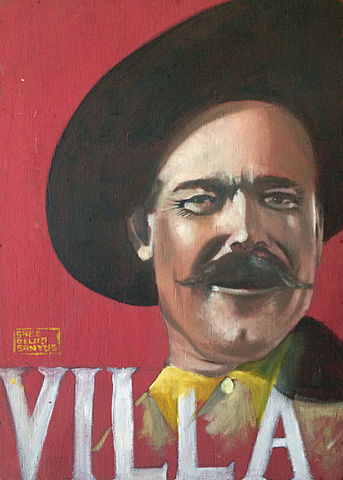

Pancho Villa was one of the most divisive figures in history. To millions he was the Mexican Robin Hood, to others a ruthless terrorist who killed without conscience. What is without doubt is that he rose from humble beginnings to become one of the most famous Mexicans in history, playing a vital role in the decade that shaped modern Mexico. In this week’s Biographics, we discover the real story of Pancho Villa.

Beginnings

There is a lot of mystery surrounding the early life of the man who became Pancho Villa. Most historians believe that he was born on June 5th 1878 in the tiny village of Rancho de la Coyotada in the state of Durango, Mexico. His birth name was Jose Doroteo Arango Arambula. When he was a few years old, his father, Agustin Arango, died. This meant that Doroteo, the oldest of five children, had to start working on the hacienda. Getting up at three o’clock in the morning, he had to walk for ten miles to start work at five. The work consisted of planting corn and running errands.

Villa later claimed that he never attended a day of school in his life. When not working, he liked to play cards and was often getting into fights with his peers. During his teens he held a number of jobs including muleskinner, bricklayer and butcher. Then, at the age of 16, he moved to Chihuahua for work. The story goes that two years later he returned to his home town in order to hunt down a man named Agustin Lopez Negrete, who had raped his sister. He apparently found the rapist and killed him. This episode is said to have set him on his life of crime. He fled to the Sierra Madre mountains and joined a group of bandits, changing his name to Pancho Villa.

The bandits, who numbered between 40 and 50 men, raided the ranches of the wealthy to steal cattle and horses. They lived in the mountains and trained as guerrilla fighters. Their reputation as fighters against the system established them as freedom fighters in the minds of the poor, who gave them shelter and warned them when the rurales, or rural police force, were closing in.

In 1902, Villa was captured by the rurales. According to the practice of the times, he was inducted into the Federal Army. He spent several months in the army and then deserted, heading back into the hills to rejoin his gang. Around this time, he killed an army officer, which made him one of the most wanted men in northern Mexico. A reward of ten thousand pesos was placed on his head.

Pancho became the leader of his bandit group and continued to lead increasingly violent raids upon the wealthy. The legend says that he would sometimes risk capture by walking openly through the streets of Chihuahua to distribute money to the poor. In so doing, he won the loyalty of the people, who helped to protect him from the authorities.

Revolution

In 1910, Mexico seemed to be a model of democratic stability. Porfiro Diaz had been president for 30 years and the country was celebrating 100 years of independence. But Diaz ruled with an iron fist and the elections that were held every four years were merely a façade to appease foreign governments. Ninety percent of the country lived in poverty.

Since 1906, there had been a number of worker rebellions against the conditions they were forced to exist under. Each one had been forcibly put down by the Diaz regime. A number of intellectuals began writing against the regime, including a man named Francisco Madero, who decided to run for President in 1910. When his campaign began to gather momentum, however, President Diaz had Madero arrested and thrown in prison. The mock election went ahead and Diaz was re-elected for the seventh time.

Madero managed to escape from prison and fled to the United States. From there he began planning for revolution. Meanwhile, down in Chihuahua, Pancho Villa had established a reputation as a kind of Mexican Robin Hood, a champion of the underprivileged. But he was also known as a wild man, a ruthless killer who would shed blood with impunity. Seeking respectability, he met with a supporter of Francisco Madero by the name of Abraham Gonzalez. By aligning himself with Madero, Gonzalez told Pancho, he would be able to re-invent himself as a legitimate man of the people. Villa agreed and he threw the support of his bandit group behind the revolutionary cause.

By now Pancho had developed a strong hatred for the regime of Porfiro Diaz, along with the exploitary landowners and the rurales who had been hunting him for more than a decade. He and his men brought skills to the revolutionary cause that had been honed over years of raiding, fighting and evading the authorities. In battle, Pancho fought like a man possessed and now that he had an established cause, he was even more ferocious. He also proved himself as a master of military tactics, brilliantly marshaling his small band against much larger government forces.

