The year is 30 BC. In the grand Egyptian capital of Alexandria, panic is sweeping the streets. A mighty Roman fleet is bearing down on the city, bringing fire, destruction. In a half-finished mausoleum, Cleopatra and her lover Mark Antony await the inevitable. Antony’s stomach has already been sliced open, and now the great general is merely waiting to die. As Roman boots pound the streets, the wounded man orders one last cup of wine. Then, as his lover looks on, he offers her a final toast before everything goes black.

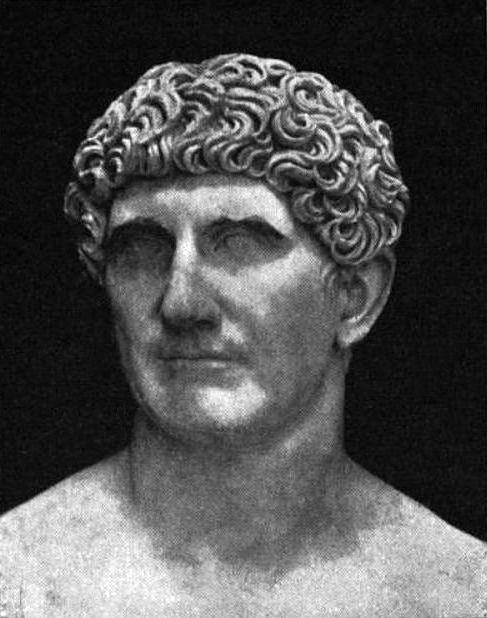

The deaths of Mark Antony and Cleopatra are some of the most famous in all history. Breathlessly poured over by the ancients, turned into high tragedy by Shakespeare, the extinguishing of their love has been fodder for countless adaptations. But how much do most of us know about Mark Antony? How did he come to be Cleopatra’s lover, and how did the two wind up dying in misery, their dreams just so much ash? Today, Biographics is uncovering the story of Mark Antony; the man whose death heralded the birth of an empire.

The Boy and the King

One of the most interesting things about Mark Antony’s early career is that it basically reads like a “greatest hits of ancient history.”

Seriously, over the next six minutes, you’re gonna watch him meet Cleopatra, Julius Caesar, and the future emperor Augustus; and see him cross Rubicons and help conquer Gaul. But perhaps the most remarkable thing about a guy who spent, like, his entire life at the epicenter of history is just how unremarkable he seemed destined to be.

Born on January 14, 83 BC, Antony came from a family that was rich, but not respected. His father was a famously incompetent general. While his mother was a cousin of Julius Caesar, Caesar in 83 BC was just some 17-year-old who nobody expected to one day become a dictator.

It also didn’t help that Antony’s early life was remarkably dissolute. As a teenager, he fell in with a guy called Curio, who was all about blowing Antony’s money on whores, games, and gold. As a result, Antony wound up 250 talents in debt before he was 20, a sum that’s equal to something like $5 million today.

So Antony skipped town, heading to Greece to “study philosophy”.

You know those guys who just keep partying after college until it becomes kinda embarrassing? That was Mark Antony in Greece.

But his bohemian ways did give him something more than an endless hangover. They left him with an abiding love of Hellenistic culture. Finally, when Antony was 26, a Roman general called Aulus Gabinius convinced him to get his life in shape by joining the war in Syria. Antony agreed, perhaps hoping to find more places he could get drunk in.

What he found instead was his vocation.

It turned out Antony was great at war. As a cavalryman in Syria, he distinguished himself again and again. Likewise in Egypt, where the Romans had been invited to crush revolts against Ptolemy XII.

It was while doing all that revolt-crushing that Antony was introduced to one of Ptolemy’s teenage daughters.

The girl was only 14. But something about her charmed the young soldier, hypnotized him.

The name of that teenage girl? You guessed it: Cleopatra.

But this is just a quick cameo. Antony didn’t immediately shack up with Cleo, but instead went off to fight in Gaul – a place roughly analogous to modern France and Belgium. There, he served under the second of the great figures who’d shape his life: Julius Caesar.

