Sometimes history throws up a figure so dynamic, it seems like they’ve witnessed every important event of their era. In the case of the Marquis de Lafayette, he didn’t just witness these events. He often caused them. Born in the latter half of the 18th Century, Lafayette’s life reads like a spec script for an epic Oscar Winner. As a teenager, he fought in the American Revolutionary War. As a young man, he spearheaded the first phase of the French Revolution; before fleeing a death sentence at the guillotine. He was friends with George Washington, Louis XVI, Thomas Jefferson, and Simon Bolivar; and was instrumental in both the downfall of Napoleon, and the revolution that overthrew France’s last Bourbon king.

In short, Lafayette was a dude who packed a lot into his seven decades. But while he remains famous for his role in the Revolutionary War, how much do we know about the rest of his life? About the man who was at the forefront of not one but two French Revolutions? Join us today as we peek inside the life of the Marquis de Lafayette – the man who changed the fate of both America and Europe forever.

Born to Fight

When the Marquis de Lafayette was born on September 6, 1757 in France, it was into an old noble family of soldiers.

In fact “the Marquis de Lafayette” is an aristocratic title. But since his real name was Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette; we’re just going to refer to him as “Lafayette” for the rest of this video. But while young Lafayette was both pampered and connected – he learned to ride horses in the company of three future kings – life wasn’t exactly easy.

When he was barely two, his father was killed fighting in the Seven Years’ War. By the time he turned 13, in 1770, he’d also lost his mother and his grandfather. Still, the gigantic fortune he inherited must’ve softened the blow.

Come 1774, Lafayette was married, and a courtier at the Versailles of newly-crowned king Louis XVI. But Lafayette came from fighting stock. The pompous luxury of Versailles bored him. He wanted to win glory as a soldier. To go and fight in some great war somewhere.

Luckily for him, one of the greatest wars in history was about to blow up.

On April 19, 1775, the growing animosity between Britain and its American colonies finally exploded when a bunch of soldiers and local militiamen clashed at the towns of Lexington and Concord. It was the opening salvo of the Revolutionary War, often referred to as “the shot heard around the world.”

Over in France, the Marquis de Lafayette certainly heard it.

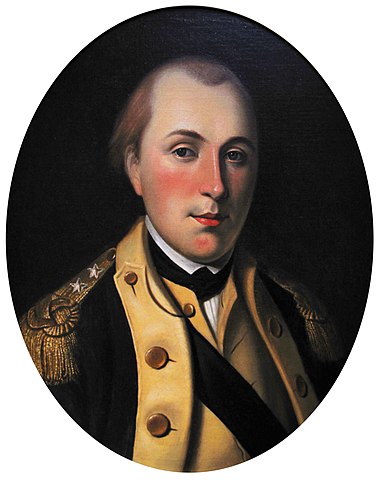

By summer of 1777, 19-year old Lafayette had become so obsessed with the war raging in America that he decided to go join. That July, he arrived in Philadelphia, where he presented himself to the Continental Congress.

The Congress took one look at this scrawny teenager with no battle experience, and told him in olde timey slang to go perform an act of intercourse upon his own buttocks. At least they did until the Marquis declared he was willing to fight for free, at which point the calculation changed.

In the summer of 1777, the war was not going well for the Americans.

Smallpox was devastating their ranks, they’d only won symbolic victories – as opposed to useful ones – and the British were on the verge of capturing Philadelphia.

Right now, Congress would take any free help they could get.

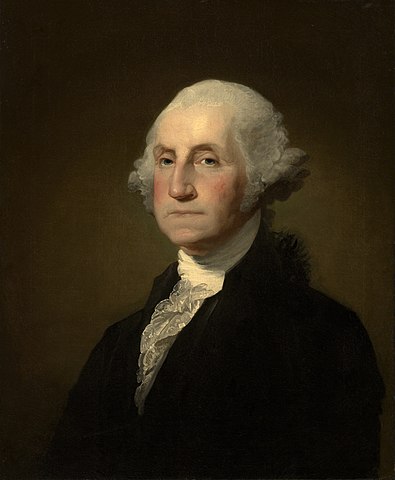

Portrait of George Washington (1732–99)

Which was how George Washington found himself, on July 31, face to face with a rich French teenager who’d somehow been given the rank of major-general. Washington had been saddled before with useless European royals who came over to fight because they were rich and looking for adventure.

