It’s one of the greatest nations in the world. Germany is the lynchpin of the European Union, an economic powerhouse that’s also home to one of the world’s top creative capitals. Despite a history scarred by two world wars and 45 years of partition under a Communist dictatorship, it’s a nation that’s consistently been at the center of global affairs for 150 years. And it only exists because of one man.

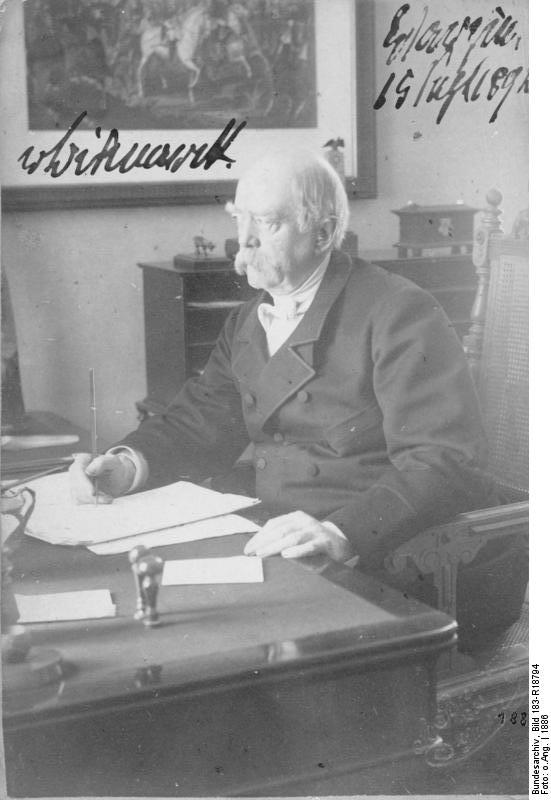

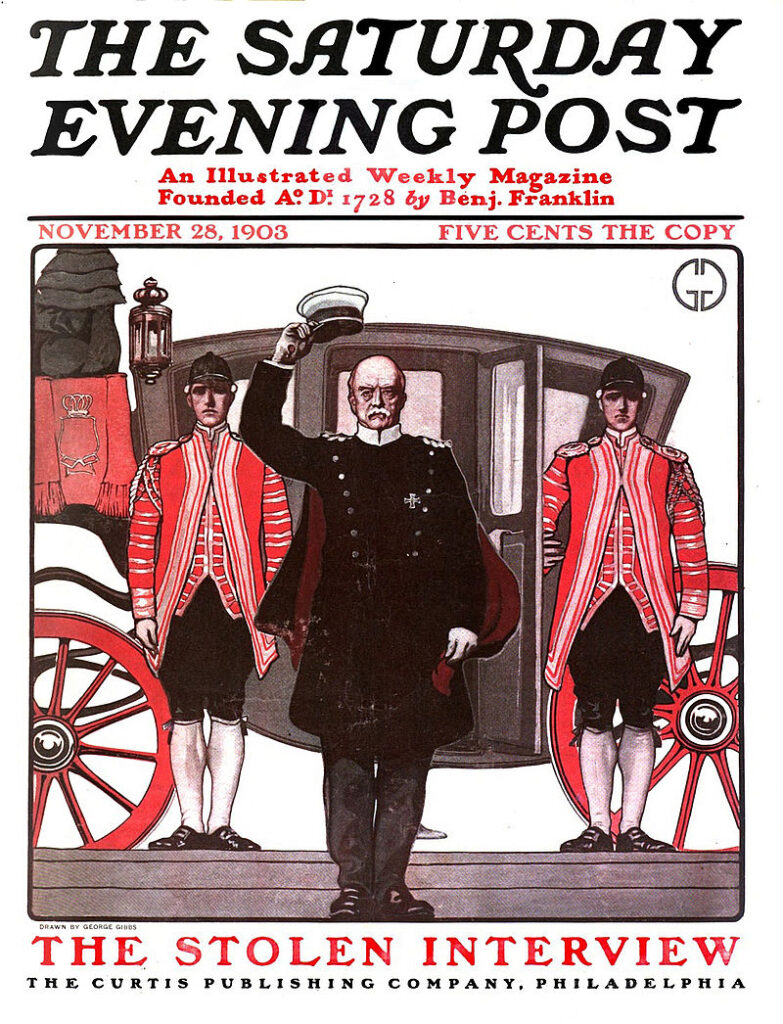

When Otto von Bismarck was born, Germany was a collection of 39 weak states cowering between the superpowers of France, Austria, and Russia. By the time he died, the German nation had been forged in blood and iron and Central Europe had a new sheriff in town. But while we all know the modern Germany he gave us, few of us know much about Bismarck himself. In this video, we take a look at the man known to history as the Iron Chancellor.

