The 5th century BC represented the pinnacle of cultural, political, and economical power for the city-state of Athens. It was a true golden age that would go on to have tremendous influence not only on the Greek world, but on all of Western civilization.

Socrates was laying down the foundations of Western philosophy, aided by students such as Plato, as well as other prominent thinkers of that time such as Anaxagoras, Empedocles, and Democritus.

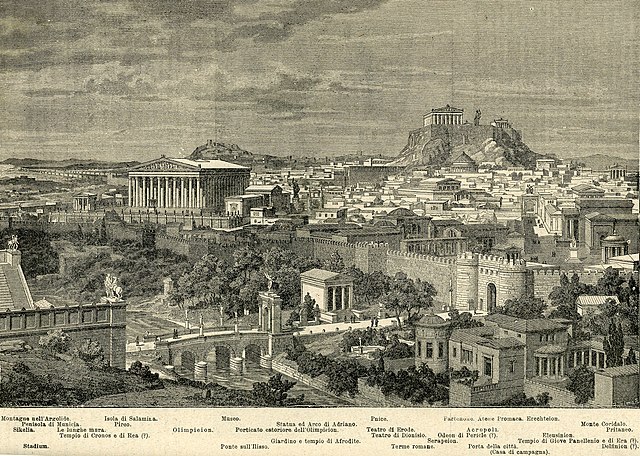

In the arts, Athenian theater was the envy of the Greek world thanks to talented playwrights such as Euripides, Sophocles, Aristophanes, and Aeschylus. A man named Phidias cemented his position as the best sculptor of his time when he made the Statue of Zeus at Olympia, ranked among the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Not to mention the fact that almost all the structures located on the Acropolis, most famously the Parthenon, were also built during this time.

Other Athenians thought that history was important enough to be recorded for future generations. Here we meet an old friend of Biographics, Herodotus, as well as Thucydides and Xenophon. The architect Hippodamus of Miletus was considered one of the founders of urban planning while Hippocrates pioneered western medicine and gave his name to the Hippocratic Oath. All of these great people lived and worked in one place, at one time.

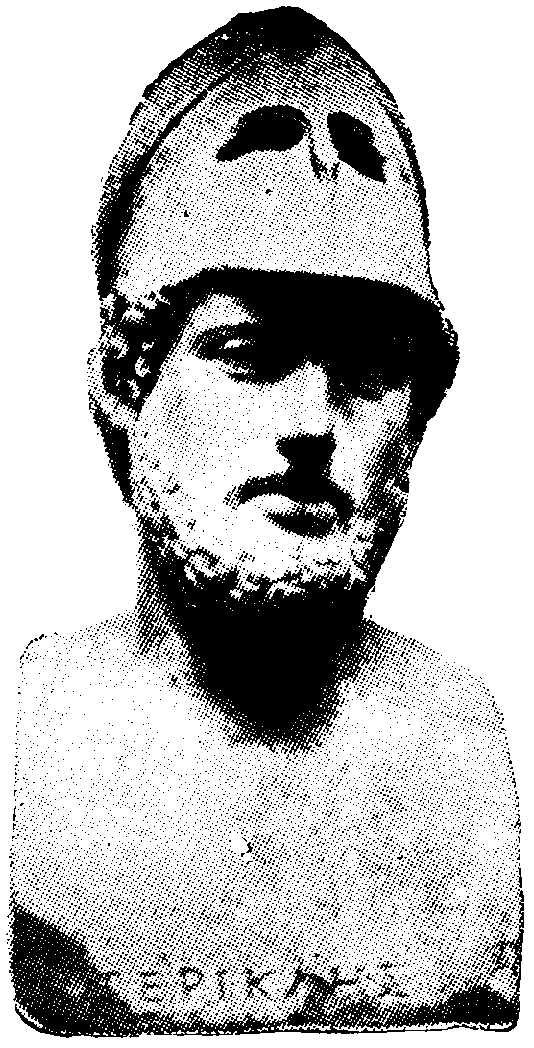

And then, of course, there was Pericles. Sometimes, this golden age of Athens is also called the “Age of Pericles” because he was there to support and oversee it all. He was the city’s leading statesman, a skilled general, a patron of the arts, and an orator without peers. Under his leadership, Athens flourished almost unlike any other city in history. It is no surprise, then, that Pericles became known as the “First Citizen of Athens.”