Invariably, they turned out to be useless even as cannon fodder. There was no reason to assume this new one would be any different.

But Washington’s snap judgement would turn out to be wrong.

Over the month of August, 1777, Lafayette rose from being someone Washington couldn’t stand the sight of, to his personal favorite. It helped that Lafayette was brave in battle, and a natural leader of men. It likely helped even more that both Washington and Lafayette were looking for someone to fill an emotional hole in their lives.

As many have noted before, Lafayette wound up becoming the childless Washington’s surrogate son.

At the same time, Washington seems to have filled the father-shaped void in Lafayette’s life. The two became incredibly close in a matter of weeks. When Lafayette was wounded in the Battle of Brandywine that autumn, Washington had his personal physician attend to the lad.

It was the start of a long relationship that would hugely influence both men.

It would also hugely influence the course of American history.

The Hero of Two Worlds

Under Washington’s tutelage, the Marquis soon bloomed into a great general. He pulled off an impossible retreat from Barren Hill, and was instrumental in harrying Benedict Arnold’s forces in 1781. More-importantly, though, he soon became the fledgling nation’s best ambassador.

In 1779, Lafayette returned to France to drum up support for the American revolutionaries.

Although Louis XVI didn’t need much convincing that screwing with Britain was très bien, it’s still impressive how much aid the Marquis returned with. In April, 1780, Lafayette triumphantly reported to Washington that 6,000 infantry and six ships were on their way from France.

Yet his most-impressive moment of all would come in 1781.

That summer, in the run-up to Yorktown, Washington ordered both Lafayette and “Mad Anthony” Wayne to head south into Virginia. Both their troops mutinied at the news of yet more fighting. But, while “Mad Anthony” lived up to his reputation by executing the ringleaders and displaying their bodies, Lafayette took a different approach.

He told his men they were free to go.

He leveled with his soldiers, saying they were heading into danger, that many of them wouldn’t make it, that the British might annihilate them all. But he also reminded them what they were fighting for. Why they’d signed up to be here in the first place; what this new nation could represent.

In the wake of Lafayette’s speech, nearly all of the deserters returned. Lafayette rewarded them by spending his own money on new boots and blankets.

And then, as one, they marched down toward Yorktown and into history.

It was Lafayette’s troops who were partly responsible for trapping Lord Charles Cornwallis at Yorktown in late July. Once Cornwallis surrendered on October 19, it was effectively the end of the Revolutionary War. In the aftermath of the British having their asses handed to them, Lafayette was hailed as “the hero of two worlds”.

Many of the states made him an honorary citizen. Returning to France, he was promoted to maréchal de camp (or brigadier general).

It was a proud time in the Marquis’s life.

Not yet 25, he’d helped engineer the success of the American Revolution; at that time the most-significant revolt in living memory.

Little could he have known that this was just a warm-up for the main act.

Revolution, Part One: Paris is Burning

In the latter half of the 1780s, France made a grisly discovery. It was broke. The royal treasury was empty. Credit lines maxed out. In the face of a countrywide financial collapse, Louis XVI made a fateful decision.

He summoned the Estates General.

The Estates General was a meeting of France’s three “estates”: the aristocracy – to which Lafayette belonged – the Church, and the commoners. Generally, French kings avoided calling the Estates General. The last meeting had been in 1614, 174 years previous.

But if Louis wanted to head off the brewing crisis, he had no choice.

On May 4, 1789, 1,200 representatives of the three estates convened in Paris. Among their number was Lafayette, elected as a deputy of the nobility. But while Lafayette was lumped in with all the other French fancypants; he wasn’t just another posh twit.

He’d spent years immersed in the ideals of American independence.

