Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the scourge of the Western World was polio. Every summer, it seemed, it attacked at random, sickening thousands across the United States and Europe. The ones it didn’t kill outright, it often left crippled, destroying the body’s ability to control limbs and confining victims to wheelchairs and crutches for life. The worst affected were unable to breathe without assistance from mechanical devices. Worst of all, the disease mostly attacked young children, making polio a parent’s worst nightmare, since it struck without warning and it had no cure.

Polio had an outsized impact on Western society in the 20th century, the fight against it causing improvements to medical science, philanthropy, disability rights, and the responsibility of government to protect its citizens from deadly pathogens. Today, the virus is almost nonexistent in the wild, a result of a concerted effort to eradicate this pestilence from humanity once and for all. But the effect it has had on our world is likely to never be forgotten.

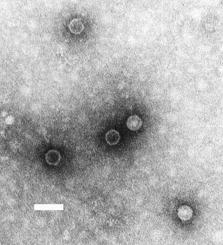

The Virus

The poliovirus was first observed in 1909, and is the pathogen that causes poliomyelitis, typically shortened to just “polio”. The virus primarily lives in a person’s digestive system, especially the large intestine, and when it remains there, it is completely harmless. 95% of people infected with poliovirus have no symptoms at all. In 5% of cases, however, the disease “escapes” from the digestive system and infects other parts of the body, particularly the central nervous system. Once there, the virus can interfere with the nervous system’s ability to control muscles, such as the ones needed to move your legs. Initially this is felt as simply muscle weakness, but can progress to partial or complete paralysis as nerves are damaged or destroyed. In many cases, the destruction is irreversible, and in the most severe cases, can cause the loss of ability to control the diaphragm, which is the muscle responsible for ensuring your lungs function properly. This can cause the death of the victim unless they are put onto artificial breathing equipment.

Origins of the Disease

Polio has been observed throughout human history. Egyptian paintings depict healthy people with withered limbs and children walking with canes, thought to be representative of a polio infection. It is believed that the Roman Emperor Claudius walked with a limp caused by polio. The Scottish author, Sir Walter Scott, is one of the first people to be confirmed to have suffered a bout of polio as a child, as the science of disease was better understood at the end of the 1700s. Continued study of the disease occurred throughout the 19th century, and eventually it was christened “infantile paralysis” because of who it affected and what it did.

Still, in all that time, the illness was a small-scale problem. It was endemic, sure, but it didn’t rise to the level of epidemics such as those caused by smallpox, yellow fever, or cholera. But something changed in the latter half of the 19th century to bring polio out into the open. The Industrial Revolution was in full swing, causing people to move from rural areas to urban ones. Cities became overcrowded and poorly managed, as the explosion in population rapidly exceeded the capacity of existing infrastructure to handle them. People lived packed together in squalid tenements, malnutrition was rampant, and the sanitation systems, particularly the sewers, were overwhelmed.

People infected with poliovirus shed it in their fecal matter, the virus can stay active for up to a week after leaving the body in this way. When human waste is being dumped into the same water sources that drinking water is being drawn from, people can become infected with the virus from drinking contaminated water. Once a sufficient number of people are infected in this way, the virus can transmit itself from person to person through coming into contact with infected saliva, such as when standing close to a person who is talking to you.

It is believed that in this way, virtually the entire population of the United States and Western Europe became infected with poliovirus by the end of the 19th century, and the terrifying epidemics began soon after.

The Polio Pandemic

In 1916, polio struck the United States with a previously unseen fury. The epidemic centered on New York City, which saw 9,000 cases, over 2,000 of which were fatal. Nationwide, there were over 27,000 afflicted and 6,000 deaths. The epidemic caused widespread panic in New York, as public spaces were shut down and residents fled the city for the countryside. Families with polio victims were quarantined, and were even publicly identified in local newspapers. By that winter, the disease had subsided, but it proved to be the start of a pattern.