Early Years

Pericles was born circa 495 BC, in Athens, of course. His father was a wealthy politician named Xanthippus, while his mother was named Agariste and came from one of the oldest, most influential families in the city – the Alcmaeonidae. According to Plutarch, (who will serve as one of our primary ancient sources here) a few days before Pericles was born, his mother had a dream that she would give birth to a lion.

Afterwards, the historian goes on to specify that, even though Pericles’s personal appearance was “unimpeachable,” the Athenian apparently had quite a large and elongated head and, for this, he was often the butt of jokes of Greek poets. Plutarch says that Pericles’s head looked like a squill, also known as a sea onion, and that he was sometimes called “Schinocephalus” or squill-head.

Besides the unusual shape of his cranium, it was also said that Pericles greatly resembled in appearance a man named Peisistratus, a former tyrant of Athens who was not remembered fondly in his time. Therefore, as a youth, Pericles did not enjoy speaking in public and, instead, focused on his military career as he believed that that would be his biggest calling. It wasn’t until he got a bit older that he became more eager to enter the world of politics.

Given his family’s high status, it comes as no surprise that young Pericles benefited from a good education. Some of his known teachers included Pythocleides who taught him music, Zeno who educated him on the natural world, and, his most beloved tutor, Anaxagoras who told him about philosophy.

Despite his privileged childhood, Pericles saw firsthand how fleeting power can be. When he was around ten, his family’s status was almost wiped out when his father, Xanthippus, was ostracized. Back then, ostracism didn’t just mean that he got left out of Athenian politics, this was an official procedure that resulted in a 10-year exile from the city. However, in this case, it only lasted a few years, until the Persians invaded Greece again. As one of Athens’ most capable military leaders, Xanthippus was recalled in defense of the city. He acquitted himself very well when he led the Athenian navy in the Battle of Mycale in 479 BC. It was a decisive victory for the Greek cities and, together with another triumph at Plataea, marked the end of the second Persian invasion. Xanthippus only lived for a few more years after that, but he died a hero of Athens and ensured that his son would be welcomed into the city’s political world with open arms.

Athenian Politics

Before we get into the details of how Pericles rose to power, we should try to get some background on the ruling political classes of Athens. There are basically two groups that we need to discuss: the archons and the strategoi.

The archons were the chief magistrates of Athens and other Greek cities and they had been around for hundreds of years before the Age of Pericles. Basically, whenever Athens was not ruled by a king or a tyrant, it was ruled by these archons who usually came in three: the eponymous archon, the polemarch, and the archon basileus. The length of their office terms varied greatly depending on the exact time period we’re talking about. At first, they ruled for life, then they were limited to ten years and, finally, were restricted to a single year.

With the emergence of democracy, the power and influence of the archons diminished greatly. In fact, by the time of Pericles, the office of archon was mainly ceremonial, with just a few minor civic responsibilities. The authority was now in the hands of the strategoi. Generally speaking, a strategos simply meant a military leader; the ancient Greek version of a general. However, in 5th century Athens, there was a board always consisting of ten strategoi who were in charge of all the important duties of the city.

While other positions like that of archon were assigned by drawing lots, the strategoi were elected every year. All strategoi were technically of equal rank and made decisions through vote. However, as you might expect, some were considerably more influential than the rest and their opinion carried a lot more weight.

Rise to Power

Back to Pericles, he entered the political world of Athens when he was in his early 20s. The earliest recorded act of his is dated to 472 BC when he sponsored a play by Aeschylus called The Persians. In this case, Pericles was a choregos – a rich citizen of Athens who paid for the production of a play, whether he wanted to or not. These roles were usually assigned and, in fact, represented one of the few duties still performed by the archons but, in this case, it is believed Pericles wanted to sponsor this particular play to send a message.

Like we said, even though all strategoi were equal in rank, some were “more equal” than the others. At this time, the leadership of Athens was divided between two factions, one led by Themistocles, the other by Cimon. The play sponsored by Pericles evoked the Battle of Salamis where the Greeks led by Themistocles defeated the Persians. People regarded this as Pericles officially siding with him in his power struggle against Cimon.

Unfortunately for Pericles, he chose poorly. The list of enemies for Themistocles was growing larger and larger and it included all of Sparta who were friendly with Cimon. Eventually, after multiple accusations, Themistocles was ostracized and exiled. That wasn’t enough for Sparta, though, which accused the former war hero of aiding a Spartan conspiracy plot and wanted him tried by all the Greek cities, not just Athens. Since this likely meant a death sentence, Themistocles was forced to leave the whole of Greece and, of all places, he ended up in Persia which was now led by King Artaxerses I, the son of the man that Themistocles defeated in battle. Fortunately for him, the king was not interested in revenge. If anything, he was happy to have one of his father’s most capable foes in his service. The exiled Greek relocated to the prosperous city of Magnesia where he was named governor and spent the rest of his days.

