It was August 1856, and some miners were excavating limestone in the Feldhofer caves in the Neander Valley near Düsseldorf, just like their predecessors had been doing for centuries. During the dig, the workers unearthed some bones. No big deal, they thought, probably just a bear or something, so they discarded the bones with the rest of the debris.

One of history’s greatest discoveries was almost confined to the garbage dump, but fortunately, the mine’s owner, Wilhelm Beckershoff, saw the bones and was intrigued by them. His instincts told him that there might be something to them other than just being the remains of an animal, so he took them to the closest thing to a scientist that he could find – a local schoolteacher who was an amateur fossil collector in his spare time by the name of Johann Carl Fuhlrott. To his credit, Fuhlrott could immediately tell from examining the skullcap that he was looking at something special. It looked human, but not…too human. The low forehead, the prominent brow ridges, the sturdy bones; they all suggested that this was a different kind of person.

But still, let’s not get carried away. After all, Fuhlrott was a schoolteacher, not exactly an expert in the field. So he packed up the bones and traveled to Bonn, where he consulted with a professor of anatomy named Hermann Schaaffhausen, and he confirmed what Fuhlrott suspected – that they were looking at the remains of a primitive type of human. The Neanderthal had been discovered.

Origins

The duo did not immediately go public with their discovery. After all, as far as the entire world was concerned, this would have been the first-ever fossil of an archaic human. It wasn’t the kind of thing you just casually announced like next week’s cafeteria menu.

The pair made the announcement in 1857 and published their findings a year later, but they were not taken seriously by the scientific community at large. As we said, no other remains of extinct human species had been found by this point. It was even a few years before Charles Darwin published his seminal work “On the Origin of Species,” and evolution was hardly a widely-held view in scholarly circles. The unusual traits of the skullcap were dismissed simply as malformations belonging to a diseased, but otherwise unremarkable human.

Fuhlrott and Schaaffhausen needed two things in order to gain scientific approval. One was recognition from a more eminent figure in the field, and they got it in the form of renowned Scottish geologist Charles Lyell, who examined the bones and concluded that they were of a very old age. And the other was more fossils. If these remains truly belonged to a primitive species of human, then there should be others around, right?

Well, as it turned out, not only were there other fossils, but they had already been discovered – bones belonging to two different skeletons had been found in Belgium, while an intact skull had been recovered in Gibraltar decades earlier. However, it seemed that none of them had a local schoolteacher who dabbled in collecting fossils, so there was nobody to recognize the importance of the finds. Even so, with all this talk of a new species of human, people remembered that they had these fossils just sitting there, collecting dust, and brought them out for a closer inspection. These remains were also intriguingly distinct from those of modern humans.

Slowly but surely, the idea that we might be talking about an archaic type of human, distinct from Homo sapiens, was gathering steam. Finally, in 1864, the fossils were recognized for what they truly were – the remains of a different species of human. It was even given a name – Homo neanderthalensis.

As you could probably tell, the species was named after the German valley where the fossil of Neanderthal 1, as he came to be known, was found. Technically, the bones in Belgium were the first to be discovered, but since Neanderthal 1 was the one who kicked off the whole hullabaloo, it was decided that he would become the type specimen for his species. And with that, the field of paleoanthropology was born.

Anatomy

The study of Neanderthals has been going on for over a century and a half, and it is still very much a continuing process. As a general rule, we are not going to go over each individual discovery and advancement and place them chronologically because that would only make things more confusing. And now that we’ve said that, let’s immediately break that rule by looking at what happened in the years following the establishment of Neanderthal 1 as a separate human species.

Over the next few decades, more remains of Neanderthals were discovered, mainly in Europe, but also in Southwest Asia. Even so, not everyone was on board the whole “extinct human species” train yet, and some prominent scholars delayed the study of Neanderthals by arguing that the bones they kept finding simply belonged to diseased and deformed Homo sapiens. Mildly interesting, sure, but hardly something to revolutionize our understanding of humanity. Foremost German pathologist Rudolf Virchow was particularly guilty of this faulty reasoning, as he was convinced that rickets and arthritis were responsible for the physical deformities of the Neanderthal remains.

