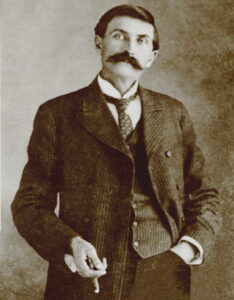

Pat Garrett once admitted that the thing he feared most was having his life defined by just one moment – the killing of William H. Bonney, better known as Billy the Kid. He said he dreaded meeting new people because they always said something along the lines of “Hey! You’re Pat Garrett, the guy who shot Billy the Kid!”

Unfortunately for the lawman, his worst fear came to pass. Not only in his lifetime, but also in modern times, his legacy is inexorably tied to the killing of Bonney, which I guess is just what happens when you gun down one of the biggest icons of the Wild West.

There was another problem. As the outlaw’s reputation grew and he was turned into a legend of the Old West, sympathy for him increased and Garrett, slowly but surely, was becoming the villain of this tale. Sure, Billy the Kid was a ruthless murderer who killed many men in cold blood, but people could not help but feel like Garrett acted somewhat cowardly by gunning him down in the dark. That was not how the heroes of the Wild West acted in their imaginations. If the two had met in a duel, then the story would probably have been remembered vastly different. Bonus “cool points” for Garrett if he would have said a snappy one-liner before shooting and lit a cigar afterwards.

As it stands, though, Pat Garrett sits in a grey area of western lore where some people admire him as a tough lawman in a lawless land and others brand him a coward. But, as we are about to see, his life continued with other thrills and adventures after the death of Bonney, culminating with Garrett’s own mysterious murder that still puzzles people to this day.

Early Years

He was born Patrick Floyd Jarvis Garrett on June 5, 1850, in Chambers County, Alabama, to John Lumpkin Garrett and Elizabeth Jarvis. At a young age, he relocated with his family to Louisiana after his father bought a cotton plantation in Claiborne Parish.

At first, things went pretty well for the Garrett family as the plantation flourished, but things took a drastic turn for the worse when the Civil War broke out. It completely ruined the family’s finances and then both parents died less than a year apart in 1867 and 1868, respectively, leaving behind a plantation full of debt. Pat’s younger siblings were taken in by various relatives. However, as Garrett turned 18 years old, he saw no reason to stick around anymore and, in 1869, rode alone into the sunset.

