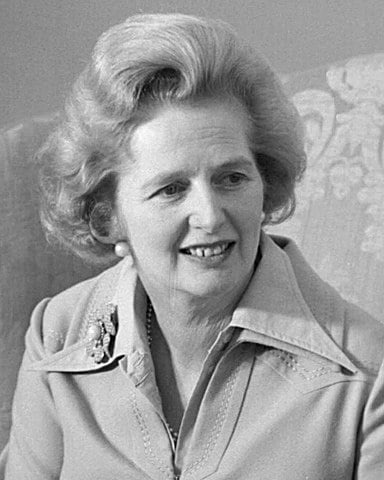

She’s one of the longest-serving Prime Ministers in British history. As head of the Conservative Party, Margaret Thatcher led the UK from May, 1979, right the way through to November of 1990. In that time, she ushered in an era of reform unparalleled in the 20th Century. Under her watch, the postwar settlement was torn up; state assets privatized; the financial market let rip; and the cultural fabric of Britain changed beyond recognition. But the transformations didn’t just stop at home. Alongside her US counterpart, Ronald Reagan, Thatcher helped spread the gospel of economic liberty and individual freedom across the entire planet. When she finally left office, she was widely-recognized as the most-significant British leader since Churchill.

Yet while Churchill is still widely-loved in the UK, Margaret Thatcher’s legacy is hugely divisive. Taking over an ailing Britain, her economic shock therapy devastated entire regions, even as it saved the country as a whole. Both worshipped and reviled at home, this is the story of Britain’s most-controversial leader.

A Man’s World…

When Margaret Hilda Roberts was born on October 13, 1925, there was nothing that suggested she would one day lead her nation. Her father was a grocer, and young Margaret grew up in achingly modest circumstances. The family had no indoor toilet, and warm water was an unknowable luxury.

Yet it wasn’t her petit bourgeois lifestyle alone that made Margaret an unlikely candidate for future PM.

It was the fact that she was a “she”.

Right up until Thatcher became Education Secretary in 1969, there had only ever been four female cabinet ministers in UK history – and not a single Prime Minister. As Thatcher herself would say in a TV interview in 1973, the idea of a woman ever rising beyond the cabinet to become Prime Minister seemed impossible.

Still, despite living in a society that considered casual sexism a legitimate hobby, young Margaret never felt she needed to pursue “ladylike” interests. Her major passion was chemistry, which she studied at Oxford under the Nobel Prize winner Dorothy Hodgkin.

But even as she was winning plaudits for her science work, Thatcher was discovering her other lifelong love: politics.

In 1945, the UK’s first postwar election resulted in a shock win not for Winston Churchill’s Conservatives, but for the leftwing Labour Party of Clement Attlee.

The Labour landslide completely upended Britain. In his six years in power, Attlee created the NHS, the welfare state, and what became known as the “postwar settlement” – an unspoken agreement between the parties that the state needed to interfere in the economy.

Naturally, Thatcher hated this.

One year after Attlee took power, she became President of the Oxford University Conservative Association, from where she railed against the Labour tide transforming Britain.

So good was she at this that it soon convinced her to enter politics proper.

At the 1950 election, Thatcher stood as a Conservative candidate for the seat of Dartford. While some in her party were appalled at the idea of a lady-human running, she still managed to increase their share of the local vote by 50% – an early sign of her electoral prowess.

But it still wasn’t enough to win. Nor did she net enough votes in the 1951 election, despite this being the election that saw Churchill and the Conservatives return to power.

Yet all was not lost.

It was through her campaigning in Dartford that Margaret met Denis Thatcher.

A rich, somewhat dopey guy, Denis would turn out to be the ideal husband.

He was tremendously supportive of Margaret’s ambitions for public office, and so hands-off it was like he was permanently wearing a straight-jacket. Although this did have some odd side-effects – such as when Denis went to the cricket rather than interfere in the birth of their children – he was the solid, supportive rock Margaret needed.

Especially now her interest in politics was becoming an obsession.

In 1959, after a few years practicing as a barrister, Thatcher stood again for election, this time in the Conservative safe seat of Finchley.

Unsurprisingly, she won. More surprisingly, she soon began to skyrocket up through the party’s ranks.

By 1961, she’d been appointed secretary in the Ministry of Pensions and National Insurance.

