In late 1814, the great powers of Europe gathered after the fall of Napoleon to discuss what to do next. At the time, the continent was in ruins. The old order had been exploded as effectively as if someone had detonated an atom bomb beneath it. Just as it would in 1945, Europe needed a new roadmap, a blueprint for the future. Designing that blueprint fell to one man: Metternich.

The foreign minister of the Austrian Empire, Metternich was a dandy, a womanizer, and a comically pompous fop. He was also one of the greatest diplomats who ever lived. Under his guidance, post-Napoleon Europe was forged into a conservative system that would last nearly 100 years. His blueprint ensured the continent’s 19th Century was far less bloody than either it’s 18th or 20th. Yet Metternich also tried to strangle the forces of nationalism at birth and, in doing so, set the stage for his own destruction. A master strategist to some, a vain buffoon to others, this is the life of Europe’s coachman.

Children of the Revolution

The world Metternich was born into would be unrecognizable to us today.

The center of Europe was dominated not by Germany, but by something known as the Holy Roman Empire, a millennia-old collection of tiny states all joined together.

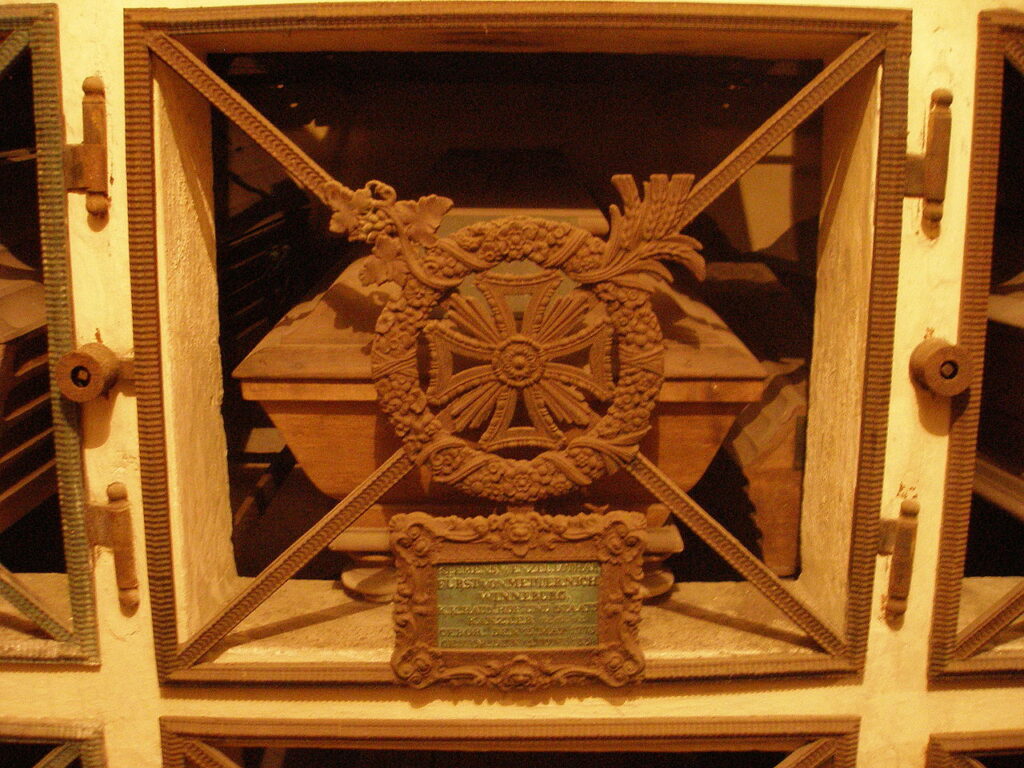

It was in one of these tiny states on the west bank of the Rhine that Metternich was born, on May 15, 1773. Or, to give him his full name: Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Fürst von Metternich-Winneburg-Beilstein.

Although Metternich was from the Germanic Holy Roman Empire, it was France that had the biggest impact on his early life.

Metternich’s home state was right on the buffer zone with the France of Louis XVI, so the boy grew up speaking better French than he did German, despite his father being an Austrian envoy.

This wasn’t all that unusual. France exerted a powerful pull over continental Europe in the 18th Century, and it seemed totally natural that Metternich should be sent off to the French city of Strasbourg to complete his education in 1788.

