When one thinks of the First World War, two images come to mind. The war on the ground was a bloody stalemate, with modern weapons but outdated tactics, that led millions of soldiers to the slaughter.

By contrast, the war in the air is still heavily romanticized over a hundred years later. Barely a decade after the Wright Brothers first demonstrated a functional airplane, the combatants of the First World War had developed a number of aircraft for military purposes. Most famous of all, of course, were the fighter planes. The rumbling loud devices, built out of wood with canvas wings and an open cockpit may seem ridiculous by modern standards, but during the war, they were at the cutting edge of technology. Fighter pilots were celebrated heroes, the last knights of Europe, who “jousted” at each other with machine guns in the name of honor.

No one typified this image better than Manfred von Richthofen. With 80 confirmed aerial victories, Richthofen was the leading ace of the First World War. More than that, he was a national celebrity in Germany. The public followed his exploits in newspapers and infantry soldiers carried pictures of him in their pockets. Richthofen (pronounced Reek-toe-fen) followed his own code of chivalry that earned him the respect of both his fellow pilots and his enemies, who nevertheless learned to fear the appearance of his brightly colored red airplane in the skies.

The Red Baron, as he is commonly known, has become a cultural touchstone, easily the most famous German soldier of the First World War, and one of the most celebrated fighter pilots of all time.

Early Life

Manfred von Richthofen was born on May 2nd, 1892, near Breslau in Lower Silesia, which is today part of Poland. He was part of a prominent Prussian aristocratic family, or Junker. He had the noble title “Freiherr” which translates into Baron in English. Like many children of his social class, Richthofen was well educated, and excelled at outdoor pursuits such as horseback riding and hunting. He was also well regarded as a gymnast in school, particularly on the parallel bars, where he was noted for his fast reflexes.

Young Manfred was destined for military service from a young age, beginning his cadet training in 1904 at age 11. When he graduated in 1911, he received a commission into a cavalry regiment, an appropriate posting for someone of his position. But he didn’t have time to settle into peacetime military life for long, however.

The Great War

For hundreds of years, the major powers of Europe sought to maintain a balance of power with each other. After the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, this was achieved by an almost constantly shifting series of alliances between the principle countries of Europe. With a few exceptions, this complicated system worked to maintain peace throughout the continent over the course of the following 100 years. But the apple cart was upset in 1871, when Prussia joined together with many of the surrounding German speaking provinces to form the German Empire, with the former King of Prussia now the German Emperor, or Kaiser. The new state sought to assert itself as a major player in world affairs, building a substantial military force and establishing a colonial empire in Africa and East Asia.

This alarmed France and Great Britain, who formed an alliance with each other and with the Russian Empire to defend against German aggression. Germany, in turn, allied itself with its southern neighbor, the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The balance of power was maintained in this way at the start of the 20th century, but it meant that any regional conflict involving any of the major powers would quickly escalate into a continent spanning war. That was exactly what happened in the summer of 1914, when the Austro-Hungarian Empire blamed Serbia for the assassination of the heir to the Austrian throne, and declared war. Serbia was allied with Russia, who declared war on Austria, and that drug everyone else into the conflict, and for the first time in a hundred years, the entirety of Europe was at war.

Military technology had changed drastically in the last hundred years, and it quickly became apparent that cavalry regiments were worse than useless against machine guns and trench warfare. The German cavalry units were all dismounted and utilized in support roles behind the front lines. Manfred von Richthofen chafed at this, eager to get into combat himself. His chance came in May 1915, when he received a transfer to the Imperial German Air Service. The young Baron was going to learn how to fly airplanes.

The Baron Takes Flight

Richthofen had joined the German Air Force at a time of great transition in aviation history. All the major combatants were trying to figure out how to best employ this new technology in the war effort. The obvious answer was to mount machine guns on the planes, but the engineers still needed to overcome the rather glaring problem of avoiding shooting off your own propeller when firing the gun directly forwards. The Germans figured it out first: they invented the synchronisation gear, a mechanism that allowed the machine gun to fire between the blades of the propeller. This gave them an initial period of air superiority, known as the “Fokker Scourge.” Before long, purpose built “fighter” planes were being produced and the war in the air escalated as pilots started trying to shoot each other down.