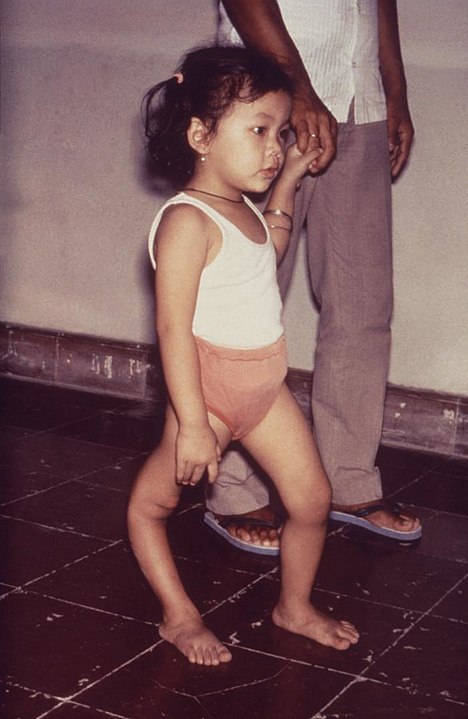

Every summer, polio emerged from its winter slumber to plague the populations of the United States and Western Europe. Epidemics broke out all over the place, with little warning. Two thirds of those afflicted were children between the ages of 5 to 9, leading it to become America’s most feared disease in the first half of the 20th century.

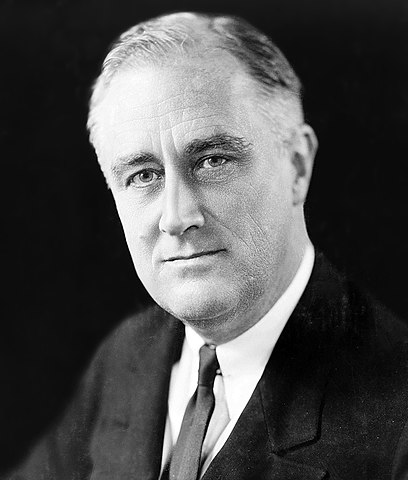

The disease also affected adults, though it was less common. In 1921, Franklin D. Roosevelt was a rising star in the Democratic Party, having been the party’s Vice-Presidential candidate in the 1920 election. The former Assistant Secretary of the Navy had returned to New York City after the Democrats lost the election to Warren G. Harding, and ran his own law firm, biding his time until a new political opportunity came up. But while on vacation with his family Roosevelt was struck down by illness, eventually becoming completely paralyzed from the waist down.

At the time, Roosevelt was diagnosed with polio, but many doctors today argue that his symptoms more closely resemble Guillain-Barre Syndrome, an auto-immune disease. But for the purposes of this story, it doesn’t really matter, as Roosevelt became personally identified with polio for the rest of his life and helped lead the fight against the disease until his death in 1945.

Battling Polio

FDR tried many different treatments to try and recover the ability to walk after his illness. In 1924, he visited a natural spring in Warm Springs, Georgia, believing hydrotherapy would help with his disability. It didn’t, not really, but in 1927, he bought the place and turned it into a rehabilitation center for polio victims, representing the first concentrated effort to combat the effects of polio.

Roosevelt, of course, would stage one of the most remarkable political comebacks in American history, being elected Governor of New York and then, in 1932, President of the United States. He took careful measures to ensure that his disability was not widely known to the public. He gave speeches while wearing heavy braces that could be locked into place, allowing him to stand. He made a rough imitation of walking by jutting his hips back and forth, lifting his legs in the process. And he never allowed himself to be photographed or filmed while in his wheelchair. Still, he never forgot where he had come from, and continued to develop his rehabilitation center in Warm Springs. He turned to his friend, Basil O’Connor, to establish the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis in 1938.

To raise money for the foundation, O’Connor established a new approach: instead of only targeting wealthy patrons for large donations, he would ask the general public to donate small amounts. The campaign particularly invited children to send in ten-cent coins. The “March of Dimes” campaign was incredibly successful, the White House received tens of thousands of letters with dimes in them, many donated from children who wanted their schoolmates to get well, raising millions of dollars in the process. The March of Dimes soon became shorthand for the name of the foundation itself, and is credited with being one of the first “crowd funded” charitable giving campaigns. Roosevelt became so synonymous with the March of Dimes that, after he died in office in 1945, a new dime was issued the next year with his face on it, a design that continues to this day.