From the Ashes

When Otto von Bismarck was born in the Prussian village of Schönhausen on April 1, 1815, it was into a world that had been shattered by war.

Not ten years before, Napoleon’s Grand Army had come storming through Central Europe, destroying the Holy Roman Empire and leaving the Germanic states in ruins. Bismarck’s own home of Prussia had been deeply humiliated by a French military occupation.

Not that young Otto was aware of any of this. Less than three months after he was born, Napoleon was defeated at Waterloo.

For baby Otto, Napoleon’s defeat meant being able to grow up on his parent’s estate without war. That’s right: estate. Despite the image he’d later cultivate as a man of the people, Otto von Bismarck came from the Prussian nobility. His father was a Junker, a kind of minor aristocrat, while his mother came from a family of middle class professionals.

Still, money doesn’t equal comfort. Aged 7, Otto’s strict mother sent him away to school in the Prussian capital, Berlin, an experience Otto absolutely hated. He hated it so much, in fact, that it gave him a lifelong loathing of strong women like his mother.

While Otto was sulking in Berlin, Europe was trying to rebuild itself after Napoleon.

The destruction of the thousand year-old Holy Roman Empire had left a void in the center of the continent. To fill it, the surviving superpowers created something called the German Confederation, a collection of 39 states locked in loose association.

The Confederation was designed to be weak. Its power was balanced between the Catholic Austrian Empire in the south, and the Protestant kingdom of Prussia – where Otto von Bismarck was born – in the north.

As we run through Bismarck’s life, it’s important to remember there was nothing at this stage that even remotely resembled modern Germany. When you hear us say Bismarck studied in Hanover, it wasn’t like you moving from, say, Colorado to Washington. It was like literally moving to another country, albeit one where they spoke the same language.

This language thing is exactly why people would soon start wondering why there were 39 Germanic states instead of one united Germany.

But more on that in a moment. For now all you need to know is Otto entered Göttingen university in Hanover in the 1830s and studied to be a lawyer.

Remarkably for such a great man, he was useless as a student. His friends considered him a dandy, and his tutors considered him a drunk. He scraped through his course and joined the Prussian civil service, a terminally boring occupation. In fact, it was so boring that Bismarck wrote:

“the Prussian civil servant is like one musician in an orchestra… he’s confined to his own little part… I, however, want to make my own music.”

It’s a quote Bismarck fans are fond of, because it points to his future greatness. At the time though, that future greatness was very much in doubt. Bismarck actually quit the civil service in 1839 after his mother died and returned to his father’s estate. There he briefly became a Bible-thumping evangelical, before marrying the pious Johanna von Puttkamer and living as just another Prussian farmer.

The one notable thing he did came in 1847, when he was sent to the Prussian parliament and made a number of speeches attacking the nation’s Jews. At this stage, in his early 30s, he really was little more than a random hick from Pomerania.

You know the saying, “commeth the hour, commeth the man”? Well, no-one in 1847 Europe knew it, but the hour was very nearly upon them. And the man was already here.

Revolution!

In the library of European history, 1848 is the giant red volume simply titled “Whoa!”

On February 22, a French government ban against banquets led to a Paris uprising which deposed the king. Barely three weeks later, on March 12, a similar uprising in Vienna toppled Klemens von Metternich, the guy who’d been holding Europe together since Napoleon’s defeat.

It was a spread of revolution, a contagion of uprisings. And, after Metternich fell, nowhere was safe.

Within days, Berlin was paralyzed by riots which nearly brought down the conservative Prussian king, Friedrich Wilhelm IV. It was only by promising a slew of liberal reforms that Friedrich Wilhelm was able to cling onto power.

One of those reforms? People could now discuss the possibility of uniting Germany.

For a guy who’s famous for uniting Germany, you might be surprised to hear Otto von Bismarck wanted no part of this nationalist revolution. While Liberals in Prussia and the other German states were holding elections and creating a parliament to write a new, pan-German constitution, Bismarck was considering arming his peasants and marching on Berlin to preserve Prussian sovereignty.

In the end, though, Bismarck settled for using his position in the Prussian parliament to become one of the loudest anti-revolutionaries in Europe.