And now he was gonna bring them to France whether his countrymen liked it or not.

The Estates General officially opened on May 5, and quickly devolved from a meeting about state finances, to a massive pile-on in which everyone took turns bitching about the ancien regime. The Commoners were fed up with living in a convoluted, backwards France filled with pointless privileges and regressive taxation.

But they were also fed up with being outvoted and pushed around by the other two Estates.

So, on June 17, the Third Estate’s deputies declared themselves a sovereign National Assembly.

The whole thing was organized with the help of Lafayette; one of the few nobles who joined the Assembly. The king tried to counter by having the meeting hall locked, but the Assembly repaired to a tennis court, where everyone took an oath not to disband until they’d forced a liberal constitution on France.

And they had just the guy to write it.

With help from his old buddy, Thomas Jefferson, Lafayette drafted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen – one of the most-important documents ever written. In it, Lafayette set out his conception of universal rights, with a strong emphasis on personal liberty.

Although the Assembly would redraft his work before adopting it, Lafayette’s ideas still heavily influenced the final version.

But the Marquis’ effects on the French Revolution weren’t gonna stop with one document.

Three days after Lafayette presented the Assembly with his draft, a Parisian mob stormed the Bastille and the Paris Hotel de Ville – a fancy name for city hall. The morning after, representatives of Paris’s 60 districts convened on the Hotel and declared the creation of their own National Assembly: the Paris Commune.

As part of this shakeup, a city-wide National Guard was formed to replace the king’s men.

And who could be a more natural fit as commander of that Guard than the hero of two worlds?

On July 17, a reluctant Louis came down from Versailles to meet the man now heading the army that effectively controlled Paris. He was taken inside the Hotel de Ville, where someone pinned a revolutionary red and blue cockade on his chest.

Lafayette saw the king wearing the cockade and had a flash of inspiration.

Taking some white cloth – white being the color of the Bourbon monarchy – he added a strip to the king’s cockade. Then Lafayette and Louis XVI both went out onto the balcony, where the gathered Parisians shouted “long live the king!”

It was the birth of the Tricolour, the revolutionary symbol that is still the flag of France.

It was also, the Marquis hoped, the birth of a liberal republic. One in which the king was a figurehead, and the actual governing done by middle class business-types.

But the Marquis would be proven wrong on this one.

Far from wanting the king as a figurehead, the people of Paris were soon going to realize that they preferred their kings without a head at all.

Revolution, Part Two: Terror Reigns

The wheels on Lafayette’s plan started coming off that same autumn. On October 5, a riot over bread prices in Paris turned into an army of heavily-armed, very unhappy women.

The next day, they marched on Versailles, some 19km distant.

When Lafayette got word, he first tried to stop them, only to realize his guardsmen would mutiny if he did so. So the Marquis changed tack and rode out at the head of the angry women, nominally there to “protect” them, but actually wondering what the hell he was gonna do. When the mob arrived, Lafayette zipped inside the palace to try and convince Louis to announce his support for the Assembly’s liberal reforms.

But while he was talking, the crowd invaded the palace, where they killed two guards and stuck their heads on pikes. The situation getting desperate, Lafayette forced the king out onto a balcony to say his piece.

It was a tense moment. The crowd could’ve easily broken in and lynched not just Louis, but Lafayette, too.

Luckily, though, the plan worked.

The crowd began hollering “long live the king!” then offered to escort Louis and his family back to Paris. Well, we say “offered”. More like they “ordered” him, on the strict understanding that saying no would result in his head being stuck on a pike too.

And so the Royal family were escorted back to the capital, and effectively imprisoned in the Tuileries Palace.

But Lafayette had brought them time. Not only that, he’d brought himself influence with the mob.

From now on, he was going to be at the very forefront of the French Revolution.

For the next year and a half, that’s exactly where Lafayette stood. As the Assembly abolished feudalism, and stripped powers from the aristocracy, he was the most-visible symbol of the changes.

Under his watch, the bourgeoisie gained new rights. It was the mannered, Liberal revolution of Lafayette’s dreams.

