Imagine, for a second, that aliens land tomorrow. Armed with futuristic weaponry, they take the world’s leaders hostage, turning them into mere puppets. They dismantle humanity’s great buildings, destroy all religion… and mass-execute anyone who disobeys them. If that sounds like speculative fiction, think again; a similar scenario already unfolded 500 years ago. In 1519, conquistadors led by Hernan Cortez landed on the edges of the Aztec Empire. Within a year, they’d captured the emperor, Montezuma II, and turned him into their unhappy puppet. Shortly after, the entire empire collapsed, torn apart by the arrival of the Europeans.

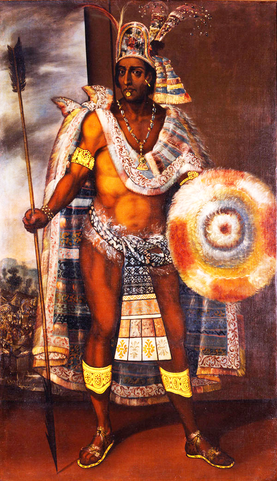

But while most of us know the tale of Cortez, how many know the story of the emperor he deposed? How many know what it must’ve felt like to be Montezuma, on the eve of his civilization’s collapse? Born into Aztec royalty, Montezuma was a man destined for greatness. As ruler, he expanded his empire’s reach until it dominated modern Mexico. Yet, when the aliens arrived, this great man could do nothing but watch as his entire world crumbled. In today’s video, we’re journeying through an unrivaled Mesoamerican superpower… and uncovering the tragic life of its last true emperor.

Childhood Lost

In the great library of history, there are leaders whose lives fill not just shelves, but entire rooms. People like George Washington, whose every single deed has been pored over innumerable times. On the other end of the scale, you have leaders whose lives are only a single, slim volume. Rulers whose existence is such a mystery that we know almost nothing about them.

It’s into this latter category that Montezuma’s life falls.

Born circa 1467 AD, Montezuma II is one of those historical figures haunted by misconceptions. For instance, while this video is titled “Montezuma II”, Aztec culture didn’t have regnal numbers. To them, he’d have just been plain old Montezuma.

Only even that isn’t quite right. Properly rendered, his name should be Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, which can be delightfully translated as “angry like a lord”.

An emotion I’m sure we’ve all experienced at one point or another.

We mention this not to be pedantic dicks, but to demonstrate just how little most of us know one of America’s most significant pre-Columbian figures.

But even scholars don’t know a great deal more.

That’s because a whole ton of Montezuma’s past has been lost to history. We know, more or less, when he was born: in the last years of the reign of his namesake, the first Montezuma. We also have a good overview of his family tree. We know his father was the future ruler Axayacatl, and that his uncle was also an emperor in waiting called Ahuitzotl.

But if you’re here to discover what kind of relationship Montezuma had with his mother, or what he enjoyed doing as a kid, well, we hate to disappoint, but we can’t say any of that for certain.

What we can say, though, is that Montezuma came of age during a time of transformation.

He was just two or three years old when the Aztec emperor – or, more properly, the Tlatoani, meaning speaker – Montezuma I died. In the aftermath, a council of elders came together to decide who would be next to rule the empire.

Unlike European society, Aztec culture didn’t automatically award the throne to the dead guy’s eldest son, instead electing someone from a narrow list of candidates.

This would turn out to be very lucky for the young prince.

Despite his uncle Ahuitzotl being older, it was Montezuma’s father, Axayacatl, who was eventually chosen to become Tlatoani.

From that point on, Montezuma’s already-pampered life likely got only cushier.

As son of the Tlatoani – and the Aztecs considered their Tlatoani to be literally divine – Montezuma would’ve sat at the top of a gigantic pyramid made up of rigid social classes. He would’ve received the best education, learning the dark arts of warfare and politics amid settings so opulent they rivaled Versailles.

By the time he came of age, Montezuma would’ve been as ready to rule as any king or emperor in history.

So maybe it’s time we discussed exactly what he was gonna rule.

In the Dark Forest

The Aztec Empire was one of America’s greatest civilizations. At its height, it ruled millions of people – we’ve seen estimates ranging from six million to over eleven million – and around five hundred cities. Most of what we’d now call Central Mexico fell within its lands, and its southern extremity stretched to the fringes of Guatemala.

