By Arnaldo Teodorani

It’s the 1st of October, 1938. Heston airport, just outside London. A man steps out of a propeller airplane to address a crowd of journalists, officials and onlookers. He waves in triumph a piece of paper carrying two signatures, his and the one for a certain Mr A. Hitler. The man is hailed as a hero, as he announces that he has truly achieved “peace for our times”.

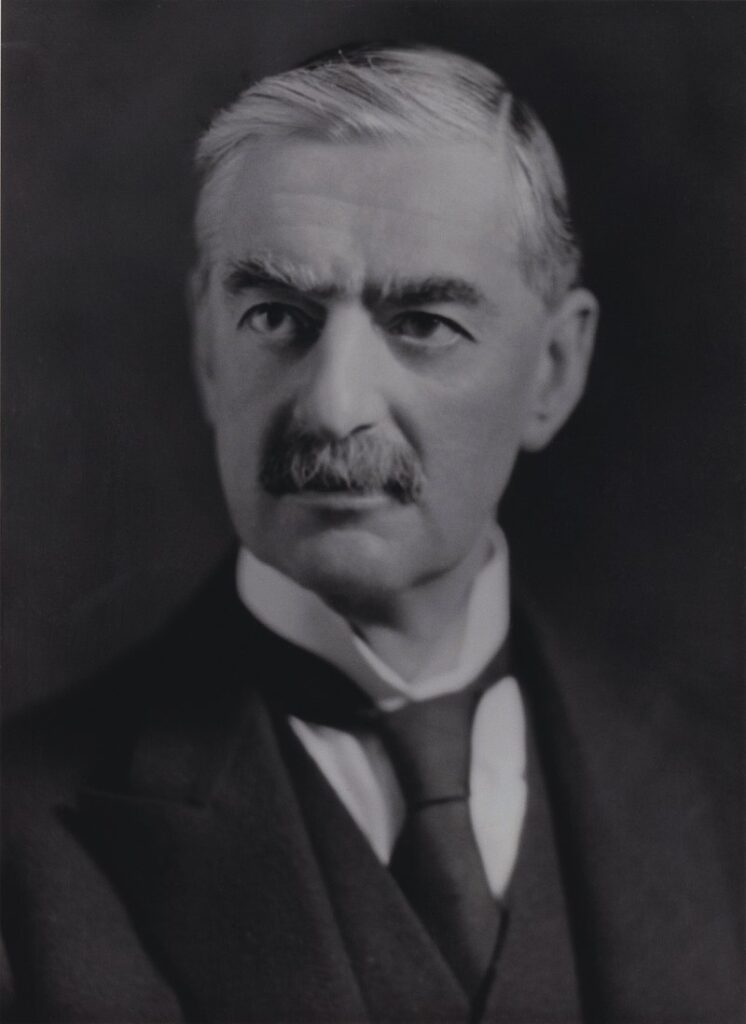

This man, whose status as a hero will soon be critiqued by none other than Winston Churchill, is the current British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain. He has just signed an agreement with the German government, preventing war in Europe – at least for the moment – but sacrificing the young State of Czechoslovakia to Nazi demands.

Neville Chamberlain has become synonymous with the ill-advised policy of Appeasement, an emblem of the West weakness when faced by the aggressive bullying of the Axis powers. But is that fame fully deserved?

From Birmingham to the Bahamas

Arthur Neville Chamberlain was born in Birmingham, England, on the 18th of March 1869, in a wealthy, politically involved family, although they were not part of the aristocracy. His father Joseph was a Cabinet Minister during Queen Victoria’s reign who had married twice having a total of six children. Beatrice and Austen, from a previous marriage, and then Neville and three daughters, Ethel, Ida and Hilda, from his second wife.

