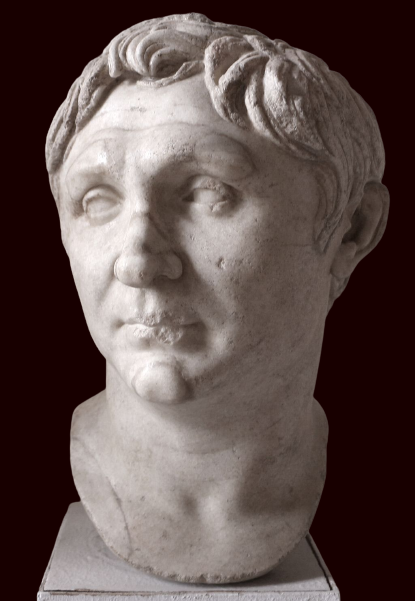

Welcome back to our Biographic on Pompey the Great, one of the most significant figures in the history of Ancient Rome. His career was so prolific that we just had to give it the supersize treatment. Make sure you check out the first part if you haven’t seen it yet, because we are starting this one in medias res, right in the middle of the action, as we get back to the story of Pompey.

Pompey VS Spartacus

The last time we saw our intrepid hero, he had just won the Sertorian War. This alone was worthy of another military triumph back in Rome, but Pompey was not the kind of guy to just sit back and take it easy when there was fighting to be had.

During the years that Pompey had been away in Hispania, a slave rebellion erupted in Italy in 73 BC, started by a few dozen escaped gladiators from a training school in Capua and led by some guy named Spartacus. At first, this was of no particular concern. After all, slave uprisings happened all the time and were usually crushed quickly and mercilessly.

This one, however, was different. Before long, the gladiators were joined by tens of thousands of other warriors and they led raids all over Italy. The Senate’s solution was to send a praetor named Glaber after them with a force of poorly-trained, poorly-equipped militia, thinking that it would do the trick.

In fact, it did not do the trick. It fumbled the trick worse than a drunk magician on “$1 beer night.” Glaber’s militia was annihilated by Spartacus’s forces, and then another praetor sent on a second expedition suffered the exact same fate. If anything, they were helping the gladiator’s cause because his men equipped themselves with the weapons and armors of the dead Romans, while word spread of the mighty Spartacus and made even more people join up.

The following year, Rome sent two consular legions after the slaves. No more militia this time. These were proper Roman soldiers, and yet, the same thing happened. By 71 BC, the Senate realized that they done goofed. By dismissing the revolt in its early stages, they allowed it to grow to dangerous levels. Some estimated that Spartacus’s army may have exceeded 100,000 men and that they were thinking of marching on Rome itself.

This was the time when Pompey would have come in handy, but he was still in Hispania at this point. Therefore, the Senate turned to their second-best option – Marcus Crassus.

Pompey and Crassus had fought together under Sulla and enjoyed a frenemy relationship. They often had to compete for the same goals, but, overall, they both benefited more from having the other one around than from getting rid of him. Crassus accepted the task of ridding Rome of Spartacus and his slave army, and this time there were no half-measures. Crassus went after his target with eight legions of Roman soldiers, plus tens of thousands of auxiliaries.

Crassus gained the upper hand in the conflict and, at one point, had trapped Spartacus and his army in Bruttium and launched a war of attrition, hoping to starve them out. Things were going well until Crassus received terrible news – he was getting reinforcements.

But wait a minute? Wasn’t that good news? Well, no, not really, because the reinforcements consisted of Pompey and his army. He had finished his work in Hispania just in time to take part in the tail end of the Gladiator War and collect his share of the credit. Unsurprisingly, Crassus wanted the glory for himself, but, on the other side, Spartacus wasn’t thrilled with the idea, either, since it meant fighting two armies instead of one. Therefore, the two camps met in combat, once and for all, at the Battle of the Silarius River. Crassus was triumphant and Spartacus, presumably, was killed in battle, since his body was never recovered.

And yet, it was Pompey who had the last laugh. A few thousand slaves managed to slip past Crassus’s forces, and they walked right into Pompey’s army which was just arriving to join the fray. After he diligently slaughtered every last one of them, Pompey sent word to the Senate, saying that “Crassus had conquered the gladiators in a pitched battle, but that he himself had extirpated the war entirely.” This was technically correct (which is the best kind of correct), but he was clearly exaggerating his role in the matter while minimizing that of Crassus.

The latter had no choice but to grin and bear it. He knew that Pompey was more popular than him and he didn’t want to come off as bitter by complaining. Therefore, when they arrived in Rome, Crassus just sat back and watched the city throw another triumph in Pompey’s honor, although truth be told, it was mainly for his actions in the Sertorian War, not the slave rebellion.