With that in mind, the opposite camp, which argued that Neanderthals were, indeed, a distinct and extinct species of primitive humans, received a giant boost to strengthen their case in 1908 when they discovered La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1, better known simply as “the Old Man.” As its name suggests, it was found in La Chapelle-aux-Saints, a commune in central France, and it was the first almost-complete Neanderthal skeleton ever discovered. The skull, in particular, was a real find, as it prominently displayed the heavy brow ridges, protruding midface, and low, receding forehead that is typical of the species.

The remains were around 60,000 years old, but the actual age of the Old Man when he died is still a “bone” of contention. Some say he was around 40 years old, while others argue that he was much older since the bone along the gums had time to re-grow after he lost several teeth, something that would have taken decades. Some scholars even speculate that the condition of the Old Man’s teeth made it impossible for him to chew his own food and that someone else probably ground it up for him. They saw it as the first sign that Neanderthals were not quite as primitive as initially thought and that they lived in an altruistic society where they helped and cared for each other, but more on that later.

Unsurprisingly, the Old Man was a landmark moment in our understanding of Neanderthals, but at the same time, it also created a common misconception that goes on to this day. If we have to point the finger at someone, then we have to point it at Marcellin Boule, the French anthropologist who was the first to study the Old Man. He was the one who assembled the skeleton, but he didn’t make it look like a modern human, even though he really should have. In his mind, Neanderthals were brutish, dim-witted, primitive creatures more closely resembling gorillas than us, so he made the Old Man with a severely curved spine, a stooped stance with bent knees, forward flexed hips, and the head jutted forward. He even gave the reconstruction opposable toes like the great apes.

This is still how many people picture Neanderthals, and the image is pretty far removed from reality. The Old Man indeed suffered from severe osteoarthritis, which would have impacted his posture, but modern experts still believe that Boule should have known better and that he let his preconceptions cloud his judgment and affect his work.

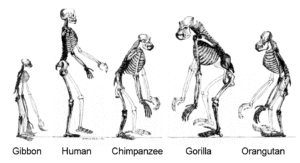

In reality, Neanderthals were physically quite similar to us. Recent research suggests that they even had the gene that causes red hair. On average, their bodies were shorter and stockier, they had larger noses and a distinct double-arched brow ridge, but many scholars argue that, if you were to bring a Neanderthal man into modern times, give him a shave and a haircut, and put him in a nice suit, most people would find him indistinguishable from any other person on the street.

We are only talking about physical traits that go skin-deep here. If you start to delve into the nitty-gritty of the Neanderthal anatomy, there are plenty of differences between our two species. Any bone expert could immediately tell if some remains belonged to a Neanderthal or a modern human by looking at the skull or the pelvis, which are noticeably different. Strangely enough, another reliable way of telling our species apart is the middle ear. The three tiny bones we have in there, which are vital in hearing, are more distinct between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals than they are between chimps and gorillas.

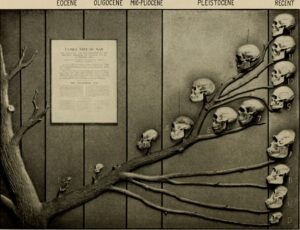

Evolution

Despite our extensive research into the origins and evolution of Homo neanderthalensis, it is still pretty much a vast and dark cave of knowledge into which we catch occasional glimpses of light. We should stress that a lot of this information is still not universally agreed upon, but it does represent our best understanding at the moment.

Contrary to what some people might think, Neanderthals are not our ancestors. They are more like a distant cousin. We did not descend from them, but rather both species evolved from the same ancient ancestor, maybe Homo heidelbergensis. They might also be the ancestor of a third hominid species called Denisovans, who have only been identified for the first time back in 2010, just to show you that major discoveries in paleoanthropology still happen regularly.

The divergence between our predecessors and Neanderthals might have happened sometime around 400,000 to 500,000 years ago but, as we already mentioned, not everyone is on board with this line of thinking. A group of scientists dropped an anthropological bombshell in 2016 when they announced they had recovered the oldest Neanderthal DNA in the world from some bones at Sima de los Huesos in Spain’s Atapuerca Mountains, dated to approximately 430,000 years ago. They wanted to push back the divergence of Neanderthals from their ancestor a few hundred thousand years. This would have made it too early for Homo heidelbergensis, but just right for yet another extinct species called Homo antecessor. So there is now a distinct group of scholars who believe that Homo antecessor was the last common ancestor between us and Neanderthals, not heidelbergensis. And the two sides get along about as well as the Jets and the Sharks so obviously, the only solution here is a choreographed street fight to determine the true common ancestor.

