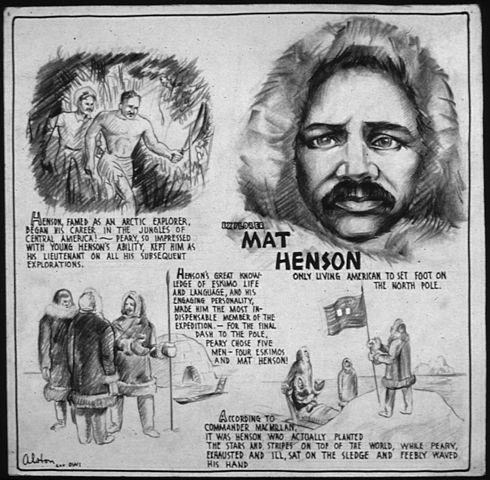

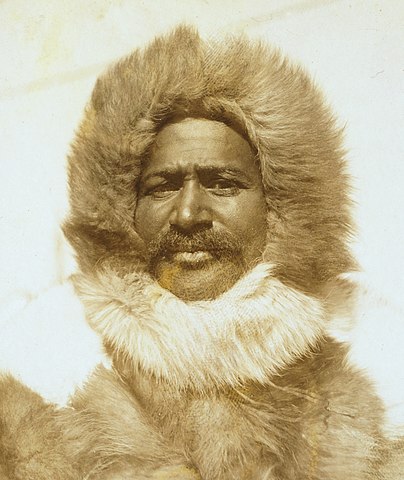

Matthew Henson was the first African-American to become a successful Arctic explorer. Not only that but, according to some accounts, he may be the first person to reach the North Pole. Even so, Henson rarely received credit from his contemporaries for his achievement, as most people preferred to praise a Robert Peary, who was better suited to their ideal image of an American explorer.

But inevitably, the pendulum swings the other way. It might have taken decades, but the world finally began to recognize that Matthew Henson was one of the greatest explorers in American history. He was awarded medals and honorary doctorates. He was put on a stamp, and had parks, schools, and even a glacier named after him. He was also reburied at Arlington National Cemetery. Matthew Henson is no longer simply an asterisk in somebody else’s career.

Early Life

Matthew Alexander Henson was born shortly after the end of the American Civil War, on August 8, 1866, in Nanjemoy, Maryland. Even before the abolition of slavery, his parents had been free Black Americans who made a modest living as sharecroppers. Despite their freed status, they still had to contend with racist vitriol and terror attacks from the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacists who began lashing out more frequently after the Confederacy lost the Civil War.

In an attempt to find a safer environment for their children, Henson’s parents left Nanjemoy and moved further up north to a town called Georgetown, near Washington, D.C. Unfortunately, both parents died in the years that followed, and while still a young boy, Matthew Henson found himself an orphan in the care of his uncle.

There was one event in Henson’s childhood that he later described as having a profound, inspiring effect on him. When he was 10 years old, he attended a ceremony to honor Abraham Lincoln, and one of the keynote speakers was Frederick Douglass, the former slave who became a prominent author, social reformer, and statesman. In his speech, Douglass urged young Black people to seek an education in order to combat racial prejudices and inequality. With these words in his heart, when he was barely 12 years old, Henson made his way to Baltimore, Maryland, which was steadily developing into a thriving port town. He found a job in 1878 as a cabin boy aboard a three-masted merchant ship called the Katie Hines under the command of Captain Childs.

Henson spent the next six years of his life on that vessel. Captain Childs took the young cabin boy under his wing and provided him with an education. Besides learning how to read and write, Henson also became an adept sailor and trained in a variety of skills, such as navigation and sailing, that would later prove useful in his career as an explorer. By the time he turned 20, Matthew Henson was a salty sea dog who had traveled to the Far East, North Africa, and the Arctic Seas.

Captain Childs passed away in 1887, prompting Henson to leave the Katie Hines and find a new vocation in life. The adventure bug had bitten him, but he did not have the means to go gallivanting to faraway lands on his own. And so, he went to Washington, D.C., and took a safe but boring job as a clerk for a furrier’s shop. But that did not last long…

Henson Meets Peary

Henson’s life changed forever one day in November 1887, when a Navy officer came looking to sell walrus and seal pelts brought from Greenland. He was Robert Peary, an engineer and explorer who had already made up his mind to become the first man to reach the North Pole.