Although her party lost power in 1964, its new leader – Ted Heath – invited her into the Shadow Cabinet: sadly not the Tory version of the Council of Doom, but what us Brits call the out-of-power party’s highest-ranking members.

That meant that, when Heath unexpectedly won the 1970 election, Margaret Thatcher became only the fifth female Cabinet Minister in British history.

It was a remarkable moment.

Despite working for a party full of men who’d never quite mentally removed the “no girls allowed” sign from their treehouses, Thatcher had ascended to one of the top positions in the land.

Little could anyone have known this was only the start.

The Iron Lady

For anyone living in Britain, the 1970s were like being on the world’s worst rollercoaster.

It was a decade when Britain teetered on the verge of bankruptcy. When powerful unions called strikes that paralyzed the country.

But for Margaret Thatcher, it was also the decade when everyone associated her primarily with milk.

In 1971, looking to make savings in the Education budget, Thatcher eliminated a postwar policy of free school milk for children.

Although it was justifiable, the optics were so bad it became a PR disaster. For the rest of her tenure, Thatcher was followed everywhere by cries of “Thatcher, milk snatcher!”

But unpleasant as this was, it was nothing compared to what was going on behind the scenes.

Thatcher and Ted Heath hated one another.

While it was partly personal, it was also Thatcher being sick of defending her government’s dreadful record. It was under Heath that the Three Day Week came in, when businesses were only allowed electricity three days a week to conserve energy.

As a result, the Conservatives lost both 1974 elections.

Suddenly, Thatcher was out of government. But now, the grocer’s daughter from Lincolnshire knew what she had to do.

She had to get rid of Heath.

These days, losing an election means stepping down as leader of your party. But, back then, you could keep right on trucking… so long as no-one challenged you to a leadership contest.

The Conservatives being the party of loyalty, no-one wanted to challenge Heath.

Except Thatcher.

The newspapers thought she was out of her mind. When Thatcher stood for leader of the Tories, it was assumed Heath would romp home to victory. But Thatcher went on the attack. Gathering the party’s right wing around her, she lambasted Heath’s dreadful record.

In February, 1975, the shock results of the first ballot came in: Thatcher had won. Now, under the Conservative Party’s weird rules, this didn’t actually make her leader. But Heath could see his position was untenable and stepped aside.

And, just like that, Thatcher became the first female leader of a major UK party. Not that anyone expected her to rise any further. In 1975, the Labour government was headed by the affable, broadly-popular Harold Wilson.

So what if Thatcher was making barnstorming anti-Communist speeches that earned her the nickname “the Iron Lady”? So what if the Tories were getting better at messaging?

With Wilson heading the Labour Party, she was probably doomed.

Unfortunately for Labour, Wilson wouldn’t be around much longer.

In 1976, Harold Wilson abruptly resigned as Prime Minister – a move now thought to have been brought on by the discovery that he had early-stage alzheimers. His replacement was a charisma-void known as James Callaghan; a guy so inept he turned a mildly pro-Labour country into rabid Tories.

Under Callaghan, Britain collapsed into economic turmoil.

There were gigantic pay freezes. Nationwide battles with overpowered unions. In late 1978, things culminated in the Winter of Discontent, a period when uncollected refuse piled high in the streets and bodies were left unburied.

It was likely the country’s postwar low point. The UK as an ungovernable mess.

It was also exactly what Thatcher needed.

On March 28, Margaret Thatcher called a no-confidence vote in Callaghan’s government, triggering an early election. As the campaign heated up, the Conservatives played a blinder, plastering London with posters of long dole queues under the caption “Labour isn’t working”.

Callaghan, meanwhile, gave the impression of someone who expected to win because, duh, his opponent was a girl.

On May 3, 1979, the Conservatives won the election by a decent margin. Not a landslide, but enough to comfortably form a government. On that day, Margaret Thatcher became not only the UK’s first female PM, but the first female leader of any major Western democracy.

As she entered 10 Downing Street, the triumphant Thatcher declared:

“Where there is discord, may we bring harmony.”

As you’re about to see, this wouldn’t exactly happen.

From the Jaws of Defeat

As 1982 dawned, it looked like Britain’s first female PM was doomed to be a one-term wonder.

In her first years in power, Thatcher had set out her governing style: antagonistic, determined, destructive.