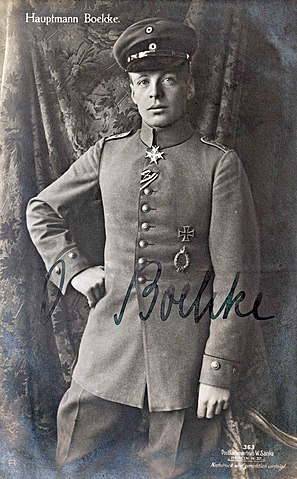

In August 1916, Richthofen was flying two seater bomber planes on the Eastern Front when he was visited by Oswald Boelcke. Boelcke was looking for pilots to join his newly formed fighter squadron, and he signed up Richthofen.

Boelcke was a legend in the German Air Force. He was the original fighter ace, having shot down 40 planes. He was also one of the first pilots to develop aerial tactics for his squadron, developing a series of maxims known as the “Dicta Boelcke” that became standard practice for all pilots in the First World War, things like flying with the sun behind you so your enemy can’t see you coming, attacking from behind at close range, and attacking in a formation instead of as individual planes. Richthofen would take the Dicta Boelcke to heart very early in his fighter career, and gave it credit for why he was so successful.

Richthofen got his first confirmed kill on September 17th, 1916, and had shot down five more by October 28th, when Oswald Boelcke was killed in a midair collision with another German plane. By January 1917 he had shot down 16 planes, and received the Pour le Merite, Germany’s highest award for gallantry, also known as the Blue Max. That same month, he was named commander of his own squadron, Jasta 11, and thus embarked on the path of becoming a legend.

The Red Baron

Soon after assuming command of Jasta 11, Richthofen got the idea in his head to paint his airplane bright red. No one is really sure why he did it, but word soon spread across Europe, and Allied pilots grew to fear the appearance of Richthofen’s red airplane in battle, as it usually meant death to his enemies. German newspapers, on the other hand, loved the paint job, they soon began referring to him as Der Rote Kampfflieger, “The Red Fighter Pilot.” It was the Allies, however, that bestowed upon him his most famous nickname-The Red Baron.

Jasta 11 began to rack up aircraft kills, and Richthofen led the way. During “Bloody April” 1917, Richthofen shot down 22 British planes, including 4 in one day. He now had 52 aerial victories. He was soon promoted again, to command a fighter wing of four squadrons. The other German pilots, seeking to emulate the Baron, began painting their planes in various bright colors as well. The air wing soon became known as “Richthofen’s Flying Circus.”

Richthofen was a master of a very difficult and dangerous craft. In the First World War, air to air combat was a game of high stakes maneuvers conducted at close range. When squadrons of planes engaged each other, they broke off into a series of one on one engagements that pilots called “dogfights.” (Author’s Note: This footage is from the 1930 Howard Hughes Film “Hell’s Angels”, which is in the public domain.) The goal was to get directly behind your opponent, also known as being in the plane’s “six o’clock position,” and fire your machine guns at close range (since the guns were fairly inaccurate the farther away you were) until you sufficiently damaged the plane to cause it to fall out of the sky, or you shot the pilot.

This was not as easy as you might think. These planes had an open cockpit, meaning that the pilots were exposed to wind speeds in excess of 150 kilometers per hour, in frigid temperatures, often compounded by wet weather. You had to pay attention to both the instruments in the cockpit as well as the airspace all around you, to avoid crashing into the ground or other aircraft. And of course you had to contend with the fact that people both on the ground and in other planes were shooting at you.

Richthofen was not a particularly acrobatic flyer, leaving the complicated maneuvers to pilots like his younger brother, Lothar. Where he excelled was his skill as a tactician and a marksman. He didn’t have to outfly his enemies when he could outsmart and outshoot them. He was also noted for his chivalrous conduct. Once he was sure that the enemy plane was crippled, he stopped shooting at it, he avoided strafing downed pilots who survived their crash landing, calling himself a “sportsman, not a butcher.” He insisted on entertaining captured Allied pilots with dinner and drinks before they were sent off to prisoner of war camps. This was considered only proper behavior by him, something that was expected from a German nobleman.