As it was tradition at that time, it was down to the boys to perpetuate the trade and traditions of the family. Austen, Neville’s older half-brother, was the one to initially carry out the political ambitions of the Chamberlains. He took up a string of civil service and political posts, culminating his career as Foreign Secretary in the 1920s. He was the mastermind behind the Treaty of Locarno between Great Britain, France, Weimar Germany, Italy and Belgium which earned him a Nobel Peace Prize.

Neville, on the other hand, was expected to take the reins of the family’s many business enterprises. He perfected his education first at the Rugby School and then at Mason College, now the University of Birmingham. Coming from a privileged family does not guarantee happiness, though, and it was reported that Neville was an introverted, shy boy, whose school years were plagued by incidents of bullying

After his formative years, aged only 21, Neville was tasked by his father to manage one of the Chamberlain’s business enterprises. A daunting prospect for anyone, but the task may have been made lighter by the fact that the job involved managing a plantation. In the Bahamas (ref BBC)!

That must have been fun for young Neville, unfortunately after some years that business venture ultimately failed. Neville had anyhow proven himself to be a talented manager and supervisor. After returning to England he would put that experience to successful use, first in the private sector, and then following Austen’s footsteps into politics.

Going into Public Service

In 1911 Neville Chamberlain secured his first political post by winning a seat in the Birmingham City Council. In the same year he married Anne Vere Cole, with whom he would later have two children, Dorothy and Francis.

Chamberlain’s next step was to secure a higher position in local politics, which he did by becoming Lord Mayor of Birmingham in 1915. By now aged 49, he was too old to serve in WWI, but he did contribute to the war effort as Director of the National Service, an appointment awarded directly by Prime Minister Lloyd George.

This job involved ‘compulsion’, which is basically the equivalent of conscription for war industries. However all of Chamberlain’s attempts to drive compulsory labour into industries vital to the war effort were hampered by the unions, by the war cabinet or Lloyd George himself. Apparently the two men could not stand each other. After Chamberlain finally resigned in August 1917, Lloyd George wrote to his family

“Chamberlain has resigned, and thank God for that”

While Chamberlain referred to the Prime Minister as

“that dirty little Welsh attorney”.

This experience almost deterred him to stay clear of politics, but he made a comeback into public life by winning a seat in the House of Commons in 1918 as a member of the Conservative Party. From then on, his career was on the rise.

In 1922 he became Postmaster General in Andrew Bonar Law’s government, a test that he passed with flying colours, becoming Minister of Health within months and, shortly afterwards, Chancellor of the Exchequer. All in little more than a year, and within 5 years of entering Parliament. By the way, for those not familiar with the workings of the British Government, the Chancellor of the Exchequer is the Secretary or Minister in charge of the Economy. So, it is a big deal.

Chamberlain retained this post for the following years, and did very well. In 1929 he reformed the so called “Poor Law”, which laid down the foundations of the welfare state. In the crisis that followed the Wall Street Crash he protected the fragile state of British industry by passing the Import Duties Bill, in 1932.

All this hard work paid off when in May 1937 Neville Chamberlain was elected leader of the Conservative Party and succeeded Stanley Baldwin as Prime Minister. His early efforts were a continuation of his welfare reforms. For example, the Factories Act of 1937 restricted the number of hours that children and women worked. And in 1938 Chamberlain supported the Holiday with Pay Act, which gave workers a week off with pay.

By looking at his career so far you could see how the shy boy from Rugby School had turned into an active, ambitious leader willing to bring about improvements to the society around him by breaking up with established traditions (ref BBC).

However, his achievements on the domestic front were to be overshadowed by a looming crisis in a faraway land, of which people knew nothing about, to use his own words.

The Sudetenland Crisis

Right, I am not going to chart here the rise of Hitler and the Nazi party and how the new German government immediately started making plans for territorial annexations. I’ll actually tell you more about this later.

So, let’s scroll our Google maps south of Berlin instead and look at the Sudetenland region instead. This is a region in then Czechoslovakia which bordered with Germany and was home to some 3 Million ethnic Germans.