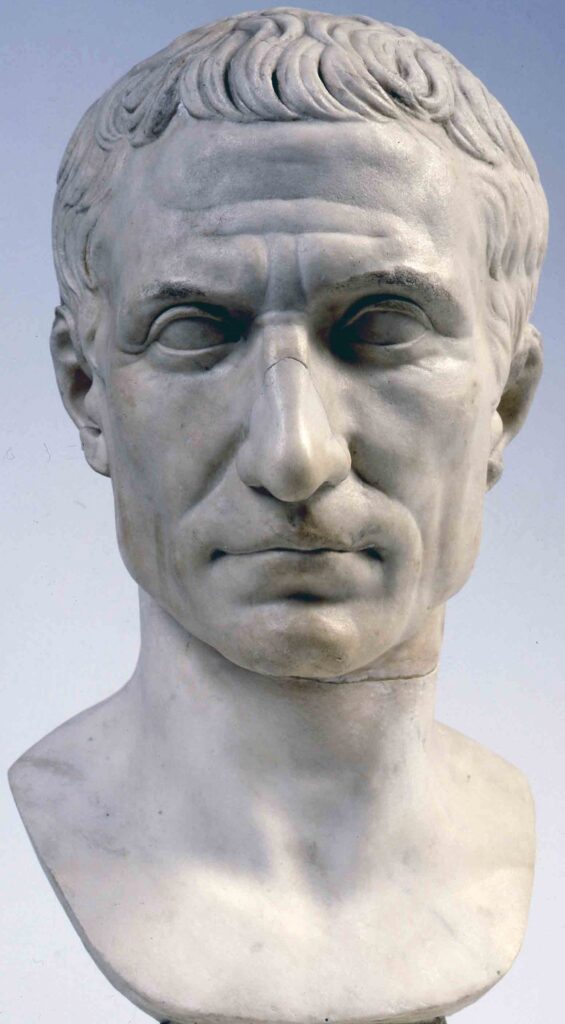

By 54 BC, Caesar was no longer a 17-year old nobody, but a great general and, along with Pompey and another dude you don’t need to bother remembering, a member of the First Triumvirate that called the shots in Rome.

In short, he was well on his path to greatness. Which made Antony’s arrival perfect timing.

Under Caesar, Antony continued to excel at warring.

Not only that, he also excelled at just being a soldier; drinking with his men, eating alongside them, and earning himself a devoted following among the rank and file. By 50 BC and the end of the conquest of Gaul, Antony had proven himself so many times over that Caesar sent the 33-year old back to Rome to take the office of tribune.

But while being tribune would’ve been a fitting cap for many Romans’ careers, Mark Antony was just getting started.

In barely a year he was going to be ruling the city itself.

The Man and the Dictator

When Antony arrived, Rome was in turmoil.

Caesar’s fellow Triumvir Pompey was trying to force the great general to give up his army, and there were frequent clashes in the streets between the their supporters.

Onto this political dumpster fire, Antony poured a cascade of gasoline.

In the Senate, Antony hooked back up with his old buddy Curio – now a Caesar supporter – and began goading Pompey.

Things came to a head when Antony suggested Pompey get out of politics for the good of the Republic, leading to so many death threats that Antony was forced to flee – all the way back up to the frontiers of Italy, where Caesar was camped across a river called the Rubicon.

You know the phrase “crossing the Rubicon”? It means to commit to a course of action from which there’s no going back. We have this phrase because, in 49 BC, it was forbidden for a commander like Caesar to march his troops over the river and into Italy.

But when Caesar heard Antony’s story, he decided he had no choice. So he elevated Antony to his second in command, and then both literally and figuratively crossed the Rubicon.

Mark Antony, everyone. Witness to both major historic events and the coining of everyday phrases.

The news of Caesar’s crossing caused Pompey to flee Rome.

This was great from the perspective of Caesar being able to waltz in and have himself declared dictator, but less good from the perspective of Caesar now having to track down his rival. But before Caesar gave chase, he put the city under Antony’s control.

As supreme administrator of Rome itself, Antony was almost comically useless.

Plutarch writes that “he was too lazy to pay attention” to running the city, and that’s being generous. Antony was so negligent he almost caused a revolution. When Caesar returned from fighting Pompey in Egypt in 46 BC, he was so stunned by what a crappy job his number two was doing that he kicked him out the city.