On one occasion, at the battle of Escobas, Pancho put hats upon planted sticks in order to fool the rurales into thinking that he had a much larger army than he actually did. By the beginning of 1911, that army had grown to more than 400 people and was racking up decisive victories over the Federal Army at such places as Naica, Camargo, and Pilar de Conchos.

In early 1911, there was a challenge to the revolutionary leadership of Madero from the ultra-radical Mexican Liberal Party. To put down the challenge, Madero turned to Pancho, who moved in and arrested the leaders of the party. A grateful Madero rewarded Villa by making him a colonel of his revolutionary army.

In May, 1911, Madero’s 3000 strong force, with Villa at the forefront, laid siege to the key border city of Ciudad Juarez. The town was guarded by 500 Federal troops, along with 300 civilian auxiliaries and local police. The fighting went on for two days at the end of which the Federals surrendered.

On May 25th, with his armies being defeated and public opinion unanimously against him, President Diaz resigned and fled into exile. A free and fair election was held in which Francisco Madero was elected President.

Madero signed the Treaty of Ciudad Juarez by which the Federal Army would remain in place. He, therefore, ordered the disbanding of his rebel army to return to their pre-war lives. Madero allowed the structure of the Diaz government to remain. To Pancho Villa this was a fatal error, and he let his feelings be known, telling Madero . . .

You sir, have destroyed the revolution. It’s simple; this bunch of dandies have made a fool of you, and this will eventually cost us our necks, yours included.

Division

Villa and his fellow revolutionaries were also incensed that Madero refused to distribute seized hacienda land to veterans of the struggle as payment for services rendered. Villa became increasingly critical of Madero’s actions, especially his putting a former supporter of deposed President Diaz as Minister of War. Even more outspoken, was a fellow revolutionary leader by the name of Pascual Orozco.

In March, 1912, Orozco led a rebellion against the new regime. Madero called on Villa to put it down. Despite being urged by Orozco to join the revolt, Pancho led his army of 400 in conjunction with Federal forces in a series of decisive victories that quashed the rebellion.

Following the victory against Orozco, Villa’s band joined up with Federal militia in the city of Torreon in the state of Coahuila. The Federal commander, General Victoriano Huerta, detested Villa. He was initially welcoming, showering him with praise and awarding him an honorary generalship. But the pleasantries didn’t last long, with Huerta accusing Pancho of stealing a horse. With his honor publicly impugned, Villa responded by slapping the general. This was the pretext that Huerta was after and he promptly had Villa arrested and charged with insubordination. An execution by firing squad was ordered. Word of the affair reached President Madero who telegraphed Huerta and ordered him not to execute Villa but to keep him as a prisoner.

Villa was sent to the Belem Prison in Mexico City. While incarcerated there he learned to read and write under the guidance of a fellow prisoner. In June, he was transferred to a prison in Santiago. Six months later he escaped, jumping onboard a train bound for the United States. On January 2nd, 1913 he arrived in El Paso, Texas.

While in prison, Pancho had learned of a planned coup against Madero. He attempted to get a warning message through to the president, but it never arrived in time. On February 22nd, 1913, Madero was gunned down on the orders of General Huerta, the man who had come so close to executing Villa a year earlier.

Huerta now installed himself as the President of Mexico. Villa was incensed at this series of events. Even though he had become disillusioned with his actions upon gaining power, he still viewed Francisco Madero as the apostle of democracy and his personal role model. Now that Huerta, his personal enemy, was in power he knew that he had to return to Mexico. He felt the mantle of completing the dream of democracy that Madero had instilled in him was upon his shoulders.

Deposing Presidents

The Mexican people were just as upset as Villa at the turn of events. Except for the wealthy businessmen who were relieved by this ‘return to order’, the vast majority viewed Huerta as a ‘jackal’ who had stolen the Presidency.

In March of 1913, Pancho Villa returned to Mexico intent on avenging the murder of Madero and relieving his country of the tyranny of Huerta. He later recalled . . .

That night I had eight men with me, and we had no definite plan but had decided to make for my old haunts in the Sierra Madre mountains, where I knew I could find men to follow me. We had one sack of flour, two small packages of coffee and some salt. That was all our food supply. Of course, we were all well armed, but had little ammunition.

