In 1976, a new American made-for-television film aired for the first time, introducing a World War II based series titled Baa Baa Black Sheep. It purported to tell the story of a US Marine fighter squadron that served in the Solomon Islands Campaign in the Pacific Theater and was based on the autobiographical book of the same title, written by the squadron’s former commander, US Marine Major Greg “Pappy” Boyington. The series featured Robert Conrad, whose most famous role up to that time had been of James West in the series The Wild Wild West. The real Boyington, then still alive, served as a technical consultant, and later appeared in cameo roles in three episodes of the program, which eventually was retitled Black Sheep Squadron and ran for a total of 36 episodes.

Critics viewed the program with disdain. The Washington Post called it “war is swell”. The program relied on long-established Hollywood cliches. The premise was that of a group of misfits, contemptuous of military regulations and discipline, escaping the wrath of their superiors due to their heroic performance against the enemy in combat. The pilots of the Black Sheep Squadron were hard drinking, two-fisted, all-American boys, constantly at odds against the hide-bound military establishment as they battled bad weather and chronic shortages of parts for their airplanes, food, and female companionship. The only thing they had in plenty was Japanese pilots trying to kill them. Against these they invariably prevailed, thus escaping disciplinary action for their indiscretions and gaining the adulation of the press and public.

Even Boyington referred to the series as “…Hollywood hokum”. The true story of Boyington and his World War II exploits was obscured by Conrad’s version, which was and remains a travesty. The real Boyington, whose career was remarkable, served in the US Army before World War II, resigned his commission to join the Flying Tigers fighting the Japanese in China, changed his legal identity to enlist in the Marine Corps in 1942, and was eventually shot down by the Japanese, captured, and spent more than a year in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps. He was one of the first American flying aces of the war, eventually shot down more than two dozen enemy airplanes, and was awarded the Medal of Honor for his performance. After the war, he could barely hold down a job.

This is the true story of Gregory Boyington, nicknamed Pappy by the much younger pilots who served under him. It first appeared in his autobiographical memoir, was greatly fictionalized by television, and has only recently been more accurately documented by historians and aviation buffs. As is so often the case, the truth is greater than fiction. As Life Magazine wrote in 1945, following his repatriation as a former PoW, “Boyington was born to be a swashbuckler.”

An Abusive Childhood

Greg Boyington grew up under another name. His biological father was a dentist named Charles Boyington, who married Grace Gregory in January, 1912. Their son, Greg, was born in December of that year. By then the marriage was already in trouble, the couple dysfunctional, with alcohol and infidelity on the part of both parents present. Shortly after Greg’s birth, a fire destroyed the hospital where he had entered the world, also destroying his birth certificate. Charles abandoned the family when Greg was just three months old, and a year later, his mother obtained a divorce. In the spring of 1915, Grace began residing with Ellsworth Hallenbeck, though whether it was through a legal marriage remains a subject of debate. They settled in a small lumber community near Coeur d’Alene in Idaho, where Ellsworth worked as a bookkeeper. Young Greg grew up believing his last name to be Hallenbeck.

Ellsworth proved to be as heavy a drinker as had Charles before him, prone to domestic violence and emotional abuse, and dismissive of his role as a stepfather. The family moved frequently, often because rent money had vanished into barroom tills or liquor stores.

Later in life, Boyington found had few fond memories of his childhood, at least as far as his domestic life was concerned. He did reminisce with some happiness over his Idaho boyhood away from the home, where he enjoyed the outdoors, particularly climbing the steep wooded hills. He was an average student in school, and an avid consumer of news, particularly war news as Europe convulsed itself in what was then called the Great War, later known as World War One. He was particularly enamored with the tales of a new type of warrior, the fighter pilot. He listened to the exploits of the heroes of the sky, the Red Baron, the Allied ace Raoul Lufbery, the tales of the American Lafayette Escadrille, and later those of American heroes such as Eddie Rickenbacker.

Following the war barnstorming pilots toured the United States, giving demonstrations, presenting air shows, and offering rides to those interested. In September, 1919 one such aviation daredevil, Clyde Pangborn, provided the young Greg Hallenbeck his first ride in an airplane, in return for five dollars. Where Greg got the money remains unknown; he later told different stories of how he obtained it. He had by then already decided upon a career in the military. From then on, he dreamed of becoming a military flyer.

In high school, Greg came into his own both academically and athletically. He maintained above average grades in his studies, lettered in wrestling, excelled in swimming, and proved popular with fellow students, an achievement which had up to then eluded him. Following high school, he entered the University of Washington in Seattle. Then, outside the dysfunctional home, he continued to do well, joining the Army Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) and concentrating his studies on architecture. Though he lacked a scholarship, he was invited to join the wrestling team at his coach’s request. He also visited the nearby Boeing Aircraft Company’s factory, where he admired the new designs of airplanes being produced.

