There’s a famous saying that women have to do twice as much work as men to receive half the credit. That’s likely never been truer than in the life of Maria Theresa. The eldest daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI, Maria Theresa was born at a time when the idea of a woman running Austria was as absurd as giving the poor the vote. When she took over from her father aged 23, she was immediately forced to fight for her empire’s very survival, as Europe’s kings sought to tear her inheritance away from her.

Yet fight Maria Theresa did. Not only that, she won. When the dust finally settled, it was on a strengthened Austria that would soon transform the entire continent.

Over the next three decades of her rule, Maria Theresa enacted reforms that changed the world; fought off attacks from powerful enemies; and gave birth to a litany of famous children, including Marie Antoinette. Through cunning, tactical-marriages, and sheer obstinacy, she forced a once-hostile Europe to bend to her will. Today, we’re investigating the story of one of Europe’s most-influential empresses.

Kaiserin Maria Theresia

A Man’s World

The moment she was born in Vienna, on May 13, 1717, it’s likely Maria Theresa set a world record in disappointing her parents. That was because she was born a “she,” at a time when Austria desperately needed a royal baby boy.

Maria Theresa’s father was Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor and a member of the powerful Habsburg dynasty.

Unfortunately, the Habsburgs’ golden rule was that only males could inherit their Crown Lands – a swathe of territory including modern Austria, Hungary, and Czech Republic, plus chunks of everything from Romania, to Croatia, to Belgium.

This was fine when emperors were siring baby boys and had a plethora of brothers waiting in the wings, but Charles had neither. As far as the continent was concerned, unless Charles had a son, the House of Habsburg would go extinct along with him.

But Charles thought he’d found a loophole.

In 1713, five years before Maria Theresa failed to be born with a Y chromosome, the Emperor issued something known as the Pragmatic Sanction.

Essentially a piece of legislation that said “you know what? We’re cool with girls now,” the Sanction tried to put into law the idea of female inheritance. At first, it was purely hypothetical. But, after Maria Theresa was born, Charles began a PR drive to make everyone accept it.

Since the Habsburg lands weren’t unified, that meant spending years traveling to various Austrian duchies and kingdoms like Bohemia, and trying to convince stuffy 18th Century dudes that girls were more than just vectors for spreading cooties.

Unfortunately, deep down, it seems even Charles himself didn’t believe this.

Although the Sanction meant she might soon be empress, Maria Theresa’s childhood was spent learning zero necessary skills. To give just one example, it was customary for male heirs to learn the empire’s fiendishly complex languages, like Hungarian and Czech.

But Maria Theresa was instead given courses in languages designed to make her more marriageable, like French and Latin.

Nor was she taught anything about diplomacy, warfare, politics, or even the basic practicalities of running an empire. It’s almost like Charles was just fundamentally incapable of imagining a female ruler, no matter what his Sanction might say.

He even tried to marry his daughter off to a “powerful prince”, who’d at least be able to defend the empire’s integrity.

But that plan fell by the wayside when his now-teenage daughter went and fell for Franz Stephan.

The heir to the territory of Lorraine, Franz Stephan was certainly important. But he was also way more a dreamer than he was a mighty warrior. Still, to his credit, Charles allowed his daughter to marry for love rather than dynastic reasons, a laughably rare occurrence at the time.

Rarer still, that love actually survived.

Despite Franz being the sort of guy who couldn’t go five minutes without removing his pants and making for the nearest countess, Maria Theresa doted on him.

Over the decades, their union would produce 16 children, including two Holy Roman Emperors and Marie Antoinette. Those children would be prodigious baby-makers, too. By the time she eventually died, Maria Theresa would be a grandmother 56 times over.

Sadly, none of her first children would have that elusive Y chromosome.

On October 20, 1740, Charles VI died. Aged just 23, Maria Theresa ascended to the Austrian throne.

At first, it looked like the Pragmatic Sanction had worked. She made her husband co-regent, and the various duchies and kingdoms of the Habsburg Lands recognized her.