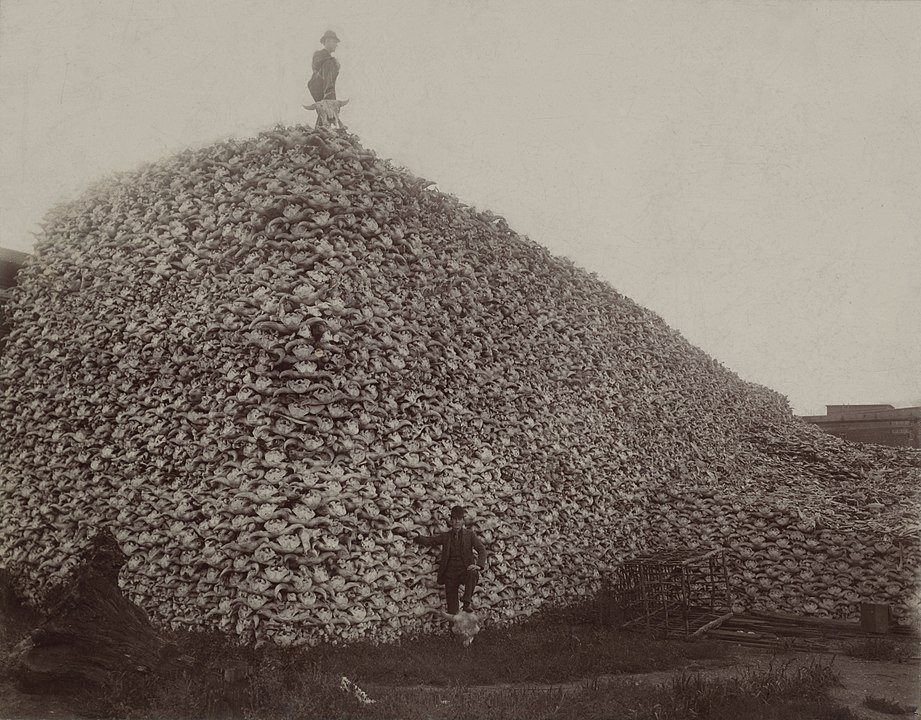

Very few details are known about the next years of Garrett’s life. He settled in Texas for a while, near the Dallas area, where he worked as a farmhand. A few years later, he became a buffalo hunter on the Staked Plains and started a business selling their hides. However, this was not a sustainable career. People like Garrett almost hunted the American buffalo (which is actually a bison if we are being technical) into extinction. Tens of millions of specimens were killed during the 19th century, at one point reducing their numbers to only a few hundred in the entire country. Once the supply started running out, Garrett left Texas and drifted towards Fort Sumner in New Mexico.

Before we get there, however, there is still another important event from Pat Garrett’s life to discuss – the first time he killed a man. It happened around 1876 and the victim was a friend of Garrett’s and fellow buffalo hunter named Joe Briscoe. The two of them got into an argument, who knows over what, and it escalated to the point of violence. An enraged Briscoe charged at Garrett with an axe, prompting the latter to grab a pistol and shoot his attacker at point-blank range. Allegedly, as he lay there dying, Briscoe was the one who asked forgiveness of his shooter, reducing Garrett to tears. Racked with guilt, the killer tried to turn himself in at Fort Griffin, but the authorities there had no interest in prosecuting him so Garrett just went on with his life.

When he arrived in New Mexico, Garrett found work as a cowboy again at Pedro “Pete” Maxwell’s ranch. This is the same house where he would kill Billy the Kid a few years later. During this time, he also married a woman named Juanita Gutierrez who would die less than a year into their marriage during childbirth. Garrett would not stay single for long, though, as in 1880 he remarried to Apolinaria Gutierrez, the 17-year-old younger sister of his first wife. They would go on to have eight children together.

The Lincoln County War

That same year, Garrett was elected sheriff of Lincoln County, New Mexico Territory, and immediately set his sights on Billy the Kid and the other gunslingers he rode with.

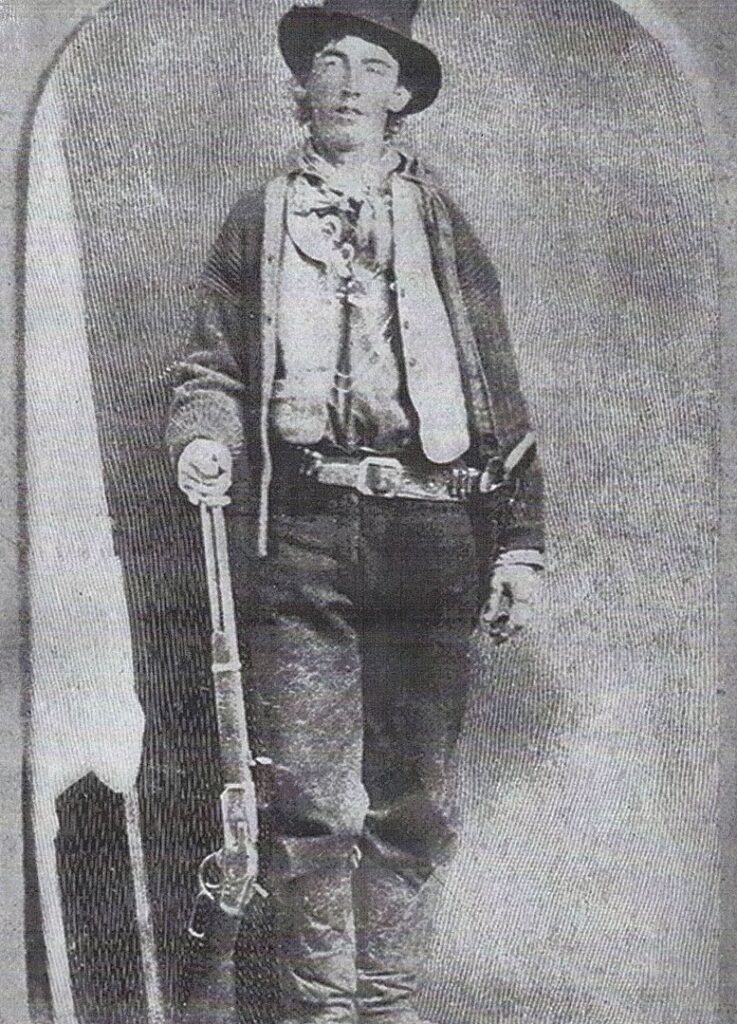

By this point, Billy the Kid had already earned his fame thanks to his involvement in the Lincoln County War which you can learn about in-depth in our Biographics video on “Billy the Kid”.