The visit inspired him to change his major from architecture to aeronautical engineering. In 1933, he attended an ROTC dance, where he met a young woman named Helene Clark. They were married in July 1934. The following May, Helene gave birth to their first son, Gregory Hallenbeck Jr. Greg Sr had graduated the preceding January, and with a family to support, he went to work at Boeing as a draftsman, reviewing airplane drawings and dreaming of flying. He could not afford an airplane, nor even regular access to one, but he could at least work near them.

Early Military Life

Greg’s ROTC membership obligated him to a period of active duty upon graduation with the United States Army reserve. He fulfilled that obligation by serving in the artillery at coastal fortifications around the Puget Sound. The artillery was not to his taste, and upon completion of his mandatory service, he entered the inactive reserves. In April, 1935 he learned of the recent passage of the Aviation Cadet Act by Congress, which offered qualified candidates a year of flight training for service in the United States Navy or Marine Corps. There was a problem though. The Navy would not accept married men as candidates, and since the Marine Corps was under the jurisdiction of the Secretary of the Navy, neither would they.

It was around this time that Greg learned, possibly through his mother, that his real name was Gregory Boyington, not Gregory Hallenbeck. In an early example of his tendency to exploit legal loopholes to advance his own interests he realized that, according to existing documentation Gregory Hallenbeck was married, but Gregory Boyington was not. Nor was there any legal paper establishing Gregory Boyington as a father. Accordingly, it was Gregory Boyington who applied for entrance into the Marine Corps as part of the aviation training program. He was accepted and embarked upon a period of deception, keeping his wife and family a secret from the Marine Corps.

The deception caused financial hardship for Boyington. He was forced to house his family at his own expense off base, while at the same time keeping up appearances as a young, single, pilot trainee while living on base. Officers at the time paid for their meals, including while aboard ship, and also paid for the upkeep and maintenance of their extensive uniforms. He proved eager to display the behavior of a young, single, pilot cadet, both in his early training in Washington and later during advanced training in Florida. In essence living a double life, Boyington rapidly ran up significant debts.

Boyington struggled with ground school and theoretical training, though he excelled in flight. In 1937, he was awarded his wings as an aviator. He had by then developed the reputation of being an excellent and skilled pilot. He was also considered to be somewhat of a slouch at paperwork, contemptuous of the spit and polish tradition of the Marine Corps, and an enthusiastic consumer of whiskey both in on base clubs and off base watering holes.

His next assignment was in Quantico, Virginia, and he moved Helene and his son, soon to be joined by a daughter, to Virginia, again at his own expense. The double life continued to generate financial difficulties, and his frequent absences put additional strain on the marriage. Soon Helene was drinking excessively as well. In 1940, another daughter was added to the clan. Debts continued to mount. Meanwhile, the rest of the world went to war, due to German aggression in Europe and Japanese aggression in China. That same year, the United States was officially neutral even as the US government adopted ever more open policies supporting the Allies in Europe, and aimed at controlling Japanese expansion in the Pacific.

The Flying Tigers

By 1941, Boyington’s marital status was known to his superiors in the Marine Corps, though officially the circumstances of his deception were ignored. Also known to the Corps was his indebtedness. When creditors contacted the Marines demanding action, his pay was taken over by the Corps, which allotted most of his salary toward reducing his debt, leaving little to support his family. Then a new program emerged which offered the potential for some relief. It was in the form of yet another idea from the mind of Franklin Roosevelt which afforded the United States an opportunity to improve its military readiness, offer aid to allies, and still present an appearance of complete neutrality. It was called the American Volunteer Group or AVG.

Boyington had returned to Pensacola as a flight instructor when that facility was visited by representatives of the AVG in 1941. At the time, he was under the threat of a court martial for having been involved in a fistfight. That charge, as well as his history of indebtedness, threatened his career with a dishonorable end.

The AVG offered a solution to all of his pressing difficulties. AVG pilots would be recruited to serve as paid civilian volunteers fighting the Japanese in China. They would receive the princely sum of $500 per month, more than double what was Boyington’s pay as a Marine. In addition, another $500 would be paid for each Japanese aircraft destroyed by a pilot. The pilots would be civilian contractors, outside the jurisdiction of the American military and not subject to its regulations. In order to meet that requirement, military aviators were required to resign their commissions, though it was with the understanding that they would be reinstated without penalty at a later date, upon their request.

In reality, the AVG was a quasi-military organization funded by the US government, operated by former senior military officers, and intended to both support the Chinese fighting Japan and acquire valuable combat experience for American pilots. They were provided with one of the newest and most capable combat aircraft available in the American inventory, the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk. They were to be commanded by Claire Chennault, already a legend in American military aviation.

