He was a king whose reign outshone even the sun. Louis XIV of France was one of history’s major monarchs, ruling with absolute power for nearly three-quarters of a century. In Europe, the length of his rule is unmatched. Globally, his reputation is nearly unparalleled. Under the Sun King’s watch, France experienced Le Grand Siècle, or the Great Century, a period Voltaire called “one of the great centuries of civilization.” Art, culture, and fashion all flourished; Versailles was built, power centralized. Along its borders, France expanded, becoming the undisputed focal point of European life.

But was there more to the reign of Louis XIV than a shiny French utopia? Born into a time of civil strife, Louis was a product of war. He fought constantly, against his neighbors, against Protestants, against the world. And even as his armies racked up victories, they sowed the seeds of Le Grand Siècle’s bitter end. One of the great, towering figures of history, this is the complex life of France’s brightest royal star.

The Sun Rises

It was a dark and stormy night. And, no, we’re not cribbing lines from Snoopy’s typewriter, that is literally how the story of Louis XIV starts!

Anyway, it was a dark and stormy night, and Louis XIII was cursing his awful luck. Thanks to the inclement weather, the king of France had become trapped at the apartments of his wife, Anne of Austria.

And this was a problem because Louis XIII and Anne detested one another. Not in an ‘arguing about the dishes’ kinda way, this was hatred burning so bright it could be seen from space. As a result, the royal couple hadn’t produced a single heir during their long marriage.

That all changed that stormy night.

Trapped together, Louis XIII and Anne evidently put aside their differences. By the time the sun rose the next morning, Anne was pregnant with the future king. At least, that’s the official version. The unofficial one is that Anne may have been canoodling with her confidant, Cardinal Jules Mazarin, and the “dark and stormy night” story was concocted to save everyone embarrassment.

Whatever the truth, nine months later, on September 5, 1638, the future Sun King was born. Almost from the moment he emerged, Louis XIV was being force-fed evidence of his own importance.

Anne was a strict Catholic, who told her son he was chosen by God to lead France, even giving him the nickname Dieudonné, “Given by God”. When Louis’ brother Philippe was born two years later, she made the boy wear dresses and referred to him as “my little girl,” as if to remove any threat he might pose to Louis’s claim on the throne.

Not that Louis’s childhood was all pampered.

For one thing, Anne’s belief in God’s plan for her son made her somewhat careless as a mother. The future king nearly drowned as a toddler because Anne wasn’t paying attention. For another thing, Louis had just been born into mid-17th Century France.

And mid-17th Century France was a society devouring itself.

Rather than a unified nation, 1640’s France was badly fractured, with many provinces under de facto control of not the crown, but powerful nobles. When Louis XIII died in 1643, Anne and Cardinal Mazarin set up a regency to rule in Louis XIV’s name and tried to reign in the power of these nobles.

Unfortunately, those nobles would rather burn the world than let their power decrease.

In 1648, France exploded into an ugly civil war known as the Fronde, right in the middle of a separate war with Spain.

At the Fronde’s height, a Parisian mob stormed the royal palace, baying for Louis’s blood.

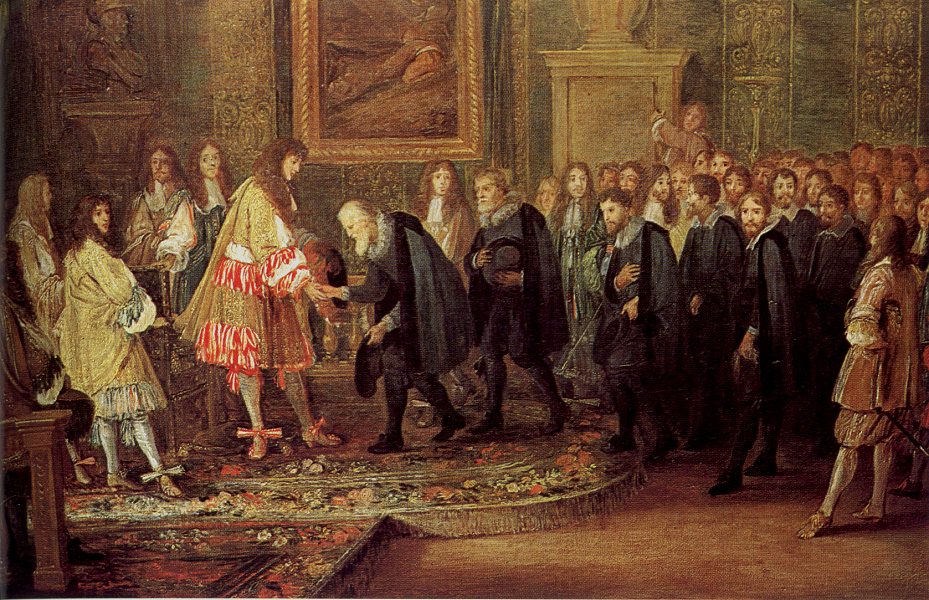

Luckily, this particular mob was less interested in recreational decapitation than most Parisian mobs, and they left Louis alive after the boy pretended to be asleep. Still, the incident badly scarred him. For the rest of his life, Louis would regard the French capital with utmost loathing. By 1654, Marazin had won the Fronde for the crown. That same summer, the cardinal had 15-year old Louis crowned king in a ceremony attended by almost no-one.

Not that Mazarin needed the crowds. He was the real power behind the teenage king, and everyone already knew it.

But Mazarin wasn’t the cartoon villain you’re probably expecting.