At that point in time, Peary had just returned from his first expedition into the Arctic and had every intention of going back. However, he was still an active member of the United States Navy Corps of Civil Engineers, so he couldn’t just leave when he felt like it. Instead, he was due to travel to Nicaragua to conduct some surveys on possible routes for the proposed Nicaraguan Canal, which, as we know today, was never built.

While in the furrier’s shop, Peary and Henson got to talking. The officer learned of Henson’s exploits at sea and was impressed with his nautical experience, especially given that just a few years prior, the clerk was a poor orphan who couldn’t read or write. Peary recognized potential when he saw it, so he offered Henson a position as his aide for his upcoming surveying expedition to Nicaragua. Matthew Henson had developed a strong hankering for adventure, so such an opportunity was too good for him to pass up. He accepted the offer and, although neither of them knew it yet, began a partnership that would literally take them to the ends of the Earth.

The following year, Matthew Henson found himself in the rain forests of Central America as a personal assistant to Peary. Over the next two years of his life, Henson helped the officer create a map of Nicaragua’s tropical forests in search of possible routes for the canal. The former cabin boy performed admirably during the trip, and he returned to the United States as one of Peary’s good friends. He even helped Henson find a job as a messenger for the League Island Naval Yard in Philadelphia. But Henson already knew a life pushing pencils behind a desk was no life for him. Instead, he dreamt about going on adventures again, exploring the untamed lands of our world.

Indeed, it did not take long for such an occasion to arise. By 1891, Henson started building a regular life for himself – he had a steady job, was newly married to a woman named Eva Flint. However, Peary had received leave from the Navy, as well as financial support from the American Geographical Society, to continue his exploration of Greenland. He began assembling his team and at the top of his list was Matthew Henson, who eagerly accepted to serve as his “first man” once more.

The Lure of the Arctic

The North Greenland Expedition party set sail from New York in June 1891, aboard the SS Kite. At that time, much of the Arctic was a mystery to us, so their main mission was not to attempt to reach the North Pole, but simply to explore Greenland and see if it was an individual landmass or a peninsula.

As far as Matthew Henson was concerned, while he may not have had any formal training or experience in Arctic conditions, he learned by doing. He became a jack-of-all-trades, fulfilling numerous roles during his multiple trips to the frozen regions of the north. He served as navigator, mapmaker, hunter, fisherman, translator, solderer, carpenter, and dog handler.

Unlike most explorers, neither Peary nor Henson adopted an “I know best” attitude when it came to Arctic survival. They recognized the fact that the local Inuit people had tips and tricks to help them survive in the seemingly never-ending frozen wastes of the Arctic since, after all, they were the ones who managed to turn it into their home. They learned how to hunt, how to build igloos, and even how to dress in furs, even though other explorers considered the practice undignified and ungentlemanly.

While Peary was willing to use information from the Inuit to survive, his eagerness did not translate to affection or respect for them. But where Peary was horrid and quick to betray people he considered unworthy, Henson was compassionate. Henson knew firsthand how it felt to be treated like a second-class citizen and he had no intention of doing the same to others. He showed a genuine interest in Inuit culture and learned their language, which proved an invaluable asset when it came to securing their help for his expeditions. They called him “Mahri-Pahluk,” which was roughly translated to “Matthew the Kind One.” In turn, he wrote in his memoirs that “I have come to love these people. I know every man, woman, and child in their tribe. They are my friends and regard me as theirs.”

Going back to the actual expedition itself, it accomplished its goal, although not without hardships and sacrifices. The mission was marked by tragedy when the team’s mineralogist, John Verhoeff, lost his life after falling into a crevasse. The trip took a few months longer than expected because Peary suffered a leg injury but, in the end, the team crossed Greenland and proved that it was, in fact, one giant island. They made their way back to America in late 1892.

Call of the Frozen Wilds

This had been Matthew Henson’s first trip to the Arctic and it did well to showcase his skills and tenacity, and to solidify his position as Peary’s “first man” for the six more expeditions that they would undertake together over the coming 17 years.

The next voyage occurred the following year. This time, there were more men and a bigger ship, yet the mission was a failure due to terrible weather conditions. Henson fell ill during this trip after a “long race with death,” as he put it, and required months of rehabilitation to return to his old strength. On his way back in the summer of 1895, Henson swore never to leave his “happy home in warmer lands” again but, of course, we already know how that turned out. His oath was about as reliable as that of someone who promises never to drink again after waking up with a raging hangover.