Unfortunately for the teenage Metternich, France at the end of the 1780s was a ticking timebomb.

On July 14, 1789, years of political turmoil in Paris exploded onto the streets. A mob stormed the Bastille armory, lynching the garrison commander.

It was the opening salvo of the French Revolution. And it was about to consume the entire continent.

Despite being the sort of age when waving the revolutionary flag might seem appealing, Metternich was disgusted by the unfolding drama.

For Metternich, any upending of the natural, conservative order of Europe was anathema. He decamped Strasbourg for Mainz post haste.

But Metternich was about to learn a very important lesson: when the cannonball of revolution gets rolling, there’s no escape.

In April, 1792, a French army whipped into a revolutionary frenzy invaded the Holy Roman Empire, burning, pillaging, destroying.

By now posted to a diplomatic position in the Austrian Netherlands (AKA Belgium) alongside his father, Metternich was forced to watch in horror as the French annexed his family’s home state in 1794, leaving them with nothing.

Barely had he got his head around this when the French overran the Austrian Netherlands and the boy and his father were forced to flee to Vienna.

Although the Metternichs were now refugees, they were still people of means, with good connections to Austria’s elite. So Metternich’s exile was less ‘Moses in the desert’ and more ‘rich playboy sleeping around Vienna’.

He even managed to marry Eleonore von Kaunitz, the daughter of Austria’s former chancellor. While Metternich was serially unfaithful to her, the marriage still meant his family going up in the world of Austrian politics.

But fate, and France, weren’t done with Metternich. On November 9, 1799, a French army officer staged a coup in Paris, putting himself in charge of the revolutionary war machine.

His name was Napoleon Bonaparte. And he was about to plunge Europe into chaos.

The Napoleonic Era

From Metternich’s perspective, the 19th Century must have felt like settling into a comfy armchair that suddenly grows teeth and devours you.

In 1801, Vienna’s newest man about town was promoted to ambassador and sent first to Dresden, and then to Berlin.

As Napoleon kept conquering, Metternich enjoyed the Prussian capital’s nightlife, all while gamely trying to persuade his hosts to join Vienna in war against France.

For a guy known for his diplomatic acumen, Metternich totally messed up this one. After years of cajoling, the Prussians finally put their foot down in 1805 and told the Austrian fop “Nein!”

This was the moment the geopolitical armchair swallowed the young ambassador whole.

On December 2, 1806, the Russian, Holy Roman, and Austrian armies – minus Prussia – all met to battle France at Austerlitz.

The Napoleonic army mopped the floor with them.

The Third Coalition lost the battle so badly the Holy Roman Empire was destroyed. Austria was forced to become allies with France.

Would things have gone different if Prussia had been there? It’s hard to say, but they couldn’t exactly have gone worse.

Still, Metternich’s catastrophic fail in Berlin didn’t stop him from getting an ambassadorship to Paris under Austria’s now pro-Napoleon leadership.

Sadly, Metternich hadn’t learned from his mistakes.

On May 2, 1808, an uprising in French-occupied Spain triggered a crisis in Paris. Egged on by Metternich’s breathless reports that Napoleon was losing his grip on power, Vienna took a risky gamble. In 1809, Austria rolled everything on a surprise attack.

Care to guess how this one went?

The War of the Fifth Coalition was a monumental embarrassment for Austria. Napoleon crushed them.

Not only that, he imposed one of the most humiliating peace treaties in history. Vienna lost a ton of territory, and was forced to pay Paris a ton of money.

For Metternich personally, though, things turned out surprisingly well. In the aftermath of the new treaty, he escaped blame. Not only that, he got promoted.

On October 8, 1809 Emperor Francis I made Metternich, then just 36 years old, foreign minister. He would hold the post for 40 years.

With Napoleon now basically in charge of Europe, Austria’s new foreign minister was forced to use all his legendary charm to try and placate Paris.

This created some humiliating moments, such as when Napoleon invaded Russia in 1812.

Austria was forced to send its own army along in support of the French. While Metternich managed to secure their nominal independence under Austrian commanders, it was crumbs from Napoleon’s table.

Or so it seemed.

When Napoleon’s latest adventure unexpectedly blew up in his face, Austria was able to sign a peace deal with the Russians. Vienna could then sit out the catastrophic French retreat across the continent.

For his part, Metternich didn’t believe this was really the end of Napoleon. In mid-1813, he tried to broker a peace between France and Russia and Prussia that would allow Napoleon to stay on the throne.