We might not be sure when Neanderthals first appeared, but we have a pretty good idea when they died out. It seems that their numbers started to plummet dramatically around 40,000 years ago, and very few traces of them have been found that are more recent than that. That being said, some pockets of Neanderthal civilization may have stuck around for a while, most significantly of all in Gibraltar. Proponents of this idea believe that Gorham’s Cave in Gibraltar was the last bastion of Neanderthal society and that our hominid cousins managed to survive there until 28,000 years ago before finally going extinct.

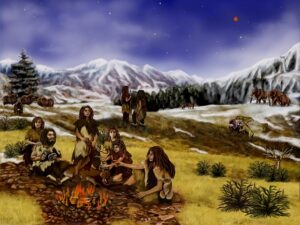

Their heyday, however, was around 100,000 years ago, give or take a few tens of thousands of years. They lived all over Eurasia, inhabiting regions stretching from England, going all over continental Europe into Central Asia, and as far east as Siberia. When our ancestors hopped over the Mediterranean Sea from Africa into Europe, the two groups collided, and yes, in case you were wondering, they did get freaky with each other. Most research seems to indicate that modern humans and Neanderthals interbred, which is why many people today still have a bit of Neanderthal DNA in their genetic code. This has its ups and downs. After mapping the human genome, we saw that this DNA is associated with skin and hair, possibly making us hairier and sturdier to survive colder climates, while also being involved in boosting our immune system. On the other hand, our Neanderthal DNA also seems to be associated with certain illnesses, such as diabetes, lupus, and Crohn’s disease.

Culture & Technology

Going all the way back to Marcellin Boule’s interpretation of Neanderthals which shaped our perception of our primitive cousin, we developed quite a low opinion of them. Basically, we looked at the Neanderthal as nothing but a hunched-over, grunting savage who was closer to an ape than he was to us, humans. But ever since then, most discoveries we’ve made about Neanderthals would suggest exactly the opposite – that they were intelligent and had a culture that was on par with that of our own hunter-gatherer ancestors.

Their brains, oddly enough, were bigger than ours in proportion to body size. But then again, so were the brains of ancient Homo sapiens, so that alone isn’t saying much. But Neanderthals got up to all the same stuff as our own ancestors. We know they liked to do a bit of painting, not just on cave walls but also in order to decorate their personal items. There’s a 36,000-year-old king scallop shell recovered from Cueva Antón in Spain that had been painted with red and yellow iron oxide minerals. This was before Homo sapiens came to the region, so it had to be the Neanderthals unless the bears in that area are particularly artistic. There also wasn’t any practical purpose to this, which meant that Neanderthals sometimes liked things just because they were pretty. The shell itself was probably used as a pendant. It wouldn’t be the only example we’ve found of modified jewelry.

Cave walls were, unsurprisingly, the Neanderthals’ favorite medium, although it seems that the primitive artist was more of an engraver than a painter. Dozens of such engravings have been found at Paleolithic sites all throughout Europe and the Middle East, all tentatively dated to a time before Homo sapiens came onto the scene. The oldest one of all is approximately 57,000 years old and was found in France’s Loire Valley. It was only announced a short while ago, in June 2023, once again, showing us that new developments are always happening in the study of our long-lost cousins.

If we are willing to wade into murky waters for a bit, we could make the highly controversial and still-doubtful statement that Neanderthals even had a musical side to them. Scholars have found multiple bone flutes which are tens of thousands of years old and the debate rages on over whether they were made by Neanderthals or Homo sapiens. One flute, in particular, known as the Divje Babe flute, is said to be up to 60,000 years old. It was unearthed in Slovenia in 1995, and it is made out of the thighbone of a cave bear. If its age is correct, then not only would it be undoubtedly of Neanderthal origin, since our ancestors hadn’t made it to Slovenia yet, but it would also be the oldest musical instrument in the world. But as we said, this is a hot take that is sure to rabble-rouse the scientific community.