One notable thing did happen during that expedition, though – Henson took in a local orphan:

“It was on this trip that I adopted the orphan Esquimo boy, Kudlooktoo, his mother having died just previous to our arrival at the Red Cliffs. After this boy was washed and scrubbed by me, his long hair cut short, and his greasy, dirty clothes of skins and furs burned, a new suit made of odds and ends collected from different wardrobes on the ship made him a presentable Young American. I was proud of him, and he of me. He learned to speak English and slept underneath my bunk.”

Two more missions to Greenland occurred in 1896 and 1897, which resulted in the team reaching the island’s most northern point and mapping it completely. This was only a secondary objective, though, as their main goal was to retrieve the gargantuan Cape York meteorite that had landed in the frozen wastes of the Arctic. The locals weren’t too happy with this, though, since they used the metal from the meteorites to make tools.

The Arctic team’s continued success increased the profile of the dynamic duo of Henson & Peary in the United States. That made it easier for them to secure funds in order to go on more missions. For their next trip, they intended to set a new Farthest North record. This is a term that has lost all value nowadays, but before anybody had reached the North Pole, Arctic explorers kept setting new records by traveling a little bit further each time, and the Farthest North referred to the most northerly latitude that had been reached by humanity.

If we take their word for it, then Henson’s team set a new Farthest North on two sequential voyages to the Arctic. The first one lasted for five years, between 1898 and 1902. This time, it was Peary’s turn to suffer the wrath of the Grim Destroyer, as Henson liked to call the merciless conditions caused by Mother Nature in the Arctic wastelands. The commander’s feet froze so badly that he lost nine toes to frostbite.

Understandably, this injury kept him on the shelf for a while, and Henson’s team didn’t return to the Arctic until 1905. This trip was shorter as they had obtained a state-of-the-art steamship dubbed the SS Roosevelt, which was powerful enough to make its way through the floating ice packs. The climax of this expedition was one of the rare occasions when Henson was not by the commander’s side, as the team got separated earlier during a storm. This actually proved problematic for Peary as he didn’t have anyone with him skilled enough in navigation to confirm that they had set a new Farthest North, but they claimed it anyway.

And this highlights the big problem with these expeditions. Nowadays, Robert Peary has what we might call an issue with credibility. The guy made a lot of bold claims and some of them might not have been true. We’ll get to the big one about reaching the North Pole in a minute, but his claims of setting new Farthest North records have also come under heavy scrutiny, and these doubts also tarnish the accomplishments of Matthew Henson by association.

Sitting on Top of the World

But enough of this “Farthest North” malarkey. From now on, it’s North Pole or bust, since this was the true goal that Matthew Henson and all other Arctic explorers of that time had in mind.

In 1908, it was finally time for the big one. On July 6, Henson set off on his seventh and final Arctic mission alongside his longtime companion, this time determined to make it all the way to the North Pole. They first traveled to Greenland where they picked up dozens of Inuit men, including Kudlooktoo who was eager to go exploring alongside his adoptive father, as well as hundreds of dogs and tons of meat. From there, they sailed to Ellesmere Island in Canada, where they made camp, and left for the pole in late February 1909.

The simplest tasks became complicated and exhausting when they had to be done under the brutal and relentless conditions of the Arctic. Even just soldering a few tins became a “job for a demon in Hades,” according to Henson:

“Worked all day soldering the tins of alcohol, and a very trying job it was… I tried to work with mittens on; I tried to work with them off. As soon as my bare fingers would touch the cold metal of the tins, they would freeze, and if I attempted to use the mittens they would singe and burn, and it was impossible to hold the solder with my bearskin gloves on.”

When the expedition started, the party consisted of 24 men, but only six were present for the last leg of the journey: Matthew Henson, Robert Peary, and four Inuit men named Ooqueah, Ootah, Egingwah, and Seegloo. Six almost turned to five when Matthew Henson slipped on a block of ice and fell into the icy cold water. In the Arctic, such an accident could easily have turned into a death sentence. In fact, that is exactly the outcome that befell one of Henson’s compatriots, Professor Ross G. Marvin, who drowned on this expedition while returning back to camp. Henson, however, did not share his fate, as he was saved by Ootah, who managed to grab the explorer by the nape of the neck, just like a sled dog, and pull him out of the water. The Inuit stripped Henson of his wet clothes and beat the water out of them. Then, following a wardrobe change, the hunt for the North Pole resumed as if nothing ever happened.