But while the Sanction may have smoothed the transition internally, it certainly hadn’t worked where the rest of Europe was concerned. To the continent’s male rulers, Maria Theresa was an illegitimate empress sitting atop a whole lot of prime real estate.

There was only one way this could ever pan out.

It was time for Europe to go to war.

The Fight for Survival

In retrospect, one of the most-impressive things about Charles VI is just how incapable he was at planning. We’ve already seen how he didn’t prepare Maria Theresa for ruling Austria. Well, he also failed to prepare Austria for Europe ignoring his Sanction.

There was no military buildup prior to his death. No money or weapons set aside for defending the Crown Lands.

As his daughter later commented, she became head of an empire with no money, no army, no experience, and no advisors.

Given all that, perhaps the only surprising thing is that the war took two whole months to kick off.

The ball started rolling the moment Maria Theresa ascended to the throne.

See, the emperor before Charles, Joseph I, had likewise failed to produce any male heirs.

When he died in 1711, the throne had passed to his younger brother, our friend Charles.

But Joseph had had daughters. Some of whom had married powerful men.

Now that Charles’s daughter had become ruler, those powerful men were wondering why their wives – Joseph I’s daughters – didn’t get to inherit Austria. The biggest challenges came from the Electors of Saxony and Bavaria, who formed an alliance with Austria’s old rival France and started making claims on her territory.

But the major threat to Maria Theresa’s reign would come from another direction entirely.

Over in Prussia, Frederick the Great was newly on the throne, and determined to live up to his future-nickname.

On December 16, 1740, his army marched into the filthy rich Habsburg province of Silesia and annexed it.

It was the starting gun on the War of Austrian Succession.

It would very nearly result in the destruction of Maria Theresa’s empire. The early days of the war were marked by Maria Theresa scrambling to grab even a shred of legitimacy. As Prussia wiped the floor with Austria’s troops, the young woman floundered for allies.

Her biggest win came in June of 1741, when she visited the Hungarian Diet, her newborn baby son clutched in her arms, and gave a rousing address asking for the noblemen’s support.

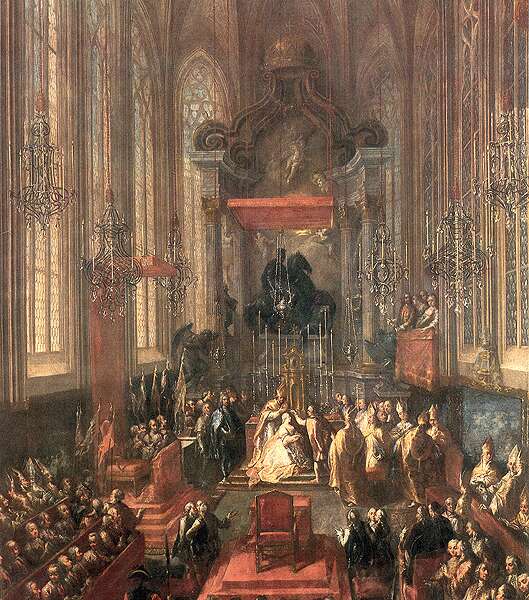

Shortly after, she was officially crowned Queen of Hungary.

But this was just a small island amid a sea of catastrophe.

That July, Charles Albert of Bavaria invaded Bohemia, and had himself crowned king in Prague. At the same time, French troops marched into Upper Austria, bringing the fight onto Habsburg turf. As her inheritance evaporated before her eyes, Maria Theresa tried to hold onto the title of Holy Roman Emperor.

Although not hereditary, the title had been in her family for centuries.

While there was no chance of a female Holy Roman Emperor, Maria Theresa hoped to at least convince the Electors to appoint her husband. Instead, she was forced to watch in horror as Charles Albert managed to get the Empire’s Electors onto his side.

On February 12, 1742, he was crowned Holy Roman Emperor Charles VII – the first non-Habsburg to hold the title in almost 300 years.

It was a crushing PR blow for the young, inexperienced Maria Theresa. To Europe at large, it looked like final proof that the game was over for this upstart, female pretender.

You know how they say that the night is always darkest before the dawn?

