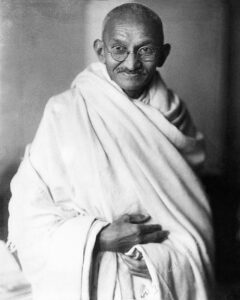

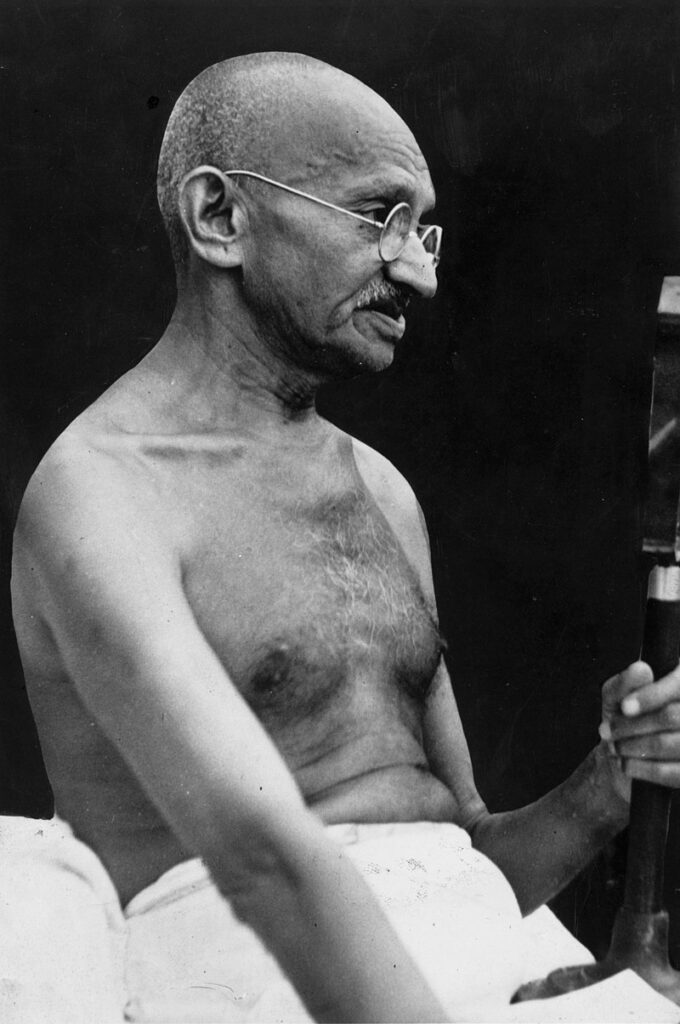

Mohandas Gandhi started out as a scared, painfully shy young man. Yet he was transformed by injustice to step beyond his insecurities to become the 20th Century’s most influential champion of social justice and the standard bearer for non-violent resistance. His example of humility, courage and quiet dignity has inspired millions and been the catalyst for the change to a better world. In this week’s Biographic’s, we discover the inspirational story the Great Soul, Mahatma Gandhi.

Formative Years

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on October 2nd, 1869 in the coastal Indian town of Porbandar. He was the youngest of six children, which included two half-sisters from his father’s previous marriage. Mohandas’ father, Karamchand, was the diwan, or political leader, of Porbandar. His mother, Putlibai, was deeply religious, impressing strong Hindu beliefs on her children. Karamchand provided well for his family, who lived in a three-story house and had servants.

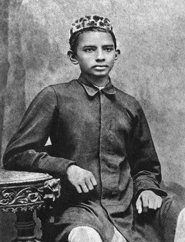

Mohandas was known by all as ‘Mohan’. He was especially devoted to his mother, who he considered to be a saint. Her piety made a deep impression upon him. When the boy wa

s five, his father was appointed the chief minister of the smaller inland city of Rajkot. After two years, the family joined him there. Mohan was a painfully shy child who kept to himself at school. When his lessons were done, he would run home in order to avoid having to talk to any of his peers. He was also a fearful child, who was terrified of many things, but especially the dark. He found his only solace in books, which were his constant companion.

When he was just seven years of age, as was the Hindu custom, Mohan became engaged to Kasturba Makhanji Kapadia, who was a few months older than him. The arranged marriage was completed when Mohan turned 13. The planning for the lavish wedding ceremony and adjustment to married life meant that he had to take a year off from his schooling.

He was an average student at best, though he tried hard to please his teachers. He had no interest in sports, games or social activities with his peers. He did, however, make one friend around this time. He was a Muslim boy by the name of Sheikh Mehtab. Sheikh was older and more street smart than Mohan. He was also physically larger and stronger. He chided Mohan about his frail condition and told him that if he ate meat, he would get much bigger and stronger. This was strictly against Hindu beliefs but Mohan met his friend in secret one day and had his first taste of meat. Even though it caused him to vomit, he continued to eat it for the next year without letting anyone else know. Over that period, Sheikh also took him to a brothel, an experience which was an embarrassing disaster for the impressionable teen. Realizing that Sheikh was a bad influence he cut off association with him and returned to a strict vegetarian diet.

Mohan’s father, Karamchand, died when the boy was 16. The grief was compounded when Mohan and Kasturba’s first child died at less than a week old. The couple would go on to have four more children, with the first being born in 1888. Mohan completed college at the age of 18 and enrolled at Samaldas College in Bhavnagar State. However, he disliked the lecture style of teaching and dropped out after a few months. He had set his sights on becoming a lawyer and eventually becoming a diwan like his father. A family friend suggested that he should go to England to study, where it was easier to pass the bar. It was agreed that this would be the best course for Mohan. The shy, retiring Hindu boy was headed for the bright lights of London.

London

On August 10th, 1888 Mohan left his family, including wife Kasturba and one-month old son, Harilal and headed for Bombay, where he boarded a ship bound for London. Before leaving Bombay, however, he had been summoned by the leader of his caste, the Modh Bania, and warned him that if he went to England he would be tempted to break the rules of Hinduism. He was told to either abandon his plans or be excommunicated from the caste. Gandhi accepted this consequence and continued on his way.

Fitting into Western culture was a shock for the eighteen-year-old. Everything was so different to what he had known back in India. Still he did his best to fit in, buying a fine suite, complete with leather gloves, top hat and silver tipped cane. He also paid for lessons in elocution, manners and dance. His biggest challenge was with regard to his diet. He had vowed to his mother that he would not eat meat, but it was very difficult to find restaurants that catered to vegetarians. His chronic shyness prevented him from requesting alternatives to what was offered. Finally, he found a vegetarian restaurant along with a whole community of vegetarians. He joined the London Vegetarian Society.

Despite his difficulties with fitting into London life, Gandhi did well academically. He passed his law exams in June 1891. His friends at the Vegetarian Society held a celebratory evening in his honor. When it came time to give a speech, however, Mohan was so nervous that he simply rose and said ‘Thank you’.

South Africa

On his return to India, Mohan was met at Bombay harbor by his older brother who bore terrible news. Their mother, Putlibai, had died in his absence. Mohan’s grief was compounded with the consequences of his overseas foray: he was now disfellowshipped from his caste. In order to please his family members, he agreed to bathe in a sacred river in order to wash away the sins of England. This precipitated his re-entry into the caste.

Gandhi looked for work as a lawyer in Bombay. However, his chronic shyness was still preventing him from making any advancement. He recalled how he felt presenting his first case before the court . . .

My head was reeling and it felt as if the whole court was doing likewise.

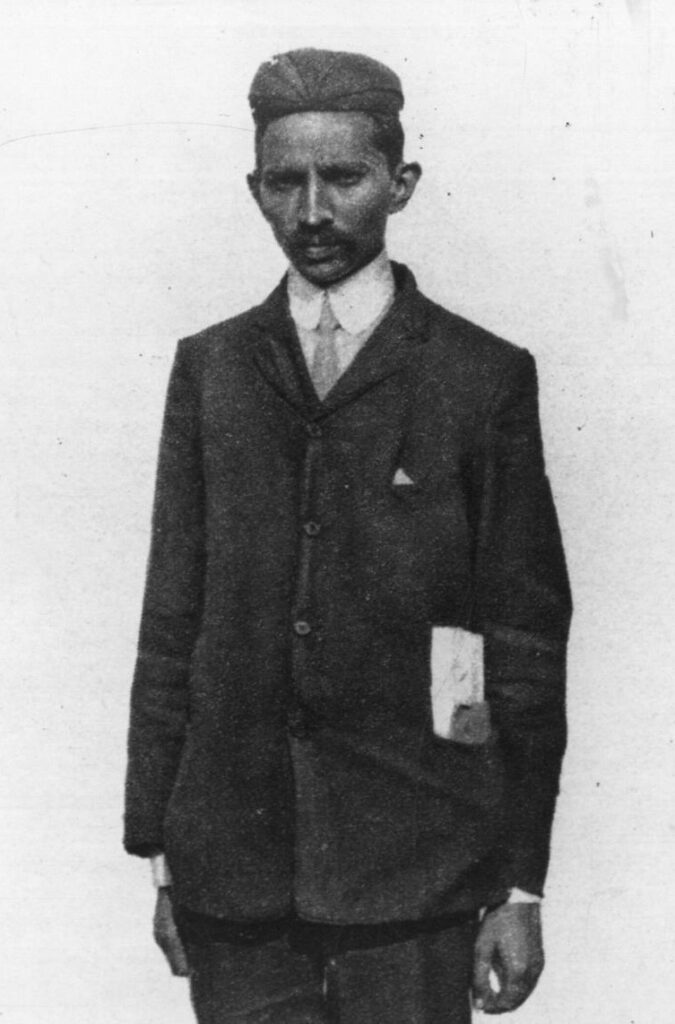

He retreated to the less imposing town of Rajkot and established a small law office there. Shortly thereafter he received an offer from a merchant who had been a friend of his father. This man was now based in South Africa and he needed a lawyer to help with a court case. The yearlong job was offered to Gandhi and he accepted it, despite recently becoming a father again. He kept his wife and two young sons under the care of his brother and headed off for Durban, South Africa in April, 1893.

After settling in to his new surroundings, Gandhi took the train to Pretoria where the court case was to be tried. He purchased a first-class ticket. However, on one of the stops a European man boarded the car that he was in. The man resented seeing an Indian in first class and left to find the train conductor. The two men returned and Gandhi was ordered to go to the third-class section. Gandhi showed them his first class ticket and refused to move. At that, train security was called and Gandhi was kicked off the train. He had to go the rest of the way in a horse drawn carriage. However, the white passengers refused to let an Indian sit inside with them and he was made to sit on the outside footboard. He later recalled . . .

The insult was more than I could bear.

This was the watershed experience of Mohandas Gandhi’s life. As if by miracle, he shook off his timid nature and stepped forward as a leader of the oppressed. When he arrived in Pretoria, he called a meeting of the Indian community and gave the first speech of his life, calling for the Indians to stand up for their rights.

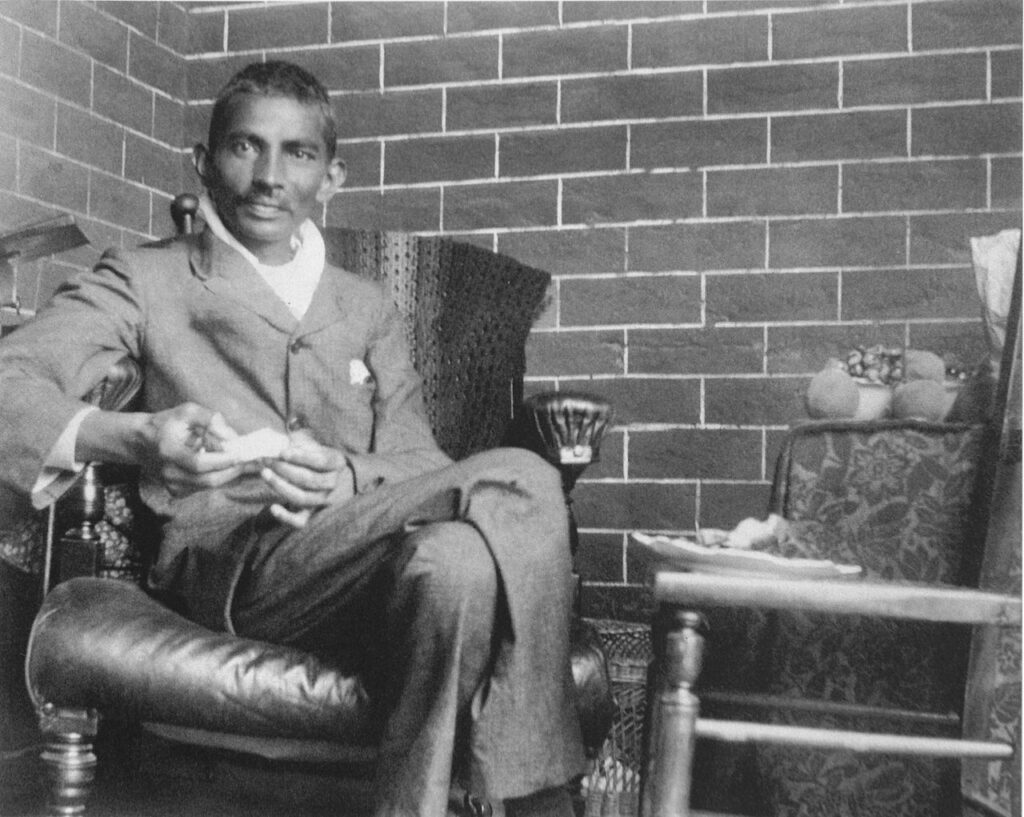

Once his work on the court case was complete, Gandhi decided to stay and continue the fight for Indian rights. In 1894 he established the Natal Indian Congress to give Indians a political voice. He established himself as a leader in the local community, giving free legal advice and offering support.

In 1896, after three years in South Africa, Gandhi returned to India to collect his family. He returned with his with and two sons, now aged nine and five, along with a nephew. Gandhi demanded that his family dress as Europeans and eat with knives and forks, as was the way with Indians in South Africa. This caused tension within the family. Still, two more sons were added to the family in the coming years.

When the Boer War broke out in 1899, Gandhi felt that if the Indians supported the Government, they would be rewarded with better treatment. He organized an Indian Ambulance Corps who were a valuable asset to the army. But the loyalty went unrewarded with the harsh treatment continuing. During this time, Gandhi developed the life philosophy which was to guide him for the remainder of his days. He called it Satyagraha, which means ‘devotion to the truth’. The three core tenets of the belief were non-cooperation, noon-violence and non-possession.

In 1906, the South African province of Transvaal enacted a law that required all Indians to register and be given identity cards. The police were allowed to stop and demand their registration at any time. No other group had this requirement. Gandhi advocated the use of Satyagraha to counter the law. He told the people not to register. As a result, he and many others were thrown in jail. But Gandhi taught that righteous imprisonment was an honorable thing. The concept of Satyagraha took hold and Gandhi established a number of Satyagraha settlements. The people in these settlements practiced non-possession, living a simple, austere life. Gandhi also organized a large coal miners strike. The men practiced non-cooperation by refusing to work and non-violence by refusing to react when they were attacked by the authorities.

In July, 1914, the South African Government passed the Indian Relief Act, which went some way to righting the wrongs that had been heaped upon the Indian community. The twenty years of struggle that Gandhi had put into the cause were largely responsible these changes. He was now ready to return to India, bringing his Satyagraha philosophy with him.

Mahatma

Gandhi was surprised to receive a hero’s welcome back to India. His efforts on behalf of South African Indians had been well reported over the years. An Indian poet referred to him as Mahatma, meaning ‘Great Soul’ and the name took hold as assign of respect. The shy, indecisive young man who had left in 1893 returned in 1915 as a leader. And he was a leader with a mission – Indian self-rule.

Gandhi also challenged his own people to look at the unfair treatment within their own culture. He challenged the caste system and, especially the terrible treatment of the lowest class, known as Untouchables. He established a Satyagraha settlement in which the people spun yarn and farmed fruit trees. Gandhi accepted Untouchables into the community and taught the local peasants proper hygiene and encouraged factory workers to wage peaceful strikes against their unfair working conditions.

Despite his belief in non-violence, Gandhi supported the British war effort during World War One. At war’s end, the government passed an act making it illegal for any group to organize in opposition to the government. Gandhi called for a mass strike to protest the law and for one day, the whole of India came to a standstill. It was a clear evidence of the power that Gandhi was able to wield. Yet, when reports filtered in that some Indians had resorted to violence on the day of peaceful protest, he was bitterly disappointed. He knew that his people, as a whole, were not yet ready for Satyagraha.

The British were concerned that there would be further outbreaks of violence and so a law was passed banning any gatherings of Indians in the city of Amritsar, one of the places where violence had occurred. The following day was the beginning of the religious New Year and about 10,000 people gathered in the town square. They had not yet heard the news of the ban. As they were peacefully listening to a speech, ninety soldiers and two armored cars turned up. They blocked off the only exit and proceeded to fire their weapons into the unarmed crowd of men, women and children. 379 people were killed that day, with more than a thousand being wounded.

Non-Violent Resistance

In 1920, Gandhi became the leader of the Indian National Congress, dvocating his non-violent resistance and instituting strikes and boycotts to bring pressure on the system. Gandhi told the people to boycott British cloth and spin their own. He vowed to spend time spinning every day and took to wearing clothing made of handspun cloth. He made the spinning wheel a national symbol for Indian independence.

Gandhi travelled throughout the massive countryside, going mostly on foot. He lived with the downtrodden in their makeshift dwellings and listened to their problems. To them he was a saintly figure and they referred to him as Bapu, meaning ‘father’.

In March, 1922, Gandhi was arrested for sedition. The trial gave him a platform to expound upon the unfair treatment of Indians and his refusal to cooperate with unjust laws. Pleading guilty he was sentenced to six years imprisonment. Gandhi was not deterred, using his time of confinement to read and study. After two years he was released. His focus now was on creating harmony between Hindus and Muslims. For centuries the two groups had been at loggerheads with one another, with violent clashes often breaking out. Gandhi saw that independence was impossible without unity and he was determined to bring the two groups together.

Gandhi undertook a hunger fast as a tool to bring the Hindus and Muslims together. For three weeks he only drank water. As their Bapeu grew weaker by the day, the Hindus and Muslims finally agreed to put aside their differences in order to stop his suffering.

The Salt March

On March 12, 1930 Gandhi begin a month-long trek from his ashram in Andrabhad to the sea. Hundreds and then thousands of followers of all religions and castes joined him along the way. News of the march filled papers around the world.

The British had long imposed a law making it illegal for anyone to make salt from seawater in India. As a result, they were able to make huge profits from their salt tax. Twenty fours days after setting out on his march to the sea, Gandhi arrived at Dandi on the gulf coast of Cambay. The following morning Gandhi walked out into the sea water to bathe. On his return he picked up a handful of salt in defiance of the salt act. This act was the signal for his countrymen and up and down India’s coastline thousands of others began collecting seawater in order to make and sell salt.

In major cities people gathered, only to be beaten by the police. Many were arrested, including Gandhi who was thrown in prison for a second time. Yet the British could not silence the Mahatma. Officials now realized that this man held a powerful sway over the masses. He could not be ignored. Furthermore, the British government, both in India and at home, were being pressured by other governments to release Gandhi from jail. Finally, the British viceroy in India, Lord Irwin, met with Gandhi. After lengthy discussion they came to a truce – Gandhi would call off the demonstrations, the prisoners would all be released and Indians would be allowed to make their own salt.

In 1931, Gandhi travelled to London to represent the Indian National Congress at an International Round Table Conference. He called for Indian Independence from Britain. Rather than mix with the other delegates in their five-star hotels, Gandhi stayed with an old friend and spent his days walking around the slums dressed in his traditional home spun khadi and sandals. He was, by now, a famous international figure and newsreels of his visit were shown in movie theaters around the world.

Fasting for Victory

Shortly after returning to India, Gandhi was again arrested for inciting civil disobedience. While he was in prison the British government passed a law that discriminated against the Untouchables in court proceedings. Gandhi was infuriated and announced that he would not eat until this law was revoked. Fearing that his death would create a martyrdom that would doom them in the eyes of the world, the authorities caved in and the law was rescinded.

When Britain declared war on Germany in 1939, Gandhi told the authorities that Indians would only join the war effort if they were promised their independence. Three years later, he started a ‘Quit India’ movement. As always, he planned for the campaign to be non-violent. But things soon got out of hand and riots broke out across the country. The authorities blamed Gandhi and once more he was thrown in jail. His beloved wife, Kasturba was also imprisoned. She soon became ill, dying in custody on February 22nd, 1944.

Following his wife’s death, Gandhi himself grew weak with malaria. The authorizes agreed to release him in May, 1944 and he went to Bombay to recover and recuperate.

The end of World War Two saw Great Britain on its knees. Though victorious it had spent exorbitant amounts in the effect and now no longer had the resources to maintain its rule in India. With little choice in the matter, Britain offered India its independence. It was the grand victory that Gandhi had been fighting for the past 30 years.

Even though the nation was now free to rule itself, India was still plagued with deep division between Hindus and Muslims. The only solution seemed to be to divide the country into Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan. This was a move that greatly displeasing to Gandhi who longed for unity between the two groups.

In the weeks following the creation of Pakistan there were violent clashes between Muslims and Hindus up and down the country. Massacres occurred throughout 1947 with both sides equally responsible for the bloodshed. Hundreds of thousands of people died and there were riots in most of the large cities.

On January 13th, 1948, the 78-year Gandhi began a fast in order to get the madness to stop. He was so despondent that he refused to even drink water. Despite the physical pain that he was in, he still led a prayer meeting from his bed. His words were broadcast round the entire country. Fine days into his fast Muslim and Hindu leaders agreed to a peace accord.

A Great Light Extinguished

However, Gandhi was still very concerned about the direction the fledgling nation was taking. New Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was constantly at odds with his deputy Vallabhbhai Patel and Gandhi counseled both men to make peace. On January 30th, 1948 had been in a meeting with Patel. Just after five p.m., he came out into the garden of the Birla House in Delhi to offer prayers. Weakened from his recent fast, he leaned on two of his followers for support as he walked. A crowd of some 500 people were waiting to greet him. As he made his way to the platform, a Hindu extremist, angered at Gandhi’s leniency toward the Muslims, stepped forward. He bowed before the Mahatma and then pulled out a pistol and fired three shots in succession at point blank range. Within half an hour the last breath of life had seeped out of his body and the Great Soul was no more.

When he heard the new of the Mahatma’s death, Prime Minister Nehru said . . .

The light has gone out of our lives and there is darkness everywhere.

Mohandas Gandhi was a light to not just the people of India but those of the entire world. His funeral procession through the streets of Delhi was attended by more than two million people. And years after his death, countless other millions, including a young Baptist Minister from Georgia named Martin Luther King, would find inspiration in his words and his legacy.

Sources:

Gandhi by Rowena Akinyemi

Gandhi: A Memoir by William L. Shirer

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ibagACLb-6s