Once it was over, Crassus approached Pompey with a smile on his face and an extended handshake and made clear his true intentions. He wanted his support for the position of consul and Pompey was happy to give it to him. In fact, both men were put forward as candidates for consulship the following year. Technically, Pompey should not have been eligible, both due to his young age and because he never held any of the lesser offices, but the entire cursus honorum went out the window when it came to Pompey. Ultimately, a special decree was passed, and in 70 BC, both men were elected consuls.

The most significant thing that Pompey did during his time as consul was to bring back the plebeian tribune, or the tribune of the people. Historically, this was the first office in Rome open to commoners and it was also their greatest check on the power of the upper classes since the tribune could veto the decisions of the Senate and even the consuls. Sulla did away with the position, but both Pompey and Crassus agreed to restore it, to the tremendous pleasure of the Roman people. Apparently, it was the only act during their one-year term in which the two consuls cooperated.

Pompey VS Pirates

Once Pompey’s consulship was over, he was ready to put down the pen and pick up the sword again. He was still in his prime, after all, so there was no reason for him to give up the military life he loved so much. Surely, Rome was always embroiled in one conflict or another and now was no exception as the Republic was fighting the Third Mithridatic War against Mithridates VI, King of Pontus.

Nowadays, Mithridates isn’t particularly well-known, which is a bit unfair since he was one of Rome’s most formidable opponents during its Republic years. He had been a thorn in their side for decades and had waged his first war with Rome against Sulla. Back then, Sulla had the upper hand and could have probably eradicated the problem completely. However, he was rushing to get back to Rome to deal with that pesky civil war, so he hastily agreed to a treaty with Mithridates. Then, in 83 BC, the second war started, but this one was relatively brief and proved inconclusive before each side retreated deep into its own territory again.

That’s how we arrived at the third and final Mithridatic War, the longest of the bunch. It started in 74 BC when Mithridates invaded the neighboring kingdom of Bithynia, which was intended to become a Roman province. But if you are good at remembering dates, you might recall that, at that time, Pompey was in Hispania fighting in the Sertorian War, so he couldn’t also go to Anatolia to fight the Kingdom of Pontus. Therefore, the two consuls of that year, Lucius Licinius Lucullus and Marcus Aurelius Cotta, were sent to deal with the problem. And they did a pretty good job. They defeated Mithridates and pushed him back several times, but couldn’t deal with the threat permanently.

By 69 BC, the war was still going hot and Pompey was raring to go, but there was just one problem – there were no vacancies. Mithridates was one of the Republic’s greatest enemies and taking him down would have been a major feather in the cap or, you know, laurel wreath of any military commander. The guy who pulled that off – that’s the guy getting a Biographics video 2,000 years later and every Roman general knew it. Nobody was willing to give up their spot in the war for Pompey, but that was ok because he had another foe to fight – pirates.

Over the last couple of decades, pirates in the Mediterannean had become an ever-increasing problem for Rome. They were responsible for attacks on vital grain ships, as well as taking prominent Romans prisoners and holding them for ransom. The most famous example was Julius Caesar, who was captured in 75 BC and held captive for over a month.

Like Spartacus and his gladiators, the pirates started out as a minor nuisance. Because of this, Rome assumed it could deal with them at any time, so it left them unchecked until they became a serious threat. Plutarch estimated that, at the height of their power, the pirates had over 1,000 ships and controlled 400 cities. Several Roman commanders tried to subdue the marauders and failed and, in 67 BC, one fleet of pirates got so cocky that they sailed up to the mouth of the Tiber and attacked the port of Ostia near Rome itself.

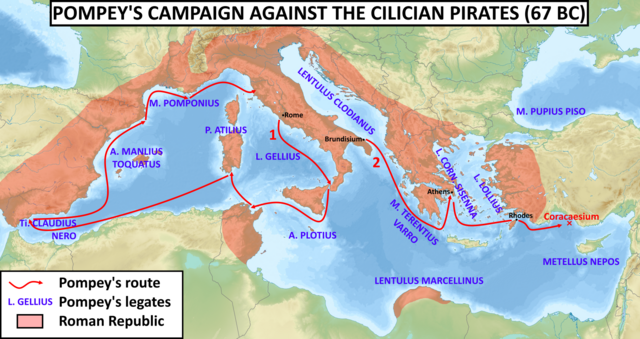

Such an act was considered a great humiliation for the Republic that couldn’t even protect the waters near its capital. Therefore, an extraordinary move was made. A new law was passed – lex Gabinia – which conferred great powers on a proconsul and gave him almost complete control over the port cities in the Mediterranean Sea. This was accompanied by significant financial resources and a large fleet in order to deal with the pirates. And the man who gained these remarkable privileges was none other than Pompey.