Sadly, it was already slipping out of his grasp.

The Marquis’ fall from grace came on July 17, 1791.

On that day, the Paris National Guard opened fire on a group of protestors demanding the king’s resignation. 50 people were injured or killed. As commander of the guard, Lafayette’s popularity plummeted. He resigned his post, had himself transferred into the army.

With Lafayette sidelined, the radical elements began gaining in power.

By April, 1792, the crazies were so in ascent that France declared war on Austria, beginning a series of conflicts that would wrack Europe for a quarter of a century. Sent to lead one of the three main armies, Lafayette returned from the front to Paris twice to denounce the radicals and plead for common sense.

Alas, no-one was listening.

On August 10, 1792, a working class revolt in Paris overthrew the monarchy, and brought the hyper-radical faction headed by Robespierre to power. Seeing which way the winds were blowing, Lafayette abandoned his post and crossed the lines into enemy territory.

Just in time, too.

Before news even arrived of his desertion, the Assembly declared Lafayette a traitor; effectively an invitation to come and dance with madame guillotine.

But although Lafayette escaped with his head, his nightmare wasn’t over.

Arrested by the Austrians, the Marquis spent the next five years shunted between jails, gloomily listening as the news from France got worse. Six months after Lafayette crossed the lines, Louis was guillotined, ending Lafayette’s hopes of a constitutional monarchy.

Another six months after that and the Reign of Terror began.

Although his former comrades in America begged for his release, there was nothing to be done. Lafayette had been sentenced to rot in a cell, and rot he would. Well, at least for a while. Because in just a few short years, a great man would ride to the Marquis’ rescue. Perhaps the greatest man in European history.

His name? Napoleon Bonaparte.

And he would transform France’s fortunes.

The Age of Empire

During Lafayette’s years in prison, the situation in France gradually reversed. On July 27, 1794 – also known as 9 Thermidor, Year II – Robespierre was overthrown and subsequently guillotined. In the wake of the Thermidorian Reaction, the Directory rose to power.

Corrupt and reactionary, the French Directory would last a mere four years before it, too, was overthrown.

But luckily for our story today, it did two very important things in those four years.

The first was to promote a promising young general named Napoleon, and get him to invade Austria to force an end to the war. The second was to insist any peace deal included the freeing of the Marquis de Lafayette.

On September 19, 1797, Lafayette walked free of his Austrian prison.

At first, the Marquis was all like “man, isn’t this Napoleon dude awesome?” but soon he was feeling significantly less cool about France’s new hero.

He was worried about Napoleon’s ambition, his lust for power.

But if Lafayette thought Napoleon’s ambition was a bit much now, wait until he saw what happened next. On November 9, 1799, Napoleon overthrew the Directory in the coup of 18 Brumaire. In place of the Directory, he installed himself as First Consul of France.

Dramatic as this was, though, Lafayette’s attention was busy elsewhere.

On December 14, George Washington passed away in Virginia. Having already lost his real father, the Marquis had now also lost his surrogate one.

This may help explain why Lafayette spent most of 1800 out of the picture. It wasn’t until autumn that Napoleon tried courting the hero of two worlds. The incentive was an ambassadorship to America. When Lafayette gently sounded Napoleon out on France becoming a democracy, the reply he got wasn’t encouraging.

So Lafayette turned down the post. Began speaking out against Napoleon.

In May of 1802, he was one of the lone voices to vote against Napoleon becoming First Consul for life, declaring:

“I cannot vote for such a magistracy until public liberty has been sufficiently guaranteed.”

But that guarantee never came. Lafayette retired from public service that same year. Although Thomas Jefferson offered to make him governor of newly-purchased Louisiana in 1803, Lafayette refused.

He also refused another offer from Napoleon, to be given “an elevated rank in the Legion of Honour.”

When the First Consul finally had himself named Emperor Napoleon on December 2, 1804, Lafayette seems to have given up on politics entirely. But while he’d stay out of the game for nearly a decade, he wouldn’t be able to resist coming back.