The thing you’ve gotta remember is that “Germany” had never been a thing before. For Bismarck, uniting all 39 states in the German Confederation meant turning his beloved, Protestant Prussia into a support player in a nation dominated by the Catholic Austrians.

On top of that, the guys now pushing to unite Germany were all middle class Liberals, while Bismarck was a reactionary, ultra-conservative aristocrat. He loved his king, he loved God, and he loved order. For Bismarck, 1848 must have been a living hell.

But that turbulent year did provide Bismarck with one important boost. It brought Bismarck firmly to Friedrich Wilhelm IV’s attention.

Throughout the revolution, Bismarck was one of the most pro-monarchy men in Prussia. Even when it seemed the old order was about to be swept away he clung stubbornly to the past, like a reactionary German limpet.

So when the forces of counterrevolution finally got control in 1849, Bismarck was perfectly placed to reap the rewards.

As the revolutions failed in Prussia, Austria, and elsewhere, thousands of German Liberals were forced to flee to America. By 1851, the old order had been completely restored. For his services to the Prussian crown, Bismarck was made ambassador to the city state of Frankfurt.

Of all the countries rocked by 1848, only one underwent permanent change. In France, where it had all kicked off, the old monarchist order was destroyed. In its place, a president rose up who’d soon become an emperor.

His name was Napoleon III, and if you’ve already seen our video on him, you’ll know he and Otto von Bismarck were destined to collide with enough force to reshape the continent.

Iron and Blood

On September 30, 1862, a giant of a man slowly lumbered to his feet in the Prussian parliament and delivered a speech that would change European history.

At 6ft4, and with a body built not unlike a particular type of brick outhouse, Otto von Bismarck was a presence that always commanded attention. But on this day, it was his words rather than his size or volcanic temper that set everyone talking.

In the 11 years since 1851, Bismarck had been serving as Friedrich Wilhelm’s ambassador to the capitals of Europe. He’d been in Frankfurt. St Petersburg. He’d even briefly been stationed in the court of Napoleon III in Paris. And being so close to the levers of power had given him time to think.

Slowly, Bismarck had come to realize that the world was changing whether he liked it or not. Men’s dreams of a united Germany hadn’t died with 1848. And the Catholic Austrians were ascendant in the German Confederation even without a union.

Either the Prussian giant stood by and watched the Liberals’ and Austrians’ dreams come true, or he beat them at their own game.

It was from these musings that Bismarck’s famous “Blood and Iron” speech sprang.

On that day, September 30, 1862, Bismarck was in a precarious position. Roughly a year before, Friedrich Wilhelm IV had died, and the Prussian crown had passed to his dull, dimwitted son Wilhelm I.

Before 12 months had passed, Wilhelm had accidentally sparked a crisis that nearly toppled his government. The short version is he needed tax rises that the Liberal-dominated Prussian parliament simply wasn’t willing to pass.

With it looking like another revolution might be on the cards, Wilhelm panicked and recalled his father’s old acolyte Bismarck from Paris to become Prussia’s Minister-President.

No-one expected Bismarck to last eight weeks. And now here he was, about to deliver his first major speech to a hostile parliament.

No-one could have predicted what a bombshell it would be.

In his booming, Germanic voice, Bismarck declared:

“The position of Prussia in Germany will not be determined by its liberalism but by its power.”

He went on to say:

“Not through speeches and majority decisions will the great questions of the day be decided—that was the great mistake of 1848 and 1849—but by iron and blood.”

For the first time here, we see Bismarck explicitly addressing the revolution of 1848 not as something horrific to be forgotten, but as something that was just done wrong.

Parliament had tried talking and building consensus and all it had done was make chaos. Now it was time to do it right, to unify Germany with force and iron and blood.

To be clear, iron didn’t just mean war. It meant rapid industrialization. It meant a Prussia that was building ships and bridges and railways so fast it’d catch up with Britain and France.

But, yes, it did also mean war. Nobody in the parliament knew it, but Bismarck was about embark on three great wars that would take Germany from 39 shattered states to a single behemoth under Prussian control.

For the Liberals in Parliament, “iron and blood” was the last thing they wanted to hear. They tried to force Wilhelm I to remove his new minister-president from power, even refusing to work with him when Bismarck began collecting new taxes without their approval.

Not that this bothered Bismarck. He’d returned to Prussia with a plan to forge Germany in his conservative, protestant image. And the wheels – forged from the strongest iron, naturally – were already in motion.