Well, the sun was about to come up on Maria Theresa’s fortunes.

And, when it did, she was going to show all these overconfident men what she was really made of.

Turning the Tide

The first victories Maria Theresa won weren’t on the battlefield, but in the realm of diplomacy. In 1741, before Charles Albert became Holy Roman Emperor, she persuaded the British to join her side. To be fair, this wasn’t that difficult. Even today, British logic operates on a kind of “the enemy of France is my friend” track, and Austria was very much France’s enemy.

But it was still a significant win.

Of all the powers attacking Maria Theresa’s empire, France was by far the scariest. With Paris suddenly tied up fighting London, it gave Austria’s army a chance to act. In the spring of 1742, while Charles Albert was still sat in Frankfurt acting all smug, Austria invaded and occupied his home state of Bavaria.

Then, before the new Emperor knew what had hit him, Maria Theresa swallowed her pride and did something very painful.

She gave Frederick the Great exactly what he wanted.

In return for giving up Silesia, Maria Theresa ensured her other scary enemy – Prussia – was also out the war. And that left only weaklings like Bavaria to deal with. By May of 1743, Austria’s troops had retaken Bohemia, leaving Charles Albert an exile without a kingdom.

That same month, Maria Theresa was officially crowned Queen of Bohemia in Prague – a slightly gross experience as the corpses of enemy troops were still lying in the streets. Not long after, the British smashed the French at the Battle of Dettingen. That September, Maria Theresa convinced Savoy to join the war.

Faced with mounting losses and new enemies to fight, the French were all like “you know what? Screw this,” and retreated back behind their borders, leaving poor Charles Albert isolated.

Although the war would drag on for several more years, it was effectively over.

In January, 1745, Charles Albert died while still in exile. Seeing how hopeless the situation was, his son and successor cut a deal. In return for Austria withdrawing from Bavaria, he’d give up all claims on Maria Theresa’s territory.

That autumn, the Holy Roman Empire elected Franz Stephan its new ruler, under the name Francis I.

Although it was her husband actually on the throne, Maria Theresa never left any doubt about who was really calling the shots.

As the war wound down, the only bum note was the permanent loss of Silesia to Frederick the Great.

Austria gamely tried to fight and reclaim it, but given he’s known as “Frederick the Great” and not “Frederick the Crappy”, you can probably guess how that went.

The War of Austrian Succession finally ended in October of 1748.

Against all the odds, Maria Theresa had done it. While Silesia was gone, the rest of her territory was intact, the title of Holy Roman Emperor was back in her family, and Europe was no longer in any doubt about a woman ruling Austria.

If she’d been just a little less skilled at diplomacy, a little less quick on her feet, Maria Theresa could’ve watched her entire legacy vanish before her eyes.

Instead, her empire would now survive – in one form or another – all the way until WWI.

But Europe’s young empress wasn’t merely content with holding her territory.

The war had exposed how weak her empire really was. How decentralized and vulnerable.

If Maria Theresa wanted her lands to survive, she was going to have to give them a serious overhaul.

Little could she have known just how far-reaching the impact of these reforms would be.

Reform

The biggest contradiction of Maria Theresa’s life is that her reforms would liberalize the whole of Europe, all while she herself was a staunchly Catholic conservative. On paper, Maria Theresa had no more inclination toward improving her subjects’ lives than Napoleon had toward not conquering everything in sight.

But she was a practical person. If a reform would benefit her empire, she would pursue it regardless.

It was this quality that would turn her into one of the greatest rulers in history. The transformations that took place under Maria Theresa can be summed up with three words: centralization, professionalization, and efficiency.

Let’s tackle them in order.

The first thing to know is that the Habsburg Lands were not a unified empire.

Each of the regions had its own feudal diet ruling at the local level.

That meant the empire had no control over local administration, relying on a handful of lords and bishops to do everything from collect taxes to write laws.

Maria Theresa swept all this archaic nonsense away.

Under her watch, the empire’s various parts were integrated into a coherent whole.