Back in Athens, Pericles was steadily growing in power and winning over the people. However, he still had a major obstacle in the form of Cimon. Like Pericles, he was the son of a beloved war hero. In this case, Miltiades, the man who led Greece to victory at the Battle of Marathon. However, Cimon was also himself a distinguished military veteran, known for his triumph at the Battle of the Eurymedon. He was also richer than Pericles, and could afford to be more generous in his spending to win the affections of the public.

It seemed like Cimon had the clear advantage, but fortunes are often fleeting. All Pericles had to do was wait for the opportune moment to strike against his opponent and destroy his public standing. He first acted on some rumors that Cimon had taken bribes from Alexander I of Macedon. No, not the famous one. Who knows, Pericles may have even started the rumors himself. The important thing is that they allowed him to formally charge his rival with bribery and, even though Cimon was acquitted, it still attacked his credibility.

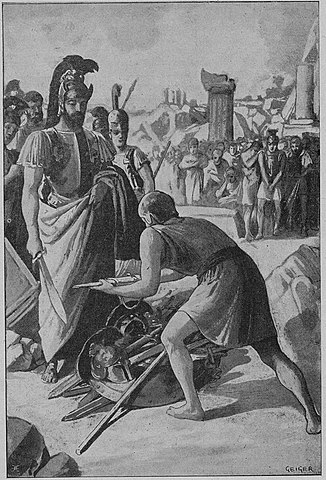

That being said, Cimon’s fall was ultimately of his own doing. As we said, he was close to Sparta. In fact, he acted as their proxenos – sort of an ambassador – and advocated for a close relationship between the two powerful Greek states. In 462 BC, Sparta experienced a helot rebellion, the helots being the lower class of Spartan society, similar to medieval serfs.

Cimon believed that sending soldiers to aid Sparta would help cement the bond between them. Other leaders were not as eager. With the Persians out of the picture, they saw Sparta for what it truly was – their main competitor and biggest threat. Even so, Cimon convinced everyone and personally led thousands of troops to Sparta. When he arrived, though, he received a very unpleasant surprise – the Spartans did not want them. In fact, the last thing they needed was for the helots to learn about that damn Athenian democracy. Cimon was turned back and had to return to Athens completely humiliated. Afterwards, Pericles had no difficulty in getting Cimon ostracized in 461 BC and exiled for ten years.

With the opposition gone, Pericles’s party was the most powerful political entity in Athens, but it was not led by Pericles. Not yet, anyway. It was led by its senior member and mentor of Pericles, a man named Ephialtes. He began enacting reforms to restrict the power of Athenian oligarchs and to expand the democratic privileges of the citizens, but he didn’t get to see his policies in action as he was assassinated that same year. Nobody knew who did the deed so, obviously, enemies of Pericles accused the Athenian of killing his mentor to take over his position. Such accusations were considered baseless. Plutarch, for example, said that they were “hurled, as if so much venom, against one…who had a noble disposition and an ambitious spirit, wherein no such savage and bestial feelings can have their abode.” He also mentions, quoting Aristotle as his source, that the killer of Ephialtes was a man named Aristodicus of Tanagra. Who he was, why he did it, and how Aristotle came to learn of him, we have no idea.

The point is that, with the leader of the opposition exiled and the leader of his own party dead, Pericles was now able to consolidate power and become the most powerful man in Athens, a position he would maintain until his death.

Athens VS Sparta

When Persia first began its invasion of the Greek cities at the start of the 5th century BC, Sparta was the unofficial, but uncontested leader of the Greek forces. After Sparta came its close allies who were all part of the Peloponnesian League, a group of city-states all located in or around the Peloponnese Peninsula. These included Corinth, Elis, Pylos, Kythira, and others. Finally, there were the rest of the Greek states that would probably not have been allies if they were not fighting a common foe, the Persians.