But this wasn’t some ancient civilization, like the Mayan Empire, that had taken over a thousand years to build. At the time Montezuma’s father Axayacatl assumed the throne in 1469, the Aztec Empire had been standing less than 50 years.

The people we today call the Aztecs first arrived in the Valley of Mexico in the 13th Century.

Back then, the fertile valley was basically mesoamerica’s cradle of civilization. Great empires like the Toltecs had risen and fallen here.

But, by the time the early Aztecs arrived, the days of a central power controlling the region were over. Instead, the valley was a place of innumerable city states, all fighting in a Darwinian struggle for survival.

Those who were good at war flourished. Those who weren’t went the way of the dodo.

Luckily for the Aztecs, war was something they excelled at.

Around the year 1325 AD – at least, according to tradition – the migrant Aztecs established a city on an island in the middle of the valley.

Known as Tenochtitlan, it became their center of power.

But this wasn’t yet power on a grand scale. In the dark forest of Mesoamerican society, you couldn’t get too powerful without attracting the attention of a bigger rival. It wasn’t long before Tenochtitlan found itself under the thumb of the mighty Tepanec Empire.

But in this cutthroat era, the balance of power shifted all too easily.

In 1428, civil war erupted among the Tepanecs.

The ins and outs are complicated, but the upshot is that Tenochtitlan allied with two other city states – Texcoco, and Tlacopan – to destroy the Tepanec capital. When the fog of war finally cleared, the Tepanec empire was no more. Tenochtitlan’s Triple Alliance had won.

It was from this alliance that the Aztec Empire proper would be born.

Considering it only appeared in 1428, the empire expanded at a phenomenal rate.

Aztec Empire – ru.svg: Kaidor derivative work: Rowanwindwhistler (talk) – Aztec Empire – ru.svg, CC BY-SA 4.0

If you look at a map of Aztec conquests, you’ll see them go from a small smudge of territory around modern Mexico City, to a regional superpower in the blink of an eye.

By the time Montezuma was born, in 1467, the empire stretched from the Atlantic coast to within spitting distance of the Pacific.

Yet it would be wrong to think this was an empire in the regular sense. Whereas other historical empires, like the Romans, integrated new conquests into a relatively centralized state, the Aztecs were nowhere near as disciplined. Conquest by the Aztecs didn’t mean becoming an Aztec citizen so much as it meant a bunch of Nahuatl speakers defeating you, dumping a gigantic carving of their God on your temple, then demanding tribute.

In other words, the Aztec “empire” was more a bunch of loosely aligned city states with their own distinct identities, united mostly in their annoyance at paying all this tribute to Tenochtitlan.

The empire, then, was vast, but it was unstable. So long as it could remain the most-powerful beast in the dark forest, it would survive. But the moment a bigger, stronger predator came along…

Well, we’ll find out shortly.

First, we need to witness Montezuma’s rise to absolute power.

A Family Business

After Montezuma’s dad Axayacatl took the throne in 1469, it must’ve looked like the family was set.

But then Axayacatl managed to screw things completely up in a single decade.

In 1479, just after Montezuma turned ten, Axayacatl tried to conquer the Purépecha or Tarascan Empire… only for the Purépecha to hand the Aztecs be-feathered asses to them on an obsidian platter. The entire army was wiped out. Given the importance the Aztecs placed on their elites doing battle, it’s probably lucky Montezuma wasn’t yet old enough to fight, else this video would be ending right about now.

But Montezuma was still too young to be a warrior. So he avoided the fate of all those captured by the Tarascans, just as he avoided the fate his father suffered.

In 1480, Axayacatl fell ill. Within a year, he was dead, killed by a mysterious “wasting disease” that today looks more like a really unsubtle assassination via poison.

Exactly how the teenage Montezuma would’ve taken his dad’s death is an open question.

We know that, as Tlatoani, Axayacatl would’ve been given a send-off party befitting a God, his body burned atop a gigantic pyre in the middle of the city. But what Montezuma would’ve felt upon getting the news… upon seeing his father’s mortal remains turn into smoke and fan upwards into the night sky… we simply can’t say.

Was he sad? Proud? Did he swear then and there to one day do better than his useless old man?

Who knows?

After Axayacatl’s death, the empire went through a brief lull in which it was ruled by the magnificently useless Tizoc, before he, too, died of one of those “mysterious diseases” in 1486. In the wake of yet another Tlatoani getting bumped off with poison, the council of elders finally decided to place someone competent on the throne.