Back in 1931 a Sudeten German called Konrad Henlein had founded the Sudeten Germans People Party, which advocated for the region to secede and be annexed to Germany. Needless to say, in the following decade, Nazi leadership had openly supported Henlein’s cause.

Sure, Germans on both side of the Czechoslovak border wanted to be reunited, but the push for annexations had far more materialistic reasons which worried the Government in Prague. The Sudetenland region was home to lignite and coal mines. It was also the most heavily defended, meaning a peaceful annexation to Germany would have granted a convenient stepping stone to annex the whole of Czechoslovakia.

Why would Nazi Germany be so interested in absorbing that small, young, central European state? Skoda. These guys now manufacture affordable city cars, but back then the Skoda works were one of the largest armament manufacturers in Europe. The production volume of Skoda Works between August 1938 and September 1939 alone was nearly equal to that of all British arsenal factories in that period. And sorry to jump ahead, but in 1939 a certain Hermann Goering made a nice little profit by acquiring shares in Skoda.

So, I am going to venture a personal observation and say that Nazi leadership main interest was not the well-being of Konrad Heinlein and the Sudeten Germans, but rather to replenish their arsenals and their pockets.

But back to the crisis.

In late summer 1938 the Nazi party asked Heinlein to stir some trouble, as a means to create an excuse for a military intervention. The government of Eduard Benes in Prague had created a system of defensive alliance with France and the Soviet Union, but neither of them was really keen to intervene should an invasion occur.

Chamberlain was well aware that if France did intervene, also Britain would be dragged into a European war, which not only himself, but his whole cabinet and the majority of the public opinion were keen to avoid at all costs.

The British Prime Minister then took the initiative to lead a series of negotiations throughout September 1938 to prevent an armed conflict.

The first meeting with Hitler took place at Berchtesgaden, near Munich. At this meeting Hitler demanded that the Sudetenland should be handed over to Germany. Without consulting Eduard Benes, Chamberlain agreed that those areas containing more than 50% Germans within them should be handed back to Germany. Chamberlain managed to get the Czechs and the French to agree to this solution.

On September 22nd, Chamberlain flew again to Germany, in Bad Godesberg to meet Hitler so that the final details of the plan could be worked out. Hitler had a very low opinion of Chamberlain, describing him in private as

So it was not surprise that the Fuhrer stunned the Prime Minister with a whole set of new demands:

Number 1 – German troops were to occupy the Sudetenland.

Number 2 – Czech lands containing a majority of Poles and Hungarians should be returned to Poland and Hungary.

Effectively, Hitler was demanding for a dissolution of Czechoslovakia.

This time Chamberlain and French President Daladier rejected these demands.

The stalemate was unblocked by Benito Mussolini. He proposed an emergency conference in Munich to reach an agreement once and for all. The participants were

Germany [names of countries appear on screen with a ping]

Great Britain

France

Italy

Can you spot the missing guest? You are right: Czechoslovakia was not. And neither was the Soviet Union, which pissed off Joseph Stalin.

Without consulting the Czechs, the four powers agreed that the Sudetenland should be given to Germany immediately. The governments of Britain and France made it clear to the Czechs that if they rejected this solution, they would have to fight Germany by themselves.

This was the crowning moment of the policy of Appeasement.

On October the 1st 1938, German troops occupied the Sudetenland. Polish and Hungarian troops also occupied areas of Czechoslovakia which contained a majority of Poles and Magyars. The dismemberment of Czechoslovakia was complete when Germany formally annexed what is today the Czech Republic in March 1939, while Slovakia seceded and became an Axis ally.

Let’s return now to our initial scene: Chamberlain waving his newly signed agreement at the Heston airport. To him, a formal guarantee of “peace for our time” in Europe. To Hitler, just a

“scrap of paper”.

Did Chamberlain take the right decision?

It is easy to say, with the power of hindsight that Chamberlain’s decision was a completely wrong one.