War

The British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston once remarked:

“Only three people have ever really understood the Schleswig-Holstein business—the Prince Consort, who is dead—a German professor, who has gone mad—and I, who have forgotten all about it.”

All of which is our way of saying you don’t need to worry about the super-complicated background to the Second Schleswig War. All you need to know is that Schleswig and Holstein were two regions on the border between the German Confederation and Denmark, and that on February 1, 1864, Bismarck convinced the Austrians to join him in invading them.

The Second Schleswig War is today seen as the beginning of the German Wars of Unification. More or less everything went according to Bismarck’s plan.

Prussia and Austria stomped Demark, occupied the peninsula, and within months had taken control of Schleswig-Holstein. Holstein went to Austria, while Schleswig went to Prussia.

In the 21st Century, it’s fashionable for historians to debate whether Bismarck really was a genius, or just extraordinarily lucky.

It’s certainly true that the Second Schleswig War was possible only thanks to a convenient succession crisis in Schleswig-Holstein. But the rest of it?

Austria had no beef with Schleswig-Holstein, they didn’t want to invade. But Bismarck managed to convince Vienna that not joining his war would make Prussia too powerful in the German Confederation. So join it Austria did, a move that cost them most of their allies – just as Bismarck wanted.

With Austria diplomatically isolated, Bismarck then checked in on his old frenemy, Napoleon III, to ask if Paris had any desire to protect Vienna. When Napoleon III was all like “nah, that’s cool dude,” Bismarck set about engineering his second major war.

In January, 1866, Bismarck found a pretext in Austria’s administration of Holstein. Again, the ins and outs don’t matter; what matters is that, by June, Austria and several German states, including Hannover, were ready for war with Prussia.

This was an exceptionally bad move.

The moment the starting gun fired on the Seven Weeks’ War, Prussia’s ultra-modern, ultra-efficient army was bulldozing its way across Central Europe, crushing everything in its path.

Seven weeks after the conflict exploded, the Austrian army had been utterly defeated.

Back in Berlin, Kaiser Wilhelm couldn’t believe his luck. He and his general staff could already envisage Prussian troops marching through Vienna.

But that never happened. Bismarck put his extremely heavy foot down. There would be no march on Vienna, no humiliating peace treaty for Austria.

All he wanted was to force Vienna to promise they’d never, ever join a united Germany. If they agreed, then any future Germany would naturally be dominated not by the Catholic Habsburgs, but by the protestant Prussians.

This practically gave Wilhelm a stroke. The Kaiser was so adamant Austria be crushed that Bismarck had to threaten to throw himself from a fourth floor window if Wilhelm gave the order to march on Vienna.

In the end, Bismarck’s theatrics carried the day. The Austrians agreed to leave this whole uniting Germany thing to Prussia, and Vienna was left standing.

Back in Berlin, the two wars had made Bismarck a hero. Even the Liberals who’d tried to get him fired now sang his praises. Their chorus only got louder when Bismarck annexed Schleswig and Holstein and Hanover, and forced every Germanic state north of the River Main into his new North German Confederation.

By July, 1867, those 39 Germanic states we started this video with had been reduced to just five. In the south, there were Bavaria, Baden, Württemberg, and Hesse-Darmstadt. In the north, Bismarck’s new, Prussian-dominated North German superstate straddled the Baltic Sea.

All that was needed now was some pretext for getting the southern states onboard this new thing called Germany. Luckily, Bismarck had plans for one final war.

Death of an Empire

For most in Europe, the creation of the North German Confederation was greeted with enthusiasm.

For Liberals and German nationalists, it was the moment they’d been waiting for since 1848. For the major powers, it was a useful corrective to the void left by the Holy Roman Empire’s destruction.

But there was one man who was very displeased with the way things were going.

In Paris, Napoleon III stewed in bitterness. Having given Bismarck his blessing to go to war with Austria, the French Emperor had been expecting something in return, and made moves to annex Luxembourg for France.

But Bismarck stopped him. Worse, he threatened to go to war over Luxembourg’s neutrality. Suddenly France was looking like the weak European power against this booming new nation of Germany.

So when a succession crisis blew up in Spain in 1870 and Prussia tried to step in, Napoleon III decided to assert his empire.

As you’ll know if you’ve watched our video on Napoleon III – and trust us, these two videos really complement one another – Paris dispatched the French ambassador to Ems, where he accosted a vacationing Kaiser Wilhelm I. The two had an argument and that was that.

