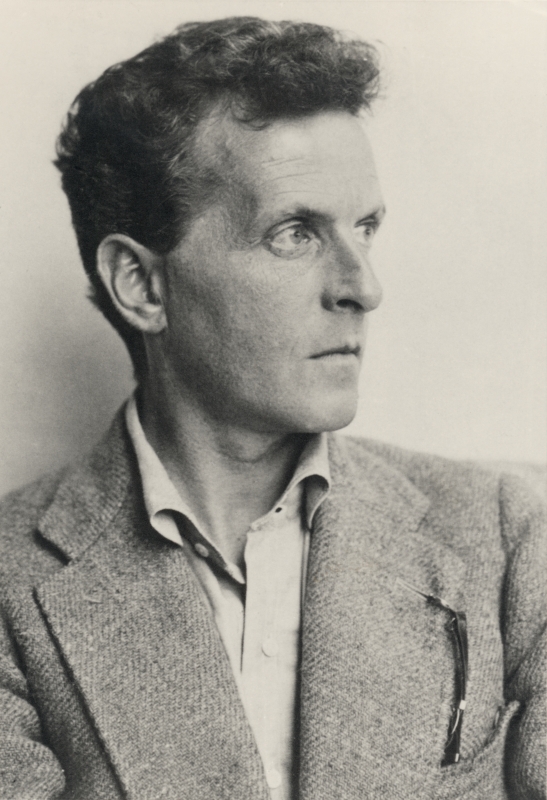

It’s one thing to be lauded as being at the top of your profession, but it’s a different sort of mind that belongs to someone who just quits for a while because they think they’ve already solved all the problems and answered all the discussions in their field.

That’s exactly what Ludwig Wittgenstein did after he published his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus in 1922. It would be the only book he’d publish in his lifetime, and with it, he was convinced that he’d finished the discussion about philosophy. So, he did what anyone would do after they’ve finished: they quit.

His hiatus wouldn’t last long, but it’s a fascinating glimpse into the man who would be remembered as one of the 20th century’s greatest philosophers. He was a self-loathing genius, a man born into wealth and the aristocracy, a man who knew all too well what it was like to have everything taken away in the blink of an eye. He gave away a huge amount of money, fought and lived through World Wars, saw the darkest side of human nature — and through it all, he struggled to make sense of it. He may not have solved all the problems of philosophy, but he definitely gave the world something to think about.

Did he create Hitler and the Third Reich?

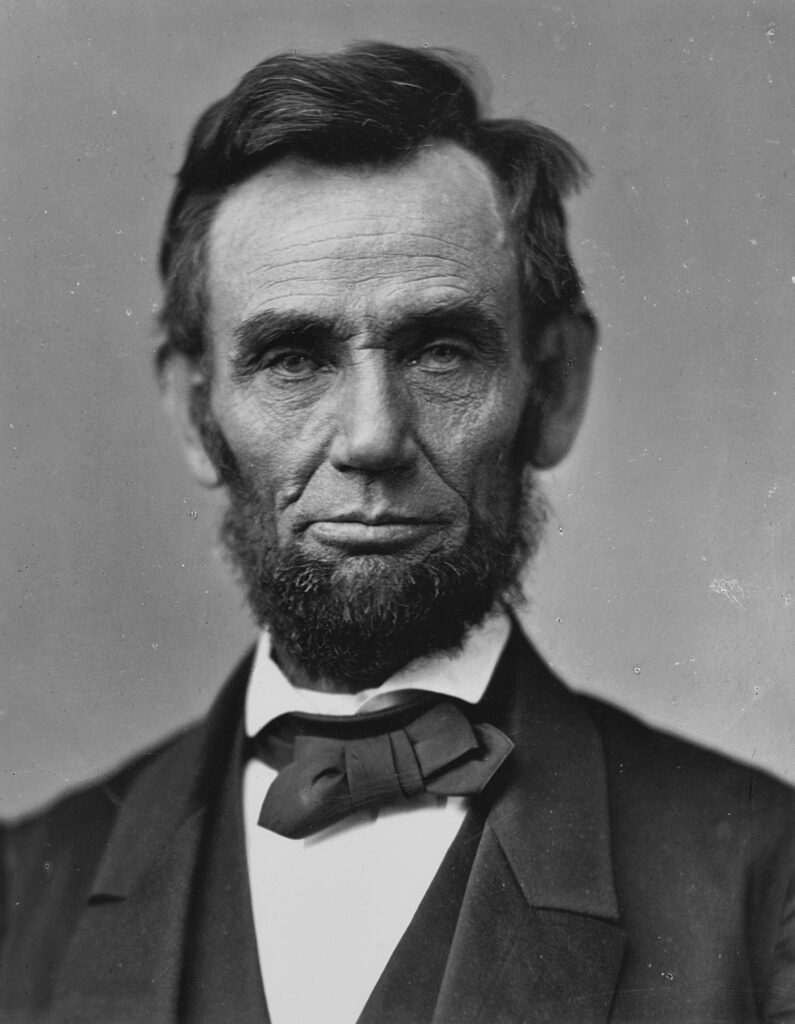

Ludwig Wittgenstein was the youngest of a very wealthy family, but that’s not to say that he belonged to old money. His father, Karl, was the son of a wool merchant and spent his early life much like the rest of us — rebelling against his own father’s wishes and working some strange, odd jobs before finally falling into where he needed to be. At one point, he even headed to the US with nothing but a violin, hoping to make a living as an entertainer. Unfortunately for the young Karl, the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln put a hold on all forms of public entertainment, and he was forced to find work as a barkeeper and a teacher.

He eventually returned to his home in Vienna, was reconciled with his parents, and was hired to work as a draftsman on the construction of a steel mill. His elders had their doubts, but he was “extraordinarily able and industrious,” and he impressed them even further when he developed a knack for sourcing steel and iron during a period of economic crisis. It wasn’t long before he was making investments, profiting from the growth of the rails, and finally making a fortune off the 1878 war between Russia and Turkey.

By the time Ludwig Wittgenstein was born in 1889, his family had money and influence. They moved through all the social circles of the upper echelons of Vienna’s cultural and intellectual crowds, and their wealth only continued to grow at a rate that allowed Karl to retire in 1898, at the age of 51. Theirs was a life of leisure; they amassed collections of art and manuscripts, furniture and porcelain. And Karl’s siblings — all 11 of them — were just as successful. It was a family of scientists and soldiers, of great thinkers, of judges, of patrons of the arts, and doctors.

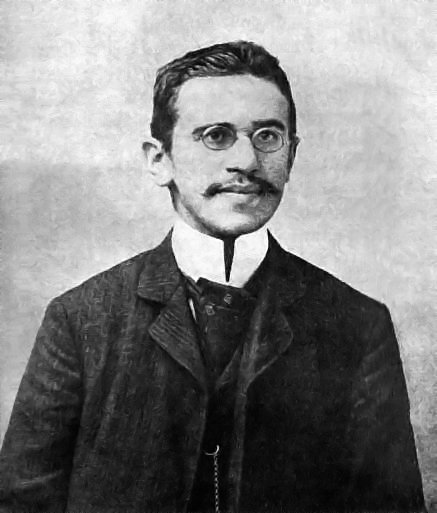

The Wittgenstein home was a hustle and bustle of Viennese culture, and Karl’s children grew up in a home frequented by the likes of Sigmund Freud, Johannes Brahms, and Karl Kraus. It’s also during this time that Wittgenstein read one of the books that would have a lifelong impact on him: Otto Weininger’s 1903 book Sex and Character. While it’s still debated just how much of an impact the book had, it is generally credited for introducing Wittgenstein to the idea that life should be lived in an almost single-minded pursuit of the creation of a work of pure genius. Lofty aspirations, for sure, but hearing some of the names he grew up around, it’s easy to see why he would be so determined to achieve greatness and immortality through his work.

Otto Weininger. Author of the 1903 book, “Sex and Character”

But that good fortune that shaped Karl’s generation did not extend to the next. Our Wittgenstein would leave the family home for Cambridge in 1911, and by then, he had already lived through the deaths of several siblings. His oldest brother, Hans, headed off to America and disappeared in 1902 — the family believed he took his own life. In 1904, the second oldest, Rudy, did the same by drinking a glass of potassium cyanide. As a way of coping, Karl forbid the rest of the family from ever mentioning either of their names again, and it was an order that didn’t just push an already devastated family to the breaking point, it broke them. The relationship between the remaining children and their parents was never the same, and it explained quite a bit about what would happen later.

Even as a young Ludwig Wittgenstein suffered through the loss of his brothers, it’s worth taking a slight aside here to address one of those rumors that sounds so unlikely, so strange, that it has to be false. And in this case… it’s only partially false.

Historians and scholars have long tried to figure out just what drove Hitler’s anti-Semitic madness, and there’s a single mention in Mein Kampf that goes like this: “I did meet one Jewish boy who was treated by all of us with caution, but only because various experiences had led us to doubt his discretion and we did not particularly trust him…”

That’s led to a lot of speculation that Wittgenstein was that boy, as he and Adolf Hitler did — albeit briefly — attend the same school in Linz. It was the 1904-1905 school year, and it’s a rewarding theory. Not only would both go on to be written about in the history books, but it would help make sense of one of the biggest questions of the Holocaust: Why?

Wittenstein and his family would feel the icy grip of the hand of the Third Reich, but that’s for a bit later in the tale. The first strike against this story that Wittgenstein inspired Hitler’s rabid hatred of the Jews is that for three generations, the Wittgensteins had been practicing Roman Catholics, and he didn’t necessarily identify as Jewish — even though baptismal records identified three of his four grandparents as being Jewish before their conversion. And that, too, is going to become important.

And there’s an end to that quote that often gets omitted from the conspiracy theories: “… but neither I nor the others had any thoughts on the matter.” It’s generally believed that it wasn’t until much later that Hitler’s anti-Semetism kicked into high gear, and it’s worth noting that mainstream history has pretty much cleared Wittgenstein of being the root cause of Hitler’s anti-Semitism.

“I shall certainly encourage him. Perhaps he will do great things…”

Wittgenstein’s education was as erratic as his father’s young life had been. He didn’t start in philosophy, in fact, he started out about as far from philosophy as possible. After studying mechanical engineering in Berlin, he switched to aeronautics — and particularly the study of kites — in 1908. That’s also when he headed off to Manchester in England, and his work there led him down the road to mathematics. Finding himself pondering heavy philosophical musings over the foundations of mathematics as a whole, he sought out the mathematician and philosopher Gottlob Frege. It was Frege who recommended that he speak with Bertrand Russell, and it was Russell who saw the potential for “great things” in the young student.

Wittgenstein saw the potential for great things in himself, too, once asking Russell, “will you please tell me whether I am a complete idiot or not?” When Russell asked him why, he responded, “Because, if I am a complete idiot, I shall become an aeronaut; but, if not, I shall become a philosopher.”

Russell instructed him to write a bit of philosophical argument, and he did. Russell read just a single sentence and told him, “No, you must not become an aeronaut.”

Wittgenstein only spent a few years at Cambridge, and a year after meeting Russell, he had spent so much time and effort in the pursuit of logic that Russell declared there was nothing more to teach him. He said, too, that he was difficult — he would often show up in his mentor’s rooms in the middle of the night, pace relentlessly, and declare that when he left, he was going to kill himself. Russell wouldn’t send him away, and they would sit in silence for hours. Finally, Russell asked him if he was pondering the mysteries of logic or of his sins, and responded simply, “Both.”

And he took his deep thoughts very seriously, heading off to Norway for months at a time to simply think without the distractions of campus life. He built himself a wooden hut at the edge of a fjord, and it was there that he laid the groundwork for his beliefs that facts can be shared through what he called “logical forms”.

Wittgenstein left Cambridge in 1913 and it was a year marked by the passing of his father. He quickly gave away his inheritance and by this time, it was the eve of World War One. The following year he voluntarily enlisted in the Austrian Army, and far from being scared, his writing suggests he was looking forward to the war and to the opportunity of getting up close and personal with death. He wrote in one journal “only death gives life its meaning,” and at first, he did spend quite a bit of the war well out of harm’s way. When it came time for him to volunteer for a posting, though, he chose one of the most dangerous: he headed out into no man’s land and manned a lookout post at the front of the Austrian line.

Throughout the war, Wittgenstein continued to write both philosophy and to those he had met and studied with at Cambridge. His admiration of Russell — and Russell’s appreciation of his intellect — perhaps predictably began to go downhill. He was as difficult as he was brilliant, their relationship turned into one of bickering, and a regular theme in Wittgenstein’s journals was one of lament. He was heartbroken at the responses he was getting from his fellow philosophers: even if he survived the war, he wrote, he wondered about the usefulness of his work and worried that no one would understand it — or be able to grasp how important it was.

He wrote constantly during the war, compiling notes for what would eventually be turned into his Tractatus Logico-Philosopicus — or, in translation, his Logical-Philosophical Treatise. It would be the only book he would publish in his lifetime, and scholars that look back over the work in context of what he was going through at the time say it was undoubtedly influenced by the war, and shaped by both his time in relative safety behind the front lines, and in the thick of the fighting.

It was at this time, too, that he read Tolstoy’s The Gospel in Brief, and had something of an epiphany. He read it again and again as wrote his own works on logic, work that was eventually led in the direction of combining ethics, religion, and aesthetics with logic. At the heart of the matter was that all of those topics couldn’t be satisfactorily explained with words, they needed to be shown.

Confusing? Absolutely, and he said so himself when he wrote a friend with this insight: “If only you do not try to utter what is unutterable, then nothing gets lost. But the unutterable will be — unutterably — contained in what has been uttered.”

And that sums up how difficult Wittgenstein can be to read, much less understand. In 1918, he was captured, and spent the remainder of the war in an Italian POW camp; here, too, he kept writing, and when he was released, he published his seminal work. Summing it up briefly is just impossible, but it’s worth nothing that not only did Bertrand Russell write the original introduction for it, but Wittgenstein was fairly disgusted with what he thought was a complete misunderstanding of the text.

At the heart of it is the idea that the world consists of objects. In turn, combinations of objects result in what he described as a state of affairs, and facts were ultimately states of affairs that existed in the real world and could be described via those objects.

Basically.

Wittgenstein had a reason for exploring all of this, and he was trying to construct a system that would allow for a framework with which to divide the world into two areas: “sense and nonsense.” Interestingly, some of the things he defined as “senseless” under his system were things like mathematics and logic, while nonsense was something else completely. That was the idea that something is completely devoid of meaning, and well, he had a lot of time on his hands during the war. Considering that even the professionals in the world of philosophy have trouble describing his work and tracing the leaps and bounds he makes in his logic, we’re just going to leave this one right here.

And that’s exactly what Wittgenstein did, too. After the publication of his work, he was completely convinced that there were simply no more problems left to solve. He quit philosophy and took on a less complicated life, spending nearly a decade traveling around Vienna, taking on odd jobs from gardening to architecture, and occasionally teaching. That particular vocation came to an abrupt and rather brutal end; in one Austrian mountain village, he struck a student so hard he knocked the boy unconscious. His immediate resignation followed, along with a long bout of depression.

Fortunately for the world of philosophy, he was ultimately exposed to the philosophical musings of the Vienna Circle, a group of mathematicians, scientists, and philosophers who met regularly through the 1920s. Thanks to them, he realized that there were still quite a few problems worthy of his attention.

The dawn of World War Two

The realization that there were bigger, better, and deeper philosophical problems that remained unsolved led to Wittgentein’s return to Cambridge in 1929; at the time, he wasn’t the most famous member of his family. That honor went to his brother, Paul, who had always had an innate gift for music, and was known as an outstanding concert pianist. He, too, was in World War One and suffered an injury that should have been devastating: he lost an arm. But even as his brother wandered Vienna looking for a point to his continued existence on Earth, Paul worked with some of the era’s greatest composers to create music for the piano that required only a left hand to play.

As the world slowly inched toward yet another conflict that would engulf the globe, the Austrian brothers found themselves in perhaps the best of places they could be: on the outside. In 1939, Wittgenstein was elected to one of the top positions in Cambridge professorship, and it helped give him something of infinite value: British citizenship. The timing couldn’t have been better.

For years, Hitler had been working on reuniting Germany and Austria; there was a failed coup, a treaty with Italy that promised to protect Austria from German aggression, and even attempts by Mussolini’s Italian troops to interfere with the annexation. It happened anyway, and in 1938 Austria was absorbed into the Third Reich.

That had a devastating impact on the Wittgenstein family. Remember, they had been long-practicing Christians by this time, but what was done in practice and what was written on paper were, in their case, two different things. There was still a record of those three Jewish grandparents, and conversion or no conversion, that meant they were still considered Jewish under the Nuremberg laws dictating racial purity. None of them were able to vote or do seemingly petty actions like sit on a park bench. For all of the siblings, it was dangerous.

Paul in particular — a musical celebrity of 1930s Vienna — was deeply troubled. He was no longer allowed to work in the field of the arts, and more troubling, he was in violation of another law: Section 2 of the Nuremberg Law for Protection of German Blood and German Honor. He wasn’t married, but he was the father of two children — and their mother was German.

Had they been a normal, everyday sort of family, they may have been able to flee without attracting the attention of the Third Reich. But they were one of the wealthiest in Europe, and what followed was a complex bit of legal and financial maneuvering that really didn’t work out well for anyone. In 1939, the two surviving Wittengenstein brothers (brother Kurt had also committed suicide at the end of World War One) appealed their case based on the fact that a single grandparent was the bastard child of a gentile. Along with the appeal went a significant bribe: they handed over most of their fortune to the Nazi regime but in turn, their sisters Hermine and Helene were granted half-breed status and were safe from the relentless march of the Nazi war machine.

It’s undeniable that the Wittgenstein fortune aided the advancement of the Third Reich, and if there ever was a philosophical question that needed debate, it’s that one. What was the true price paid for the safety of the Wittgenstein sisters? Was it worth it? Should they have paid, and would you have? It’s a question that can only be answered by those faced with the impossible question.

It was Paul who was the driving force behind the decision to transfer much of the family’s fortune from a trust in a Swiss bank account to the coffers of the Third Reich; he, the oldest sibling, would be the last to die, and after he made the decision to save them, he would never see any of his siblings again.

For his part during the war, Ludwig Wittgenstein worked as a porter at Guy’s Hospital in London… and here is where we touch on a few of the things that historians and scholars have never truly been able to answer.

The mysteries of Wittgenstein

Wittgenstein’s writings make it clear that there are some unresolved issues simmering away in the background, and it’s a fascinating glimpse into the mind of a man so obsessed with logic. For one, it’s never quite clear whether or not he considered himself Jewish. Occasionally, he did call himself a “Jewish thinker,” while at other times, he condemned what he believed was a misrepresentation of his ancestry.

Similarly, Wittgenstein found himself fighting an almost constant battle with his sexuality. At the time, it wasn’t just taboo to be gay, it was illegal and would have been met with outrage and ostracization at the very least. It’s impossible to tell what kind of effect bearing that sort of burden had on his writing and his philosophy, but it’s also been suggested that he gravitated toward teachings like Freud’s, who suggested people were universally attracted to both sexes. It was an idea that was safely mainstream and may have been a comforting bit of modern thought.

There was another constant and underlying theme throughout not just Wittgenstein’s writings but through the diaries and journals of those who knew him. He spoke often of his thoughts of suicide, told those closest to him about his sense of unrelenting shame and loneliness, and of the possibility of becoming just another one of his siblings to take that final step. His friend David Hume Pisent wrote this heartbreaking glimpse into his psyche: “… he had suffered from terrific loneliness for the past nine years, that he had thought of suicide then, and that he felt ashamed of never daring to kill himself […] he told me that all his life there had hardly been a day in which he had not at one time or another thought of suicide as a possibility.”

Wittgenstein did ultimately die young, but he did not take his own life. For two decades, he struggled to put together another book but, always the perfectionist, he consistently failed in putting together something that would live up to the vision of what he believed it should be. His later works were only published posthumously, and he didn’t live to see the influence he had on 20th-century philosophy.

In 1947, Wittgenstein resigned from his post at Cambridge. Much like he had once retreated to the quiet solitude of the fjords of Norway, he later did the same and headed off to the remote wilds of Connemara in Ireland. The peaceful solitude was not to last. In 1949, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer, and by 1951, he knew he didn’t have long to live. He moved into a home with his doctor and died on April 29, 1951. Reportedly, his last words were, “Tell them I’ve had a wonderful life.”