Their crafting skills were also up to snuff. We have recovered all sorts of Neanderthal tools and weapons, ranging from precision tools like small blades and scrapers to medium-sized hand axes to large spears used for hunting. Stone was their main material, unsurprisingly, but they also dabbled in woodworking, processed animal hides for clothing, and also used organic tools such as shells and pumice stones. One particularly interesting discovery in a cave in Israel suggested that they might have even recycled tortoise shells to use as containers.

The one thing that Neanderthals did not do is develop long-range weapons. All signs indicate that their hunters liked to get up close and personal with their prey, even when they were taking on big game like mammoths and bears. They preferred to grip a large, thrusting spear with a lot of power behind it instead of something more versatile. They might have made smaller spears that could have been thrown, but definitely no bows & arrows. And nowadays, some researchers believe this could have contributed to their eventual extinction. Once modern humans came along and the two groups began competing for the same resources, our use of bows and arrows made us more successful hunters and left less food for our Neanderthal cousins.

We arrive now at one of the most contentious points in regard to the study of Neanderthals, not that anything we’ve said so far has been a slam dunk – funeral rites. We know that Neanderthals did intentionally bury their dead, at least on rare occasions, but was there any kind of symbolic or religious meaning behind it? Was there some kind of ceremony, or did they just dig a hole and chuck them in?

For decades, it has been suggested that Neanderthal burials were simply practical, if they could be bothered to do them at all. This was in line with the common view of Neanderthals as primitive and animalistic, but one cave in Iraq might change all of that. It is called Shanidar Cave, and it has been an absolute godsend for anthropologists for over half a century, thanks to the many remains and artifacts recovered at the site. But this recent find might be the biggest of all. It is the skeleton of a Neanderthal man that had been subjected to a so-called “flower burial.” Clusters of pollen were found in the soil he was buried in, suggesting that others threw flowers into his grave. This would be the first sign of any kind of funerary rite practiced by Neanderthals, but skeptics point out that the pollen could have come from burrowing rodents or insects, or even from the people excavating the site.

Extinction

Finally, we arrive at the big one – why did Neanderthals go extinct? And, to put it plainly, we don’t know. Scientists have been researching this answer for decades, and we are still nowhere near a consensus.

Obviously, the strongest inclination is to blame us humans for wiping out the Neanderthals. Unfortunately, we do tend to be pretty good at that sort of thing. And the timeline also lines up. Neanderthals lived in Eurasia for hundreds of thousands of years, and then 40,000 years ago, just poof! Whether or not they still survived in small pockets is up for debate, but they certainly disappeared from the vast majority of their habitat and, coincidentally, this just happened around the same time that Homo sapiens crossed into Europe from Africa. We outcompeted them for food, resources, and shelter; we could have brought along some fancy new diseases that they had no immunity towards, or we could simply have fought and killed them. And it could have also been a nice little mix of all three, but the end result was the same – score another win for Homo sapiens.

One recent hypothesis proposes the exact opposite – it says that Neanderthals died out because they made love, not war. Specifically, it argues that interbreeding with Homo sapiens on a large scale is what eroded Neanderthal populations to the point of extinction. This goes against the current general consensus, which says that, although the two groups did “mingle” together from time to time, it was only a casual fling that would not have any serious effect on their population numbers.

This is very much a new and controversial idea, but there’s another one that’s been going around for a while, and it has picked up some steam. Instead of blaming us, this notion claims that climate change drove the Neanderthals’ extinction. Specifically, a thousand-year-long cold snap occurred in Central Europe around 40,000 years ago, which would have led to massive habitat degradation and fragmentation for the Neanderthals even before Homo sapiens made it out of Africa. The same model asserts that the cooling period did not affect the areas inhabited by our ancestors as severely, so when the two sides finally met, we already had a giant advantage going into it. By the time Homo sapiens made it to Europe, Neanderthal populations had already dwindled significantly, and those who were left were no match for our superior numbers and advanced technology.

These are the facts as best we know them. And even though we know more about Neanderthals than any other extinct species of hominids, the gaps in our knowledge are still so large you could land a jumbo jet in them. In a few decades or even a few years, many of them might not be true anymore, replaced with new ideas as our understanding of our extinct cousins keeps evolving.