For Antony, this was a real double whammy. See, Caesar hadn’t returned from Egypt alone, but with Antony’s old flame Cleopatra in tow. Only Cleopatra was now a client of Caesar – which meant he’d put her on the throne, and she in turn had been impregnated with his son, Caesarion.

When Antony was exiled to Gaul, he wasn’t just stewing over his broken relationship with Caesar, but also Caesar shacking up with his crush.

Sadly for Antony, this double whammy was about to become a triple hit. In 45 BC, Caesar was forced to go fight the Sons of Pompey in Hispania – i.e. modern Spain. But with Antony in disgrace, he needed a replacement by his side. The man he chose? His 18-year-old great-nephew Octavian; the future emperor Augustus.

It was the beginning of a rivalry between Antony and Octavian that would shake the known world.

Death of an (almost) King

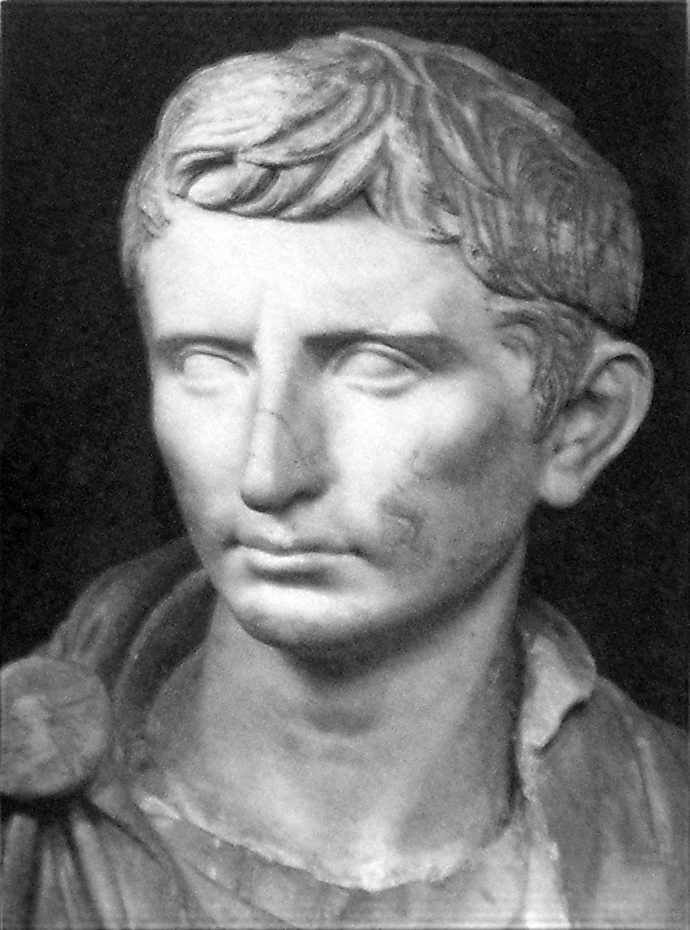

So, now might be a good time to talk about Octavian. Born in 63 BC, Octavian was twenty years younger than Mark Antony. Like Antony, he had a family connection with Caesar, who was his grandma’s brother.

But Octavian never saw his famous great-uncle, and may not have made much an impression if he had. Octavian was weak and sickly. In fact, when 45 BC rolled around and Caesar asked Octavian to accompany him to Hispania, Octavian was too ill to go.

But what Octavian lacked in muscles of steel, he made up for in his iron will.

The boy was ambitious, and he knew the path to greatness lay through Caesar. As soon as he was capable of moving, he dragged himself to Hispania to witness the end of the war. Pleased his weak nephew had put himself in such danger, Caesar honored Octavian by letting him ride home alongside him.

It was likely during this journey that the fate of Rome was transformed. But we’ll get to that soon. While all this was happening, Antony was still sitting in miserable exile in Gaul.

And there he might have stayed, had Caesar not swung by to see him on his way back to Rome. It was now almost two years since Caesar had knocked up Antony’s lady and kicked him out, so we like to imagine the greetings were super awkward.

But the two men soon overcame their differences.