In April, 1814, the War of the Sixth Coalition ended with Napoleon abdicating and being sent into exile on the island of Elba.

In the wake of the empire’s collapse, the Bourbon monarchy was recalled to the French throne in the portly shape of Louis XVIII. The site of yet another fat Louis on the throne wasn’t exactly music to Lafayette’s soul. In his heart, he was still a child of the American Revolution, and would prefer a world without royals.

But, when forced to choose between another Bourbon king and Napoleon’s continued reign, the Marquis knew who he preferred.

On March 1, 1815, Napoleon escaped his island prison and returned to France.

Louis XVIII fled and the emperor marched on Paris, kickstarting a period known as the Hundred Days. Disgusted at Napoleon’s resurrection, Lafayette left retirement. He took up a post in the Chamber of Deputies, determined to become a lone voice against the emperor’s tyranny.

Instead, he wound up helping end his rule for good.

In the aftermath of Waterloo that June, Napoleon’s brother came to the Chamber to rally support for the emperor. Instead, he was forced to listen as Lafayette made a barnstorming speech laying the deaths of millions at Napoleon’s feet.

It’s said many of the younger deputies hadn’t realized until that moment that Lafayette – by now pushing 60 – was still alive. Regardless, the speech worked. In its aftermath, Lafayette led the charge for Napoleon’s second abdication.

On June 22, the emperor obliged.

Before Napoleon went into his second exile, the Marquis went to the Tuileries Palace to thank him.

There, Napoleon met him not with anger, or outrage… but with a wry smile.

You got rid of me, we like to think that smile said, but now the Bourbons are back, the kings you fought so hard to rid France of 25 years ago.

What are you gonna do now, hmm?

But Lafayette would soon have an answer.

Although no-one in 1815 could’ve realized it, the Marquis was destined to extinguish the Bourbon line once and for all.

The Last Revolution

The next ten years were a decade of disappointment for Lafayette. Initially willing to give Louis XVIII a chance, he soon became convinced the king needed to go. Starting around 1819, Lafayette began clandestinely funding liberal plots to overthrow the monarchy. But they all went nowhere.

By 1824, the Marquis was frustrated, and all too aware that the Bourbons were catching onto his schemes.

He needed a break. A place to lie low and recalibrate. A place where he didn’t carry all the baggage he did in France.

Luckily, that place was only a boat ride away.

That year, President James Monroe wrote to Lafayette, asking if he’d attend celebrations of America’s 50th anniversary. By now, Lafayette was the last surviving major general of the Revolutionary War; one of the last links Americans had to their nation’s birth.

Lafayette accepted.

On July 13, 1824, Lafayette left France to begin what would become a 13-month victory tour of all 24 US States. Wherever he went, he was feted. Across 9,600km, he was cheered, welcomed, and honored. It was a colossal outpouring of love. Towns were renamed after him – if you live in one of the dozens of places in the US named “Lafayette”, chances are it was named during this journey.

By the end, the Marquis had seen Jefferson for the last time, and visited Washington’s grave.

He’d even met Simon Bolivar’s nephew, who was studying in the US.

When Lafayette heard the great South American revolutionary had been inspired by his exploits, he decided to write to him. And that’s how Bolivar and Lafayette wound up becoming pen pals in the last years of their lives.

By the time Lafayette left America, on September 6, 1835, he was pretty much all loved out.

And that was probably for the best.

Because France was by now a pretty unlovable place. Back in 1824, Louis XVIII had died and the throne passed to his brother, Charles X. But while Louis had been a royal pain, Charles was a throbbing dick. Convinced of his divine right to rule, he tore up the last shreds of French liberalism, replacing it with a hardcore Catholic, hardcore Conservative, absolute monarchy.

It was almost like the Revolution had never happened. Charles was trying to turn back the clock to 1789.

Lafayette’s last great act would be ensuring he didn’t succeed.

On 26 July, 1830, Charles published something called the Four Ordinances; effectively a royal coup. They suspended freedom of the press, stopped almost everyone in the nation from voting, and removed the last checks on the king’s power.