In a weird way, she was like a 2010s tech mogul. Someone who disrupted, who broke stuff, who assembled something new from the wreckage of the old. During her later terms, the economic gains from this destruction would be enough to keep Middle England onside.

But, as her first term swept by, those gains had yet to materialize.

All anyone could see was the destruction.

More businesses were failing than at any time since the Great Depression. Unemployment was at record-breaking highs. Privatization of state assets had so far cost tens of thousands of jobs, but not yet brought visible benefits.

Despite a famous declaration in October of 1980 that “the Lady’s not for turning”, Thatcher’s closest advisors were secretly urging her to make a gigantic U-Turn, lest the Tories be stomped at the 1983 election.

It was onto this sinking ship that Argentina suddenly threw a gigantic lifesaver.

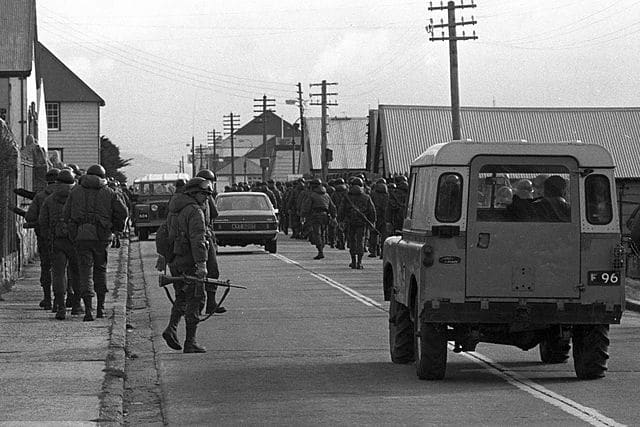

OK: quick geography lesson.

Down in the South Atlantic, about 483km off the Argentine coast, lie the Falkland Islands. Despite being nearly 13,000km from London, they’ve been a British territory since at least 1833. By 1982, though, the Falklands were only home to a declining population of 1,800.

Although Britain still claimed the territory, it refused to invest there, and the private hope of successive governments had been that the islanders would voluntarily accept Argentinian sovereignty at some point in the future.

But the military junta in Buenos Aires was tired of waiting.

On April 2, 1982, they occupied the Falklands. A few days later, they also took the British territory of South Georgia. The junta assumed London was too broke, too unwilling to send soldiers to die for the sake of a God-forsaken rock on the other side of the world.

They were nearly right. When news broke, the Cabinet’s feeling was that the Falklands would have to be surrendered.

But the junta hadn’t counted on Thatcher.

Egged on by the Navy, Thatcher declared war on Argentina. A Royal Navy flotilla was sent to retake the islands.

With that, the Falklands War began.

Today, it’s almost impossible to overstate the effect the short war had on Thatcher’s popularity. Remember how George W. Bush’s approval rating hit 92% after 9/11? Well, something similar happened here.

Thatcher’s resolute defense of British territory struck a chord with ordinary citizens.

It helped that the war was short, lasting a mere 74 days before Argentina surrendered; and that it was so one-sided. 649 Argentine troops were killed, versus 255 British troops.

But make no mistake. The iron will Thatcher displayed in the face of foreign aggression made her a hero. It elevated her profile on the international stage. Already allied with US President Ronald Reagan, she now started to look like his equal.

Come the 1983 election, Thatcher crushed Labour in a landslide.

With her powerful new mandate, the gloves were at last off.

Over her next two terms, Margaret Thatcher was going to change Britain beyond all recognition.

Battles and Troubles

Thatcher’s second term began with a powerful message: appointing Ian McGregor head of the National Coal Board. Back in 1979, Thatcher had hired McGregor to make the state-owned British Steel profitable again. McGregor had achieved this, at the loss of 95,000 jobs and the economic devastation of entire towns.

Now Thatcher was asking him to do the same for the ailing coal industry.

But while British Steel had folded to McGregor’s iron will, coal would be much tougher. The National Union of Miners was Britain’s most-powerful union – at a time when unions could break an entire premiership. It was the NUM in 1973 that had exacerbated the Three Day Week, leading to Ted Heath’s downfall. Now, they were looking to do the same to Thatcher.

Unfortunately for the NUM, Thatcher had brought to this figurative knife fight not just a gun, but a goddamn bazooka. On March 6, 1984, a local strike at Cortonwood Colliery was used by NUM president Arthur Scargil to force a general strike across the nation.