Not everyone was thrilled with the decision and many fought fervently to stop the law from passing. They were uncomfortable with the idea of one person having all that authority, and, to be fair, they had a point. Just in the last 20 years or so, there had been several men who rebelled against Rome’s status quo and tried to take power for themselves. Fortunately for the Senate, Pompey was not one such man. Sure, he wanted all the power, money, and glory that he could get, but he was content with doing it within the bounds established by the Roman Republic.

In terms of pure efficiency, this might have been Pompey’s finest hour. He had 200 ships at his disposal and as many soldiers as he needed. He divided the Mediterranean into thirteen districts and each one was assigned a number of ships led by a commander he trusted. Meanwhile, Pompey himself traveled with his sixty best ships to Cilicia on the southern coast of Anatolia, since that was the biggest pirate haven.

Within 40 days, most of the seas were free of pirates. Pompey showed great mercy to those he captured, which prompted many others to surrender willingly since they knew the good times were over. Pompey then needed just a few more months to track down the ones who refused to submit peacefully. Overall, a great success for Pompey, and it was followed by even more good news because the Senate was starting to think that maybe he should deal with Mithridates, after all.

Pompey VS Pontus

It was in early 66 BC that a tribune named Manilius began suggesting that Rome turned over its eastern command to Pompey. As we said, the previous guy, Lucullus, was doing alright, but he suffered a major setback in 67 BC when he lost an important battle that turned the tide in Mithridates’s favor. Some were even accusing Lucullus of prolonging the war intentionally so he could loot and plunder as much as possible. A new law was passed – lex Manilia – which made it official. Pompey was now in charge. Apparently, when he heard of his new appointment, Pompey reacted with mock histrionics, bemoaning the fact that he is always the one who has to take on these massive challenges. He said: “Alas for my endless tasks! How much better it were to be an unknown man, if I am never to cease from military service, and cannot lay aside this load of envy and spend my time in the country with my wife!”

This was all for show, of course. Any close friend of Pompey understood that this was, basically, his dream job. And, certainly, Pompey wasted no time in raising an army and marching east towards Anatolia. He stopped at every kingdom and province along the way, not only to continue building his forces but also to undo everything Lucullus had done. He rewarded those that Lucullus had punished and punished those that he had favored, if nothing else, then to show everyone that Lucullus was now as weak as a newborn lamb and that Pompey was the new head honcho. There wasn’t much that Lucullus could do about it, but he did insult Pompey by comparing him to a lazy carrion bird who feasted on the bodies that others had killed, referring here to the fact that he always joined wars towards the end, after other men such as Crassus, Metellus, and Catulus did the work.

It’s an interesting idea and might be a valid criticism. It’s also what definitely happened in this case. By the time Pompey made his appearance in 65 BC, the Kingdom of Pontus was mainly under Roman control and the fighting was taking place in its neighboring allied kingdoms such as Armenia, Colchis, and Iberia.

Pompey started his campaign by fighting Mithridates at the Battle of the Lycus in Ionia. It was a decisive victory for Pompey and he forced his opponent to fall back and retreat into the mountains. Mithridates was hoping that his allies would keep Pompey busy while he raised a new army, but he was wrong on both counts. His allies proved no match for the Roman might. A few more battles occurred in 65 BC, all won by Pompey, and the victory at the Battle of the Abas against the Kingdom of Albania turned out to be the last open engagement of the campaign.

Meanwhile, Mithridates was not successful in reinforcing his army. It seems that the local forces had been all but exhausted and those who remained were fed up with years and years of war. Even the king’s own sons rebelled against their father so, with no other prospects, Mithridates VI committed suicide in 63 BC. Half of the kingdom of Pontus was annexed by Rome and, together with Bithynia, was turned into a new Roman province.

Pompey had won the Mithridatic War, but he wasn’t finished. Since he was already in the area and still had an army itching for a fight, why not put it to good use? He captured Syria, turning it into another Roman province. He also attacked Judea, annexing half of it and rendering the other half into a powerless, vassal state. He then “liberated” hundreds of small towns, settlements, and strongholds and completely reorganized Rome’s eastern defensive frontier into a new system that stayed in place for hundreds of years.

Pompey had no authority to do any of this, by the way. Officially, his reasoning was that the region was unstable and that this was a threat to Rome’s new eastern possessions, but many feared that he had completely given into his insatiable lust for power and glory and that, soon after, Rome would be next.

Pompey Plays Politics

The entire Senate collectively breathed a sigh of relief in December 62 BC, when they found out that Pompey had reached Brundisium in southern Italy and had disbanded his army. He paid his soldiers, sent them on their merry way, and went on a sort of celebration tour throughout Italy. Suffice to say that he expected another triumph when he reached Rome. His actions against the pirates and against Mithridates were more than enough to warrant such festivities, but this was the biggest triumph in the history of Rome. Cassius Dio referred to it as the “great event” and said that Pompey had a trophy for every single war he won, and then a giant one “decked out in costly fashion and bearing an inscription stating that it was a trophy of the inhabited world.”