That man was Montezuma’s uncle, Ahuitzotl. And he ushered in the Aztec Golden Age.

Now, the Aztecs being the Aztecs, what was a golden age for them was more an age of “arrgh! No, please stop conquering me!” for everyone else. One of the first things Ahuitzotl did was celebrate his new reign by sacrificing between twenty thousand and eighty thousand prisoners atop the Templo Mayor.

This gory deed done, he set about vastly expanding his brand new empire.

Guess who was by his side the entire time.

By now Montezuma had grown into a powerful young man. He’d been trained in the art of Aztec warfare, in diplomacy. He’d even served as a high priest. Now he just had to prove himself in battle, prove himself worthy of his place in the royal family.

Luckily for Montezuma, he hadn’t inherited his father’s incompetence in warfare. First at Ahuitzotl’s side, then as his own man, he was going to conquer more land than any other Aztec in history.

Death or Glory

It’s hard to overstate just how important war was to the Aztecs.

Like, their foundation myth literally involved the God Huitzilopochtli leaping out the womb fully-armed and immediately decapitating his sister. For Aztec males, life was effectively like being in Street Fighter 2: a series of battles, in which you had to best an endless string of opponents to advance.

And this advancement was real. The clothes you could wear, the respect afforded to you, was all tied up in the number of people you’d defeated.

As a result, the Aztec nobility were on the frontlines of war, not hanging back avoiding the slaughter.

Not that any slaughter happened on the battlefield.

When Montezuma joined Ahuitzotl in his campaigns of conquest, he wouldn’t have been trying to kill his enemies. He’d have been fighting to disable them, to capture them.

Why? Because Aztec warfare sprang largely from one need.

The need to sacrifice humans.

Depending on where you get your history from, you might have either heard that the Aztecs were monsters who sacrificed innocents every day; or alternately that all accounts of Aztec human sacrifice were fabricated by the Spanish to justify conquering them.

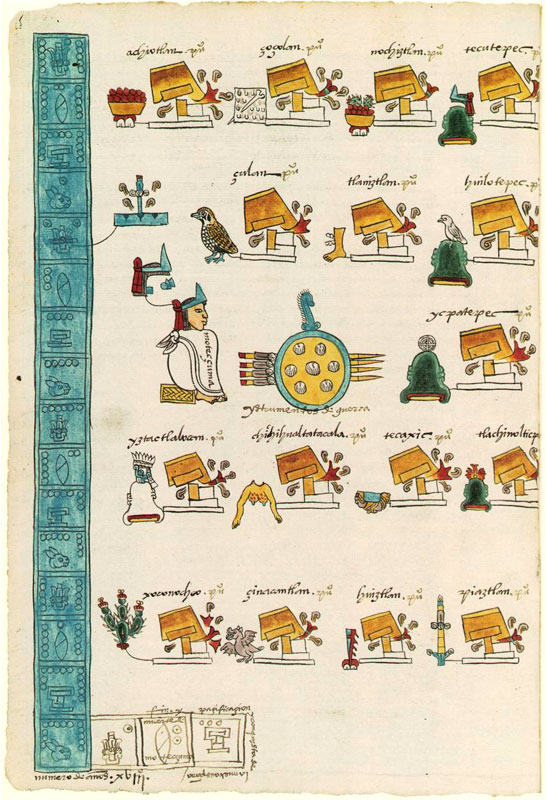

Credit: Arjuno3 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

Neither of these is exactly true. On the one hand, it’d be nonsense to say the Aztecs literally sacrificed someone every single day.

On the other, sacrifice was still something they did a ton of.

The Aztec calendar was broken up into 18 “months”, each of which had a major festival, all of them involving human sacrifice. We know this, because excavations in 2015 and 2018 dug up HUGE evidence, including towers of human skulls long thought to have been conquistador propaganda.

The Aztecs believed the Gods had given their own blood to create humanity. This blood debt needed to be paid back regularly, or the world would end.

It was to repay this debt that Aztec warfare took place, that young men like Montezuma went out to take prisoners in battle.

And Montezuma and uncle Ahuitzotl were absolute experts at winning battles.

As Ahuitzotl’s reign wore on, the two of them managed to finally connect the empire to the Pacific coast. To overrun the Oaxaca Valley. Together, they captured Xoconochco, right down on the Pacific Coast by the modern Guatemalan border.

Although Ahuitzotl was the mastermind, Montezuma was his trusted lieutenant, always right in the thick of the fighting.

By the time the boy turned 30, he was renowned as a ferocious warrior, a prime candidate to become Tlatoani.

Luckily, the chance soon presented itself.

Exactly how Ahuitzotl died is a mystery.

Some sources say he contracted another of those “wasting diseases”; while others say he died from a blow to the head while escaping a flood.

Either way, the outcome was the same.

In 1502, Ahuitzotl the conqueror was burned atop a massive funeral pyre in the heart of Tenochtitlan. Shortly after, the council of elders gathered to elect the new Aztec leader.

You won’t be surprised to hear that Montezuma was the winner.

King of the World

One of the coolest Aztec relics is the coronation stone of Montezuma.

Carved as part of the lavish ceremonies surrounding his ascension to Tlatoani, it gives us a date of “year 11 reed,” day “1 crocodile”, AKA 15 July, 1503. It’s one of the few specific dates we have regarding Montezuma’s life. And it’s a fair bet to say it was the greatest day of all.

As Tlatoani, Montezuma was given a palace to live in that would make even the sultan of Brunei vomit with envy.

There were hanging gardens. Pools of fresh and salt water to bathe in. A private zoo filled with jaguars and eagles. Ten whole rooms dedicated to a vast aviary. 3,000 attendants fulfilled Montezuma’s every desire. For just a single meal, chefs would prepare hundreds of dishes that the emperor could pick from at his leisure.

He wore sandals made of gold. Had jugglers, acrobats, albinos, and dwarves at his beck and call.

Yet Montezuma’s reign wasn’t just about indulgence.

There was also conquest. The year he was crowned, 1503, Montezuma launched a “coronation war” against the city of Nopallan. But this was just the warm-up act. Over the next 16 years, Montezuma initiated four major wars, eventually growing the empire so large it effectively swallowed central Mexico.

By the end, the only viable enemies the Aztecs had left were the pesky Tarascans who had handed Axayacatl’s ass to him back in 1479, and the Tlaxcala.

But even the Tlaxcala were hemmed in, a small enclave of hostile territory, completely surrounded by the Aztec superpower.

Montezuma hadn’t just fought alongside Ahuitzotl. He’d learned the arts of conquest from him.

Yet Montezuma was even more ambitious than his uncle had been.

As Tlatoani, Montezuma reduced the power of his Tlacaellel – a guy we might call the chief of internal affairs.

In effect, he swiped a load of powers, elevating himself from “living God” to “living God who’s also a dictator”.

It’s kinda tempting to see Montezuma on the eve of the Spanish invasion as a leader in his prime; a guy so powerful at the top of an empire so great that its collapse at the hands of the Europeans is the ultimate black swan event.

But that’s not exactly true.

Even before 1519, there were signs that Montezuma’s empire was in trouble. In 1515, for example, Montezuma tried to finally tame the Tlaxcala enclave, only to suffer a defeat almost as humiliating as the one that toppled his dad.

In the wake of this gigantic screw-up, insurrections broke out in the empire’s outer provinces. City states started looking sidelong at one another, quietly wondering if now might be the time to break free of Tenochtitlan.

We don’t want to speculate too much, but it’s possible the empire was already close to disintegration.

Yet, we’ll never know if it would’ve fallen apart under Montezuma’s rule.

In 1515, reports reached Tenochtitlan of “floating temples” spotted off the coast.

Two years later, the first of these temples landed on the shores of the Aztec Empire, its grand white sails billowing in the winds. The Aztecs didn’t know it, but the aliens had just arrived; travelers from another world – the Old World.

When they finally decided to explore Mexico, it would be the end of everything Montezuma had ever known.

The Invasion

Almost every account you’ll ever hear of Hernan Cortez’s invasion tells it from the point of view of the Europeans; following them as they battle their way into the interior, as they defeat city after city.

Certainly, it makes for a juicy narrative. There’s lots of adventure, plenty of action. But even more compelling might be the narrative from inside Tenochtitlan. How it must’ve felt as reports of floating temples and strange white men gave way to stories of butchery and violence.

How it must’ve felt as those stories got closer and closer to the capital, as the aliens drew nearer. Frustratingly, this is another of those times when we basically have to guess, so sparse are the records from the Aztec side.

But we do have some clues.

Infrogmation – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

We can assume Montezuma was nervous about the invaders the moment they landed, since he sent them gifts of gold and silver – the traditional way of resolving disputes in Aztec society.

Unfortunately, the Europeans saw these gifts not as a message saying “thanks for coming, you can go now”, but an invitation to do some serious looting. This brings us to our second assumption: that Montezuma received news of the aliens with mounting despair.

Cortez and his men subdued the coastal tribes with ease. They then fought Montezuma’s old enemies, the Tlaxcala and, once they’d won, asked the Tlaxcala to join forces with them.

By summer, reports would’ve been flooding into Tenochtitlan of the massacre at Cholula, where the Spaniards put 6,000 loyal Aztec subjects to the sword. You can almost imagine the fear gripping Montezuma’s heart.

For the best part of a century, the Aztecs had been the top predator in the dark forest of Mesoamerica.

And now here came the superpredator society, one that could brush Aztec warriors aside as easily as Montezuma could swat a fly.

The only questioned was how could he stop them destroying Tenochtitlan?

In November, 1519, the aliens were at last spotted approaching the Aztec capital. Much has been made of the fact that Montezuma put up no resistance, including the now-disproved tale that the Aztec Tlatoani mistook Cortez for a God.

But there seems to be an obvious answer. Montezuma knew resistance was futile.

Better to extend the hand of friendship and hope for the best than to fight a battle you’re destined to lose.

On November 8, Cortez was welcomed inside the great city for the first time. While it was a strange experience for the Spaniard, it must’ve been even stranger for Montezuma. Here he was, showing this unknowable warrior around his capital, pointing out its sacred temples, grand canals, and flower gardens, all while never knowing if they would still be standing in a few days’ time.

Montezuma could never have guessed, as he led his guest into the heart of the temple precinct, that this was the greatest city Cortez had ever seen. That it overshadowed anything in contemporary Europe.

That Cortez had already decided to present it intact to his own emperor.

A few days after the Spanish arrived, Montezuma’s slow downfall began. Cortez took him hostage, forcing him to swear allegiance to Charles V, and placing him under house arrest.

From now on, Cortez would rule the city from behind the scenes. Montezuma would just be a figurehead, a puppet for the Spanish. Perhaps the last true Aztec emperor agreed in the hopes that Cortez would spare his people. Perhaps he was simply afraid for his own life, and willing to do anything to stay alive.

Either way, Montezuma did exactly as Cortez wished.

From that moment on, Aztec society was already dead.

The End of Days

It’s hard to think of many puppet rulers who’ve had it good, but perhaps few have had it quite so bad as Montezuma. Although he still lived in luxury, was still officially a deity, in reality he was nothing but a Spanish slave, forced to justify the most outrageous acts to an increasingly angry public.

It was Montezuma, for example, who had to go out and calm his people when the Spaniards placed a giant cross atop the great temple.

But if Montezuma thought life as Cortez’s lapdog was bad, it was about to get even worse.

In early 1520, Cortez was called away from Tenochtitlan.

Probably all Montezuma was told was that the Spaniard was going, and would leave Pedro de Alvarado in charge.

Bad move.

Where Cortez was like a crafty fox, worming his way into control of Tenochtitlan, Alvarado was like a particularly obtuse bull that’s been blindfolded and dropped into a porcelain factory.

As the power behind the curtain, Alvarado began having elite Aztecs executed on a whim. Each time, he made Montezuma go out and do his thing, telling the enraged crowds that everything was still cool, you guys.

As a smallpox epidemic broke out in the empire, carried in by the conquistadors, Tenochtitlan reached boiling point.

It was at this time that Alvarado did something even Montezuma couldn’t justify. In May, 1520, one of the Aztec’s great, frequent rituals took place in the temple precinct. As warriors dressed in feathers danced and whirled under the dark sky, drummers beat out a rhythm; rising to a crescendo, preparing the city for another sacrifice.

But the sacrifice never came.

Instead, the Spaniards strode into the precinct, unsheathed their swords…

…and, one by one, the great Aztec warriors were struck down, their bodies dismembered on sacred ground.

It was the end of Montezuma’s puppet regime. Tenochtitlan exploded. The Spaniards were besieged, the city of 200,000 souls suddenly an inferno. At some point in June, Cortez managed to slip back in and demand Montezuma go out to calm the crowd.

There are two versions of what happened next.

The first is that, docile to the end, Montezuma went out on a balcony to speak to his people. There, the rioting crowd threw rocks at their false God, until one struck him on the head, killing him instantly. The second is more prosaic. It claims that Cortez realized Montezuma’s usefulness was over and had him summarily executed.

Montezuma II died on either 29 or 30 June, 1520.

The very next night, the Spanish tried to flee Tenochtitlan, only for dozens of them to meet their fates, either at the hands of the Aztecs, or drowning while trying to cross the lake. Known in Spain as the Night of Tears, the botched flight from Tenochtitlan marked the point the Spanish conquest came its closest to collapse.

But it didn’t quite end there.

Just 9 months later, Cortez would be back, at the head of an invasion force marching on the Aztec capital. But that’s another story. For now, for this video, we end with Montezuma, lying dead on a balcony in a pool of his own blood, or perhaps bleeding out on the tip of a Spanish sword.

At the end of all that carnage, then, we can finally ask: who really was Montezuma II?

Well, he was unlucky, for one. Had he died of one of those mysterious “wasting diseases” before Cortez showed up, it’s likely he’d be remembered as the greatest Aztec emperor.

But there was more to Montezuma’s life than simply being the guy in charge when the aliens arrived.

Although much of it is mysterious, Montezuma’s story remains a window into an entire other world. Into a culture so different from ours that we can never hope to fully understand it.

Yet in the tale of his struggles, in his life and death, we can still catch enough glimpses of the Aztec world to wonder what it must’ve been like. How it must’ve felt to be living in this time and place when the apocalypse finally arrived.

The Spanish may have wiped out Montezuma’s empire, they may have ground his people into dust. But his name still lives on, a reminder of an entire forgotten world.

Source:

Unbelievably epic, 4 hr podcast on the entire history of the Aztecs: https://podcasts.google.com/?feed=aHR0cDovL2ZlZWRzLnNvdW5kY2xvdWQuY29tL3VzZXJzL3NvdW5kY2xvdWQ6dXNlcnM6NTcyMTE5NDEwL3NvdW5kcy5yc3M&episode=dGFnOnNvdW5kY2xvdWQsMjAxMDp0cmFja3MvNzI4NTYwMzk5&hl=en-CZ&ved=2ahUKEwjZ26nJ8YDpAhWOy6QKHYv9AwcQieUEegQIChAG&ep=6

BBC In Our Time on the Aztecs: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00548v0

BBC In Our Times on the siege of Tenochtitlan: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b016924x

Good overview of the conquest from the Spanish side: https://www.historyextra.com/period/tudor/hernan-cortes-montezuma-tenochtitlan-aztec-conquest-conquistadors/

Nat Geo’s version of the same: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/magazine/2016/05-06/cortes-tenochtitlan/

Very detailed bio of Montezuma: https://www.ancient.eu/Montezuma/

History’s take: https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/spanish-retreat-from-aztec-capital

Montezuma before the Spanish: https://www.thoughtco.com/emperor-montezuma-before-the-spanish-2136261

Aztec human sacrifice: https://www.history.com/news/aztec-human-sacrifice-religion

Montezuma’s coronation stone: https://www.artic.edu/artworks/75644/coronation-stone-of-motecuhzoma-ii-stone-of-the-five-suns

Overview of the Aztec Empire: https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-americas/aztecs

Aztec history in detail: https://www.ancient.eu/Aztec_Civilization/

What was life like for a regular Aztec person? https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/life-in-the-provinces-of-the-aztec-2005-01/

Map of the Aztec Empire pre-conquest: https://cs.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soubor:Territorial_Organization_of_the_Aztec_Empire_1519.png

How the empire grew over time: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aztec_Empire_-_es.svg

Other source on the Aztec campaigns in Tehuantepec and Xoconochco: https://books.google.cz/books?id=fh29E1nLlBgC&pg=PA147&lpg=PA147&dq=Aztec+campaigns+in+Tehuantepec+and+Xoconochco&source=bl&ots=L9dPzU9mUp&sig=ACfU3U0vF8mbrmmb-GyCZdiJG_F7Q8FI6A&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiV5fOhi4HpAhVG2aQKHVh8AfQQ6AEwF3oECA4QAQ#v=onepage&q=Aztec%20campaigns%20in%20Tehuantepec%20and%20Xoconochco&f=false

Ahuitzotl: https://www.ancient.eu/Ahuitzotl/