Basically, the Lincoln County War was a violent feud that started in 1878 between two factions that both wanted a monopoly over the dry goods business. On one side there was the older, established group led by James Dolan and Lawrence Murphy who already operated the largest general goods store in Lincoln County known simply as “The House”. On the other was the new partnership between businessmen John Tunstall and Alexander McSween who opened a rival store.

To add fuel to the fire, both groups also had some serious backup in the form of gangs willing to protect their side’s interests with violent diligence. Dolan’s faction had the Jesse Evans Gang, better known as the Boys, and also had the county sheriff William J. Brady in his pocket. The newcomers had the Regulators, a group of loosely-affiliated cowboys and ranch hands who had a history with one another. They included Billy the Kid and other desperados such as Dick Brewer, Doc Scurlock, the Coe cousins, Tom O’Folliard, and Charlie Bowdre.

The Lincoln County War kicked off properly on February 18, 1878, when the Boys killed John Tunstall. That’s when the Regulators formed into a more cohesive gang and, at the start at least, even had the law on their side as they received warrants from Justice of the Peace John Wilson to bring Tunstall’s killers to justice.

This feud was marked by multiple shootouts and revenge killings. Billy the Kid and a few other Regulators killed Sheriff Brady. Although dozens of other people died, this was the murder that would send Bonney on the run with Pat Garrett on his trail. The war culminated with a five-day shootout known as the Battle of Lincoln where Alexander McSween was also killed. With both businessmen dead, the Regulators had nobody to work for anymore so they scattered.

The First Pursuit

By the time Garrett started chasing Billy the Kid, the latter was already a notorious gunman known throughout the country. He and a few other Regulators like Bowdre and O’Folliard decided to stick together after the Lincoln County War and engage in additional acts of mayhem, violence, and murder. They also joined up with “Dirty” Dave Rudabaugh, another infamous outlaw of the Old West.

Billy the Kid’s gang first crossed guns with Garrett in late 1880. On December 19, the gang rode into Fort Sumner, New Mexico, where Garrett was already waiting for them, assisted by another lawman named Lon Chambers. He confronted Tom O’Folliard and another former Regulator named Tom Pickett. When O’Folliard went for his gun, Garrett shot him in the chest. He died less than an hour later, aged 22, but the other outlaws managed to make a run for it.

The lawman stayed in hot pursuit. Just a few days later, on December 23, he tracked the whole gang to an abandoned farmhouse near Stinking Springs, New Mexico, and, this time, he had a large posse with him. It seemed like Garrett had the situation completely in control, but the gang still preferred a shootout over surrender. Former Regulator Charlie Bowdre was killed during this encounter. The rest eventually came to their senses and gave up after a two-day siege.

The Kid Escapes and Second Pursuit

If this would have been the end of the road for Billy the Kid, Garrett might have been unanimously remembered as a hero. He was brave and diligent in his pursuit of the outlaws, only killed when absolutely necessary and managed to bring all the other criminals to justice. Unsurprisingly, Bonney was convicted for the murder of Sheriff Brady and sentenced to hang until he was “dead, dead, dead”, which is what the judge told him, according to legend.

However, on April 28, while awaiting execution, Bonney managed to outmaneuver his guards. When only one deputy named James Bell was watching him, he asked to be taken to the outhouse where he attacked his sentry. The Kid shot and killed Bell with his own gun. Afterwards, he armed himself with a shotgun, waited for Bob Ollinger, the other guard, to return and killed him, too. Bonney then jumped on a horse and rode out of town.

Garrett wasn’t in town when Billy the Kid escaped, but he soon returned and started chasing him again.

A few months later, the lawman heard that his fugitive had returned to Fort Sumner. He went to visit Pete Maxwell’s ranch because he suspected that Bonney might be hiding there. The exact sequence of events is up for some debate but, according to the most common version, on the night of July 14, Garrett was sitting in the dark in Maxwell’s bedroom. Bonney entered the room and asked who was there and, upon recognizing his voice, the sheriff shot him twice without saying anything. Billy the Kid was dead before he hit the ground.

Aftermath

Word of the outlaw’s demise traveled fast. As the story of Billy the Kid was plastered on every newspaper in the country, Bonney was slowly being turned into a folk hero rather than a lifelong criminal who was on the run after mercilessly killing two deputies. Moreover, Garrett was the one that the media chose to portray as the cold-blooded assassin.

He couldn’t stand this so, in 1882, he wrote his own account with the help of a ghostwriter to set the record straight. It was titled “The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid” and it became, for a while, the definitive version of the events that went down at Peter Maxwell’s ranch. However, it was later found to contain many inaccuracies and historians dismissed it as an embellished narrative with the occasional truth thrown in.

While the newspapers went way overboard with their sympathetic portrayal of Billy the Kid because it made a better story, Garrett’s account veered too much in the opposite direction as its main goal was to clear his own name rather than give a factual description of the events.

Most notably, Garrett’s version changes the part where he gunned down Bonney in the dark without giving him a chance to surrender. In a “Han shot first”-type scenario, the sheriff alleged that the Kid raised his cocked pistol a foot away from Garrett, thus leaving him with no choice but to pull the trigger.

Businessman Garrett

Garrett did not seek re-election as sheriff and, instead, had a brief stint with the Texas Rangers. After that was over, he left law enforcement for about a decade, time during which he tried to enter the irrigation industry.

Garrett lived on a large ranch near Roswell, New Mexico. He soon realized that in many arid, undeveloped regions of the Southwest, irrigation was a necessity for any kind of successful agriculture. In his area, that irrigation would have come courtesy of the Pecos River which Garrett thought could be dammed and used to construct a large-scale canal. One anecdote that definitely isn’t true even stated that he originally got the idea from Billy the Kid who told him that he could grow crops and make lots of money instead of chasing guys like him.

During the mid 1880s, Garrett met businessman Charles Eddy who was in the process of buying as much land as possible with his own plans to invest into an irrigation system. Eventually, the two decided to combine their ventures for one large reclamation project. They were also joined by a third entrepreneur called Charles Greene and, in 1888, the “Pecos Irrigation and Investment Company” was born.

As the company grew and more businessmen joined the project, Garrett was slowly relegated to an increasingly smaller role. Although this could have been done because others were simply more experienced than him, one Garrett biographer asserts that it was a deliberate effort to push him out of the company.

The lawman wasn’t quite ready to leave the business completely so, instead, he purchased one-third interest in the “Texas Irrigation Ditch Company” and formed another business called the “Holloman and Garrett Ditch Company” with entrepreneur William Holloman. Both companies failed and, eventually, Garrett abandoned this foray completely and relocated to Uvalde, Texas.

The Fountain Mystery

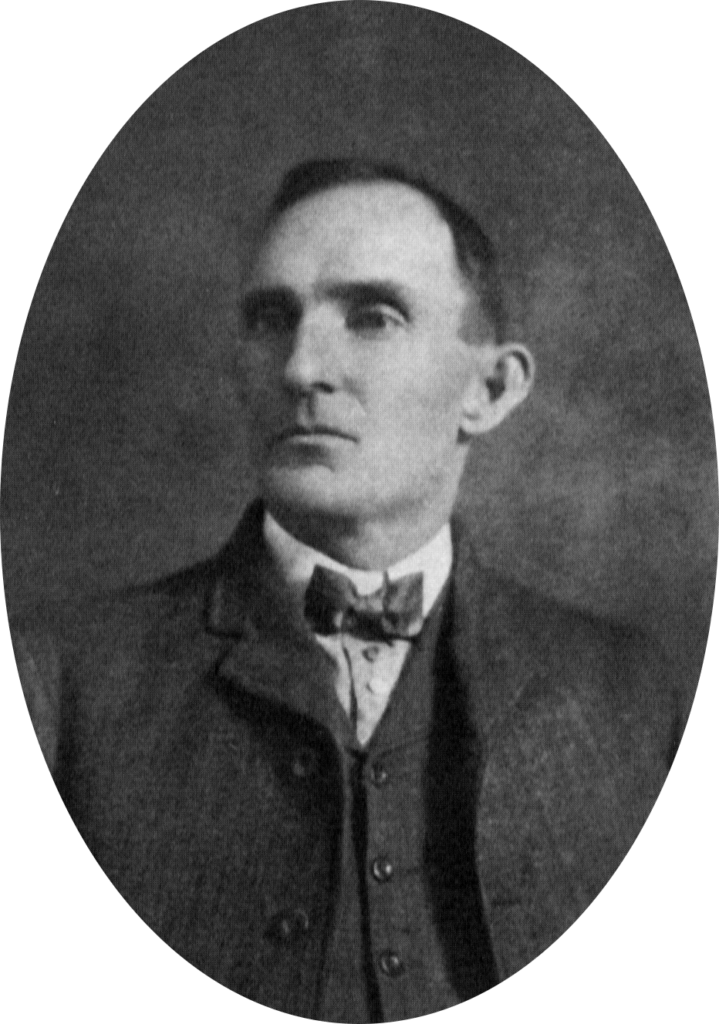

After almost a decade and a half of relative obscurity, Pat Garrett was, once again, in the headlines in 1896 due to his involvement in the disappearance case of Colonel Albert Jennings Fountain and his eight-year-old son, Henry.

Fountain was an attorney with the Texas Senate who made a lot of dangerous enemies when he went after powerful men involved in cattle rustling in the New Mexico territory. In late January, 1896, he and his son were traveling by wagon back home to Mesilla, New Mexico. They disappeared and were presumed murdered on February 1 near White Sands in Doña Ana County.

Suspicion fell on two wealthy ranchers and rivals of Fountain – Oliver Lee and Albert Fall. The scandal was front-page news across the country. Governor William Thornton wanted the matter resolved so he coaxed Pat Garrett out of retirement by making him the Sheriff of Doña Ana County.

Garrett located the spot where the presumed murders took place. The ground was soaked in blood and there was a smaller pool of blood a few feet away. Searching the area, the sheriff and his posse also found empty cartridge casings, Fountain’s tie, some of his papers, and his buckboard wagon stained with blood. It was pretty clear that something very violent took place there, but investigators were never able to find the bodies. To make matters more difficult, tracks that led away from the area had been “accidentally” erased by a passing herd of cattle which, by complete coincidence, belonged to Oliver Lee.

Garrett thought Lee was the culprit, alongside two of the rancher’s employees, Jim Gililland and William McNew. The sheriff obtained arrest warrants for all three. He placed McNew in custody, but the other two men made a run for it.

Garrett pursued the murder suspects and, on July 12, 1898, he caught up to them at the Wildy Well Ranch near the Jarilla Mountains. A shootout ensued, but it did not go in Garrett’s favor. One of his deputies, Kent Kearney, was hit twice. As his situation was deteriorating, the sheriff was forced to back down and call a truce so that he could get medical attention for his deputy. Kearney died on the way to Las Cruces.

The Trial

Lee and Gililland stayed on the run for another eight months before finally surrendering. At trial, they were represented by Albert Fall, the other landowner who hated Fountain and, according to some, might have even orchestrated the whole assassination plot. Now, Fall was not just a wealthy rancher. He was also a good lawyer and an influential politician. In fact, he would later serve as Secretary of the Interior under President Warren G. Harding. Thanks to his involvement in the Teapot Dome Scandal, Fall has the dubious distinction of being the first U.S. cabinet member in history to be convicted and serve prison time for a felony.

During the trial, Garrett’s reputation worked against him. Lee argued that the shootout at Wildy Well was in self-defense because Pat Garrett had no intention of taking him and Gililland alive. If they surrendered, the sheriff would have gunned them down in cold blood. This story alongside Fall’s adept defense and the lack of bodies ensured that the suspects walked away free, not even being charged in Deputy Kearney’s death. Not only that, but Oliver Lee went on to have a successful political career and today there is a state park named after him in Otero County.