Antony was a dyed-in-the-wool Caesar loyalist. And old Julius never could say no to a sycophant. He asked Antony to return with him to the Eternal City. And so it was that, in 45 BC, three of the most important men in history traveled together across Gaul.

But all was not well back in Rome.

After the Rubicon thing, Caesar’s enemies were pretty sure he meant to make himself into a king.

Not that Antony helped matters.

In February, 44 BC, Caesar was presiding over a religious ceremony when Antony suddenly clambered up towards him, pulled out a laurel crown, and tried to declare his boss King of Rome. Caesar waved him off, but the damage had already been done. Here was the dictator’s number two, literally trying to crown him king. If you were a Republican-minded senator back then, what would you have done?

On March 15, 44 BC – the Ides of March – the Senate summoned Caesar.

As Caesar was on his way, Antony received a warning that something was about to happen, and rushed to tell his boss. He actually caught sight of him, walking into the Senate, and tried to shout a warning. But the crowds were too heavy, and his voice was lost on the bustle of Rome’s streets.

Antony would never see his mentor alive again.

Julius Caesar was stabbed to death that day, killed by his own Senate. In the aftermath of the assassination, Antony fled Rome, convinced he was next. But Antony was wrong. The plotters had never thought to kill off Caesar’s loyalists. Antony, Octavian… all were left alive.

When Antony finally clicked that no-one was coming for him, he returned to Rome and reassumed his position of Consul. The first thing he did was open Caesar’s will, curious to see what this man he’d served so loyally had left him.

What Caesar had left him was a punch in the gut.

Caesar’s will left nothing to Antony. But it did leave a huge fortune to Octavian, as well as posthumously adopting the boy, turning him into Caesar’s only Roman son. Suddenly, Antony was no longer the biggest man left standing, no longer the obvious heir to the dictator.

There was now a powerful rival for Antony in Rome. And there was only one way this rivalry could ever end.

The Triumvirate Reborn

If the conspirators ever had considered killing Antony, they likely spent Caesar’s funeral wishing they’d done it. During the procession, Antony held Caesar’s bloodstained toga high, and gave a thunderous speech denouncing those who’d murdered him.

The crowd was whipped into such a frenzy that the conspirators were forced to flee. But Antony didn’t really want vengeance. What he wanted was to take over Caesar’s old job. So after getting the crowds riled up, he began meeting with the Senate, trying to negotiate a peaceful solution.

Unfortunately, he hadn’t counted on Octavian.

When Octavian first heard of Caesar’s assassination from Antony, he’d also heard that the dictator had willed all his possessions to the Roman people. When he found out Caesar actually left everything to him, he’d figured out what Antony’s game was.

From that point on, Octavian did everything in his power to hobble the older man.

His opening salvo was to reveal to the riled-up mobs that Antony was doing a deal with the Senate. Octavian whipped them up into such a fury that Antony was forced to beat a retreat from peace and declare himself on the path of vengeance.

The upshot was that, in January, 43 BC, Antony rode out at the head of an army to Cisalpine Gaul, where the assassin Decimus Brutus was lying low. And no, that’s not the famous Brutus, just another assassin of Caesar also called Brutus. Go figure.

Anyway, long story short: the Senate got annoyed at Antony’s unilateral action, and sent Octavian to stop him. Instead, the two rivals joined forces, destroyed Brutus’s army, and drove him into the wilds. A few days later, a local tribe sent a box to Antony. Inside it lay Brutus’s head.

Shortly thereafter, Antony and Octavian met on a small island under the eye of the mutually-trusted Lepidus. The fight with B-list Brutus had shown both men how powerful they could be together. Although they despised one another, neither was stupid. They knew that, alone, they might annihilate themselves…

But, together, they could take the whole of Rome.

And so the Second Triumvirate was born.

Forged between Antony, Octavian, and their friend Lepidus, the Second Triumvirate would rule Rome for ten years. They were effectively invincible. When they returned to Rome, the Senate basically just handed them the keys to the city.

When the Triumvirs announced the property of 2,000 Republicans was now forfeit to fund the coming war with the real Brutus and his co-assassin Cassius, everyone just looked the other way.

But make no mistake.