Villa’s small band began making lightning raids upon the Federal forces that were garrisoned in Northern Mexican towns and forts. Slowly the were able to accumulate the arms and supplies that they needed. Within a week, Villa’s band had grown to more than a hundred men and within three months it had morphed into a legitimate army of 18,000 troops.

In battle, Villa proved to be ruthless. His standard policy was to kill prisoners. A lucky few would only be spared by the intervention of his lieutenants. In contrast to this brutal side of his nature, though, Pancho had a strong social conscience. For two months in 1913, he held the position of Governor of Chihuahua. He expropriated land from the wealthy to distribute to the poor, opened several schools and enacted laws to protect widows and orphans. On Christmas Day, 1913, he gathered the poor of Chihuahua together and gave them each fifteen pesos. By such actions, he became the hero and savior of the underclass.

By early 1914, Villa had control over the northern part of Mexico. Handing over the governorship to his lieutenant, he began the march south to Mexico City where Huerta sat in the presidential chair. As he swept south, he conquered everything in his way, gaining a reputation as the Centaur of the North. By June his army had grown to 50,000, most of whom were on horseback. By now it was a fully-fledged army, with mobile hospitals and recruits from other countries, including the United States. At the head of this, the largest revolutionary army in the history of the Americas, stood Pancho Villa, a leader with great charisma who at the same earned the respect and fear of his men.

Villa developed a military strategy that proved enormously successful. Day and night, he would pour a continuous frontal assault against the enemy line, supported by cavalry troops. The attacks were continually rolling with troops at the front being replaced by those behind. This gave the defenders no time to rest, resulting in them almost always being overwhelmed by the sustained force of the attack.

Villa also established offices within his army similar to government departments. He had an office of foreign affairs, who were particularly focused on reaching out to President Woodrow Wilson for US aid. His financial committee made contact with wealthy landowners to assure them that they would be mistreated once victory was achieved.

The United States offered support to the revolutionary cause through a round-about means. Villa sold livestock and other products to the US, which provided the funds with which to purchase American weapons and ammunition. It was this flow of weaponry that enabled the rebel army to match up to the Federal forces.

In recognition of the aid being received from north of the border, Vila ensured that no American property was confiscated. Positive press in American media resulted, with the Washington Times reporting in January, 1914 about Villa that ’he is now carrying on a campaign of modern and humane warfare’. The media, in fact, fell in love with Villa, with one editor writing . . .

Villa is without the possibility of any doubt the greatest leader Mexico has ever had. His method fighting is astonishingly like Napoleon’s.

Villa instituted some telling innovations in Mexican warfare. He was the first to leave the women and children behind and force the pace of his army with raids, marching far away from his base. He would abandon his supply trains and head far out in search of the enemy. He was also the first to stage night time attacks, which became especially devastating to the enemy.

In the spring of 1914, the two key cities of Torreon and Zacatecas were taken. These victories brought the regime to its knees, with Huerta fleeing into exile on July, 14th, 1914. The Federal Army collapsed, leaving the revolutionaries to fill the vacuum.

Into the presidency now stepped Venustiano Carranza, a former hacienda owner who brought his forces into Mexico City ahead of Villa. Yet, it was Pancho Villa who was the hero of the revolution. Wherever he went, people would yell out ‘Viva Villa!’

Ousting Carranza

The struggle, however, was not yet over. Villa and his fellow revolutionary leader, Emiliano Zapata joined forces to oust Carranza, who they had never intended to take the helm. On December 6th, 1914, Villa rode at the head of 50,000 men, alongside Zapata with his 15,000. By then Carranza had already fled the capital.

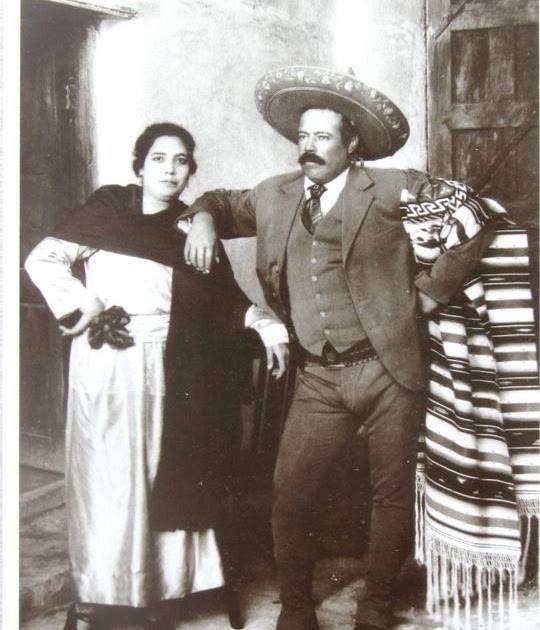

Pancho Villa was now at the height of his power. Wearing a navy blue suit and a cap with the eagle of the Mexican flag, he rode through the city as the masses turned out to shower him with praise. He went to the presidential palace and sat on the Presidential chair, but only long enough to have his picture taken. He never served as the President of Mexico, though he could have easily won an election at that time.