Germany’s Hero

Richthofen was seriously wounded in the head on July 6th, 1917, while flying a combat mission. Though suffering from temporary partial blindness, he was able to force his airplane to land essentially intact behind German lines in Belgium before being rushed to a hospital. Doctors had to perform several surgeries to remove skull fragments from his brain. He was able to recover enough to be back in the cockpit by July 25th, but the headaches and post flight nausea he suffered in the aftermath were so bad that he was forced to take medical leave for almost two months in the fall of 1917.

While grounded, Richthofen authored an “autobiography” that was heavily censored and edited by German propagandists to paint the war and his actions in a proper patriotic and positive light. By this time, the German government was sanctioning a cult of hero worship based around the leading German fighter aces in general, and Richthofen in particular. Newspapers printed stories of his exploits, every time he claimed a kill, it was front page news. Some newspapers even had scoresheets tallying the kill totals of the top German pilots, with Richthofen by now at the top. Soldiers in the trenches could be found carrying his picture in their pockets, and he was swarmed by well wishers and fans wherever he went. There was serious consideration to grounding him permanently, as he was held in such high regard by the German people that it was feared his death in combat would weaken public morale, perhaps jeopardizing the entire war effort. But Richthofen wouldn’t hear of it. He argued that, like the common soldier in the trenches, he must take his chances like everyone else.

Richthofen returned to the air in November 1917, but he did it in the cockpit of a new airplane. The Fokker Dr. I Triplane was much more powerful than anything the Germans had flown before, and Richthofen immediately recommended that the entire Air Force be equipped with them as soon as possible. It is this image, that of the red painted triplane, that has come to be most associated with the Red Baron.

Luck Runs Out

In the spring of 1918, Germany made her bid to win the war with one decisive blow. In late 1917, Russia, now under the control of Lenin and the Communists, had signed a peace treaty with the Central Powers, ending the war on the Eastern Front. At the same time, the United States of America entered the war on the side of the Allies. General Erich Ludendorff, now the leading figure in most of the German war effort, knew that rapidly transferring troops from east to west and smashing the Allied position on the Western Front, before the Americans could arrive in force, was essential. In March, they launched their Spring Offensive, breaking through the Allied lines and racing towards Paris. The war in the air was considered important to this offensive, so Richthofen’s squadrons were busy. In a little less than a month, Richthofen shot down 15 Allied planes, including several of the new British built Sopwith Camels that were built specifically to counter the air superiority Richthofen’s squadrons had enjoyed in 1917.

On April 20th, 1918, during a dogfight, Richthofen shot down two Camels within three minutes of each other, scoring his 79th and 80th kills. The next day, April 21st, Richthofen’s cousin, Wolfram, was joining them on his first mission. Because he was new, Richthofen ordered his cousin to stay out of the fighting, that when contact with the enemy was made, he was to circle above the battle and watch.

At about 11AM, Richthofen’s planes tangled with the 209th Squadron of the Royal Air Force, commanded by Captain Roy Brown. Wolfram von Richthofen did what his cousin had ordered and circled above the fray. As it happened, one of the RAF pilots, Wilfred May, had been ordered by Captain Brown to do the same thing, as he was also new. May saw Wolfram’s plane all by itself near his position and decided to attack him.

The Red Baron looked up and saw his cousin under attack, and immediately flew to his rescue, firing on May and forcing him to break away from the fight. Richthofen continued to chase May as he descended towards the ground. Captain Roy Brown saw what was happening and attempted to intervene, firing a burst on Richthofen from above before having to pull up sharply to avoid hitting the ground. Richthofen briefly moved to avoid Brown’s attack, then, inexplicably, turned to go after May again, despite the British pilot being far away from the battle and dangerously close to the ground, occupied by Allied soldiers.