New civil servants were trained to take over from the diets. The nobility and the Church lost both their powers and their tax-exempt status. With this political centralization came a drive to do the same for the economy.

Internal tariffs that had existed for centuries were abolished, the entire empire absorbed into a single market.

A census was introduced, and researchers sent to gather data on the empire’s lands, allowing for more-rational policies to be formulated. To do all this census-taking and administering, Maria Theresa stopped relying on unqualified members of the nobility, and started promoting the professional middle class.

Likewise, the buffoonish aristocrats in the military were ejected, and actual, competent officers brought in.

For the first time, Austria was able to maintain a standing army, trained in the latest warfare techniques.

And, just as centralization naturally led to professionalization; so creating this new professional class inevitably led to overhauling education. One of the biggest triggers came in 1749, when the judiciary was separated from the state.

This created a sudden, desperate need for learned judges, alongside all the new civil servants.

So Maria Theresa threw open the doors to higher education. Approved the then-radical notion that students should be taught from textbooks.

She also took education out the hands of the Church, ensuring subjects were taught by people who knew what they were talking about. But the biggest change was the slow introduction of compulsory schooling – the first step towards universal primary education.

Of course, for Maria Theresa, the point of all this wasn’t to educate the populace, but to quickly train the educated class her other reforms called for. That’s what we meant by “efficiency”. But her efficiency still came with a giant – if accidental – dose of enlightenment ideals.

Take her economic reform of physiocracy.

At its most-basic, physiocracy suggested that a higher birth rate would produce more workers, which would make the empire richer. Realizing that ill-treated peasants weren’t able to sustain packs of children, Maria Theresa eliminated the rights of feudal overlords to dominate their peasants’ lives.

She also overhauled healthcare.

Seeing the death rate for women during childbirth, Maria Theresa founded the first maternity hospitals and obstetrics departments, while also forcing midwives to earn qualifications instead of just improvising. Oh, and she also championed inoculation against Smallpox, putting her ahead of anti-vaxxers before there were even any vaccines to be “anti” about.

In short, Maria Theresa completely overhauled her empire, dragging it into the modern world.

So successful were many of her reforms that they’d be taken up by other European leaders, adding to the era of enlightened absolutism now sweeping the continent. But while she’s famous today as a reformer, that doesn’t mean every reform Maria Theresa undertook was a good one.

It’s time we took a hard look at the darker side of her reign.

Intolerance and Violence

As a hardcore Catholic, Maria Theresa naturally disliked anything that smacked of hearsay.

Unfortunately, that included a good number of her own subjects.

The first target of her prejudices were Protestants.

Even though the Counter-Reformation had been dead and buried for a century, Maria Theresa still felt Protestantism was fundamentally illegitimate. When it came time to resettle depopulated lands in what is today Romania, it wasn’t good Catholics she shipped out there to eke out a living, but Protestants who’d been expelled from the cities.

But at least this was still in-keeping with her practical side. She had a region that needed settling, so she sent her unwanted Protestants there.

There same couldn’t be said of her persecution of the Jews.

Despite the Jewish community in Prague dating back centuries, Maria Theresa kicked off her reign by expelling 20,000 of them.

Jewish families were given almost no warning before their community was dissolved, ending generations of tradition.

And don’t go thinking “oh well, this is just how things rolled in 18th Century Europe”. Maria Theresa’s own son, Joseph II, would pass a law right after she died, undoing most of her anti-Jewish legislation. The other minority Maria Theresa had no truck with was anyone who didn’t believe in God-fearing, Catholic marriage.

Unsurprisingly, this included gay people. But it also included people who committed adultery, and even Catholics who dared to have sex with Protestants.

To enforce this, she introduced a chastity court that could order anything from whipping, to deportation, to execution.

That’s if they survived the torture.

Yep, torture. While a general move to outlaw torture was gathering steam across Europe, Maria Theresa resisted it, believing the practice was necessary and useful.

Finally, there was her toxic relationship with her son.

In 1765, Franz Stephan died, leaving Maria Theresa heartbroken.

The very next day, she elevated her eldest son, Joseph II, to her co-regent, successfully getting him likewise installed as Holy Roman Emperor.

