Julius Caesar, Spartacus, Sulla, Marcus Crassus – all these men have had a tremendous impact on the history of Rome and we have done bios on all of them. And each time, we mentioned another man who, in turn, had a great influence on their own lives and careers – Pompey.

He was, arguably, the most successful military leader that Rome had ever known and today we are giving him his due. It is time for the man himself to take center stage in a special, extended two-part bio as we look at the life and career of Pompey the Great.

Early Years

Pompey was born Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus on September 29, 106 BC, in the region of Picenum. He was part of a family that was in the midst of a quick climb up Rome’s social ladder. Just a few decades earlier, the name gens Pompeia would have meant nothing to the average Roman. They were, after all, plebeians, meaning that they were free Romans, but not part of the elite patrician class…basically, commoners. But in 141 BC, a man named Quintus Pompeius became the first family member to receive a consulship. This opened the door for other Pompeians to attain important political offices, as well as fill up the family coffers. Consequently, by the time Pompey was born, his father, Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, was among the richest men in Picenum.

That being said, it appears that Strabo was not a popular man. Quite the opposite in fact. Plutarch noted that, when Strabo died, seemingly after being struck by a thunderbolt, people took his body from the funeral pyre and dragged it through the streets while throwing stones and hurling insults at it. So, yeah, not exactly a man of the people, which put him in stark contrast with Pompey. In fact, the same Plutarch mentions that never in Roman history had there ever been a bigger gulf between father and son in terms of how much the people hated one and loved the other. The historian simply fawns over Pompey as if he were the president of his fan club. Here’s what he says:

“…no Roman ever enjoyed heartier goodwill on the part of his countrymen, or one which began sooner, or reached a greater height in his prosperity, or remained more constant in his adversity, than Pompey did…there were many reasons for the love bestowed on Pompey; his modest and temperate way of living, his training in the arts of war, his persuasive speech, his trustworthy character, and his tact in meeting people, so that no man asked a favor with less offense, or bestowed one with a better mien. For, in addition to his other graces, he had the art of giving without arrogance, and of receiving without loss of dignity.”

That’s just one paragraph. There’s more, but we don’t have time for the whole love fest. Suffice to say that Pompey was popular with the people.

We probably mentioned this before, but it’s worth repeating. Barring extraordinary examples (such as today’s subject), the Romans had a pretty standard sequence for the men of the upper classes to advance their careers. It was called the cursus honorum and it started with the office of quaestor and, ideally, ended with the position of consul. Before that, though, it was expected of the men to serve in the military, so that was Pompey’s first stop. He joined his father’s command around 90 BC and fought in the Social War.

This was not one of Rome’s more famous conflicts, but it was an important one nonetheless because it led to the complete Romanization of Italy. Basically, back then, Rome was the dominant power in Italy, but it didn’t control all of it yet. It had multiple allies in the region known as socii, but they were unhappy that they weren’t granted the same rights as citizens of Rome, so in 91 BC they went to war. The fighting went on for four years and, even though Rome won, the socii ultimately got what they wanted as they were granted Roman citizenship in order to avoid similar conflicts in the future.

Strabo obtained his biggest moment of glory at the Battle of Asculum in 89 BC. For this, he was celebrated on the streets of Rome with a triumph and was named consul for that year. As far as Pompey was concerned, it was a bit too early for him to shine as a soldier. However, in 87 BC, once his father died and he inherited the family estate, that became a different matter entirely. Pompey didn’t have to wait too long to put his burgeoning military prowess to good use because, in 84 BC, Rome become embroiled in its fiercest power struggle yet known as Sulla’s civil war.

Pompey and the Civil War

Now, we’ve already talked about Sulla here on Biographics so, if you want the full picture of that conflict, you can give that video a quick watch. Basically, Rome was in the grips of a civil war between two factions – one led by Sulla and the other by Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Cinna. Pretty early into the war, it became evident that this wasn’t the kind of conflict where other Romans could just stick their heads in the sand and wait for it to blow over. Everyone had to choose a side, or it would be chosen for them.

For Pompey, the decision was fairly easy since he bore a grudge against Cinna. Referring back to good ol’ Plutarch again, the historian said that young Pompey escaped an assassination attempt engineered by Cinna while campaigning with his father, after Cinna supposedly bribed a man named Lucius Terentius to stab Pompey while he was sleeping in his tent.

Given that Gaius Marius died early on during the civil war and Cinna became the leader of his faction, it’s no surprise that Pompey decided to throw his lot in with Sulla. But he almost didn’t get the chance to do it as he nearly lost everything at the outset of the war. When the Marius/Cinna faction took over Rome, they began enacting proscriptions. Those who were found guilty were declared outlaws, had their properties confiscated, and most were also executed, for good measure. At first, they did this solely to supporters of Sulla, but they generously expanded their program to include many other Romans whose wealth they coveted.