But Thatcher was prepared. Coal had been secretly stockpiled. Non-unionized firms hired to do strikebreaking. Police forces primed to fight.

The battle was on.

And it really was a battle, or series of battles.

The worst took place at Orgreave, when a mounted police charge into a crowd of strikers led to 123 serious injuries.

But the main weapon Thatcher deployed wasn’t truncheons, but time.

As the strike dragged on, laws were passed that stopped the families of striking miners from receiving welfare. In effect, Thatcher starved her enemies into submission. And submit they did. On March 3, 1985, the strike was called off. The miners returned to work, broken.

Over the next decade, McGregor and his successors closed all but 15 of Britain’s 174 deep pits. The economic engine of entire regions was wiped out, leaving jobless wastelands.

With the NUM defeated, the days of big unions bringing Britain to a standstill were over.

But although Thatcher won this war just as she had the Falklands, the other great war of her premiership would prove to be unwinnable. The Troubles were an undeclared civil war in Northern Ireland that pitted majority-Protestant unionists who wanted to stay in the UK against majority-Catholic Republicans who wanted to join Ireland proper.

When Thatcher took power, the Troubles had already been running for a decade. But they were about to get much worse.

Things really kicked off on August 27, 1979, when the IRA first assassinated a member of the Royal Family – Lord Mountbatten – before killing 18 British soldiers in a double bomb attack.

But Thatcher’s biggest test came in March of 1981.

That month, IRA prisoners – including member of Parliament Bobby Sands – began a hunger strike to force the British state to treat them as prisoners of war.

The thought horrified Thatcher, who declared the men were common criminals, saying:

“Crime is crime is crime. It is not political.”

By the time October rolled around, ten of the hunger strikers were dead, and their mistreatment had turned them into international celebrities.

It had also turned Thatcher into a Republican hate figure.

On 12 October, 1984, an IRA bomb at the Conservative conference in Brighton killed 5 people. Thatcher escaped unharmed, and made a speech the following day vowing to fight on. She hoped to inflict a decisive British victory on the forces of Republicanism.

Instead, the Troubles went supernova.

Over the next few years, the IRA bombed civilians; killed policemen with mortars; and even assassinated Thatcher’s friend, the Conservative MP Ian Gow.

It wouldn’t be until Thatcher left office that the Troubles would come to an end, thanks to the work of her successors John Major and Tony Blair. Although it was far from a defining theme of her premiership, Thatcher’s failed attempt to defeat the IRA showed the limits of the Iron Lady’s power.

Sometimes – just sometimes – perhaps the Lady should have been for turning.

The Big Bang and Beyond

Away from the wars and anti-union crusades, Maggie was also overseeing a social revolution.

Thatcherism preached hard work, personal responsibility, and economic liberalism. It promised a world in which anyone could become well off, provided they were happy to roll up their sleeves. While this may have seemed a joke to those in depressed former-mining towns, it was true for enough people to keep her in power.

One of the most-popular policies was Right to Buy, which allowed those in council housing to save up and buy the place for themselves.

But the biggest rewards fell to those who profited from the Big Bang.

As early as 1979, Thatcher had begun loosening regulations in London’s financial sector, leading to a lot of people becoming very rich.

But it was on October 27, 1986 that things really took off.

Copyright © IPPA 90500-000-01, CC BY 4.0

That was the day the City was almost completely deregulated, allowing things like foreign firms to own UK brokers; and abolishing the fixed commission on trades. Overnight, the Big Bang made 1,500 millionaires. It created iconic districts like London’s Canary Wharf. Skyscrapers began to sprout up. Money poured in.

It was the transformation of the financial sector from the bowler-hat wearing old boys club of yesteryear into the turbo-capitalist free for all of today.

Yet Thatcher’s revolution went beyond the mere confines of Britain.

Under her watch, the UK became a global player in a way it simply hadn’t been since Churchill left office. In 1984, for example, Thatcher began courting Mikhail Gorbachev, even before he became Soviet leader. During a visit to Britain, Gorbachev famously had a six hour argument with Thatcher over the benefits and ills of Communism.

When they were done, Thatcher declared “we can do business together,” and set about becoming both Gorbachev’s best friend and worst enemy in the West; urging a skeptical Ronald Reagan to work with the new Soviet premier.