But as long as she was still alive, there was no doubt who was really in charge.

This was unfortunate, because Joseph had inherited his mother’s reforming zeal, boosted even further by his enlightenment beliefs. This meant toleration for other religions, extended rights for the very poorest, and open admiration for mega-reformer Frederick the Great – sadly, all anathema to Maria Theresa’s ears.

The weird result was that Maria Theresa spent the first half of her reign transforming her empire… and the second half fighting tooth and nail to stop her son from taking those reforms to their logical conclusions.

But we shouldn’t write her reign off as a mere precursor to Joseph’s.

Although her overhauls were baby steps, they were genuinely groundbreaking for the time, taking place years before other reformers like Catherine the Great arrived on the scene; and decades before Napoleon. If it hadn’t been for having to share a continent with Frederick the Great, it’s likely Maria Theresa would’ve been by far the most significant monarch of her time.

But there were other ways she was significant for Europe, too.

It’s time we took a look at Maria Theresa’s other great skill: marriage diplomacy.

All in the Family

If practicality was what had driven Maria Theresa’s reforms, it was certainly what governed her attitude to family. Her kids weren’t living children, but commodities to invest in, or else marry off to powerful rulers.

And no-one did marriage diplomacy quite like Maria Theresa.

Starting in the 1750s, she decided to neutralize the French threat by marrying as many of her daughters to as many Bourbon princes as humanly possible. Famously, this included Marie Antoinette – known in Austria as Maria Antonia – sent to France to marry Louis XVI. But it also included nearly all her other girls, nearly all also called Maria.

Maria Karolina, for example, was dumped onto King Ferdinand of Naples and Sicily, a ruler once described as both “uncouth and mentally retarded.”

Maria Amalie begged not to be forced to marry the Duke of Parma, only to find herself unhappily walking down the aisle with him.

Even where marriage was concerned, there was a ruthlessness to Maria Theresa.

When Maria Elisabeth’s good looks were ruined by smallpox, she was entirely removed from her mother’s marriage schemes, and left in isolation to go half-mad. In fact, the only daughter Maria Theresa extended the same courtesy her father had to her was Maria Christina, who was allowed to marry for love and do pretty much as she pleased.

The rest of this gigantic brood of Marias spent their entire lives controlled and dominated by their powerful mother. This was a key part of marriage diplomacy. Her daughters installed in helpful locations, Maria Theresa would write to them, telling them exactly what to do and how to behave.

It drove Marie Antoinette bonkers, causing her to confide in her Versailles friends that her mother was a dreadful old cow.

She may have had a point.

Maria Theresa seems to have regarded all her daughters as inherently stupid and in need of berating, like the time she bluntly told one of them:

“The less you speak the better (…) I know the manner in which you chatter away and must tell you as a friend that it is very tedious and larded with all sorts of platitudes.”

Ouch.

But the children were more than just cannon-fodder for marriages. They were PR tools, too. Maria Theresa knew from experience that being a female ruler was often a handicap. But she knew it could also work to her advantage.

When invariably male diplomats arrived from foreign lands, she’d greet them accompanied by all her children; projecting “womanly” virtues like motherliness and caring that convinced these stuffy dudes she wasn’t a threat.

It was cold, it was calculating. It was unfair to her kids.

But it also worked.

Thanks to this practical attitude toward her offspring, Maria Theresa was able to turn the French into her allies. To make enemy states into grudging friends.

Well, at least until the French rose up and chopped her daughter’s head off. But that’s a tale for another video. All in all then, Maria Theresa’s family diplomacy was successful at quietening Europe, at least for a time.

Sadly, time was something Maria Theresa no longer had.

A Painful End

The slow march toward the end of Maria Theresa’s life began on August 18, 1765. That day, Franz Stephan died suddenly, ripping away the one person she truly adored. Although her son, Joseph II, would be elevated to co-regent, the effect Franz Stephan’s death had on her would be catastrophic.

For the rest of her life, Maria Theresa wore clothes of mourning.