Only it wasn’t quite. See, Bismarck somehow got hold of a memo about that argument. By now a master of the dark arts of politics, he subtly edited what had been said so it appeared French honor had been unforgivably insulted.

Known as the Ems Dispatch, Bismarck’s edited memo did it’s job perfectly. When Bismarck leaked its contents to the press, the French public was so outraged that Napoleon III declared war.

For the previous three years, Bismarck had been trying to cajole the southern Germanic states into joining his new confederation without success.

But with the French suddenly preparing to invade Prussia through those southern states, the holdout German rulers changed their tune. Terrified of a dollar store Napoleon rampaging through their backyards, Bavaria and the rest fled into Bismarck’s embrace.

Bismarck made it simple. His army would protect them from the French, on one condition. They join his new German Empire.

Once he had their agreements, Bismarck set out to crush the French.

The French had gone to war expecting the other European powers to join them. But Austria was now on good terms with Prussia over that whole “not invading Vienna” thing, while the Italians loved Prussia for giving Austria a kicking. Britain and Russia, meanwhile, simply didn’t care about a squabble between Paris and Berlin.

So when the threadbare French Army finally attacked the well-trained Prussian one, on August 4, 1870, it wasn’t even a rout. It was a massacre.

Over the next month, the Prussians humiliated the French. First they scattered their army. Then they invaded France. Then they laid siege to Paris.

Finally, on September 2, 1870, the Prussians surrounded and captured Napoleon III.

It was the death blow for the Second French Empire. It was also the birth of the German one.

On January 18, 1871, Bismarck and Wilhelm traveled to Louis XIV’s old palace of Versailles to declare the creation of the German Empire.

It was touch and go. At the last moment, Wilhelm decided he didn’t want to be Emperor but king, and it was only after another multi-hour screaming match that Bismarck convinced Wilhelm that if you don’t do this now, dum-dum, everything we’ve been working for this last decade will be lost!

Finally, though, the empire was declared. Beneath a ceiling fresco of Louis XIV invading the Holy Roman Empire, French representatives surrendered the territory of Alsace-Lorraine to Germany, and agreed to pay an indemnity of five billion francs.

Not 20 kilometers away, Prussian bombs continued to fall onto the citizens of Paris, leaving them shell shocked in more ways than one. Almost a quarter of a century after the Liberal revolutionaries of 1848 had failed to do so with speeches, Bismarck had finally created Germany with blood and iron.

It was the dawning of a brave new world, and Europe would never be the same again.

Germany: Fatherland

If the 1860s were Bismarck’s decade of war, the 1870s and ‘80s were his decades of peace.

With France crippled and Germany suddenly a thing, the other powers sat at the table all started exchanging uneasy looks with one another, wondering if this new beer swilling nation was gonna start something.

But they needn’t have worried. Unlike Kasier Wilhelm II, or Hitler, or Napoleon, Bismarck was a conqueror who believed in restraint.

With the Franco-Prussian War over, he halted German expansion. Turned his attention to internal security. While future generations would assume Germany’s existence was a matter of destiny, Bismarck knew how fragile his new empire was.

Instead of fighting, now was the time for ruling.

As dual minister-president of Prussia and Chancellor of the new Germany, Bismarck ruled with a strange combination of enlightenment and repression.

On the enlightened side, he introduced universal male suffrage. Established a national healthcare system. Introduced accident insurance. Brought in old age pensions.

This was Europe’s very first modern welfare state, and it was complemented by enlightened acts on the world stage. In 1885, Bismarck hosted a great power conference that ended the scramble for Africa. He also devoted himself to European peace, going out of his way to accommodate Russia, England, Austria, Italy… even France.

But behind this enlightened statesman lay a guy who just couldn’t stop himself from occasionally acting like a petulant dictator.

In the early 1870s, for example, Bismarck launched a policy known as Kulturkampf. Dressed up – as these things usually are – as a way of preserving ‘native culture’, it was really just an excuse to crack down on German Catholics and try and turn them into good, Prussian-style Protestants.

This was followed, in turn, by a crack down on socialists and social democrats, and anyone basically to the left of Bismarck, which was basically everyone under 50.

Bismarck was terrified of exiting in his own revolution. So he assumed cracking down on the forces he feared would keep him in office forever.