There are many theories as to why Richthofen, always the cautious and meticulous pilot, had behaved in this reckless way, something that he would have upbraided his subordinates for. It is believed that the head injury that Richthofen had suffered in July 1917 had caused permanent brain damage, impacting his ability to make rational judgments about what was safe and what wasn’t. His target fixation on May’s plan is a possible indicator of this brain damage. He may also have been suffering from acute combat stress, an overload based on almost two continuous years of aerial combat, watching his closest friends and comrades die, and the near fatal maiming of his brother. This could have put him in a dissociative, perhaps even suicidal state, where either he wasn’t aware of the danger posed, or simply didn’t care. It is also entirely possible that, with the Spring Offensive in full motion, Richthofen didn’t realize where the front lines were, and didn’t know he had strayed into enemy territory. Or it could have been a combination of all of these factors. There’s simply no way to know.

What we do know is that, shortly after avoiding the attack by Captain Brown, Richthofen was fired on by soldiers on the ground with both rifles and machine guns. A single bullet struck Richthofen from behind, causing massive damage to his vital organs. He was able to land his Triplane in a field near the Somme River, controlled by Australian troops. Some of them rushed to his plane, but by the time they arrived, the Red Baron was dead, two weeks shy of his 26th birthday.

Aftermath

A nearby squadron of the Australian Royal Flying Corps took responsibility for Richthofen’s body. Most Allied pilots greatly respected the Baron, and the Australians honored him the next day by burying him with full military honors at a small cemetery outside of Amiens. Many other squadrons sent wreaths, including one that was inscribed “To Our Gallant and Worthy Foe.”

Just as the German government feared, the death of Manfred von Richthoven was met with widespread shock and despair. The Spring Offensive fizzled out soon after his death, and over the summer, the Allies began to regain all the territory the Germans had taken, and then collapsed their main defensive line, pushing them back towards Germany itself. This caused riots in Berlin that forced the Kaiser to abdicate and for the German government to sue for peace. The First World War ended on November 11th, 1918, when the Armistice came into effect.

Richthofen’s triplane was torn apart by souvenir hunters, in fact, none of his planes are believed to exist intact today, as planes of that era were considerably more fragile than the aluminum built planes of later generations. Captain Roy Brown was officially credited with shooting down Richthofen’s plane, although modern historical consensus is that Richthofen was actually killed by ground fire. Wolfram von Richthofen survived to the end of the war and would go on to become a senior commander in the German Luftwaffe during World War II.

Richthofen’s body was moved three times from its original resting place. In the early 1920s Richthofen was moved by the French to a military cemetery in Fricourt. Then in 1925, his brother Bolko had the remains taken to Germany, to be buried in Berlin at a military cemetery along with many other famous German soldiers. The cemetery was situated on the border between West and East Berlin during the Cold War, and Richthofen’s gravestone suffered damage from bullets fired by Soviet guards trying to prevent people from crossing the Berlin Wall. In 1975, the Richthofen family moved his body to a family plot in the West German city of Wiesbaden, where it is today.

Richthofen’s larger than life persona persisted well after his death. He is one of the most recognizable figures of the First World War, and perhaps one of the most famous fighter pilots of all time. The name “The Red Baron” is something most everyone has heard, even if they don’t know anything about the real life Manfred von Richthofen. Perhaps the most indelible way he has been immortalized is by the comic book strip “Peanuts.” In the comic, Snoopy often imagines he is flying a Sopwith Camel (which is actually his doghouse), and his great rival, the Red Baron, continually shoots him down, much to Snoopy’s chagrin.

Manfred von Richthofen had an outsized impact on aviation history. He helped lay the foundation for future fighter pilots to follow, inventing tactics that are still taught to military pilots 100 years later. More than that, he helped forge the image of the fighter pilot into the public consciousness. In the modern mechanical horror of war, he was the last knight, who obeyed the ancient code of chivalry and treated his enemies with respect and honor. He may have died tragically at the age of 25, but his actions and persona have ensured that his name and deeds will live on forever.

Additional Sources

Manfred von Richthofen: The Man and the Aircraft He Flew, David Baker, 1991, Voyageur Press