She stopped attending public events, cloistered herself away, and slipped into something that looks suspiciously like depression. The most-pathetic remnant of this time is probably a piece of paper found after she’d died, in which she’d worked out exactly how long their marriage had lasted:

“29 years, 6 months, 6 days; that makes 29 years, 335 months, 1540 weeks, 10,781 days, 258,744 hours.”

It was around this time that she also became increasingly conservative.

We’ve already mentioned how Maria Theresa changed from a reformer into someone fighting her son’s edicts at every turn. Well, this about-face also applied to foreign policy. Ever since the War of Austrian Succession, Maria Theresa had promoted herself as the “empress of peace,” someone who wanted to stop war coming to Europe.

But in 1772, she took part – along with Prussia and Russia – in the First Partition of Poland, annexing Galicia and threatening the entire balance of Europe.

As her old enemy Frederick the Great sneered of her reluctant annexation:

“She wept, but she took nonetheless”.

As the years began to mount up, Maria Theresa started to fail physically.

From a lithe, athletic woman, she became badly overweight. Her son – and future Holy Roman Emperor – Leopold II wrote despairingly:

“Owing her age and her corpulence she is beginning to have great difficulty in walking… Her memory has deteriorated considerably… (She) mistrusts herself and everybody else. She never enjoys anything and is constantly alone and melancholic.”

At last, her ailing body gave out completely.

Maria Theresa died of pneumonia on November 29, 1780, aged 63.

She was buried in Vienna alongside her beloved Franz Stephan, the pair finally reunited after a decade and a half apart.

At the moment of her passing, it wasn’t clear how Maria Theresa would be remembered. Her reforms that had once seemed so revolutionary now looked like mere tinkering compared to those of Joseph II. Not a decade later, even Joseph’s reforms pale in comparison with the changes the French Revolution unleashed.

Against all that came after, what were the basic, practical changes Maria Theresa had made?

But this wasn’t the story’s end.

As the years marched on, it soon became clear that Maria Theresa had laid the foundations for Austria’s golden age. As the empire lived longer and longer – all the way into the 20th Century – it started to look more and more like Maria Theresa’s practical spirit had been perfect for her time and place.

Today of course, with Austria’s empire over a century dead, we’re far-more likely to remember other aspects of Maria Theresa’s life.

Here was a powerful woman who didn’t just manage to rule at a time when ovaries could’ve disqualified her from the top spot, but did so with a force and a passion that made her one of the most-influential monarchs in Europe.

At her height, she bent both Austria and Europe to her will, and did so in a way that benefited millions.

She may have been religiously intolerant. She may have lived long enough to become an obstacle to reform, rather than its driver.

But Maria Theresa was a ruler who saw off all her rivals to reign for 40 long years.

In doing so, she ensured not just Austria’s survival… but her place among Europe’s greatest emperors.

Sources:

Danubia by Simon Winder: https://www.amazon.com/Danubia-Personal-History-Habsburg-Europe/dp/0330522795

Biography, overview: https://www.biography.com/activist/maria-theresa

Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Maria-Theresa

Extremely detailed biography from Habsberger.net: https://www.habsburger.net/en/chapter/maria-theresa-heiress

Deutsche Well, What made Maria Theresa one of a kind? https://www.dw.com/en/what-made-austrias-maria-theresa-a-one-of-a-kind-ruler/a-37935974

Silesian Wars Overview: https://www.britannica.com/event/Silesian-Wars

War of the Austrian Succession: https://www.britannica.com/event/War-of-the-Austrian-Succession

Health reforms: https://english.radio.cz/maria-theresa-pragmatic-health-reformer-8193019

Joseph II: https://www.biography.com/political-figure/joseph-ii

Seven Years’ War: https://www.habsburger.net/en/chapter/seven-years-world-war

Czech view: https://english.radio.cz/maria-theresa-empress-who-left-a-mixed-impression-czech-lands-8193664

Frederick the Great: https://www.spectator.com.au/2015/10/frederick-the-great-king-of-prussia-is-a-great-read/

-1-1-e1678303278466-150x103.jpg)