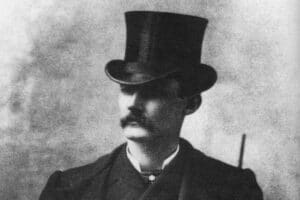

“In no outward particular did this man indicate the cowboy by birth and training, the gambler by choice, and the slayer of men by force of circumstances. And yet Luke Short did all that.”

Those words from an obituary following Short’s death in 1893 perfectly summed up what was special about him. Short by name and short by stature, Luke was a small man who liked to be well-groomed and well-dressed. If you looked at him, you wouldn’t think Wild West gunslinger. You certainly wouldn’t be intimidated by him. But that is where you would be making a mistake, possibly even a fatal one. Multiple men found out the hard way that the gentlemanly façade of Luke Short hid a ruthless persona that struck without hesitation when it was threatened.

Despite not being as famous as some of his friends such as Wyatt Earp or Bat Masterson, Short was involved in several high-profile gunfights that were the talk of the town in their day, especially the one against Jim Courtright. And, let’s not forget, he was the one responsible for putting together the Dodge City Peace Commission which was, basically, the western version of the Avengers. So today we’ll take a look at the life of Luke Short, the Deadly Dandy of the Wild West.

The Cowboy Years

Luke L. Short was born on January 22, 1854, in Polk County, Arkansas, the fifth of ten children of Josiah Washington Short and Hetty Brumley. We’re not sure what his middle initial stood for, although some places will say it was Lamar and that he was actually born in Mississippi. That’s because there was one biography from the 1960s that got a lot of stuff wrong and others later used it as a source and perpetuated the mistakes, but they went against the census records and, more importantly, the information provided by Luke Short himself in two interviews he gave about his early life.

In 1859, the family packed up and moved to Texas, in Montague County. This was a dangerous time and place to be a settler due to violent raids by the Comanche and Apache that often resulted in bloodshed and even murder. In 1862, Short had his own close encounter when his father was attacked and wounded by arrows. Young Luke ran into the house to get his father’s gun but was too small to lift it so he dragged it on the ground and brought it to his older brother. By that point, his father had managed to make his way into the house and, with the help of Luke’s brother, drove the raiders away. Everyone was fine in the end, but it left Short with a lifelong aversion to Native Americans.

One of the few accounts that covered Short’s childhood came from one of his friends and fellow Wild West icon – Bat Masterson, who lived until the 1920s and became a reporter and columnist in New York City, full bio on him available if you want it. How accurate it was we can’t say, but Masterson wrote that “Luke had received none of the advantages of a school in his younger days; he could hardly write his name legibly. Indeed, it was doubtful if he had ever seen a schoolhouse until he reached man’s estate. But he could ride a bronco and throw a lariat; he could shoot both fast and straight and was not afraid.”

That being said, Masterson was careful to mention that Short perfected his education during adulthood, specifying that “at the time of his death, he was an exceptionally well-read man. He could write an excellent letter, always used good English when talking, and could quote Shakespeare, Byron, Goldsmith, and Longfellow better and more accurately than most scholars.”

In 1869, like many other boys his age, the 15-year-old Luke began working as a cowboy. Cattle drives were big business in those days because the famed Texas longhorn was popular across the country so the same cattle would fetch much higher prices in nearby states such as Kansas or Wyoming than they would in their native Texas. However, such trips were also fraught with dangers – cowboys had to be on the constant lookout for rustlers, Native Americans, and wild animals. Despite the perils, teenage Luke went on multiple cattle drives between 1869 and 1875. He usually relied on the Chisholm Trail, which took him from Texas to Abilene, Kansas.

Abilene, back in those days, was the kind of town that kept the Wild West wild. It became very prosperous due to the cattle trade but also had a constant influx of cowboys looking to blow off some serious steam once their drives were over. They had just spent months in the open wild, and traveled hundreds of treacherous miles with nothing but each other and thousands of cattle for company. But now their job was done, they were flushed with cash and looking to get rowdy and a town like Abilene was more than happy to provide all the necessary amenities. Here is how it was described in Short’s own obituary:

“Abilene…was a great town not so many years ago…Thither went the cowboy of the early times to blow in his wages and blow up the town. It was a paradise of variety shows and gambling establishments. Everything was wide open and everything went.”

With those kinds of temptations all around him, it wasn’t surprising that Short chose to indulge in a vice or two to get the full cowboy experience. It was simply a matter of which one would he choose: cards, booze, prostitutes, or a nice little mix of all three?