March of Dimes used their donations to fund specialized treatment centers for polio patients, helping families pay for the costs of treatment and for necessary equipment, such as iron lungs, which were artificial breathing devices for victims whose diaphragms weren’t working anymore. By the 1950s, over 80% of polio victims nationwide were receiving funding from March of Dimes. They also poured millions of dollars into research efforts to develop a polio vaccine, which would stop the disease once and for all.

The Race for a Vaccine

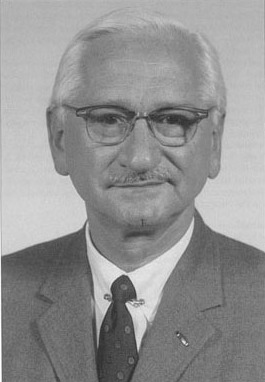

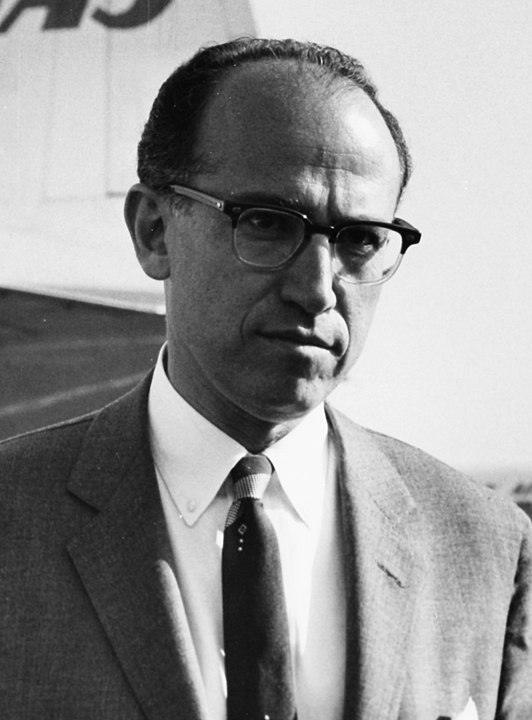

Dr. Jonas Salk had worked very hard to get where he was in life. The son of an immigrant Jewish family from New York City, Salk had gotten through his undergraduate program at CCNY and medical school at NYU largely thanks to his own brilliance and hard work. He had faced discrimination and economic hardship but became a doctor anyway. But Salk did not want to practice medicine. His heart lay with medical research, the science of how disease affected the human body and how it could be prevented.

In 1947, Salk was running a small research laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh when the March of Dimes approached him. They needed help studying the poliovirus, and offered funding to hire more researchers and to enlarge his lab, with better equipment. Salk accepted.

At this time, polio epidemics were getting worse in the United States. In 1949, 42,000 cases were reported in the US, causing over 2,000 deaths. The 1952 outbreak was the worst: 58,000 confirmed cases, of which 3,000 died and almost 22,000 were left in some form of paralysis. The American public was almost hysterical, terrified that their children would be the next to be afflicted. Basil O’Connor, the head of the March of Dimes, knew that this had to be stopped.

In 1951, O’Connor met Salk for the first time. Salk had an innovative idea for a vaccine he wanted the March of Dimes to help him with. At the time, so-called “live virus vaccines” were medical standard. A live virus vaccine, also called an attenuated vaccine, takes a virus and changes it so that it is less virulent, thus inoculating the body against the wild virus by introducing it in a safer form so the immune system can produce antibodies against it. This is an effective way to make a vaccine, but it takes time, a long time, to perfect. Dr. Albert Sabin, working at his lab at the Children Hospital in Cincinnati, was leading the effort to make a live vaccine for polio. He brushed off O’Connor’s attempts to speak up his progress, seemingly indifferent to the fact that children were getting sick and dying waiting for his work to be finished.

Salk, on the other hand, proposed using an inactivated virus vaccine. Also called a dead virus vaccine, an inactivated virus vaccine uses a virus that has been killed, tricking the body into producing antibodies against it. This could be mass produced much faster than a live virus vaccine. Salk had first used this formula while working on an influenza vaccine for the US Army during World War II, and believed it would work for polio as well. Sabin and other medical researchers called Salk’s theory “junk science,” but O’Connor believed in anything that would get a vaccine to the public as soon as possible, and agreed to fund Salk’s research.