But while Bismarck was never overthrown, he couldn’t keep his enemies out of government, either. When the election of 1890 rolled around, two decades of anti-Catholic, anti-socialist policies resulted in a landslide for the anti-Bismarck forces.

However, it was 1888 rather than 1890 that proved to be Bismarck’s undoing.

In German history, 1888 is known as The Year of the Three Emperors. That’s because, on March 9, Wilhelm I passed away, and Fredrick III became Emperor.

Bismarck had known for years that Wilhelm was on the way out, and had spent all that time grooming Frederick just as he had Frederick’s father. Unfortunately for Bismarck’s well-laid plans, Frederick III lasted just 99 days in office before dying himself.

In his wake, another man rose to the imperial throne. A man who would go down in history for the wrong reasons: Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Wilhelm II was everything Bismarck couldn’t stand. Impulsive, sulky, prone to absurd decisions and, most importantly, utterly unwilling to listen to a stuffy old windbag who’d served his grandfather and great-grandfather. Barely had Wilhelm II’s backside warmed the imperial throne than he publicly dismissed Bismarck in 1890.

The Iron Chancellor returned to his old estate in a huff, expecting the government to recall him at any moment. But they never did. Although he lived 8 more years, Bismarck would never be in a position of power again.

Death of a Blacksmith

If Bismarck’s life had been the great roar of an iron ox, his retirement was the bellowing of a wounded bull. Until his death, Bismarck wrote books and pamphlets and made speeches lionizing himself while tarring Wilhelm II and his government as a bunch of incompetent boobs.

While this was doubtless cheering to his supporters, it laid an unfortunate precedent.

Bismarck’s self-mythologizing rants cemented the image of Bismarck the blacksmith, single-handedly forging Germany’s destiny. It was an idea that hung around in German politics into the mid-20th Century, influencing another self-proclaimed man of destiny: Adolf Hitler.

Unfortunate, too, was the way Bismarck simply ranted, rather than teach. In his life, he’d created a complex system of alliances and friendship to ensure no other power tried to attack Germany. But the system was so complex that no-one else could really grasp it. And so his departure marked the beginning of the slippery slope to WWI.

Finally, on July 30, 1898, Bismarck passed away. In his last moments, he expressed regret that he hadn’t been kinder to his dog, Sultan, before saying that he’d soon see his wife Johanna again. He was 83.

From our modern perspective, it’s impossible to overstate how important Bismarck was. He managed to take a group of disparate European states and transform them into a single, united whole.

It’s telling that, even in the wake of WWI and then WWII, no-one ever seriously considered breaking Germany back up again. Even the creation of Communist East Germany ended with the two Germanys reuniting in 1990. Modern Germany may be smaller than it was in Bismarck’s day, but it’s continued existence is now a geopolitical given.

Can we imagine a world without Bismarck? Certainly, it would look very different from our world today. Berlin would be a backwater, the European Union likely wouldn’t exist, and Germany would just be a crazy dream some wayward Liberals had once, back in 1848.

On the other hand, we’d have had no WWI. No WWII. No Hitler, or Goebbels, or the Final Solution. Would it be a better world? This far removed, all we can say is that it’d be unrecognizable.

Those who followed Bismarck may have used his creation for evil ends, but there’s no doubting the Iron Chancellor himself was a great man of history. Bismarck once said he wanted to make his own music on the world stage. Even now, over 120 years after his death, we’re still all singing from his hymn sheet.

(Ends).

Sources:

NOTE: We should link to our Napoleon III video as a source.

(Two excellent podcasts on Bismarck’s life and achievements): https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00775pm

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b04k6sd7

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Otto-von-Bismarck

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/mar/19/bismarck-life-jonathan-steinberg-review

https://www.historyextra.com/period/bismarck-a-life/

https://www.history.com/topics/germany/otto-von-bismarck

Second Schleswig War of 1864: https://www.britannica.com/event/German-Danish-War

Seven weeks’ war of 1866: https://www.britannica.com/event/Seven-Weeks-War

1848 revolutions timeline: https://www.preceden.com/timelines/46791-the-revolutions-of-1848

Map of North German Confederation: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_German_Confederation#/media/File:Map-NDB.svg

Random bit – only known recording of Bismarck’s voice, made on wax cylinder in 1889, just before he died. Rediscovered in 2012: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1889_recording_by_Otto_von_Bismarck.ogg

History of Prussia: https://www.britannica.com/place/Prussia/media/480893/194371

Blood and Iron speech: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blood_and_Iron_(speech)