As it turned out, gambling was Short’s pastime of choice. Again, the same obituary described his attitude in those early days:

“[Short] was known even then as a daring gambler who would stake his last cent on the turn of a card. He was a man of unquestioned courage, capable of holding his own with the wild spirits who resorted there…[He had a] quiet, easy manner [which] made him friends. He never sought a quarrel, but he never allowed anybody to tread on his toes, and once the fighting spirit was aroused there was nothing more to be dreaded than Luke Short.”

Unfortunately, those early years of Short’s life are too poorly documented for us to know details about the trouble he got up to. There is one exception, though – one daring standoff that supposedly occurred in Socorro, New Mexico. To be honest, this story is so outlandish that it would feel forced in a cheesy Western. More than likely, it was the product of a journalist with an overactive imagination who wanted to show off Luke Short’s cowboy bona fides, but it’s too good not to include it.

When this supposedly happened around 1872, Socorro had just established the first U.S. Court in New Mexico. But people around there were still used to living outside the written letter of the law; where frontier justice was the only justice. One day, a prominent local citizen was being tried for murder. The prosecutor, a young attorney from Kansas, brought out a witness to take the stand. During his testimony, the prosecutor asked a question, and the witness, looking out at numerous threatening faces in the crowd, hesitated. The judge told the prosecutor to ask again and make it “more explicit,” but the biggest, angriest man in the crowd got up and told the attorney: “If you ask that question again you will not live to hear the answer.”

At that point, the sound of about half a dozen revolvers cocking filled the courtroom, followed by complete silence. To his eternal credit, the attorney did not back down. He stated that he came to New Mexico knowing the dangers that awaited him and that he would repeat the question if there was another man present who would tell his wife that he died doing his duty.

At least one onlooker was moved by his brave words – “a young man smooth of face, with a slim figure and in fact the general appearance of a boy just from school.” He stood up and said:

“I am a stranger here, but if you ask that question and die, and I live, I will tell your wife that you died doing your duty; more I will tell her that you did not die alone.”

And, with those words, he drew and cocked his own revolvers and aimed them at the stunned men in the crowd. And the attorney asked the question again without incident…and the witness answered and the accused was convicted of murder…and everyone lived happily ever after…And that stranger’s name was Luke Short.

The Soldier Years

So yeah, this was probably a tall tale, and there are a few more to come since the next years of Short’s life are also a bit fuzzy. During the mid-1870s, Short stopped doing cattle drives and began roaming the great outdoors. He explored the Black Hills for a while before traveling to Nebraska where, according to Bat Masterson again, Short got involved with the Sioux…sort of. He established a trading ranch in Nebraska, close to the border with South Dakota where the reservation was. The Sioux would leave the reservation and cross state lines so they could get wasted, trading buffalo hides in exchange for gallons of whisky.

This was a very profitable endeavor for Short, seeing as he could sell each hide for about ten dollars, while a gallon of whisky only cost him around 90 cents. However, the US Government was none too pleased with his actions. This was just after the end of the Great Sioux War and tensions were still high. The agents in the area were afraid that a bunch of angry, drunk Sioux warriors running around would cause another uprising. But, at the same time, Short’s ranch was in Nebraska, so it was out of their jurisdiction.

The government agents sent word to the military commander in Omaha who, supposedly, sent an entire cavalry company to apprehend Luke Short and shut down his whisky operation. They arrested him and put him on the train to Omaha. The details get a bit murky here, but Short somehow escaped during the ride and the army wasn’t too bothered about catching him, as long as he stopped selling booze.

This story is all well and good, but it does contradict some other contemporary accounts which stated that Luke Short had been a scout for the army as early as 1876. In fact, the obituary of the Fort Worth Gazette described him as “one of the bravest and most trusted scouts in the employ of the government, and many a time while acting in his capacity he showed acts of bravery…He traveled over a wild country on many different occasions where other men had refused to go. He was in the employ of the government for several years and retired from service sometime in the 70s.”

The Omaha Daily Bee went a step further and described Short’s “most famous feat of arms” which supposedly occurred in 1876. The scout was carrying dispatches from headquarters to a remote outpost when he was waylaid by 15 Sioux. Here’s what happened:

“The first intimation he had of their presence, as he rode by, was to hear the crack, crack of their rifles and the singing of the bullets around his head. Putting spurs to his horse, he rode straight in the direction of the outpost, turning in the saddle to look for the [Sioux]. Soon they appeared from behind the crags, all riding straight for him. Short returned their fire and dropped the three foremost in quick succession with as many bullets…The survivors urged their ponies and two better mounted and bolder than the others were closing in on him. [The brave scout], deliberately checking his horse’s pace, [turned in his saddle and] dropped the two [Sioux] one after the other.” The remaining warriors “became cautious and contented themselves with taking long-distance shots at the scout, who was soon out of range and safe in camp with his dispatches.”

Certainly makes for an exciting story, but the reality is that the only military career of Luke Short that is corroborated by records took place in October 1878 and lasted only for two weeks. Between 6-8 October, Short was paid $30 as a dispatch courier who delivered a message from Ogallala to Major Thomas Tipton Thornburgh in the field. Then, between October 9 and October 20, he continued working as a civilian scout, earning another $40. Not quite as heroic although, according to Short himself, he rode 200 miles straight to reach Thornburgh in time and warn him that a Sioux army of 7,000 warriors was coming from the north, thus saving the lives of the major and his 500 men.

The Gambler Years

We do have a better idea of Short’s movements once he left the army and decided to become a full-time gambler. He traveled to Colorado where, according to the 1880 census, he was listed as a clerk living in Buena Vista, Chaffee County. However, he preferred to spend his time in nearby Leadville which had more of that classic, Wild West rough-and-tumble vibe that attracted guys like Short.

Here we have another classic “Short story” which has been retold and embellished over the years, but we’ll stick with the original provided by Bat Masterson. One day, Luke was gambling in Leadville when another man who was bigger, angrier, and had a killer reputation attempted to “take some liberty” with Short’s bet.

At first, Luke was polite, simply asking the man to keep his hands to himself but, of course, this only set him off even further. Trying to avoid a fight in his place, the dealer offered to make the bet good for both of them, but Short refused this:

“‘You will not make anything good to me. That is my bet, and I will not permit anyone to take it.’

‘You insignificant little shrimp,’ growled the bad man, at the same time reaching for his canister. ‘I will shoot your hand off if you dare to put it on that bet.’

But he didn’t. Nor did he get his pistol out of his hip pocket. For, quicker than a flash, Luke had jammed his own pistol into the bad man’s face and pulled the trigger, and the bad man rolled over on the floor. The bullet passed through his cheek but, luckily, did not kill him.”

From that point on, Short became a welcomed guest in all the gambling houses because he kept the peace. He learned faro and became a dealer, too, to make some extra cash. But, alas, the life of a gambler is a nomadic one, so by 1881 Short had already moved on to the next town – another quintessential Wild West settlement called Tombstone, Arizona.

Here is where Short met and befriended the man who would tell his tale, Bat Masterson, but also another famed gunslinger – Wyatt Earp. It is also where Short had his first notorious gunfight with another dangerous shooter named Charlie Storms. But since Masterson was actually present for this one, we can rely on his account:

“Storms did not know Short and, like the bad man in Leadville, had sized him up as an insignificant-looking fellow whom he could slap in the face without expecting a return. Both men were about to pull their pistols when I jumped between them and grabbed Storms, at the same time requesting Luke not to shoot… When Storms and I reached the street, I advised him to go to his room and sleep…

He asked me to accompany him to his room, which I did, and after seeing him safely in his apartments, where I supposed he could go to bed, I returned to where Short was. I was just explaining to Luke that Storms was a very decent sort of man when, lo and behold! There he stood before us. Without saying a word, he took hold of Luke’s arm and pulled him off the sidewalk where he had been standing, at the same time pulling his pistol, Colt’s cut-off, 45 caliber, single-action; but like the Leadvillian, he was too slow, although he succeeded in getting his pistol out. Luke stuck the muzzle of his own pistol against Storms’ heart and pulled the trigger. The bullet tore the heart, and as he fell, Luke shot him again. Storms was dead when he hit the ground. Luke was given a preliminary hearing before a magistrate and exonerated.”

The Dodge City Years

Just like Colorado, Short’s stay in Tombstone was…well, short. By 1882, he had already moved on to yet another colorful location – Dodge City, Kansas. Little did Short know that he was about to trigger one of the most notorious feuds in Wild West history – the Dodge City War.

Back in 1882, Luke Short arrived in Dodge City with the same intent as always – play some cards, deal some faro, and make some money. There was a guy named William Harris he knew from Tombstone who got him a job as a dealer at his gambling house – the infamous Long Branch Saloon. Short liked it there so much that, by 1883, he had become part owner, so now he had a vested interest in garnering as much business as possible for the saloon. One swell idea he had was to hire a pretty young lady to play the piano, which really brought in the crowds.

The problem here was that more patrons inside the Long Branch meant fewer patrons for all the other saloons and bars that dotted the city’s Front Street. This was a particular annoyance for the Alamo Saloon, right across the street from the Long Branch, and its owner, A. B. Webster, who also happened to be the city’s mayor.

Using his influence, Webster passed an ordinance forbidding music in saloons although his tavern was conveniently exempted from the rule. When Short tried to hire new musicians, they were promptly arrested, which led to a confrontation between Short and a police officer where shots were fired. Nobody was hurt, but the following day Short was told to get the hell out of Dodge and put on a train to Kansas City. If he were to return, bad things would happen.

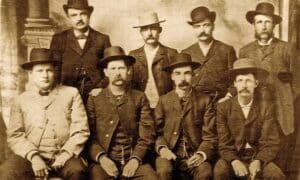

Other people might have taken the L and walked away, but not Luke Short. He had some friends of his own he could rely on, so he sent messages to Bat Masterson, Wyatt Earp, and a few others and, before you knew it, they were on the train heading for Dodge City.

Earp was already a well-known gunfighter and the others all carried their own fearsome reputations. The mayor and his cronies might have been okay strong-arming one guy out of his business, but they weren’t as enthusiastic about getting involved in a war with a whole posse. Earp alone attended a meeting with the city council and made it clear that they were willing to do whatever was necessary. He told them:

“We’re here to see that Luke gets an even break, and we can stay indefinitely. Does he get it?”

He did. Luke Short returned to Dodge City safely and stayed on for a few more months until he sold his shares in the Long Branch Saloon and moved on to greener pastures. And so, one of the frontier’s most legendary feuds ended without any bloodshed. A true rarity in those days, commemorated by one of the most famous photos in Wild West history – Luke Short and his buddies, dubbed the Dodge City Peace Commission.

The Final Years

After Dodge City, Short relocated to Fort Worth, Texas, where a similar scenario played out, albeit far more successfully. By the end of 1884, he was part owner of one of the biggest saloons in the state – the White Elephant.

His friend, Bat Masterson, got Short into sports betting, particularly boxing and horse racing. He bought stakes in racehorses and, according to one newspaper article, even rode one once during a race. Luke met and married a young woman named Hattie Buck in 1887. Things were going well, but they almost came to an end at the hands of a man named Jim Courtright.

On paper, Courtright was a lawman, having served as Fort Worth’s first city marshal during the mid-1870s. In reality, though, Courtright was a killer with a badge. As a marshal, when Fort Worth was still young and lawless, Courtright policed one of the most dangerous areas in the country, which was so violent that it became known as Hell’s Half Acre. This made him feared throughout the town so, once his marshal days were over, Courtright started a protection racket – you wanted to run a saloon or gambling den in Fort Worth and you didn’t want any problems, you paid him.

This didn’t work for Luke Short. He was not interested in Courtright’s protection services, fully confident that he could sling his own gun, should the need arise.

Well…the need arose on February 8, 1887. It was late in the evening, Courtright was drunk and angry and called out Short, who went outside without hesitation. Few, if any words were exchanged. Both men knew what this was about and they drew their guns. Some say that Courtright’s Colt.45 caught on his watch chain. Others that Short was simply faster. Either way, the result was the same – Short outdrew Courtright and shot him four or five times, killing him before he hit the ground. Short was arrested immediately after but, once again, he was exonerated when the grand jury refused to indict him, ruling it justifiable homicide.

The reputation of Luke Short as one of the Wild West’s most dangerous gunslingers had been firmly cemented, but he did not get to enjoy it for long. Luke Short might not have died with his boots on, as many of his compatriots did, but he still died young. Later that same year, Short sold his stake in the White Elephant and, together with a partner named Jake Johnson, opened an even grander saloon called the Palais Royal.

However, just a couple of years later, his health began deteriorating fast, so Short traded the hustle & bustle of the city for the serenity and healing waters of Geuda Springs, Kansas. They only delayed the inevitable. Luke Short died on September 8, 1893, aged 39. His obituary listed his cause of death as “dropsy of the bowels” and claimed he killed 11 men. Short’s body was taken back to Fort Worth and buried in Oakwood Cemetery, just a few sections away from his most infamous rival, Jim Courtright.