According to the FBI, the moment when Lucky Luciano rose to the top was “the watershed event in the history of organized crime.” He completely changed and modernized the American Mafia, making sure that whatever turf disputes, power grabs, and other petty squabbles might develop between different crime families did not get in the way of their ultimate goal: making money.

Under his new system governed by the Commission, any major decisions were brought to the table and voted on by the highest-ranking mobsters. By getting the families to work together, he transformed the Mafia from a bunch of gangs constantly fighting with each other into the most powerful crime syndicate in the country.

Early Years

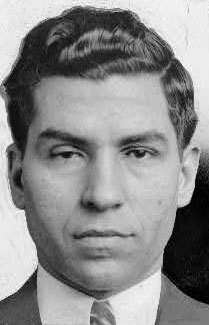

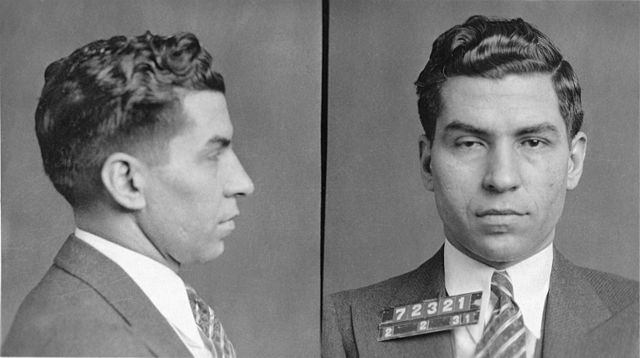

Charles “Lucky” Luciano was born Salvatore Lucania in a small sulfur mining town in Sicily called Lercara Friddi. His date of birth is somewhat disputed – it was either November 11, 1896, or November 24, 1897. His parents were Antonio Lucania and Rosalia Capporelli and he had four other siblings.

The family emigrated to America when Charles was just a nine-year-old bambino and settled in New York City’s Lower East Side. He attended public school until he was 14, at which point he dropped out and found a job as a clerk with a shipping company. However, he realized that there were faster and easier ways to make money, if you were willing to break the law. In fact, Luciano had started a few swindles as soon as he arrived in America. He was first arrested when he was only ten years old for shoplifting. After that, while he was still in school, he started a protection racket for the other Italian and Jewish students. But, allegedly, it was a dice game that convinced him that he wasn’t meant to be just another working stiff, as he walked away with over $240 in winnings, at a time when his job paid him $5 a week.

As a teenager, Luciano hooked up with the Five Points Gang, active mainly in Lower Manhattan, where he met many of his future associates such as Johnny Torrio, Vito Genovese, and Frank Costello. He mainly handled protection rackets and some occasional pimping and drug dealing on the side. During one momentous extortion attempt, Luciano met a Jewish teenager who would later help him revolutionize organized crime – Meyer Lansky, someone we have already covered here at Biographics, in case you want to see his side of the story.

We’re not sure when or why Luciano acquired the nickname “Lucky.” It could have been from his good fortune at the gambling tables, or from his tendency to avoid prison despite being arrested numerous times. It could have been from surviving one particularly harrowing incident when other mobsters beat him up severely and cut his throat, leaving him with permanent scars and a droopy eye, or it could have simply been derived from his last name. As far as his first name was concerned, Luciano started going by Charles instead of Salvatore because he did not want to be called “Sal” or “Sally,” which he felt sounded too feminine.

By the time Prohibition came around in 1920, Luciano was already working for one of the most dangerous men in New York – Joe Masseria aka “Joe the Boss,” who was in charge of one of the most powerful gangs in the city. Around the same time, Lucky also collaborated often with another highly influential mobster – Arnold “The Brain” Rothstein, who acted as a sort of mentor for Luciano and taught him how to run a criminal empire like a successful business.

At the end of the day, making money was what mattered most, but Lucky didn’t really endear himself to some of the old school gangsters due to his close association with Jewish criminals, like Lansky and Rothstein. Many of them didn’t even like working with Italians born outside of Sicily, let alone non-Italians. However, this mentality only made Luciano feel like maybe it was time to make some changes; to let go of the old ways and form a new and modern criminal enterprise. And those who weren’t willing to change…well, they had to go, too.

The Commission Is Born

We’ve talked about this important chapter of criminal history a few times in our bios about Bugsy Siegel, Meyer Lansky, and Frank Costello, so we’ll just give a cliff notes version this time. Basically, during the late 1920s, a violent power struggle known as the Castellammarese War emerged between two New York factions – one of them was led by the aforementioned Joe “the Boss” Masseria, the other by Salvatore Maranzano.