It was only when Napoleon said “non” that Metternich signed Austria up to the Sixth Coalition.

If you recognize the name “the Sixth Coalition”, it’s because these are the guys that actually did it, the ones that rid Europe of its tyrant.

On March 31, 1814, the armies of the Sixth Coalition captured Paris. With Cossacks marching down the banks of the Seine, Napoleon finally threw in the towel.

The Petit Corporal abdicated and was exiled to the island of Elba. Across Europe, cries of victory went up.

There was just one teeny, tiny problem.

What the heck did everyone do now?

The Congress of Vienna #1: Creating the Congress

It’s time for us to take a quick step back in time to something called the Treaty of Utrecht.

Signed in 1713 at the end of the War of Spanish Succession, the treaty was designed to keep Europe’s superpowers from superkilling each other by delicately balancing power between them.

The French Revolution had exposed the limits of this century old treaty. Even before Napoleon’s defeat in 1814, everyone knew a new treaty was needed, one that would insure against another continent-wide war.

Unfortunately, all the great powers that had just defeated France all wanted different things.

We’ll get into the nitty gritty in a minute. Just know for now that everyone in 1814 was aware a mishandled post-Napoleon peace could be catastrophic. Before the Sixth Coalition had even won, they’d agreed to a congress to hammer all their differences out.

Somehow, Metternich convinced them to hold it in Vienna.

The Congress of Vienna is one of the most important diplomatic gatherings in history. So, to make sure we can all get our heads around this extremely important event, we’re gonna take a quick detour now through the main players.

Ready for some hardcore learning, guys?!

The four key powers at the congress were Austria (obviously), Russia, Prussia, and Great Britain.

Since Austria was playing on their home turf, that meant putting Metternich in charge of everything. His goals were to maintain the balance of power, by ensuring post-war France didn’t get too weak, and Russia and Prussia didn’t get too strong.

Britain meanwhile sent over a guy called Viscount Castlereagh, who broadly agreed with Metternich about not destroying France, and not giving Russia and Prussia everything.

Prussia sent a delegation who were led from behind the scenes by the big boss, Frederick Wilhelm III. Ol’ Freddie’s grand plan was to hobble France and gobble up Saxony for Berlin.

Finally, Russia sent the head honcho himself.

Tsar Alexander I was the Congress’s wild card. Not only was he negotiating for Russia personally, he also wanted some odd things like giving the Poles their own country; a big deal since Prussia and Austria both owned Polish territory.

Although the table was designed for four people, there was one last guy in the mix.

Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, better known as just Talleyrand, was a French diplomat and weasel extraordinaire.

He was so adaptable that he’d served under Louis XVI, the French Revolutionary government, and Napoleon. And now he was in Vienna, claiming to represent the recently-restored French monarch, Louis XVIII.

Obviously, Prussia and Russia tried to laugh Talleyrand out the room. France had just been defeated! There was no seat for him!

But Metternich thought differently. Remember, he wanted to make France weaker than under Napoleon, but not so weak that it created a power vacuum Prussia might exploit.

So he teamed up with Castlereagh and got Talleyrand into the table’s new fifth seat.

Those are our players: Metternich for Austria, Castlereagh for Britain, Frederick Wilhelm III for Prussia, Alexander I for Russia, and Talleyrand for France.

All of them wanted different things, and all of them held the fate of Europe in their hands.

As the entourages of these great men descended on Vienna in the fall of 1814, the pendulum of history could have swung any one of a trillion ways.

Luckily for the conservative faction, Metternich had a plan.

The Congress of Vienna #2: Parties and Politics

The words “Congress of Vienna” are probably conjuring images of boring dudes in silly clothes sitting around tables and talking about impenetrable stuff.

Well, you couldn’t be more wrong.