That was when the commander’s nasty side started to show itself because, in that moment, honesty, friendship, and teamwork, didn’t matter as much to him as much as becoming the first man to reach the North Pole. He realized the Inuit weren’t going to be a problem, but he would have liked to leave Henson behind, if he had any chance of making it without him. But he didn’t and he knew it. Matthew Henson was the one who took care of the dogs and the supplies, he was the one who knew how to fix the sledges, and he was the one who knew how to speak to the Inuit. If anything, Henson was the one who didn’t need Peary.

On April 6, 1909, the team made camp for the last time on their way to the pole. Up until this point, their camps were simply named “Camp Number One,” “Camp Number Two” etc., but they felt that something special was needed to mark this momentous occasion. Therefore, the commander took out an American silk flag and carefully planted it on top of their igloo, christening this location “Camp Morris K. Jessup” after one of their financiers. The six men went to sleep and woke up the next morning, ready to make the final march to the North Pole.

Ostensibly, the plan was for the faster Henson to scout ahead and then allow the Navy officer to overtake at the last minute and claim the glory of being the first to the North Pole. However, Henson’s team overshot their target, let’s say by mistake, but who knows, so when Peary finally caught up to them, Matthew Henson greeted him by saying “I think I’m the first man to sit on top of the world.”

According to Henson’s journal, the mood became decidedly frosty from that point on, even by Arctic standards. Henson wrote:

“From the time of my arrival at the Roosevelt, for nearly three weeks, my days were spent in complete idleness. I would catch a fleeting glimpse of Commander Peary, but not once in all of that time did he speak a word to me. Then he spoke to me in the most ordinary matter-of-fact way, and ordered me to get to work. Not a word about the North Pole or anything connected with it…”

Even though neither one said anything about it, they both knew that the partnership they’ve had for over 20 years had disintegrated.

Life after the Arctic

Back home, Peary immediately went to work to ensure that he was the one who enjoyed all the fame and glory and not Matthew Henson. This did not prove difficult. Despite his decades of experience and success, racial prejudices against Henson were still pervasive, and the world at large was more than happy to dismiss him simply as a mere sidekick to the commander. Even newspapers of the day decried the fact that Peary gave the honor of reaching the North Pole to a Black man, instead of one of his White companions, such as the ship’s captain, Robert Bartlett. Only other explorers who knew Matthew Henson personally understood how indispensable he had truly been to the success of the mission, and that Peary didn’t take him by choice, but because he could not have done it without Henson.

Even after he published his own memoir in 1912, titled A Negro Explorer at the North Pole, Henson still went mostly ignored. However, karma’s a you-know-what and Peary encountered a completely different and unexpected opposition to his claim – Frederick Cook, a man who accompanied them on Henson’s first trip to the Arctic as the team’s surgeon. He also claimed to have reached the North Pole, and he said that he did it first. This triggered an intense debate over who was telling the truth, if, indeed, any. Whether by choice or by force, Matthew Henson mostly stayed out of the controversy, although he disbelieved Cook’s story, feeling that he was too soft to succeed in such a grueling mission.

As far as Henson was concerned, he lived a quiet, unassuming life after his Arctic days were over. He never tried to go on another mission, both because he did not want to do it without his long-term companion and because he felt that he already accomplished what he set out to do in the Arctic. Henson found a job with the U.S. Customs House in New York City on the recommendation from President Teddy Roosevelt himself and spent almost 30 years working there. He had married again to a woman named Lucy Ross in 1907, and had an Inuit concubine named Akatingwah while in Greenland, who gave him his only biological child, a son named Ahnaukaq. This fact, however, was not publicized until the 1950s, after Henson’s death.

Unfortunately, in the decades following his historic trip to the North Pole, Matthew Henson saw his accomplishments swept under the rug and forgotten, while his former partner was made an admiral and received multiple medals and honors. It wasn’t until 1937 that Henson was made an honorary member of the Explorers Club of New York, and a decade later he was awarded a medal by the U.S. Navy for his efforts. Matthew Henson’s final tribute in his lifetime came in 1954 when President Dwight Eisenhower invited him to the White House to receive a special commendation for his work as an explorer.

Matthew Henson died a year later, on March 9, 1955, in the Bronx, aged 88. In 1988, following a special exception granted by President Ronald Reagan, Matthew Henson and his wife Lucy were reburied at the Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. The gravestone’s central image showed Henson and the four Inuit men who accompanied him to the frozen end of the Earth – Ooqueah, Ootah, Egingwah, and Seegloo. Thus, some long-deserved recognition was finally granted to five intrepid explorers who persevered and triumphed in the face of adversity, both from Mother Nature and their fellow men.