While these two were fighting to establish themselves as the head honcho, a lot of their underlings were growing dissatisfied with their role within the organization. Many of them understood that, as long as there was a capo di tutti capi, one boss above all others, there would always be multiple people vying for that spot which, in turn, meant that the gangs would be focused on fighting each other instead of other activities that actually made them money. Therefore, in May 1929, they held a landmark summit in Atlantic City, where they discussed the future of organized crime, eventually leading to the formation of the National Crime Syndicate, a loose confederation of gangs from all over the country working together or, at the very least, not actively working against each other.

Everyone who was anyone attended that conference. Enoch “Nucky” Johnson acted as host and represented New Jersey; Al Capone and his men represented Chicago; Santo Trafficante Sr. represented Florida; there were also the Philly Mob and the Detroit Purple Gang. New York, of course, had the most representatives, from all the Italian crime families, plus the Jewish and Irish mobs. Two notable absentees were Masseria and Maranzano. They would never have ceded power willingly so, instead, it was decided that both of them had to take a dirt nap.

The first one to go was Joe the Boss, in a hit that was planned by Lucky Luciano himself. As Masseria’s lieutenant, he reached a secret deal with Maranzano to betray his former boss in exchange for his rackets and a position as Maranzano’s new second-in-command. Masseria was gunned down in a restaurant on April 15, 1931, with mobsters like Vito Genovese, Bugsy Siegel, and Albert Anastasia rumored to have been the triggermen.

Now Salvatore Maranzano was the new boss of bosses and, although his reign at the top only lasted for a few months, it was long enough to have an impact. Most notably, he organized New York’s Italian gangs into the Five Families, a well-known structure that still exists today, albeit under different names. He also developed the ranking system within the family with a boss who had an underboss, several lieutenants called caporegimes, and then soldiers. He even gave his organization a fancy new name – La Cosa Nostra.

Anyway, by September, Maranzano realized that Luciano was too ambitious and too dangerous to keep around, so he wanted him six feet under. Lucky knew this, so he planned his own hit against Maranzano. Again, we don’t know who the shooters were, but a four-man squad burst into Maranzano’s office on September 10 and gunned him down. Several more hits were carried out in the weeks that followed on Maranzano’s associates who would not have taken kindly to the reforms that Luciano and his colleagues had in mind.

With both Masseria and Maranzano dead, Luciano could have proclaimed himself the new boss of bosses, but he didn’t…not exactly. Instead, he and several other mob bosses formed the Commission in 1931, a sort of governing body for the American Mafia. All important matters and conflicts were brought to the table for discussion where every boss got a vote, although the boss of the most powerful family was always considered the de facto leader which, in this case, was obviously Luciano. With this new world order established, it was time for Luciano and his cohorts to concentrate on profitable enterprises.

Luciano VS Dewey

Even while he was still working under Joe Masseria, Luciano ran one of the most lucrative bootlegging businesses in New York. But now, as the head of his own crime family, he became involved with gambling, extortion, loansharking, prostitution, drug dealing, and bookmaking, not to mention all the extra income he gained by controlling interests in construction companies, trucking companies, garbage collectors, garment stores, the docks, and all other sorts of union jobs. He made Vito Genovese his underboss, while Frank Costello served as his consigliere. Meyer Lansky also held an important position within the Commission and always had Luciano’s ear but he could never attain a rank higher than “associate” since he was not a full-blooded Italian.

Alongside guys like Costello and Bugsy Siegel, Lucky also helped form the public image of the stereotypical Mafia boss that you see in every mob movie, the one who always dressed in nice suits and fancy silk shirts, and went out to eat at expensive restaurants, then went to party in trendy nightclubs with famous celebrities. Luciano enjoyed being a public figure, but this had downsides because it also garnered the wrong kind of attention, like that from prosecutor and future Governor of New York Thomas Dewey.

Dewey proclaimed Lucky Luciano to be “Public Enemy Number One” and made it his new mission to bring him to justice. This was not the prosecutor’s first rodeo. He had previously put bootlegger Waxey Gordon behind bars and was on the verge of doing the same to Jewish mobster Dutch Schultz before Schultz’s murder in 1935. Little did Dewey know at the time, he was the reason for Schultz’s death and that Luciano indirectly saved Dewey’s life.

Dutch Schultz had wanted to kill Dewey and, as per the new rules, he asked permission from the Commission. They refused, since killing a prosecutor would have brought way too much heat on them, but Schultz intended to ignore them and do it anyway. That was when Luciano and the other mob bosses voted to have Schultz whacked for going against the Commission.

Now that Dewey had Luciano in his sights, he focused on his thriving prostitution ring by organizing raids on countless brothels. He brought in police officers outside of the vice squad and had them wait on the streets, ready to strike, only telling them the locations of the raids minutes in advance. This was done in order to foil any attempts to warn the mob and the strategy paid off as Dewey made hundreds of arrests.

Also worth mentioning was his Assistant District Attorney, Eunice Carter, one of the first Black female lawyers in New York’s history. She was instrumental in building the case against Luciano by gaining the trust of many of the prostitutes and madams that were caught up in Dewey’s raids. Ultimately, she got multiple women to testify that Luciano was the boss in charge of the organization. Carter backed up their statements by following the money trail which always led back to Luciano. By March, Dewey and Carter had built a strong enough case against Luciano that they were ready to proceed with the arrest.

Mugshot of Italian-American mobster Charles Luciano

In late March 1936, Luciano was staying at the Waldorf Towers under the name Charles Ross when he got a tip that detectives were on their way to bust him. He quickly left the hotel, drove to Philadelphia where he borrowed some money and a new car, then drove to Cleveland, Ohio, where he caught a train to Hot Springs, Arkansas, a place where he hoped he could lay low until the heat died down.

Luciano’s plan didn’t work. He was recognized and arrested in early April, prompting an extradition battle to New York where he had been indicted on over 60 counts of compulsory prostitution aka pimping. A few weeks later, Lucky was in New York and, by May, his trial had begun.

The case against him was strong. Dewey painted an accurate picture of Luciano’s influence and his role within the mob by presenting his connections to numerous other criminals, his numerous arrests, and the testimonies gathered by Eunice Carter. Then Dewey focused on Luciano’s inability to explain the source of his wealth since it was clear that Lucky lived the lavish lifestyle of a millionaire even though he only declared a yearly income of $22,500.

It seemed that, after dozens of arrests with no convictions, Luciano’s luck had finally run out. On June 8, 1936, he and eight co-defendants were all found guilty on 62 counts each. Despite attempted bribes, threats, and even attacks on his life, Dewey had triumphed and Lucky Luciano was sentenced to 30-to-50 years in prison.

Life Behind Bars

Although he was now behind bars, it was all business as usual. Luciano still ran his criminal empire, with Frank Costello and Vito Genovese carrying out his orders on the outside. However, once he exhausted his appeals and it became evident that he would not be getting out anytime soon, Luciano ceded power to Costello and named him the new acting boss of the family, to the great displeasure of Genovese who wanted that position for himself…but more on that later.

That’s how life went on for the next few years until Luciano saw a new opportunity for freedom, provided to him by an unexpected source – World War II.

Once the United States had joined the war, there was a growing concern over enemy spies, especially after the SS Normandie, a French ocean liner, caught fire in February 1942, and sank while being refitted in the New York harbor. Although the exact motive for the capsize has never been established, the American government feared that it was the work of a saboteur. When their own efforts to weed out possible spies among New York’s dockworkers did not yield substantial results, the government began thinking laterally and turned to an organization that had already been controlling the docks for decades – the mob.

Thus began Operation Underworld, a cooperative effort between the US Government and the Mafia to foil sabotage attempts, prevent labor disputes during wartime, help undercover agents and limit black market theft.

The first mobster approached by Naval Intelligence officers was Joseph Lanza, a mid-level gangster with the Luciano family who ran the Fulton Fish Market. At first, the government just wanted help so their agents could go undercover and keep tabs on workers with Mussolini sympathies. However, Lanza recommended that they ask his boss for assistance, since Lucky still controlled the docks, even though he had been in jail for six years by that point.

Luciano agreed to help and he was moved to a more comfortable prison as thanks, although it is still a matter of heavy debate whether Operation Underworld was actually of any use or not. Some rumors even say that the mob were the ones who set fire to the Normandie in the first place. Anyway, once the war was over, Luciano filed an appeal for clemency on the basis of his cooperation. Thomas Dewey, the same man who put him behind bars, was now Governor of New York, and he actually agreed to commute Luciano’s sentence in recognition of his wartime aid, although he still got the last laugh.

In early 1946, after almost a decade in prison, Lucky was once again a free man, but his release came with a heavy caveat – he would be deported to Italy and never allowed to return to the United States again. On February 9, Luciano was escorted by immigration agents and New York police officers aboard a freighter called the Laura Keene. Meyer Lansky claims to have bribed the guards to arrange a little farewell party for Luciano – champagne, food, women were brought aboard the ship, as Luciano, Lansky, Costello, and a few others had one final get-together to reminisce about the good ol’ days. According to the police, this never happened, and their account is supported by an FBI report from an agent who was there undercover, so who knows if it actually happened or not? One thing was certain – on February 10, Lucky Luciano set sail for Italy and he would never set foot on American soil ever again.

Lucky Goes to Cuba

Just because Lucky couldn’t physically be in New York did not mean that he was ready to give up the criminal empire that he had built there. However, Italy was a bit too far away from the action so, after his deportation, he made plans to relocate to Cuba. Meyer Lansky already had multiple gambling operations in the country and the mob had pegged it as a great new investment opportunity, not just for gambling, but also for prostitution and drug dealing. They would have needed someone to stay in Cuba to look after their interests anyway so, if everything went according to plan, it could have been like Luciano never left.