The Salk Trials

Salk and his team in Pittsburgh worked tirelessly. They achieved a breakthrough late in 1952, when a vaccine they had developed worked in a test on laboratory animals. The next step was human trials. In early 1953, Salk tested his vaccine on a group of children and adults, including his own family and himself. No one got polio. More human trials were conducted throughout 1953, with similar results.

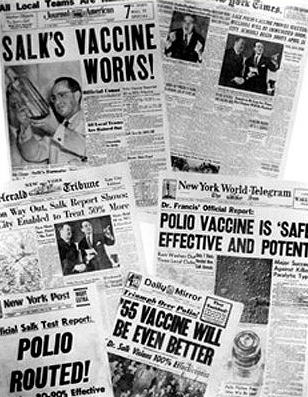

Now, O’Connor and Salk were ready to conduct a large-scale human trial. Funded by the March of Dimes, the Francis Field Trial began in 1954. Dr. Thomas Francis of the University of Michigan, Salk’s mentor, ran the trial with a staff of over 100. The year-long trial ultimately involved more than 1.8 million schoolchildren across the United States, the largest human medical experiment in American history. The world waited for the results with bated breath. On April 12th, 1955, the nation’s press gathered at Rackham Auditorium at the University of Michigan to hear the results of the field trial. The date was particularly significant: it was the 10th anniversary of the death of President Roosevelt. Salk, Francis, and O’Connor informed the world that their vaccine worked, that it was safe, and that they would start mass producing it for use immediately.

The news touched off widespread celebration across the country and the world. It was the culmination of almost 20 years of work from the March of Dimes, who had raised millions of dollars from millions of ordinary Americans, all in the hope of seeing this disease stopped. Medicine had the tools, now it was time to stop the bug once and for all.

Vaccinating the World

The effort to inoculate against polio was one of the largest vaccination efforts in human history. In the United States, new government regulations and oversight organizations needed to be created to control the quality of the manufactured vaccine doses, to certify them as safe, and to create records of who had been vaccinated. Being vaccinated against polio became a requirement to attend public school, but few parents needed to be coerced into getting their children vaccinated, they clamored for the chance to protect their children from the dreaded disease.

A scandal erupted in 1955 when a bad batch of the polio vaccine manufactured by Cutter Laboratories actually infected hundreds of school children with the live polio vaccine instead of the safe version. This incident brought attention to the fact that the federal government actually had little oversight of vaccine production in place, and sought to rectify this immediately, giving the Food and Drug Administration the power to regulate vaccine formulas for quality and safety, a practice that continues to this day and gives the American consumer trust that the vaccines they are being given are safe. It didn’t take long before the polio vaccine was being produced in large quantities and the safety of the product was never questioned again.

The March of Dimes and the United States government jointly promoted the vaccination campaign, and cases of polio began to drop precipitously. In 1952, there were 58,000 cases in the United States. In 1957, there were 5,600. By 1961, the US only recorded 161 cases. That same year, Albert Sabin’s live virus vaccine was ready to use. It was an oral vaccine, as opposed to Salk’s, which was an injection, and it was cheaper than Salk’s as well. Sabin’s vaccine eventually replaced Salk’s as the most commonly administered vaccine worldwide. But both doctors were hailed as heroes, and they both received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian decoration. Most amazing of all, perhaps, is that no one, not Salk, Sabin, O’Connor, or anyone else, made any attempt to patent their vaccine, which would have been worth billions of dollars to a patent holder. All of them said that this was for the public benefit and that they shouldn’t therefore profit off of it. This allowed the vaccines to quickly make their way around the world.

Dealing with the Aftermath

After 15 years, America wasn’t afraid of polio anymore. The disease had been all but conquered, and most of America had moved on. But for the hundreds of thousands of people who had survived polio and been partially or totally disabled as a result, the vaccine did nothing to help them. After months or years spent in the hospital, they came home to discover they now lived in a world that was seemingly designed to make their lives more difficult.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, there were few, if any, protections for disabled people enshrined into law. Schools, businesses, and other public places were almost never wheelchair accessible, and few able bodied people wanted to be bothered with them. Often they ended up shipped off to special schools “for crippled children” where they could be hidden out of sight and out of mind.