Charles thought it would be fait accompli. Instead, it became a revolution. For Parisians, the Four Ordinances were the last straw.

They rose up spontaneously, driving Charles’s forces into retreat in just three days – known as the Three Glorious Days. But while the Marquis and his liberal friends were happy to see Charles go, they were less happy at the thought of all these angry Parisians suddenly wheeling out the guillotine.

So they decided to get out ahead of the revolution while they still could.

Conscripting Charles’s cousin, Louis-Philippe, they had him ride into Paris draped in a Tricolour, right through the revolutionary crowds, all the way to the Hotel de Ville. There, a waiting Lafayette took the future king up to the balcony – just as he had done with poor Louis XVI all those decades ago – and, waving the Tricolour, the two men embraced.

At the sight of the hero of two worlds bestowing his blessing on the new king, the crowd went nuts.

With that one kiss, Lafayette ended the July Revolution. A few days later, Louis-Philippe was made head of a liberal, business-friendly monarchy with proper checks and balances. It was the moment the Marquis had dreamed of since 1789. A liberal system for France in which the king was mostly a figurehead, and individual freedoms secured.

But you know what they say.

Be careful what you wish for.

Over the next four years, Lafayette grew increasingly disillusioned with the July Monarchy, and its slow bumbling toward authoritarianism.

By the end of his life, he was one of Louis-Philippe’s harshest critics, a constant thorn in the king’s side.

Luckily for the new king, Lafayette wouldn’t be around much longer. On May 20, 1834, aged 76, the Marquis de Lafayette died in Paris. Although many mourned him, Louis-Philippe refused to allow eulogies at his funeral, even having him buried under armed guard.

It was a bitter end to an extraordinary life.

In his seven decades on this Earth, Lafayette had repeatedly found himself at the center of events that changed world history. The Revolutionary War, the French Revolution, the Downfall of Napoleon… these are all hugely significant events that would’ve played out very differently without the Marquis.

And then there are the documents he left behind. The modern French constitution still incorporates the Declaration on the Rights of Man, over 200 years after Lafayette wrote it.

But it’s not just what he did or who he met that makes the Marquis impressive.

It’s what he stood for.

All his life, Lafayette was a tireless champion for individual liberty and freedom from tyranny. These were causes that took him to the battlefields of America; into the heart of France’s revolution; even into an Austrian prison. Time after time, people asked him to sell out. Napoleon. Louis XVIII. Louis-Philippe. And each time, the Marquis never wavered in his beliefs.

It’s often said that, for evil to succeed, all it takes is for good men to do nothing.

The life of the Marquis de Lafayette takes that saying to its opposite extreme. It shows what can succeed when a good man decides to do something. To stand up, to act, to be counted.

When a man like Lafayette decides to do that…

…well, then he can change the world.

Sources:

Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Marquis-de-Lafayette

Biography: https://www.biography.com/political-figure/marquis-de-lafayette

Washington and Lafayette: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/washington-amp-lafayette-162245867/

Revolutionary War timeline: https://www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/american-revolution-history

Summoning of the Estates General: http://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/history/key-dates/summoning-estates-general-1789

Tennis Court Oath: https://www.britannica.com/event/Tennis-Court-Oath

Lafayette and tricolour: http://rodama1789.blogspot.com/2017/07/who-invented-tricolour-cockade.html

Women’s March on Versailles: https://www.thoughtco.com/womens-march-on-versailles-3529107

Imprisonment in Austria: https://www.americanheritage.com/imprisonment-lafayette

Lafayette and Napoleon: https://shannonselin.com/2015/03/napoleon-and-marquis-de-lafayette/

Napoleon timeline: https://www.napoleon.org/en/history-of-the-two-empires/timelines/from-life-consulship-to-the-hereditary-empire-1802-1804/

Hundred Days: https://www.britannica.com/event/Hundred-Days-French-history

Lafayette returns to America: https://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/lafayette-returns-america/

Letters to Bolivar: https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/venezuela/article70333652.html#:~: