a (very biased) look at Diaz’s life: https://podcasts.google.com/?feed=aHR0cDovL21leGljb2hpc3Rvcnlwb2RjYXN0LmxpYnN5bi5jb20vcnNz&episode=ODE3YzU2Mjg3ZDEwNGI5MzljYzU5YzY3ZDQ3ZThjMDQ&hl=en-CZ&ved=2ahUKEwiTvfCzsuLnAhXdQ0EAHeZHCrsQjrkEegQIBxAI&ep=6

Britannica’s biography: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Porfirio-Diaz

ThoughtCo Bio: https://www.thoughtco.com/biography-of-porfirio-diaz-2136494

Diaz’s resignation in-depth: https://www.historytoday.com/archive/months-past/ousting-porfirio-d%C3%ADaz

1915 NYT report on Diaz’s death: https://www.nytimes.com/1915/07/03/archives/porfirio-diaz-dies-an-exile-in-paris-ruler-of-mexico-for-30-years.html

Library of Congress materials on Diaz: https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/mexican-revolution-and-the-united-states/mexico-during-the-porfiriato.html

Biographics on Maximilian I: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e3ZJ65c2q8s

Biographics on Emiliano Zapata:

Mexican American War (1846-48): https://www.history.com/topics/mexican-american-war

The Reform War (1858-61): https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/war/mexican-reform.htm

French Intervention in Mexico: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1861-1865/french-intervention

A walk-through of Mexican history: https://www.britannica.com/place/Mexico/Independence#ref27359

The Cientificos: https://www.britannica.com/topic/cientifico