Boyington jumped at what must have been seen by him as nearly divine intervention. In 1941, he resigned from the Marine Corps, joined the AVG, and made the journey to China via ship across the vast Pacific. In theater, he quickly developed a reputation of being a drunk with an exaggerated opinion of his own abilities as a leader and as a pilot. Chennault supported that assessment, though Boyington’s flying abilities were unquestioned.

The men painted shark’s teeth on the noses of their P-40s, an image which originated with British pilots operating the airplane in North Africa. When members of the press saw the airplanes, they dubbed them the Flying Tigers. Contrary to popular belief, the Flying Tigers did not begin operations against the Japanese prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor in December, 1941. Boyington and his new colleagues did not fight the Japanese until early 1942, attempting to stem the enemy’s invasion of Southeast Asia and Burma. During his brief tenure with the unit, Boyington claimed to have destroyed six Japanese aircraft, a figure which was later accepted by the Marine Corps. AVG records credited him with two, and possibly another two destroyed on the ground.

The entry of the United States into the war caused Boyington to reconsider his status. In April, 1942, he abandoned his contract with the AVG and returned to the United States, paying for the then perilous journey with his own funds. Upon arrival, he presented himself to the Marine Corps with a request for a return to service. His troubled marriage ended in divorce as he prepared to return to active duty, with Boyington charging the mother of his children with neglect. His three children were sent to live with their grandmother while extended duty overseas beckoned for their father.

Despite his checkered past, the Marines needed aviators, particularly those with combat experience against the Japanese. On September 29, 1942 Boyington was commissioned and assigned to serve as the executive officer, or second in command, of a fighter group then serving on the embattled island of Guadalcanal.

Baa Baa Black Sheep

Boyington returned to combat operations on Guadalcanal in early 1943. Marine fighter aircraft operations at the time were primarily focused on providing close air support to ground troops and attacking Japanese shipping in and around the islands. By August, 1943 he was in command of another Marine fighter squadron at Henderson Field on Guadalcanal, though through that period he was not credited with destroying any Japanese aircraft.

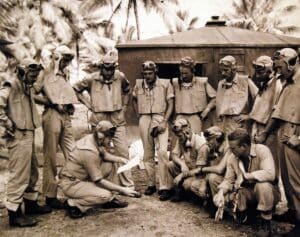

In September, Boyington was ordered to report to the island of Espiritu Santo, in the New Hebrides Island group, to assume command of 27 pilots in the then untested combat squadron designated VMF-214, VMF being the designation for Marine Fighter Squadron. The group had recently been formed in Hawaii, and were known by the nickname “Swashbucklers”. Under Boyington, the squadron adopted the nickname of Black Sheep. Unlike the legend which arose surrounding them, they were not a conglomeration of misfits and trouble causers. Instead, they included both veterans of combat in the Solomons and new replacements from Hawaii. In fact, the only pilot in the squadron with a reputation of being somewhat of a problem child was Boyington himself.

The aircraft they were assigned were older, many of them in relatively poor condition due to the number of hours they had been in the air. Spare parts were scarce, as was ammunition. Though the pilots themselves were not initially the scofflaws depicted in legend, they quickly adopted the long-established military tradition of circumventing channels and resorting to barter or outright theft to meet their needs. Boyington fully approved of such methods, though his military superiors did not.

The squadron was equipped with the Vought Corsair, a well-armed, gull-wing equipped fighter, which proved to be a match for the Japanese Zero fighters as well as a capable ground support and bomber aircraft. Learning to fly the Corsair proved tricky, as the pilot’s seat was situated well behind the nose, causing visibility problems when landing. The Navy decided the Grumman Wildcat, and later the Hellcat, was a better choice for aircraft carrier operations due to the difficulties encountered when landing. Navy inventories of Corsairs were assigned to the Marines, most of which operated from shore bases.

After just a month of preparation, the Black Sheep were ordered to Guadalcanal, and then to the Russell Islands, where they operated from airfields on Munda and Vella LaVella. Their primary mission was to provide aerial cover for Marine and Navy operations, and fighter escort for bombing missions against the Japanese strongholds at Rabaul and Truk.

They were forced to cannibalize damaged aircraft for parts in order to keep some of the squadron flying, and were not averse to rerouting spare parts originally intended for other groups. Ammunition, fuel, tires, radios, spare parts, and nearly all items necessary to keep a squadron flying were all in short supply during the summer and fall of 1943. Pilots frequently were forced to abandon missions and return to base due to mechanical failures. Yet they persevered, often flying aircraft which were, at least according to standard operating procedures, not airworthy. Pappy never turned back, often flew the least reliable airplane, and inspired his pilots to emulate him.