On a moral level, the Western powers, as members of the League of Nations and allied of Czechoslovakia had a duty to step in and protect an allied country – or other member States – from

aggressions and demands worthy of a schoolyard bully.

On a practical level … the matter is more complicated, but it also weighs against Chamberlain. Now, the assumption that Britain and France were not ready for a full-scale war, especially with Germany, may have been correct. And it is understandable that Chamberlain and Daladier were keen to avoid at all cost another carnage like the one brought about by WWI. The British Prime Minister had a particular fear of what destruction on civilian targets could be caused by the new tactics of war from the air. It seems that upon returning from his first flight to Munich, he observed how easy would have been for a bomber to hit at the heart of London. One of his military advisers even told him that two months of bombing raids would have caused one million victims.

But. But! Germany itself was not yet ready for a war with the West in the Autumn of 1938, the Wehrmacht being much weaker than it appeared from Goebbels’ propaganda reels.

A full mechanization of the Heer, or land forces, on the basis of General Guderian’s doctrine were still on the horizon. More importantly, the high echelons of the armed forces were not a united front supporting the Nazi party. It is reported in fact that the Army Chief of Staff, General Franz Halder was planning to eliminate Hitler and even carried a loaded gun with him at all times, should the occasion arise.

In September and October of 1938 the German High Command was fully aware of the country’s relative weakness and did not welcome the prospect of a war with Czechoslovakia, even if Britain and France did not come to the rescue. Czechoslovakia may have been a small country, but its army was well trained, well equipped and well defended by fortifications.

Did Chamberlain know all this? Apparently he did receive a report from MI5 detailing Halder’s plans, but would that have been enough to change the opinion of Chamberlain and of the majority of the Cabinet? More importantly, would that have been enough to change the course of eight years of Foreign Policy dedicated to appeasement?

A brief history of Appeasement

Neville Chamberlain became synonymous with Appeaser, but certainly he wasn’t the first political leader, neither in Great Britain nor elsewhere, to pursue a policy of appeasement in the face of military threat and aggression. Are you ready for a brief history of appeasement? Let’s start then!

Round one – Japanese invasion of Manchuria. In 1931 an explosion on the South Manchuria railway gave the Japanese military the perfect excuse to invade this Chinese region, to protect Japanese interests in the area. It was all part of a plan of aggression to expand Tokyo’s sphere of influence, provide an outlet for the booming population and provide new markets for a struggling industrial sector. The League of Nations’ intervention was initially bent on economic sanctions, which Britain and France did not endorse, fearsome of losing trade with Japan or even provoking a full-scale invasion of British colonies in the Far East. The result? A weak plan to create a semi-independent state in Manchuria, which Japan rejected by quitting the League of Nations and going on to complete the invasion of the region and establishing the puppet state of Manchukuo.

Round two! – Failed Anschluss attempt, 1934. Not one year in power and Hitler and the Nazi government were already bent on annexing Austria. Their plans kicked off with an attempted coup carried out by Austrian Nazis, which were obviously funded and directed by Berlin. The conspirators even managed to assassinate Prime Minister Dollfuss and the German troops were ready to move in. The Western powers, again did not intervene. Who, of all people, put an end to this first go at Anschluss? You may be surprised: Benito Mussolini, who at this time was not yet allied to Germany and was instead tied to Vienna by a protective treaty. Mussolini deployed two Alpine troops divisions on the Austrian border and the still-weak Wehrmacht had to hit the brakes.

Round three! – Italy invades Ethiopia, 1935. Yesterday, the defender, today the attacker: a border incident with Ethiopia gave Mussolini the excuse to order an invasion of Ethiopia in October 1935. British public opinion was in favour to intervene against Fascist Italy. It would have been dead easy: just shutting down the Suez Canal to Italian shipping would have put an end to the invasion. But Prime Minister Baldwin did not want to alienate Mussolini and his anti-German stance. Any intervention was delegated to the League of Nations. While negotiations dragged on into 1936, the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa fell in May 1936.