A council between the various fighting factions failed to bring a consensus and Villa continued to lead his army against pockets of rebellion. Alvaro Obregon was a supporter of Carranza who won a series of decisive battles against Villa’s army. Pancho was outsmarted by Obregon and many of his men were killed. He was forced to retreat to his base in the northern Sierra Madre mountains. In a few months of fierce fighting the invincible army that had marched into Mexico City had been reduced to a rag tag mob of just a few hundred men.

Violent Streak

A change now came over Pancho Villa. His violent streak was fully unleashed. In the time of San Pedro de la Cueva, he brought all of the men in town into the middle of the town and killed them all, personally shooting the local priest in the head. Then, in Santa Isabella, he shot several American miners.

The Americans now distanced themselves from Villa and recognized the reinstituted Carranza government.

At round 4 in the morning on the March 9th, 1916, Villa, incensed that President Wilson had legitimized the Carranza government, led a force of one hundred men across the border and into the town of Columbus, New Mexico. They attacked the town of 600 inhabitants from four directions, shooting indiscriminately, looting and burning buildings.

Villa, however, had chosen the wrong town. The 13th US Cavalry was stationed there, with 4 machine guns and 400 highly trained soldiers. The majority of his men were killed, but Villa managed to get away, leaving a trail of destruction in his wake.

The American response to the unprovoked Columbus attack as overwhelming. 10,000 troops were put on trains and sent to the border with the single objective of capturing the fugitive Pancho Villa. At the head of the American forces was John Pershing, who led his troops, along with Apache Indian scouts 350 miles across the border in search of Villa.

Into every village that he went, Pershing would yell out, ‘Where is Pancho Villa?’ Every time the locals would provide false information. On several occasions portions of Pershing’s army skirmished with Villa and his tiny band. On one occasion, Pancho was shot in the leg. In April, American newspapers reported that he had died as a result of the leg being infected.

The reality was that Villa was still very much alive, though badly wounded and hiding out in a cave in the Sierra Madres. Pershing’s expedition managed to capture weaponry and horses but failed in its objective of bringing Pancho in.

With the American’s having withdrawn, Villa reverted to his guerrilla fighting ways. He still had the support of the people and was determined to continue fighting against Carranza’s regime. Then, in 1920, with another coup in the offing, President Carranza was killed as he fled to the Gulf of Mexico with the national treasure.

Villa saw this turn of events as his opportunity to come to a peace settlement with the new regime. He rode for 13 days to the city of Sabinas, Coahuila and telegraphed new president Adolfo de la Huerta requesting an amnesty. Huerta agreed, grateful that the threat of a Villa overthrow was nullified.

Retirement and Death

Vila was given a 25,000 acre farm in Canutillo. He brought 200 of his men with him, who he immediately put to work on improving the run-down property. Within a short time, Canutillo was turned into a commune, with a school, wheat, corn and bean crops that were able to support a large community of people. Villa got up early each day to supervise the work and spend time in the school house. He hardly ever left the farm, fearful of assassination attempts.

On the morning of July 20th, 1923 Villa did leave his ranch. He went to Parral to visit one of his wives and to withdraw money to pay his workers. As his Dodge vehicle was driving through a deserted part of town, dozens of snipers opened up, filling the car with more than forty bullet holes, nine of which smashed into Pancho Villa’s body. His death was instantaneous.

Yet even in death, Villa did not find peace. Three years after his burial in Parral, his tomb was ransacked, the corpse removed and Pancho’s head cut off. Souvenir hunters had also taken pieces of the coffin and some of his bones. In 2010, the Wall Street Journal reported that his right index finger was being offered in a pawn shop in El Paso. The asking price was $9,500.

Sources:

Friedrich Katz: The Life & Times of Pancho Villa

Alejandro de Quesada; The Hunt or Pancho Villa

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pVWcgOcvgV0