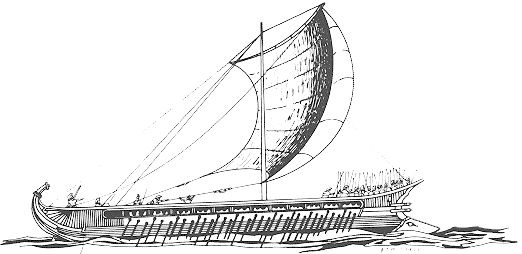

These last states came to resent Sparta, mainly due to two factors. For starters, naval warfare ended up becoming a very important factor in the wars. Sparta did not have a strong navy, not as powerful as Athens, for instance, or Argos, or Chalcis, or Chios. Therefore, these naval powers weren’t happy that their status in the alliance didn’t quite match up to the contribution they were bringing to the war.

Even more contentious, though, was the idea of a Greek counterattack. After the victories at Mycale and Plataea, the invasion of mainland Greece was over and, as far as Sparta was concerned, so was the war. The Greeks won, the Persians left, job done. But other city-states like Athens wanted to keep the pressure on and go into Asia Minor and liberate the Ionian Greek states which were still under Persian control and had been for almost a hundred years since they were conquered by Cyrus the Great.

At this point, Sparta and its close allies withdrew from the war and the leadership of the remaining Greek states was passed on to Athens. In 478 BC, they even formed their own association called the Delian League. The name came from the island of Delos which acted as a neutral meeting point for all the members, and also served as the league’s treasury.

Even in ancient times, historians such as Thucydides regarded the counterattack on the Persian Empire as just a pretext to form this league without opposition. The main goal was to protect its members from all future enemies and, although never stated, it was clearly intended to counteract Sparta’s Peloponnesian League.

From this point on, Athens’ power and influence in the Greek world steadily grew to the displeasure of Sparta. Over the following decades, the relationship between the two states became tense, even though it was still outwardly friendly. One important moment came when Athens rebuilt its walls in secret under the direction of Themistocles. Sparta insisted that no Greek cities should build walls, under the pretense that they would provide fortifications for a foreign invader if they took over the city. Of course, what others took this to mean was that Sparta preferred if the rest of the Greek states stayed reliant on them for protection. Well, Athens didn’t listen to Sparta, and not only did they build their walls, they also declared themselves free of Spartan hegemony, capable of defending themselves.

Over the years, the Delian League slowly, but surely turned into an unofficial Athenian Empire. Since its inception, each member was expected to provide an annual tribute in the form of either money or soldiers and weapons. With no immediate wars on the horizon, most members chose to pay, but Athens instead kept adding soldiers to the forces of the Delian League. After a couple of decades, the bulk of the league’s army consisted almost entirely of Athenian soldiers so, in reality, the other members were basically paying Athens to keep them safe.

This continued under Pericles who was eager to keep increasing the hegemony of Athens over the Delian League. At one point, he refused to accept any more soldiers or supplies as tribute, instead insisting that everyone pay money. The true turning point, however, occurred in 454 BC, when Pericles moved the treasury of the Delian League from the island of Delos to Athens. He did it under the pretense that the money was safer in Athens but, in reality, he used it to fund his own building projects. This was bad for them, but great for us, and great for history as a whole because Pericles’s most ambitious construction plan was to rebuild the Acropolis of Athens. Thanks to him, the city got marvelous structures such as the Propylaea, the Temple of Athena Nike, and, of course, the Parthenon.

His spending ways were not always well-received in Athens. In fact, they often represented the main criticism of Pericles by his political opponents. During the 440s, the other political party started gaining power again, led by a man named Thucydides, but not to be confused with the historian. The statesman wanted to have Pericles ostracized for playing fast and loose with public funds and, for a while, got the Athenian people on his side. However, in an example of supreme oratorical skill, Pericles managed to win back the public. He even said that he would pay for the construction from his own pocket, as long as the inscriptions were dedicated to him alone. The magnanimity of his offer was enough to sway the Athenians. Public spending continued as before, Thucydides was himself ostracized and exiled, and Pericles stayed in power.

The First Peloponnesian War

Ever since Athens started gaining power and influence in the Greek world, it was only a matter of time before it would collide with Sparta which did not want any other city-state to rival its strength. The year 460 BC saw the outbreak of the First Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta, as well as their allies. Just for added clarity, though, this is not the same as the more famous conflict known simply as the Peloponnesian War, which we will talk about in a bit. Technically, that should have been named the Second Peloponnesian War, but because it was much grander, lasted longer and had much more significant historical consequences, it became known just as the Peloponnesian War.

Ignoring the underlying tensions in the Greek world, this war ostensibly broke out due to a border dispute between Megara and Corinth. In 460 BC, Megara left the Peloponnesian League and requested to join the Delian League. This caused conflict between Athens and Corinth who were the initial belligerents of the First Peloponnesian War, with Sparta only intervening on occasion.