Round four. Hitler retakes the Rhineland, March 1936. The Rhineland includes the border areas with the Low Countries which were meant to stay de-militarised as per the Treaty of Versailles. But taking advantage of the Ethiopian crisis, the Germany army just up and went! They took a huge gamble, by the way. The marching units carried rifles loaded with blanks and had strict orders to retreat immediately at the slightest sign of Franco-British resistance. But resistance did not materialise, the occupation was carried out and Germany gained a huge advantage in preparation for the War to come.

Round six. Japan invades the rest of China, 1937. What started as minor clashes between the Imperial Japanese Army and the Chinese nationalist forces in July of that year quickly escalated into a full-blown invasion. As usual, the Western powers, the Soviet Union and the League of Nations looked on, while the Japanese carried out indiscriminate bombing of civilian targets. Interestingly, help for Chiang Kai-Shek’s Chinese nationalist army came from Nazi Germany, in the shape of training and supplies.

Round seven. The successful Anschluss in March 1938. When Germany incorporated Austria, the West remained silent and Italy was now on the side of the invader. By now Chamberlain had replaced Baldwin as Prime Minister, and as you may have guessed, he simply continued with the same policy put in practice by his predecessors and fellow member states in the League of Nations. In addition to the desire of avoiding a major war on the continent, Chamberlain was also motivated by “compensating” Germany in some way for the harsh treatment imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. Moreover, one of the key principles of the post-WWI world order was self-determination. Based on that principle, wasn’t it lawful to allow German minorities to reunite with their motherland? And now for the …

Bonus round! – The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. We could talk for hours on end about this war, but I’ll make just one point. Italy, Germany and the Soviet Union all intervened heavily, supporting opposing factions with troops, weapons and money. On the other hand, Britain and France simply forbid the supply of arms to either side. This non-interventionist policy was a continuation of Baldwin’s plan not to alienate Mussolini’s sympathies. Yeah, it worked a treat (!).

From Appeasement to World War II

And now let’s zoom back to London, and fast forward to the 3rd of September 1939. Neville Chamberlain has just announced on the radio that Great Britain is now at war with Germany. All his efforts to maintain peace in Europe, were all vain in the end.

Chamberlain’s leadership during the war is generally remembered as lacklustre at best and lacking in initiative, being these the months of the so called ‘Phoney War’, in which French and British troops did little but stand by the Maginot line, waiting for a German attack.

However it is fair to recognise one important victory which can be attributed to Chamberlain’s foresight: the Battle of Britain, or the months long duel in which the Royal Air Force established air superiority over the Luftwaffe, thus preventing Operation Sea Lion, the invasion of Great Britain. In the months after the Munich Treaty, Chamberlain led the development of Britain’s air defence systems, the more sophisticated in Europe: it was thanks to him that the Royal Air Force could rely on the revolutionary invention of RADAR to coordinate wave after wave of Spitfire fighter planes against incoming German squadrons.

But Neville Chamberlain could not reap the reward for such a success. On the 10th of May 1940, after a failed attempt to reclaim Norway from Nazi occupation, Chamberlain resigned. Winston Churchill – the main architect of the Norwegian debacle – became the new Prime Minister.

Chamberlain continue to serve in Churchill’s cabinet, but resigned for good in October 1940, too ill with late stage bowel cancer. Not one month later, on the 9th of November, Chamberlain died in his estate near Reading, in southern England.

Final words

As you have heard, it is too easy to dismiss Neville Chamberlain as gullible and naïve appeaser, who did not respond to Hitler’s provocations for all the wrong reasons. The reality was far more complex and it is understandable how Appeasement may have been considered as the best option at that time. However, Chamberlain had a record for breaking away with established policies and had he listened to other opinions rather than the Conservative majority, he could have changed the course of history for the better.

“You were given the choice between war and dishonour. You chose dishonour, and you will have war”