To that end, the mob scheduled another summit like the one in Atlantic City back in 1929. This one took place in December 1946, at the Hotel Nacional in Havana, although getting there proved a little problematic for Luciano since he didn’t want to tip off the US Government as to his whereabouts. He had to leave Italy a few months earlier and make several trips through South America to lose his trail before he finally arrived at his destination incognito.

The main talking points at the Havana Conference included the status of the drug trade and a final decision regarding the fate of Bugsy Siegel, who had gotten on everyone’s bad side after bungling the development of the mob’s first hotel in Las Vegas. Luciano also weighed in on the rivalry that was brewing between his two main subordinates, Frank Costello and Vito Genovese. Even though Lucky named Costello as the acting boss of his family, it was becoming increasingly clear that Genovese coveted that position and that he intended to get it, one way or another. According to a semi-biographical account dictated years later by Luciano himself, Vito approached him in private and suggested that Lucky proclaim himself as the “Boss of Bosses,” but purely as a symbolic title, while Vito himself would actually run the criminal syndicate back in New York. This is what Luciano replied:

“There is no ‘Boss of Bosses.’ I turned it down in front of everybody. If I ever change my mind, I will take the title. But it won’t be up to you. Right now you work for me and I ain’t in the mood to retire. Don’t you ever let me hear this again, or I’ll lose my temper”.

After the speech, Lucky also met with Genovese in private just to make it abundantly clear that he was still the boss. Apparently, Vito broke a few ribs by “falling down the stairs” and had to stay behind to recuperate before returning to New York.

Unfortunately for Luciano, his own stay in Cuba was cut short once the American authorities found out that he was there. In February 1947, they demanded that the Cuban government arrest and deport Luciano. At first, Cuba refused, but then the United States stopped all shipments of legal narcotics to the country until they complied. This was all the “persuasion” needed and the Cuban police arrested Lucky the very next day and deported him by the end of the month. It seemed that his plans to continue serving as the mob boss from Cuba had failed and there had been rumors that it was actually Vito Genovese who tipped off the American authorities in the first place.

Final Years in Italy

Back in Italy, Luciano was immediately arrested and spent a few weeks in jail in Palermo before being released. He would be kept under closer surveillance from then on but, of course, this hardly acted as a deterrent for Lucky, who remained involved in the drug trade, often serving as the connection between the Sicilian and American mobs. He was arrested several times in Italy, but each time he was released without charges. It seemed that his luck when it came to avoiding prison sentences had returned, but his freedom to travel was being increasingly restricted. In 1949, he was labeled a “crime threat” and banned from entering Rome. In 1952, the Italian police took away his passport. By 1954, Luciano was not even allowed to leave Naples without permission. He had to stay at home every night, he had to check in with the police once a week and he was barred from entering “dens of iniquity” such as racetracks and liquor stores. Despite all of these restrictions, Luciano was still described in the press as “one of the chief exponents of the international underworld and the moving force of all unlawful traffic, especially of narcotics, between Italy and the United States.”

The authorities might have proven powerless to stop Luciano, but he also had enemies on the other side of the law and they posed a far greater threat. Specifically, Vito Genovese, whose ambition to become the new don had never wavered – he was simply biding his time, coiled like a snake waiting for the right opportunity to strike.

That opportunity came in 1957. Genovese felt confident enough that he put out a hit on Frank Costello. It failed, as Costello was only injured, but Costello got the message loud & clear and he retired, enabling Vito to take charge of the family, which he renamed the Genovese family after himself as another sign that Lucky was out of the picture and that it was his show now. Meanwhile, Vito’s main ally, Carlo Gambino, also put out a hit on Albert Anastasia, another boss of one of the Five Families. This one was more successful and Gambino became the new head of the family, which he also renamed after himself.

While this was happening, there was little that Luciano could do from thousands of miles away but read about it in the papers. Costello and Anastasia had been two of his strongest allies and, with them gone, his influence decreased significantly. His one consolation was that Genovese only got to enjoy his new position of power for a couple of years before he was arrested and imprisoned, thus paving the way for Carlo Gambino to become the new boss of the American Mafia.

As far as Luciano was concerned, he remained involved in the business, but his role steadily decreased as time went by. He thought about telling his life story so it could be turned into a movie, but this never panned out. Instead, all of the notes he dictated were used for a book, which came out a decade-and-a-half later.

On January 26, 1962, Lucky Luciano was at the Naples airport waiting for the arrival of a movie producer when he suffered a heart attack and died, aged 64. After a funeral service in Italy, his family obtained permission from the American government to bring his body and bury it in New York. His impact on American organized crime might have been greater than any other person and it is still evident today.