During that time, the Black Sheep were credited with destroying 203 Japanese aircraft in the air or on the ground. Nine of its pilots became aces, meaning they had five or more confirmed air-to-air victories. Boyington led the way, reaching a total of 26, surpassing Eddie Rickenbacker as America’s all time leading ace pilot at that time. He became a national hero, a media darling, and the hard-fisted, hard-drinking, hard-charging American of myth, barely patient with authority, fearless of the enemy, admired, even idolized, by his men. The Black Sheep were lionized in newspapers, newsreels, and magazines. Pappy, so-called because he was more than 10 years older than most of his young pilots, was their undisputed leader.

In one mission Boyington led, reported at the time and later embellished by subsequent reports the squadron, he orbited above a large Japanese airbase at Bougainville, daring the Japanese pilots to rise to intercept their Corsairs. More than 60 Japanese fighters were lured into combat, with 20 of them shot down by the two dozen Black Sheep. None of the Marines were lost, though several aircraft suffered combat damage.

On January 3, 1944, Boyington led the Black Sheep and elements from other Marine squadrons in an action near Rabaul, a Japanese military stronghold on New Guinea. Pappy did not return from the mission. His wingman was shot down and killed, and none of the other pilots involved could report with accuracy what had happened to their leader. An extensive search of the area by air and sea did not reveal any trace of Boyington, nor his airplane.

The Happy Return

During the Second World War it was customary for the warring nations to inform their enemies of the status of prisoners of war via the Red Cross. The Japanese did not always follow such courtesies. With no information from any source, the Navy Department listed Boyington as Missing in Action or MIA. Such was Boyington’s status when he was awarded the Medal of Honor in March, 1944. The medal, awarded by President Roosevelt, cited the period of September 12, 1943 to January 3, 1944 and noted his “…daring and courageous persistence”, as well as his personal total of 26 enemy aircraft destroyed. The medal was held in the Navy Department against final knowledge of Boyington’s fate.

In fact, Boyington was a prisoner of the Japanese. After he was shot down, he was picked up from the sea by a Japanese submarine, transported to Rabaul, and later transferred to Truk, finally being shipped from that base to a prison camp at Omori, Japan. He spent a total of 20 months in captivity, with the Japanese never according him prisoner of war status. Among the prisoners with whom he was detained were Louis Zamperini, later the subject of the film Unbroken, and Richard O’Kane, former commander of the submarine USS Tang, the most successful American submarine of the war.

There were rumors of Boyington being alive during his period of captivity, many reported in newspapers in the United States. He was afforded no mail privileges. Not until August, 1945, following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, did the Japanese acknowledge they held the Marine pilot as a prisoner. Like most prisoners who survived Japanese captivity, Boyington was nearly emaciated when released. Ironically, later in life he claimed that his health improved in captivity, as it was the longest period of sobriety in his adult life he had ever experienced.

Released from captivity he experienced a burst of fame, enjoying his status as the returning conquering hero. He retrieved his Medal of Honor, and was awarded the Navy Cross, the second-highest award for valor given by the Navy. President Harry Truman bestowed the Navy Cross, in which Boyington was cited for “…extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession…”

He represented the US Marine Corps in a Victory Bond Tour before retiring in 1947 as a full Colonel. He found it difficult to hold a job, resuming his heavy drinking. He married for a second time, a marriage which also ended in divorce. A third marriage, and later a fourth, suffered similar fates.

He bounced from job to job, including stints as a brewery manager, a stock broker, sales jobs for multiple products, and even as a referee for professional wrestling. At times he even wrestled. None of his jobs lasted long, as heavy drinking and late hours made him unreliable.

In 1958, he published his autobiography, which focused on his World War II years, under the title Baa Baa Black Sheep. It was moderately successful. He later wrote a novel, Tonya, which featured espionage affecting the AVG, based on his personal experiences, and characters, from his time with the Flying Tigers. Gradually, he faded into obscurity, known only to World War II buffs and Marine aviators.

Legacy

Pappy Boyington received another burst of fame when the television series Baa Baa Black Sheep appeared in the 1970s. The program did not last two full seasons, and despite Boyington being credited as a technical advisor it was panned by critics and by surviving members of the Black Sheep Squadron. Boyington received some money from the program, and survived largely through paid personal appearances and speaking engagements at air shows and conventions.

Boyington died from complications from lung cancer in Fresno, California in January, 1988. He was buried, with full military honors, at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. In a ceremony conducted in Fresno before his body was flown east, a formation of US Marine fighters from VMA-214, then known as the Black Sheep Squadron, flew by in a salute. Their formation was one aircraft short, with one having aborted the mission due to mechanical issues with the airplane. It was perhaps the most fitting tribute of all.