Plutarch gave a more detailed account that truly highlighted the extent of Pompey’s conquests. He said:

“His triumph had such a magnitude that, although it was distributed over two days, still the time would not suffice… Inscriptions borne in advance of the procession indicated the nations over which he triumphed. These were: Pontus, Armenia, Cappadocia, Paphlagonia, Media, Colchis, Iberia, Albania, Syria, Cilicia, Mesopotamia, Phoenicia and Palestine, Judaea, Arabia, and all the power of the pirates… Among these peoples, no less than a thousand strongholds had been captured, and cities not much under nine hundred in number, besides eight hundred piratical ships, while thirty-nine cities had been founded…”

To put it simply, Rome had never seen a champion the likes of Pompey the Great. In spite of this (or, more likely, because of this), Pompey didn’t wield a lot of political influence. He wanted the Senate to ratify and recognize all the cities, vassal states, and kings that he installed in the east, but they were reluctant to do so. Many Senators had been wary for years of all the power granted to Pompey, so they thought it best to cut him down to size a bit.

Not much Pompey could do about it. He was at home on the battlefield, not in the senate house. He knew he didn’t have the political muscle to take on his detractors, but that would soon change. Around 60 BC, a powerful alliance was formed – the First Triumvirate – an informal coalition between three of Rome’s wealthiest, most influential, and most popular figures – Pompey, Marcus Crassus, and Julius Caesar. The goal was for each one to support the interests of the other two, but it’s pretty clear that Caesar got the most out of their little entente. First, he was given the consulship in 59 BC, then he was made a governor, and, finally, sent to fight in the Gallic Wars.

On his end, the triumvirate enabled Pompey to get his eastern settlements ratified and land grants provided for his veterans. He was also appointed consul again in 55 BC and enjoyed a five-year stint as praefectus annonae, an important position that placed him in charge of the grain supply to Rome.

Despite its effectiveness, from the beginning, the alliance was tenuous, at best. Pompey and Crassus never truly liked each other. Pompey and Caesar grew closer when the former married the latter’s daughter, Julia. However, she died during childbirth in 54 BC, and the relationship between Pompey and Caesar turned decidedly frostier from then on. The following year, the triumvirate officially ended after Crassus died at the Battle of Carrhae against the Parthian Empire. And then…a war erupted that changed the course of history forever.

Pompey Vs Caesar

We’re not going to go into a massive preamble about the start of the civil war. That has more to do with Caesar than with Pompey, and we already have a bio on him if you want the story in full. Suffice to say that, in 49 BC, Caesar crossed the Rubicon. After winning the Gallic Wars, he refused a demand from the Senate to disband his troops and marched into Italy with an army. From that point on, civil war became inevitable.

All those years, the Senate feared that this was something that Pompey would do, although he never did. And now that Caesar had done it, they rushed to Pompey for help. He agreed, but was caught off guard by the rapid pace at which Caesar advanced toward Rome. When the two sides first met in battle at the Siege of Brundisium, an outmanned and ill-prepared Pompey suffered one of his greatest defeats.

This gave Pompey the dark realization that he could not defend Rome, so he abandoned the city and fled to Macedonia to properly mobilize his forces. He set up his camp in the city of Dyrrhachium, in modern-day Albania. Caesar besieged the city in 48 BC, but after months of inconclusive skirmishes, he conceded defeat and made a strategic retreat, thus tying their score one-all.

The great decider occurred in August of that year, at the Battle of Pharsalus in central Greece. Pompey didn’t want to do it. He thought he was rushing things, but his allies all pressured him to meet up with a confederate named Metellus Scipio and take out Caesar.

That’s not how things went down. Pompey’s plan was to make use of his large cavalry, attack Caesar’s right wing from the flank, go around the rear of the enemy, and trap them between two armies. However, Caesar shrewdly guessed Pompey’s strategy and reinforced his right wing, but kept his extra soldiers out of sight until it was too late for Pompey’s men. They pounced at the right time and brought chaos, confusion, and death to Pompey’s cavalry units, which retreated in a panic, and, from that moment on, the battle was as good as lost.

It was, undoubtedly, Pompey’s greatest defeat. He escaped the battlefield disguised as a civilian and fled to Egypt, thinking that the Ptolemies were friendly and would help him rebuild his army. But they had already chosen their side. On September 28, 48 BC, just one day short of his 58th birthday, Pompey disembarked at Alexandria and was immediately waylaid by assassins who stabbed him to death right on the dock. They cut off his head and threw his body into the ocean. A freedman loyal to Pompey fished out his corpse and gave him a modest funeral.

Caesar himself was appalled by this act, and “burst into tears” when he was presented with Pompey’s head and seal ring. He demanded Pompey’s assassins and had them put to death. It was an ignominious end to one of history’s greatest military careers.