Pericles was reluctant to engage in an all-out battle with the Peloponnese forces because his army was spread far and wide, still aiding other nations in Asia Minor and Egypt who were rebelling against the Persians. He engaged the Corinthians several times and, eventually, managed to drive them out of Megara.

Meanwhile, Sparta spent the first few years of the war avoiding Athens. Instead, they battled Phocis, an Athenian ally, who themselves were in conflict with the neighboring state of Doris. Their goal appeared to be to conquer or submit all the city-states in the region of Boeotia and unify them all under one leadership.

It wasn’t until 457 BC that Sparta and Athens finally met in battle at Tanagra. According to Thucydides, the Spartans won, but “the slaughter was great on both sides” so they could not press on the attack and had to retreat. The Athenians, however, managed to regroup and, just a few months later, soundly defeated all the Spartan allies in the area at the Battle of Oenophyta, putting a stop to Sparta’s plan of consolidating power in Boeotia.

Pericles had the advantage, but it went away in 454 BC thanks to the Persians. Like we previously mentioned, a large part of the Athenian army was still assisting other nations trying to escape the subjugation of the Achaemenid Empire. The Delian League had sent 200 ships to Egypt to help a rebel leader called Inarus. The expedition ended in disaster for Athens following the Siege of Prosopis, as most of their fleet was destroyed, while Inarus was captured and crucified. This may have forced a peace treaty between Athens and Persia known as the Peace of Callias. More or less, it said that Persia would leave the Greek cities in Asia Minor alone, but Athens had to stay out of North Africa.

The disaster of the Egyptian campaign had serious repercussions for Athens as it lost its naval supremacy. Not only was it threatened by the Peloponnesian League, but also by Greek cities from the Delian League who wanted to rebel. This culminated in another defeat at the Battle of Coronea in 447 BC against all the Boeotian city-states that Athens had previously submitted.

From this point on, Pericles decided mostly to stay away from mainland Greece affairs and focus his efforts on the Aegean where Athens was most dominant. A surprise appearance here was made by Cimon, once the main political rival of Pericles. His exile was up so he returned to Athens in 451 BC. Still on good terms with Sparta, he first negotiated a temporary truce between the two powers which, eventually, culminated in the Thirty Years Peace of 446 BC, thus ending the First Peloponnesian War.

The Age of Pericles Ends

Don’t be fooled by the name of the Thirty Years’ Peace. It did not last three decades and nobody was expecting it to. Over the next 15 years, Athens and Sparta continued to act aggressively to one another, but they did it by proxy by finding cause to attack each other’s allies. The most notable example of this was the Samian War of 440 BC. Athens intervened in a conflict between Samos and Miletus. Even though Samos was a member of the Delian League, the city reportedly asked Sparta for help. The Spartans seriously considered going to war against Athens again, but backed out when Corinth would not join them since they needed the Corinthian fleet as the only naval power of the Peloponnesian League.

Strangely, the same cities that were involved in the outbreak of the First Peloponnesian War again played important roles. Megara, which was, once more, an ally of Sparta, had angered Athens by desecrating one of its holy sites. In reply, Pericles issued the Megarian Decree, banning Megarian ships and merchants from all markets and ports of the Delian League. It was the ancient Athenian version of a trade embargo.

Meanwhile, Athens also got involved in a dispute between Corinth and one of its colonies named Corcyra, today known as Corfu. Conversely, Corinth secretly aided a different colony named Potidaea with soldiers and weapons in a battle against Athens. These were all considered to go against the terms of the Thirty Years’ Peace and, in 431 BC, the Peloponnesian League led by Spartan King Archidamus II declared war on Athens once more.

Pericles’s strategy was to play to his strengths as much as possible. Athens dominated the waters, Sparta was unmatched on land. He knew that the enemy would come to ravage his territories, but decided to avoid an open battle. Instead, he relocated his people to the safety of Athens itself and, while the Spartan army was pillaging his farms, he took his navy and plundered the Peloponnesian coasts. Unfortunately, we cannot see the Peloponnesian War to its conclusion because, well, neither did Pericles. In 429 BC, just two years after the start of the war, the mighty statesman and half his family were killed by a plague that ravaged the city of Athens. The Peloponnesian War lasted for another 25 years and resulted in a definitive Spartan victory, thus bringing an end to the Golden Age of Athens, the Age of Pericles.