The Second Triumvirate was not an end in and of itself, but a stepping stone. All three parties wanted to rule Rome solo. All three knew that, at some point, they’d have to kill their rivals.

The only question was when.

In 42 BC, Antony and Octavian finally rode east to confront the assassins, leaving Lepidus in Rome. The first battle came in September, and only resulted in a draw. A brilliant maneuver by Antony captured Cassius’s camp, but an equally brilliant act of stupidity by Octavian led to Antony’s camp simultaneously falling to Cassius.

But none of that actually mattered, because Cassius was watching all this from a hill with poor visibility and failed to see his own victory. So, thinking that it was all over, he ordered a slave to kill him. Which left only Marcus Brutus. He of “et tu, Brute?” fame.

On October 23, the Triumvirs forced a final battle. This time, there would be no draw.

Brutus’s army was crushed. In the aftermath, the assassin climbed a nearby hill, pulled his sword, and drove it into his own abdomen.

Brutus was dead. The war was over. To celebrate, Antony and Octavian divided the empire between themselves: the west – minus Gaul – going to Octavian, while the east went to Antony.

As Octavian headed back for Rome, Antony was left wondering what to do. He was now one of the two most influential men on Earth, lord of all that lay east of the Adriatic. What’s a guy to do given all that power?

Why, what any guy would do of course! Antony went off to impress a girl.

The Triumvir and the Queen

And so here we are. After over half the video, we finally get to the part of Antony’s life everyone remembers. His relationship with Cleopatra. That the two became lovers at all is purely down to luck. While Antony might have been smitten by the Egyptian queen years ago, Cleopatra tended not to have relationships out of love, but out of necessity.

Come 41 BC, though, what Cleopatra needed was a guarantee from Rome that it would continue to prop up her throne. And what better way to secure that guarantee than by seducing a Triumvir? Although Antony was the one who arranged their meeting, it was Cleopatra who controlled it.

She arrived at Tarsus on a boat with silver oars, dressed as Aphrodite, while girls waited on her every whim and Greek music played. For Anthony, who’d become obsessed with both Cleopatra and Hellenistic culture in his youth, this must’ve been like watching all his late-night fantasies come true.

In fact, Antony was so smitten that he accompanied the queen back to Alexandria that winter, where the two formalized their alliance. But while “Clantony” or “Antopatra” may have started as an alliance of convenience, it soon grew into something bigger.

That winter in Alexandria, the Queen and the Triumvir were inseparable.

They started a group called “The society of inimitable livers,” where they drank as much fine wine and eat as much fancy food as they could stomach. They went out in the streets at night together, wearing disguises so no-one would recognize them. By day they hunted.

And slowly, inevitably, they began to fall in love.

Not that Antony had taken his eyes off the prize. That same winter, Antony’s family in Rome tried to foment rebellion against Octavian – likely on Antony’s orders. But Octavian survived the rebellion and not only exacted ruthless revenge, but took Antony’s province of Gaul for himself.

This very nearly led to yet another civil war, but neither Antony nor Octavian was strong enough yet. But make no mistake. The blood between these two was worse than it had ever been.

When the Second Triumvirate’s term was renewed in 37 BC, part of the deal was that Antony would trade 120 ships for four of Octavian’s legions. Antony sent the ships off to Rome… only to realize too late that there would be no legions coming. Octavian had tricked him.

Yet Antony still couldn’t just march on Rome and destroy his young rival, just as Octavian couldn’t barge into Alexandria. What Antony needed was a PR triumph. Something that would turn the whole of the Rome into his fanboys.

Something like a glorious victory in war.

In 36 BC, Antony invaded Parthia.

The choice was wonderfully symbolic. In 53 BC, Parthia had humiliated Rome. Julius Caesar had actually been preparing to attack right before his assassination. If Antony could finish what Caesar started, there’d be no doubt about who was Julius’s real heir.

Sadly, that was a big “if”.

For the Romans, invading Parthia was kind of like modern European dictators invading Russia – it rarely worked out.

Antony marched in, expecting easy victory…

…and instead watched as brutal weather killed over a quarter of his soldiers. He was forced to retreat without fighting a single battle. The bodged invasion was so humiliating that Antony seriously considered suicide. In the end, though, he simply slunk back to Alexandria, to take comfort in Cleopatra’s arms.