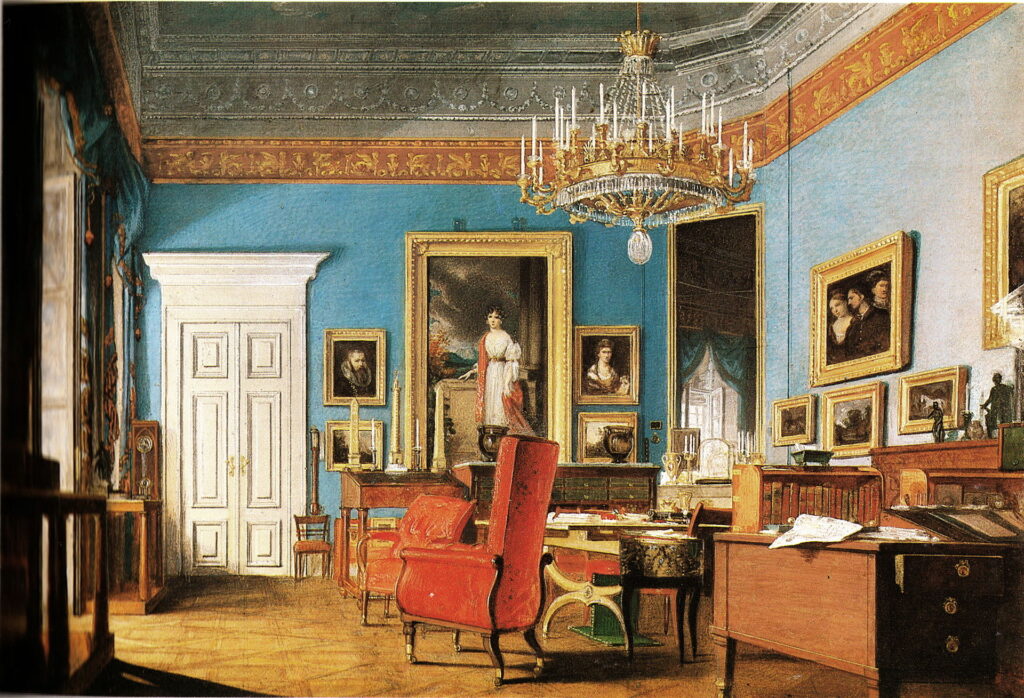

The Congress of Vienna was designed by Metternich to be the social event of the century.

There were parties almost every night. Glittering balls held by the glow of candlelight. Excursions to the greatest salons imperial Vienna had to offer.

The wine flowed freely. There was dancing. Romantic liaisons. Drunken affairs. One source we’ve seen even claims two of the top participants nearly got in a duel.

All of this debauchery wasn’t dereliction of duty. It was part of Metternich’s plan.

Remember, before he was Austrian foreign minister, Metternich was a womanizing party animal in Vienna. This was his territory.

He was the master of the quiet conversation over cigars in some smoky club. Of a well placed word on the dancefloor. Of buttering up someone over wine.

As the great men of history drank and danced and seduced their way across the capital, Metternich was working the crowd like a Silicon Valley hotshot.

He had the perfect allies for his endeavor.

Talleyrand was even more of a social butterfly than Metternich was. While they had their differences, the two were able to deploy a joint charm offensive to make sure Russia and Prussia didn’t demand France be carved up.

Castlereagh was even better. While he wasn’t a total bro, he was representing Britain, the country with the deepest pockets in the world. And Castlereagh, who saw eye to eye with Metternich on many major issues, wasn’t afraid to splash London’s cash to get what he wanted.

By February, 1815, the final shape of the congress was clearly visible.

Alexander’s plan to liberate the Poles had been bought off by offering him a chunk of Poland, while Prussia had agreed to make do with just three fifths of Saxony.

France, meanwhile, was to be pushed back into its pre-revolutionary borders, smaller but still powerful.

The Holy Roman Empire would be replaced with 39 states collectively known as the German Confederation, with Austria as its head, naturally.

There were other outcomes, too, including a guarantee of Swiss neutrality, and a commitment to free trade along Europe’s rivers, a clause cherished by Castlereagh.

But the big, headline news was the establishment of the congress system.

Spearheaded by Metternich, the new system would commit Europe’s great powers to meeting every year or so to discuss events and (hopefully) avoid war.

It also committed Europe’s powers to supporting monarchs and empires over nationalist movements.

This was perhaps Metternich’s biggest contribution to world history.

Metternich deeply believed that most Europeans were natural conservatives who preferred order and safety to the madness of revolution. And now everyone was agreeing with him. The Europe that emerged from the congress wasn’t some shiny new thing, but a place governed by king, family, and God.

It was everything Metternich had wanted, at least in the broader sense.

But, before he got it, there was one last nightmare to live through.

On March 7, 1814, Metternich was woken by an aide with some terrible news, not just for Metternich, but the entire congress.