Nobody else was ever charged in connection with the murders and the disappearance of Albert and Henry Fountain remains one of New Mexico’s biggest unsolved mysteries.

Presidential Appointee

The last highlight of Garrett’s law enforcement career happened in 1899 when he was pursuing a fugitive wanted for murder named Norman Newman. The chase ended in a gunfight where the sheriff shot the criminal and, thus, Norman Newman became, to our knowledge, the last man killed by Pat Garrett.

Garrett had a stroke of luck in 1901 when Teddy Roosevelt became President of the United States. Roosevelt had a deep fondness for famed frontier lawmen who he said “correspond to those Vikings, like Hastings and Rollo, who finally served the cause of civilization”. He gave jobs to several of them over the course of his two terms as president including Seth Bullock of Deadwood fame and Bat Masterson. Consequently, in 1901, Pat Garrett became collector of customs in El Paso.

Garrett’s appointment was not well-received. Despite numerous complaints, Roosevelt seemed determined to stick by his man. Allegedly, the last straw came when Garrett attended a presidential party and brought along a guest named Tom Powers. He introduced him to the president as a successful cattleman and the two took several photos together, only for Roosevelt to find out later that Powers was, actually, the owner of a notorious saloon in El Paso. After that, the president refused to renew Garrett’s appointment in 1905.

The Strange Demise of Pat Garrett

Most of the popular icons of the Wild West met violent ends and Pat Garrett was no exception. On February 29, 1908, he was shot on the way to Las Cruces, New Mexico, and died aged 57. Ostensibly, his killer was a man named Jesse Wayne Brazel who acted in self-defense. He turned himself in and confessed. At his trial, he was defended by none other than Albert Fall and he was acquitted. It would appear to be case closed, except that none of Garrett’s relatives and, indeed, most historians believe that Brazel was actually the one who pulled the trigger.

There are a lot of conspiracy theories floating around regarding Garrett’s murder. Here are the facts, as best we know them, and you can form your own opinion. Garrett was in a dispute with Brazel over some land that the former had leased to the latter for five years. Garrett wanted to break the lease when he discovered that Brazel was going to use his property for goat grazing. Also involved was a man named Print Rhode, a friend of Brazel’s and an enemy of Garrett who had run-ins with him while still a sheriff. We should also mention W. W. Cox, a wealthy rancher from the area who also hated Garrett and possibly wanted his land.

Eventually, the two sides reached an agreement where Brazel would terminate his lease if he had a buyer for his goatherd. That is where another man named Carl Adamson came in. The exact details of the agreement are a bit murky, but they are besides the point. What mattered was that on the morning of February 29, Pat Garrett, Adamson, and Brazel were traveling together to Las Cruces. That is when Brazel shot Garrett twice and then turned himself in to the Doña Ana County sheriff’s office, exclaiming “Lock me up! I’ve just killed Pat Garrett!”

Adamson acted as witness and corroborated Brazel’s story that an argument caused Garrett to reach for his shotgun but Brazel drew quicker. And, who knows, maybe this was, indeed, what happened.

There were a few things suspicious about Garrett’s death such as the fact that, allegedly, the former sheriff was shot in the back of the head and this was never brought up at trial. And speaking of the trial, how come, of all people, Albert Fall was the one who defended Brazel? He had close ties to the judge and the prosecutor in the case and also rancher W. W. Cox who some see as the mastermind of this whole plot.

Garrett’s son believed Adamson was the killer and some agree. Others think it was Print Rhode who caught up to the trio and took his revenge. And there’s another major suspect we haven’t even mentioned yet – an outlaw named Jim Miller, better known as “Killin’ Jim” or “Killer Miller” who sometimes acted as gun-for-hire and just happened to be in the area. One popular theory says that Miller was paid by Cox to do the deed.

We probably won’t agree on what happened since none of us can know for certain. What we can agree on is that getting shot in the back of the head and being dumped on the side of the road was a disgraceful, undeserving end for a man once called by “Billy the Kid” historian Walter Noble Burns as the “last great sheriff of the old frontier”.