Not that she let the Russian push her around.

Invited to the Soviet Union in 1987, Thatcher went on live TV and spent an hour talking about all the USSR’s failings. For citizens in Communist nations, that speech was like seeing someone articulate everything they’d been feeling for decades.

Thatcher became an overnight celebrity in the Eastern Bloc. Even today, countries like the Czech Republic consider her a British hero on par with Churchill.

But there were missteps, too.

In the latter part of the 1980s, Thatcher vehemently opposed sanctions against South Africa’s Apatheid regime.

She considered Nelson Mandela a “typical terrorist”, and proudly boasted that Britain was the only Commonwealth nation still trading with the white supremacist state.

Ouch.

Yet there were also surprise moments when she broke her own party’s line.

In the late 1980s, she became one of the first world leaders to sound the alarm on climate change: helping push for a world environmental fund, the preservation of rainforests, and the introduction of emissions targets.

Overall, then, there was enough popular stuff in the Thatcher program to ensure she cruised to an easy victory in 1987, becoming the UK’s only 20th Century leader to serve three terms.

And still she seemed destined to go on. There was even talk of her winning a possible fourth term.

But it was not to be. The woman who had overhauled Britain had already sown the seeds of her own destruction.

When the end finally came, it was going to be with a swiftness that shocked everybody.

Downfall

In the end, what brought Thatcher down was what has brought down every single Conservative Prime Minister since: Europe. On January 1, 1973, Ted Heath had taken Britain into what was then the European Economic Community – a move confirmed by a 1975 referendum.

Come the 1980s, the Conservatives were still a mostly pro-Europe party. At least in theory.

Unlike her MPs, Thatcher was rabidly anti-Europe.

At first, this was something her MPs managed as best they could. It even occasionally brought benefits, like when Thatcher reduced Britain’s budget contributions in 1984.

But it soon became a major liability.

As the continent integrated further, Thatcher became a vocal Euroskeptic, railing against the continent’s leaders. This would’ve been fine if she’d managed to get her party onside. But official policy remained pro-Europe.

In effect, Thatcher was sabotaging her own government.

The result was a string of senior ministers resigning, all contributing to a perception that the Tories were becoming dangerously incompetent. Then, just as this gigantic pile of fertilizer was starting to look extremely combustible, Thatcher threw an unrelated match onto it.

The poll tax is why Scotland to this day remains passionately anti-Tory.

A political move designed to deprive Labour councils of revenue, it abolished local tax rates, instead levying a flat tax on every adult. The upshot was that the rich saw their bills plummet, while the middle classes – the very backbone of the Thatcherite revolution – saw their costs go shooting up.

In 1989, Thatcher piloted it in Scotland ahead of a roll out across England and Wales.

It was a disaster. There were protests. Mass acts of civil disobedience.

By 1990, over 1m had refused to pay. Ministers begged Thatcher not to push ahead with the hated tax.

But, like a latter-day George III, Thatcher insisted on it.

On March 31, 1990, central London was devastated by an anti-poll tax riot. That summer, discontent brewed across the nation. Sadly, by now Maggie had become a caricature of herself. She was the Iron Lady, not for turning. Even when turning would’ve saved her political career.

Things finally came to head in October.

Following a European summit on integration, Thatcher gave an angry speech in which she replied to the idea with a shouted “No! No! No!”

In response, the pro-Europe cabinet member Geoffery Howe resigned. For such a measured man, his resignation speech was devastating, concluding that the party needed to question its loyalty to Thatcher.

At another time, Thatcher could’ve shrugged it off.

But in 1990, with poll tax riots burning the country, and a pro-European party fed-up with her Euroskepticism?

She was toast.

On November 15, the Europhile Conservative Michael Heseltine did what Thatcher had herself done to Heath all those years ago. He challenged her to a leadership contest. And, when the results came in, Thatcher saw she was doomed.

Although she’d got the most votes, it had been by a pitiable margin. As the two headed into the second round, Thatcher realized – to her profound shock – that she might lose.

So she jumped before she was pushed.

At 07:30am on November 22, 1990, Margaret Thatcher resigned as Prime Minister. At the moment she stepped down, she was the “longest continuously serving prime minister since 1827.”