There would always be another chance. He just had to lick his wounds and try again later. But Antony was wrong. There wouldn’t be another chance.

His fate had already been sealed.

Octavian Rises

If the Invasion of Parthia was a PR blunder, then what Antony did next was like live-streaming a video of himself wearing swastikas while kicking puppies. Back in Alexandria, Antony began to dress more and more in eastern fashion. He began acting not like a staid, boring Roman, but like a hedonistic Greek.

And this infuriated the staid and boring Romans! Going native just wasn’t done.

On top of that, Antony started calling Cleopatra “queen of queens,” a warning sign that the Romans might have to put up with a non-Roman empress if Antony defeated Octavian.

But Antony’s biggest mistake was probably what he did with Caesarion.

Remember Caesarion? He was the lovechild of Julius Caesar and Cleopatra who got, like, a one second introduction toward the start of this incredibly-crammed video. Well, Antony declared that not only was Caesarion “king of kings,” but that he was also the true heir to Caesar.

For Octavian, this was like a gigantic warning sign flashing “YOU WILL NEED TO KILL THIS DUDE ASAP.”

So Octavian prepared his final push. First, he removed Lepidus from the Triumvirate, consolidating his power in the western empire. Second, he started a fierce propaganda war, painting Antony as a weak general under the spell of a wicked queen.

From Alexandria, Antony tried to fire back. He started a rumor that Caesar only adopted Octavian because the boy had seduced the dictator.

But Octavian was just better at this kind of scheming. When the Second Triumvirate’s term expired, he announced he no longer wanted the title. When Antony hesitated about dissolving the Triumvirate, Octavian was able to paint him as a power-hungry tyrant.

Oh, the irony. Things finally crumbled in 32 BC. Octavian stormed into the sacred temple holding Antony’s will and removed it, breaking every taboo in Roman society. But when he read it to the masses, and it turned out Antony had done even worse.

In his will, Antony had left the entire eastern part of the empire to Cleopatra and her sons. This was no longer just going native. This was treason. In a bruising session, the Senate declared war on Antony, granting Octavian the power to fight his rival.

Down in Alexandria, Antony realized the time had come.

Taking 400 ships, he appointed Cleopatra his co-general, then sailed out in an awe-inspiring show of force.

Sadly, a show was all it was.

For whatever reason, Antony was wary of attacking Rome directly. So he hung back, wintering his ships to the south, in a little bay with only a narrow entrance. In effect, this bay became his own noose.

In spring, 31 BC, Octavian’s ships managed to blockade Antony inside the bay. At the same time, a huge overland army cut off their escape. For the next half year, Antony and his men were trapped in a state of siege, with too little water, too little food, and way too much disease.

Finally, realizing his entire army was on the verge of deserting, Antony forced a battle on September 2. The Battle of Actium is today a byword for humiliating defeat. Octavian’s ships pummeled Antony’s weakened navy, reducing it to so much driftwood.

It was only a chance break in Octavian’s line that allowed Antony and Cleopatra to personally escape in a fast boat, high-tailing it back to Egypt. But there would be no escape now. No second chances.

Octavian was coming for them.

And he wouldn’t rest until Antony was dead.

“We are for the Dark”

The end of Mark Antony’s life is one of the saddest examples of refusing to accept reality that you’ll ever see. At first, Antony and Cleopatra seem to have decided they could reason with Octavian, and spent all winter sending him envoys.

When Octavian laughed them off, they began preparing a clearly doomed defense of Alexandria.

Yet neither seems to have realized the writing was on the wall. As they waited for winter to pass, Antony and Cleopatra repeatedly got drunk and talked about what they would do once they’d finally defeated Octavian.

It was like hearing two pigs discuss what they’d do once they’d taken over the slaughterhouse: depressing and amusing in equal measure.

At long last, in the final days of July, 30 BC, Octavian’s fleet was spotted on the horizon. On August 1, Antony sent out the remnants of his navy to meet them while he amassed an army on land.