As a new generation of children affected by polio grew to adulthood, they began to become more politically active. They were one of the largest disability groups in the country, and they were in the forefront of the disability rights movement that fought as part of the wider Civil Rights Movement for equal access and equal treatment in society. This culminated in the passing of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990, mandating public accommodations for people with disabilities wherever possible. Although there are relatively few polio survivors still alive today, all the progress that has been made in the rights of the disabled couldn’t have been accomplished without their leadership.

Ridding the World of Polio

In the United States and in most of the countries of Europe, the number of cases of polio dwindled down to zero throughout the 1970s and ‘80s. The vaccination programs in these countries were so successful in stamping out the disease, that the World Health Organization began to believe that complete eradication of polio was not only possible, but something that they could accomplish. After smallpox was declared eradicated in 1980, the WHO began to turn their attention more seriously to taking down polio.

By 1988, there were an estimated 350,000 cases of paralytic polio worldwide, mostly occurring in poor countries with little access to modern medicine and undeveloped sanitation facilities. The WHO announced a partnership with UNICEF and Rotary International to launch the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, with the goal of eradicating polio worldwide by the year 2000. The GPEI aims to vaccinate every person in countries where polio is still endemic.

The initiative failed to completely eradicate the disease by the year 2000, but they had made terrific progress. 575 million children were vaccinated through the campaign, almost a tenth of the world’s population. From 350,000 estimated cases in 1988, the WHO recorded less than a thousand cases in the year 2000. Five years later, with increased funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, polio was considered endemic in only four countries: India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Nigeria.

Sweeping the disease out of these final places of refuge ran into unexpected challenges. Inadequate health care infrastructure poses an obstacle in getting everyone vaccinated, and that’s assuming that the people in charge of a particular area even want the vaccination program to go ahead. There have been entire sections of countries controlled by forces in opposition to it, such as Boko Haram in Nigeria and the Taliban in Afghanistan. They view it as undue Western influence on their territory, and rumors spread that the vaccines contain contraceptives to keep women from becoming pregnant, or that they will be damned by Allah because the vaccine contains products derived from pork. Things got even worse in 2011, when it came out that the CIA had used a fake Hepatitis B immunization effort in Pakistan to get DNA samples from the occupants of a compound in an attempt to verify the presence of Osama bin Laden there.

Still, eradication efforts proceeded as best they could, with more success. Polio was eradicated in India as of 2014, and after some false starts, all of Africa, including Nigeria, was declared polio free in 2020. Only Afghanistan and Pakistan still have wild poliovirus circulating, about 125 cases have been reported in the two countries so far this year. Much of the polio eradication resources have been redirected this year to combat the COVID-19 pandemic, and the WHO is concerned that a resurgence in polio cases is coming, but even so, health officials feel they are only a hair’s breadth away from finishing the poliovirus off forever.

Conclusion

The effects of polio on the Western World can still be seen today. Special wards in hospitals designed to treat polio patients developed into the Intensive Care Units that are a standard feature in hospitals today. Advancements in physical rehabilitation originally used on polio patients are used today for all manner of physical ailments. The concept of “crowd funding”, collecting small donations from many people as opposed to large donations from a few wealthy people, was first established as viable through the work of the March of Dimes. Today, crowd-funding is a cornerstone of all major nonprofit fundraising, and has expanded into the arenas of political campaigning and in private fundraising efforts, such as GoFundMe campaigns. Finally, the widespread implementation of the polio vaccine laid the groundwork for government regulation and control of the vaccine industry, and mandatory vaccinations for public school children persist to this day, leading to a direct reduction in communicable diseases worldwide.

As the world today is dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, we can look back hearteningly on the successful fight against diseases like polio, and realize that as long as we are willing to put forth the same effort, we can beat this disease as effectively as we did the poliovirus.

Additional Sources:

“The Polio Crusade” American Experience, PBS (Documentary)