She was also one of the two most-influential postwar PMs, setting an economic agenda that has pretty much lasted intact until today. Only Clement Attlee really comes close in terms of significance. And it was his long-lasting postwar settlement that Thatcher ripped up.

Yet, despite her continued significance; despite her achievement opening the door to future female leaders, Thatcher spent her years out of office bitter and unhappy.

She fumed over her betrayal by her party. Fumed over the creation of the EU.

With nowhere left to channel her prodigious energies, she turned inwards. By 2000, she was showing signs of the dementia that would soon consume her – just as alzheimers had consumed Harold Wilson before her.

By the end, the dementia rendered her mute, almost incapable of doing even the simplest action.

It’s said she liked to spend her last days staring at a painting of a Victorian hunting party. Not really doing anything, just watching the crowd of painted dogs for signs of life.

Margaret Thatcher passed away on April 8, 2013.

While the world mourned the death of a great leader, the reaction in Britain itself – where towns devastated by her economic polices still haven’t recovered – was mixed.

That week, the #2 record in the British chart was Ding, Dong, the Witch is Dead. Yet, for all the bile many heaped upon her, for all the hatred she stirred up, Thatcher’s legacy all around us. It’s from her Euroskepticism that the forces grew that would unleash Brexit. From her wave of deregulation that toady’s City of London was created.

Almost every facet of modern life that we Brits take for granted – the depressed, post-industrial towns; the “special relationship” with America; the lack of paralyzing, French-style strikes – all have their roots in Thatcherism.

In the end, then, the good and the bad of her legacy are impossible to separate.

She was who she was; with the blind faith to do both necessary things for Britain’s future… and to commit screw ups that still haunt the nation to this day. In a world without Maggie Thatcher, many would be worse off; some would be better off, but all would be able to agree on one thing.

That they were living in a completely different world from us. One in which Britain, Europe, and the former nations of the Soviet Union had very different fates.

If greatness is measured purely in terms of impact, then that surely makes her one of the greatest Prime Ministers of all.

Sources:

Biography, overview: https://www.biography.com/political-figure/margaret-thatcher

Britannica, in-depth: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Margaret-Thatcher

New Yorker profile: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/12/02/its-still-mrs-thatchers-britain

NYT obituary: https://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/09/world/europe/former-prime-minister-margaret-thatcher-of-britain-has-died.html

Guardian obituary: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2013/apr/08/margaret-thatcher-political-phenomenon-dies

Falklands War: https://www.historyextra.com/period/20th-century/falklands-war-history-facts-what-happened

Falklands and Thatcher: https://www.history.com/news/margaret-thatcher-falklands-war

Miners’ Strike: https://www.history.co.uk/article/how-thatcher-broke-the-miners-strike-but-at-what-cost

Thatcher and Northern Ireland: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-11598877

Mountbatten Assassination: https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/tv-radio-web/dead-dead-dead-the-day-lord-mountbatten-two-boys-one-woman-and-18-soldiers-died-1.3991952

The Big Bang: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-37751599

Deregulation? https://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/may/25/margaret-thatcher-deregulated-city-london

Thatcher and Gorbachev: https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2015/10/22/when-margaret-thatcher-and-mikhail-gorbachev-changed-the-world-a50435

Europe conundrum: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2020/feb/29/article-young-boris-johnson-margaret-thatcher-no-no-no

Thatcher’s downfall: https://in.reuters.com/article/britain-thatcher-fall/witness-thatchers-dramatic-1990-fall-stabbed-in-the-front-idINDEE9370AX20130408

Poll tax: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-38382416

NYT review of her authorized bio, good details: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/12/books/review/margaret-thatcher-the-authorized-biography-herself-alone-charles-moore.html

FT version of the above (paywall): https://www.ft.com/content/059393b0-f19b-11e9-a55a-30afa498db1b

Andrew Marr on the same: https://www.newstatesman.com/Margaret-Thatcher-book-review-andrew-marr-biography-charles-moore-Volume-Three-Herself-Alone

Thatcher and climate change: https://theecologist.org/2018/aug/21/how-margaret-thatcher-came-sound-climate-alarm

Oxford University: https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2013-04-09-margaret-thatcher-1925-2013

Wilson Resignation: https://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/harold_wilson_resigns/zjhrrj6

1 Comment

she was a vile creature, he damage is still felt to this day. one of the worst