And Pompey soon counted himself among those wretched souls, accused of stealing some of the booty from the Battle of Asculum. If he would be found guilty, his property would be confiscated and he would be lucky to escape with his life. But that’s not what happened. Instead, he managed to prove that a freedman in his father’s employ was the true booty thief. That, plus his natural charms managed to sway the magistrates who found him innocent. He even married the judge’s daughter, Antistia, his first of five wives.

Realistically, Pompey probably escaped with his life and his wealth intact because his enemies didn’t perceive the young, inexperienced soldier as a threat. Even so, Pompey knew not to tempt fate, so he quickly left Rome and retreated to Picenum. There, he seemingly fell off the grid for the next few years, but what Pompey was really doing was quietly recruiting troops and waiting for the right time to strike.

That time came in 83 BC when Sulla and his army began marching on Rome. This was the point of no return for Pompey. Once he aligned himself with Sulla, he intertwined their fates. Either both men ended up rich and powerful beyond their wildest dreams or…they both got their heads chopped off and mounted on poles. Both options were good, but Pompey probably leaned towards the first one. It’s not like he was the only one taking this gamble. Another name you probably recognize, Marcus Crassus, also allied himself with Sulla, as did another influential Roman general named Metellus Pius.

Without a doubt, Pompey was the youngest and least experienced in that group, but he had two things going for him. First, he had the money to equip and train all of his troops. And second, he was just so damn likable and charismatic. You’d think this might not matter so much. This was, after all, war and not a talent show competition, but the reality was that both sides were in full-on recruitment mode, and every man Pompey enticed to his side meant fewer soldiers fighting for his enemies. It is said that Pompey started out with only one legion when he left Picenum but had amassed three legions by the time he actually entered battle.

Speaking of which, let’s get to the fighting. Like Gaius Marius, Cinna had also died by this point, and a guy named Carbo was running the show. Before joining up with Sulla, Pompey scored three quick and surprising victories against three of Carbo’s generals. When Sulla heard of this, he raced to meet this young upstart, and, when the two finally met, Pompey hailed Sulla as “Imperator.” In return, Sulla got off his horse, took off his helmet, and returned the same greeting. This was a massive show of respect on behalf of the experienced veteran Sulla, who, more or less, made it clear to everyone that the 23-year-old Pompey was now his protégé.

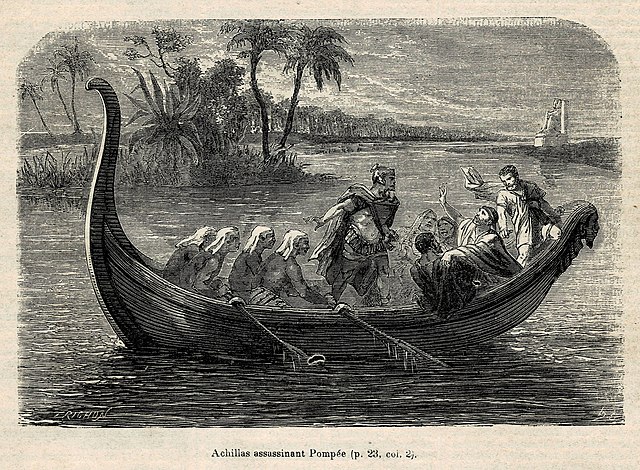

To be fair, Pompey paid off this trust in spades. After his meeting with Sulla, he left for Gaul, where he provided reinforcements for Metellus. He wasn’t present at the decisive Battle of the Colline Gate, which won Sulla the civil war, but he was then tasked by Sulla with chasing down the remaining opposition, so they would not be able to raise new armies and reignite the conflict. This included Carbo himself, who abandoned Rome once he knew the war was lost. He intended to retreat to Africa to gather new troops but only made it as far as Sicily before Pompey caught up to him, captured him, and had him executed. Pompey then crossed the Mediterranean into Africa and was successful in crushing the last remnants of the Marius/Cinna faction at the Battle of Utica in 81 BC. Once his task was complete, it was time for Pompey to go back to Rome and enjoy his spoils of war.

Pompeius Magnus

The streets of Rome were flooded with cheers and exaltations as Pompey made his triumphant return. Not to be outdone by the common rabble, Sulla greeted his protégé with the name Pompeius Magnus – Pompey the Great, the title that he would use from then on. Sulla also arranged for the young general to divorce his first wife and marry his step-daughter, Aemilia, who died during a miscarriage less than a year later.

And, of course, along with the respect and power, Pompey was also granted untold wealth. Like Marius and Cinna before him, Sulla enacted proscriptions on his political enemies and allowed his closest allies to do pretty much whatever they wanted in order to enrich themselves.

It didn’t take long for all the success to go to Pompey’s head. He was still in his mid-20s and already one of the richest and most powerful men in Rome, and he felt like showing off. Nowadays, he’d probably post pictures of himself in his private jet on social media, but Pompey wanted the 1st-century version of an Insta-brag – a triumph through the city streets.

Sulla balked at the idea. Nobody as young as Pompey had ever celebrated such an honor. According to Roman law, only a consul or a praetor might receive a triumph, and Pompey, “who had scarcely grown a beard as yet,” wasn’t old enough to even become a senator. But hey, Sulla initiated a civil war and declared himself dictator, so who was he to give lectures on Roman traditions?

Despite many protestations from other officials, Sulla relented and Pompey was given his triumph. But his little vanity project didn’t exactly go according to plan. Instead of having his chariot pulled by horses through the streets, Pompey wanted to have it drawn by four elephants that he brought back from Africa. Except that he didn’t realize that the elephants would be too wide to fit through the city gates. So right at the beginning of the triumph, the procession had to stop outside Rome and have the elephants swapped with horses, all while Pompey sat in his chariot, waving at everyone like an idiot and pretending that nothing was wrong.

But despite occasional missteps, Pompey’s reputation flourished. If there was one thing that could endear someone to all the classes of Rome, it was military glory and, so far, Pompey had a spotless record. But his meteoric rise rubbed some people the wrong way, including Sulla who began resenting his young disciple. Tensions between the two increased over a man named Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. Sulla hated him and called him “the worst of men.” Pompey, for whatever reason, not only liked him but publicly campaigned for Lepidus to be appointed consul.

The deterioration of the relationship between mentor and protégé became evident after Sulla’s death in 78 BC because he completely snubbed Pompey in his will, even though he bequeathed gifts to his other friends. Furthermore, Sulla delivered a final “I told you so!” from beyond the grave because, that same year, Lepidus was named consul and then tried to stage his own rebellion and take power by force. He was joined by Cinna the younger, the son of the man who fought against Sulla, as well as Marcus Junius Brutus, the father of Caesar’s future assassin. In fact, Lepidus also asked a young, up-and-coming Julius Caesar to join his uprising, but he wisely decided to stay out of this one. Probably civil wars just weren’t his thing.

Anyway, Lepidus’s main rival was a man named Catulus, the other consul. It’s worth reminding everyone that the Roman Republic always had two consuls at the same time so that no one man could gain absolute power, although it certainly didn’t stop them from trying. But Catulus wasn’t exactly praised for his unparalleled military genius, so the Senate was hoping that Pompey might lend a hand, as well. And fortunately for them, he did. Despite his previously ardent support of Lepidus, Pompey did his mea culpa and rallied against him. He was sent to Mutina, in Gaul, which was Lepidus’s neck of the woods, to lay siege on Brutus. That way, assuming Catulus would also be victorious, Lepidus would be left with nowhere to retreat and regroup.

Pompey’s siege was lengthy but successful, and upon capturing Brutus he swiftly had him executed, even though the latter had surrendered. This wasn’t the first time that Pompey had one of his opponents killed under…let’s call them “iffy” circumstances. Carbo had suffered the same fate and his death earned Pompey the ignominious moniker of adulescentulus carnifex – “the teenage butcher.”

Meanwhile, Catulus also achieved his goal and defeated Lepidus at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, although his victory wasn’t decisive enough to completely negate Lepidus as a threat. Once again, Pompey was “the closer” who was sent in to obtain a more permanent result, which he got…sort of. He defeated Lepidus in battle, but the latter was still able to escape and flee to Sardinia, where he fell ill and died so…mission accomplished?

Pompey and the Sertorian War

Already, Pompey had amassed an impressive military resume. Many other commanders would have used all of that stockpiled glory to parlay it into a safe, cushy position as a senator, governor, maybe even a consul. In fact, that’s exactly what Catulus was hoping Pompey would do. Given the last decade or so, where Rome saw conflict after conflict right outside its city gates, any military leader with command of a loyal army was cause for concern. After all, who knows what ideas Pompey might get? That’s why Catulus told him to pay his soldiers, disband his army, and return to Rome where he could be properly feasted for his victory.

As it turned out, Catulus was right to be concerned because Pompey did not want to disband his army. It appears that glory in battle tasted much sweeter to him than even the most sumptuous Roman banquet, but, at the same time, he wasn’t so gung-ho that he was willing to make an enemy of the Senate. So he searched for a compromise by seeking out another conflict where his services might be needed and he found it in the Iberian Peninsula, or Hispania, as the Romans called it.

That region was under the hegemony of a general named Quintus Sertorius. A former ally of Cinna and Marius, Sertorius packed up his bags and retreated to Hispania when his side lost the civil war. There, he found allies in some of the local Iberian tribes and made himself the de facto ruler of the peninsula. Ever since then, Rome had been trying to retake control of the region but failed to do so. Granted, it didn’t allocate a lot of resources to the problem since Lepidus was a more pressing issue, but Sertorius also proved himself quite adept at doing a lot with a little. Since he was usually outmanned and outgunned, he often resorted to guerilla warfare to disable his enemies and prevent a pitched battle from happening. This strategy worked for years. In fact, when Pompey got in on the action, Sertorius was already successfully foiling Pompey’s former military ally, Metellus Pius.

The legality of Pompey’s actions was, again, iffy, since he disobeyed an order from Catulus and kept coming up with excuses to not disband his army. He was relying on his supporters in the Senate, particularly a senator named Lucius Philippus, as well as others who realized that they needed Pompey, regardless of their feelings towards him. Philippus even suggested that Pompey be given the authority of a proconsul, referring to a military or administrative leader who was given powers outside of a regular term. Traditionally, only men who had previously served as consuls could be made proconsuls. Pompey, meanwhile, had never even held the position of quaestor, the first stop on the cursus honorum. However, as we saw with his military triumph (his first military triumph, we should specify), Pompey was an extraordinary man, one for whom the standard rules simply did not apply.

Pompey arrived in Hispania in the spring of 76 BC. This would be his home for the next five years as Sertorius would prove to be his biggest challenge yet. In fact, Pompey started off his part in the Sertorian War, as it was known, with a very inauspicious and rare event – a defeat in battle at the Siege of Lauron. And it wasn’t due to being outnumbered or some natural disaster, either. On that day, Sertorius was simply the better general. He allowed his opponent to think he had the upper hand when, in fact, he was falling for an ambush. The young, cocky Pompey realized too late that his men were marching into a trap, and, by that point, there was nothing he could do but watch up to ten thousand of his soldiers get slaughtered by Sertorius’s forces.

This shocking outcome left Pompey reeling. Some of the shine came off the “golden boy” who, up until that point, seemed like he could do no wrong, but he made a comeback the following year. Sertorius’s mistake was thinking that Pompey was a beaten man. He left him to his underlings while Sertorius himself went to deal with Metellus. But the Pompey of old returned at the Battle of Valentia, in 75 BC, and he not only defeated Sertorius’s generals but also inflicted massive losses on their armies, thus compensating for his shameful performance at Lauron.

The next time he fought Sertorius was at the Battle of Sucro, and then the Battle of Saguntum that same year. Both ended in stalemates. Afterward, Sertorius decided to retreat into the mountains, regroup his forces and resume his guerilla tactics by attacking supply lines and scouting parties.

At the same time, Pompey’s side was starting to run thin on troops and resources, so he sent word to Rome to ask for money, supplies, and reinforcements. Since both camps were in rebuilding mode, the next few years were pretty quiet, with only the occasional skirmish breaking up the monotony. This was fine for Pompey, but Sertorius was dealing with in-house problems – low morale, defections, conflicts between Romans and Iberians, all spurred on by one of his generals, Marcus Perperna, who coveted the top spot for himself.

Ultimately, it was treachery and hubris that ended the Sertorian War. Perperna and his co-conspirators assassinated Sertorius at a feast in 73 BC, a mistake that would shortly bring on their own demise. For whatever reason, Perperna assumed that things would magically get better with him in charge, but it was quite the opposite since Perperna was destined to be Robin to Sertorius’s Batman. He didn’t have the charisma, experience, or skill to be an effective leader. Many of his troops abandoned him, either defecting to the other side or simply going home.

When Metellus heard that Sertorius was dead, he was confident that Pompey could handle the remnants of his army, so he returned to Rome. The latter, indeed, proved up to the task, using a simple decoy tactic to lure Perperna’s troops into the open and then crushing them in an ambush. Perperna and most of his officers were captured and summarily executed, as per Pompey’s regular modus operandi. He still had to spend some time taking care of stragglers, but Pompey had won the Sertorian War. He was getting ready to return to Rome where he, undoubtedly, would enjoy another triumph, when he received word that an escaped gladiator was causing chaos throughout Italy. Not one to pass up a good fight, Pompey had found his next opponent…Spartacus. But we’ll talk about that next time when we pick up the story in Part II: The Wrath of Pompey.