His plan was to give Octavian’s ships hell, and then die gloriously in battle, a soldier to the end. Alas, fate had other plans. As soon as they approached Octavian’s ships, Antony’s navy raised the white flag of surrender.

On land, his army saw what was happening, thought the Ancient equivalent of “to Hell with this,” dropped their weapons and mass deserted. The only one left was Mark Antony, standing impotently on the hot Alexandrian shore, watching death approach.

Humiliated, the great general tried to return to Cleopatra’s palace and see her one last time.

But Cleopatra had sensed which way the winds were blowing and had gone into hiding in an unfinished mausoleum. She made one of her aides tell Antony that she’d already committed suicide. Faced with the loss of his empire, of his queen, and of certain death, Antony did the only thing he could.

He drew his dagger and stabbed himself in the stomach. Then he slid down onto the floor, bleeding and in agony.

But the story isn’t quite over yet.

Stomach wounds can take a long time to kill you. When Cleopatra heard what Antony had done, she changed her mind and sent for him. The dying man was dragged to her mausoleum, leaving a trail of blood in his wake. There, he was propped up, facing his queen for the final time.

At the sight of her lover, Cleopatra burst into tears. Antony briefly tried to comfort her, but thought better of it. With his last ounce of strength, he demanded wine be brought. He took the cup, toasted his queen, and then drank for the final time.

We don’t know Mark Antony’s real last words, but Shakespeare had him declare:

“The miserable change now at my end

Lament nor sorrow at; but please your thoughts

In feeding them with those my former fortunes

Wherein I lived, the greatest prince o’ the world,

The noblest; and do now not basely die,

Not cowardly put off my helmet to

My countryman,–a Roman by a Roman

Valiantly vanquish’d. Now my spirit is going;

I can no more.”

Mark Antony died on August 1, 30 BC, just hours before Octavian captured Alexandria. In the aftermath, the 33-year old had Caesarion killed, before annexing Egypt into his empire. Although he allowed Cleopatra to live, he let her know it would only be as a miserable wretch, without money or power, rotting in some obscure Roman province.

Cleopatra committed suicide on August 30. She was the last pharaoh of Egypt.

Just three years later, in 27 BC, Octavian assumed the name Augustus, becoming the first Roman emperor. Already, most had forgotten Mark Antony, forgotten the man who came so close to ruling the empire.

But not everyone.

In the 2,000-plus years since his death, Mark Antony has become a household name, one of the few ancients almost everyone remembers. Partly, this is due to his proximity to Caesar. Partly, it’s to do with Shakespeare. Partly it’s probably also to do with Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor.

But there’s more to this than simply luck.

Mark Antony’s story is a fascinating mix of so many things. It’s an adventure story. A story about how power corrupts. A love story for the ages. A branching point for a million alternate history tales. In short, it’s a myth. A myth where Godlike kings and emperors battle and rule and fall in love, doing everything on a scale far beyond normal human life.

And yet, it really happened.

The life of Mark Antony may have been a failure, but it’s also one that speaks to us; as poetic as any epic, as powerful as any legend. Here, in the fires of love and war, the fate of the known world was decided, changing our planet’s history.

He may have never been emperor. He may have been outplayed by Octavian.

But Mark Antony was a historical colossus. A guy who did more and loved more in his lifetime than most of us could ever dream of. In retelling his tale, we can experience just a shadow of those great feelings too.

Sources:

Utterly excellent, multi-part podcast retelling of Antony and Octavian’s rivalry (plus background). This is the first episode: https://thehistoryofrome.typepad.com/the_history_of_rome/2009/03/46-sic-semper-tyrannis-the-history-of-rome.html

Good, detailed, readable bio: https://www.ancient.eu/Mark_Antony/

ThoughtCo: https://www.thoughtco.com/mark-antony-4589823

Some good details on Antony and Cleopatra: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/magazine/2015/10-11/antony-and-cleopatra/

Britannica’s bio: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mark-Antony-Roman-triumvir

History’s take: https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-history/mark-antony

Biography’s take: https://www.biography.com/political-figure/mark-antony

The Battle of Actium: https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/the-battle-of-actium

Antony’s death scene in Shakespeare: http://www.shakespeare-online.com/plays/antony_4_15.html