Napoleon had escaped Elba. Not only that, he was on his way back to France. And the French people were rallying to his cause.

Such news could only mean one thing.

It was time for war again.

The Age of Metternich

When the news of Napoleon’s escape reached the congress, panic hit.

Within days, Metternich was making plans to depart Vienna. In France, the news caused the restored Louis XVIII to flee the country.

It was like waking from a nightmare to find you’re still dreaming. Europe was almost paralyzed, by the fear that Napoleon’s return would be even worse than his first reign.

Luckily, things didn’t quite work out like that.

The period of Napoleon’s return is known as the Hundred Days, because that’s roughly how long it lasted.

By June 18, 1815, the Seventh Coalition had forced the Battle of Waterloo. There, the British and the Prussians defeated the Petit Corporal once and for all.

Back in Vienna, the Congress hadn’t actually had time to disband by the time of Waterloo. Metternich himself was still in the city.

Which turned out to be fortunate when Prussia and Russia demanded France be made to pay for this latest insult. Metternich marshalled all his charm to make sure the Congress’s outcome remained the same as in February. Remarkably, the Hundred Days changed almost nothing.

In July, 1815, the Congress of Vienna finally disbanded.

With it went the era of revolution, the era of Napoleon.

In its place came the age of Metternich.

It was during this new age, as Europe was cautiously settling into a life without war, that Metternich became known as the Coachman of Europe.

Certainly, he was in the driver’s seat on many occasions. In 1819, he headed the Carlsbad Conference that committed the German Confederation to cracking down hard on freedom of speech, repressing liberal-national movements, and monitoring universities for sedition.

He also headed a string of Great Power conferences. So successful were these that Francis I made Metternich Chancellor of Austria.

However, it wasn’t all roses for Europe’s new driver.

Metternich wasn’t an idiot. He knew history was turning in favor of national movements, and he hoped to nip them in the bud.

Back home, he actually drew up a plan for Austria’s many ethnic groups to get their own parliaments. He hoped giving the Hungarians, Czechs, Italians, and so-on a shred of autonomy would inoculate Austria against further revolution.

But Francis shot him down. The emperor was all like “dude, I loved your secret police and crushing of free speech, but your later stuff, with all that national pride for Hungarians? Not a fan.”

Still, Metternich remained a big figure on the world stage. Even when his Congress system broke down over an argument with Britain about the Greek revolution, people clung to the basic ideas he’d outlined in Vienna.

In fact, by the 1830s, they were clinging harder than ever.

On July 27, 1830, a three day rebellion broke out in France that overthrew the restored royals and replaced them with the July Monarchy.

Barely a month later, Belgium exploded in a national uprising against the Netherlands.

Just three months after that, the Poles also went into rebellion against their Russian overlords.

And then 1831 rolled around and an Italian uprising forced the Austrians into armed intervention.

For those who’d started to doubt Metternich’s system, the multiple revolutions of 1830 – 1831 were a wakeup call. The rulers of Europe clamped down hard on nationalist feeling, which must have left Metternich feeling pretty vindicated.

But the revolutions could be seen another way, too. A sign that Metternich’s new system was built not atop firm ground, but a rumbling volcano.

It would only be a matter of time before that volcano erupted.

Decline and…

Even as Metternich’s stature grew on the world stage, he was starting to slip into the twilight of his career at home.

In the Viennese court, a dashing new liberal Bohemian prince, Franz Anton, Graf von Kolowrat, was suddenly the rising star, making Metternich look clumsy and slow and reactionary.

Metternich’s vanity was so offended by this that he started claiming every major policy initiative in Austria as his own, even the bad ones.

Not that Metternich made many good policies himself.

Take the issue of succession. Francis I’s eldest son Ferdinand was known by everyone to be intellectually disabled to the point of being unable to rule.

Francis had daughters and he had other sons, all of whom could have succeeded him, but Metternich was such a stickler for old fashioned, eldest son only succession that he actually talked Francis into not passing over Ferdinand.

And so it was that, on March 2, 1835, Ferdinand I ascended to the Austrian throne. Anyone hoping for a reformist ruler instead got a guy who simply couldn’t rule.

As the years dragged by, Metternich’s choices went from annoying to actively embarrassing.

In the late 1830s, he tried to revive his congress system, but no other great powers wanted to get involved.

Europe may have been shaped by Metternich’s system, but it sure as heck didn’t want to be ruled by him.

Not that all the things making Metternich unpopular were his fault.

The famine that gripped Europe in the 1840s, for example. Or the financial panic that tipped parts of the continent into recession.

What was Metternich’s fault, though, was the secret police network watching everyone at home. Arresting people for dissent, giving them nowhere to air their legitimate grievances.

Instead, people had to bottle everything up. Every pang of hunger. Every miserable indignity.

It was a recipe ripe for disaster. All it needed was an outside shock to send everything crashing down.

In 1848, that shock finally came.

No Country for One Old Man

If you study 19th Century European history – or, better yet, just watch our videos on the subject – 1848 is the year you’ll keep coming back to, because that’s the year that everything went bananas.

It started on February 23. That day a French government ban on holding banquets triggered a revolution that toppled the July Monarchy.

The crash with which the king fell was enough to bring Metternich tumbling down too.

By now, Metternich had been in power for nearly forty years. He was a symbol of everything that was old and cautious and conservative in Europe.

So, when news of the latest French Revolution reached Vienna, it made everyone hope Austria could change too.

Within days of the July Monarchy’s collapse, petitions were circulating through Vienna, demanding liberalization.

These petitions weren’t calling for Metternich’s head. They just wanted an end to his system. But since, under that system, the act of signing a petition was illegal, Metternich demanded all the tens of thousands of people who’d put their names down be arrested.

You know that old phrase “to shoot yourself through the foot?” This was Metternich accidentally blowing his own head off.

The short version of what happened next is that Vienna’s poor, liberal students decided to protest the government’s crackdown.

On March 13, 1848, a huge crowd gathered in the city.

Metternich demanded the crowd be crushed. The government’s anti-Metternich faction counselled peace, with the result that it was decided to maybe not crush the crowd, but… I dunno. Squash them? A little?

Whatever the correct metaphor, the cavalry were sent in at exactly the wrong strength. Wrong, because there weren’t enough of them to disperse the crowd, or do anything but spark a panic.

The panicked crowd attacked the cavalry, who fought back, killing five students. The firefight triggered a mass insurrection and the civil guard were called in.

Unfortunately, the civil guard took one look at the unfolding revolution and decided to side with the revolutionaries.

With the entire city in revolt, Metternich was given until 9pm to resign.

At first, Metternich refused. But, as the clock ticked down and the situation got uglier, reality finally dawned on the aging Chancellor.

Just before the stroke of nine, Metternich announced his resignation. The very next day, March 14, 1848, he fled into exile in London. The age of Metternich was over.

The next two years were crazy. As Metternich watched impotently from England, Ferdinand I was overthrown and replaced with Emperor Franz Joseph. The Hungarians and Italians went into rebellion. Prussia’s liberals revolted.

When the dust finally settled, though, one thing was clear.

Somehow, against all the odds, Metternich’s system was still standing.

Yep, the revolutions of 1848 basically failed. The old order was restored across the continent. Even France simply replaced the July Monarchy with the dictatorship of Napoleon III.

In 1851, Metternich was even allowed to return to Vienna. It was a triumph, of sorts, and the old statesman was soon back in the corridors of power.

But time was no longer on his side.

On June 11, 1859, Metternich’s health gave out. He passed away in Vienna, aged 86.

But while Metternich the man was gone, the system he created would stay in place for another 60 years.

In various guises, Metternich’s blueprint for Europe remained until WWI. It also succeeded in its mission to keep the peace.

Between the Congress of Vienna and WWI, the biggest war fought in mainland Europe was the Franco-Prussian War. Compared to the Napoleonic wars, or WWI and WWII, it was peanuts.

For all his faults, Metternich was a man who built something that lasted. He may have been vain, repressive, and sometimes actively stupid, but he was still the man who sat in Europe’s driving seat for decades. For better or for worse, our world would be very different without him.

(Ends)

Sources

https://www.revolutionspodcast.com/2017/05/608c-metternich.html

https://www.revolutionspodcast.com/2017/11/714-the-fall-of-metternich.html

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Klemens-Furst-von-Metternich

https://www.britannica.com/place/Austria/The-Age-of-Metternich-1815-48#ref984993

https://www.historytoday.com/archive/what-was-congress-vienna

Congress of Vienna: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b098bt3h

The Hundred Days: https://www.britannica.com/event/Hundred-Days-French-history