Although he kept Louis XIV on a short leash, he also taught him the dark arts of politics. How to manipulate people, how to convince them your great idea was their great idea. Gifts that would serve the young king well. But Mazarin also gave the boy a gift he was less happy with. When Louis decided to marry Mazarin’s niece, Mazarin was all like “Uh, no. You’re marrying this Spanish princess to symbolically mark the end of this stupid war we’ve been fighting. Deal with it.”

And that was how, in 1660, Louis XIV came to marry Maria Theresa of Spain, a woman he hated only marginally less than his father had hated Anne.

But if this seems an ignoble start for the king who would become the most celebrated in French history, just know that it’s not going to last. Less than 9 months after his unwanted marriage, Louis would be stepping out from behind Mazarin’s shadow, and into the blinding sunlight.

Daybreak

On March 9, 1661, Cardinal Mazarin departed for the great Catholic party in the sky. The very next day, Louis XIV made a surprise announcement. He would not be replacing Cardinal Mazarin with a new chief minister.

Instead, he would rule France as an absolute monarch.

This was one ballsy move even in 17th Century France. The last absolute monarch had been Henry IV, whose rule had ended over 50 years ago. This was like Helmut Kohl casually announcing in 1995 that Germany was going to revert to a military dictatorship. How the hell would such a thing even be possible?

But Louis was adamant. He’d been put on Earth by God to rule France.

And, by God, was he gonna rule the heck outta France.

To show he was serious, Louis had paintings commissioned of himself as Roman emperors and Greek Gods. He declared himself Roi-Soleil – the Sun King. This caused some rumblings among the nobles, rumblings Louis would’ve been ill-advised to ignore. Including the Fronde, the nobles had started 11 civil wars in the last four decades. To paraphrase the old meme, one did not simply declare oneself above the nobles without a fight.

But Louis didn’t want a fight. No, his plans for conquering the nobles involved using the subtle arts Mazarin had taught him.

But first, he needed a place to do it.

Construction on the Palace of Versailles began in 1661, using as its core an old royal hunting lodge some 20km outside of Paris. Remember how we said Louis hated Paris? Well, Versailles was an expression of that hate. 20km away may not sound like much, but when your main form of transport is a horse-drawn carriage, it sure feels longer.

And that was kinda the point. Louis wanted to separate himself from the capital, but he also wanted to separate his court from anywhere the nobles might have allies. If he could lure them away from their power bases… if he could dazzle them with opulence… if he could occupy their brains completely with courtly life…

Well, then they might not have enough time left for civil war.

At first, Louis’ clever plan didn’t quite pan out.

Nobles declared “Versailles is a mistress without merit” – a way of saying that it looked like a building site and there was nothing to do. But the Sun King didn’t waver in his course. Although the court moved around endlessly in these days, it kept coming back to Versailles.

And, when it did, Louis ensured there was enough to occupy even the most Machiavellian mind.

There were hunting trips. Gambling. Parties of such extravagance that engravings were made and sent as ‘how to’ guides to the other courts of Europe. Even the clothing worn was time-consuming. Louis decreed it must be French made, at enormous cost, and that only certain people could wear certain colors.

Naturally, this created competition among the nobles. Elites who might otherwise have been discussing a big-budget sequel to the Fronde were instead scheming against one another for the right to wear blue with gold.

And Louis backed all this weird new etiquette with action.

Nobles who played by the rules found themselves getting showered with gold – not literally, that’d be horrific – while those who refused were suddenly staring at empty coffers. Just as an exclusive new club can attract members purely because it is exclusive, the Sun King’s court pulled in the nobles purely because being there demonstrated your nobility.

You can see this clearest in the weird rituals undertaken each day.

Come morning, all the nobles were expected to watch Louis get dressed, with some even helping the king into his shirt. But rather than punishment, the act of dressing the king was a reward; an expression of a noble’s closeness to power.

And closeness to power meant money.

Before long, Louis had all the nobles where he wanted them: fighting over objectively ridiculous rituals while he floated serenely above it all, like some ancient sun god. It was the first big step on the road to Le Grand Siècle.

It wouldn’t be the last.

Summer Love

While the great parties of Versailles may have been a way of dazzling the nobles, like waving a lightbulb in front of a bunch of moths wearing tiny powdered wigs, that didn’t mean the Sun King was all calculation and no fun.

One of the nicknames for this era was The Reign of Love. And it wasn’t meant in the sense of the love of a man for a fine Cuban cigar.

Throughout his reign, the Sun King had so many affairs he practically made infidelity into a spectator sport.

There was Louise de La Vallière, maid of honor to Louis’ sister-in-law, Henrietta of England, who Louis started pretending to see as cover for one of his other affairs, and wound up sleeping with anyway. But the king didn’t just stop with sleeping with her! Louise was elevated to the position of king’s official mistress – which has to be the most French concept we’ve ever heard – and kept in luxury at Versailles.

Until her downfall, that is. Eventually, Louise was deposed and replaced by the Marquise de Montespan, a woman of vast temper and a wit so cutting she caused abject terror. But not for Louis, who set her up in her own private apartments adjoining his own so he could have sex with her three times a day; a habit that resulted in them having seven children.

Louise, meanwhile, was packed off to a convent to live out the rest of her life in isolation. When she eventually died, the King could barely manage a shrug of indifference.

But while the Marquise became Louis’s main lover, she wasn’t the only one.

That Henrietta of England we mentioned earlier, wife of Louis’ brother Philippe? Well, Louis totally seduced her too. Not that Philippe likely minded, as he was himself sneaking off for nighttime trysts with buff man’s man, the Chevalier de Lorraine.

In fact, this whole attitude of free love permeated the Sun King’s court. Everyone was sleeping with everyone in a nonstop orgy of… err… orgies.

But if that sounds kinda fun to you, just know it was only for a tiny elite.

Most of the regular folks of France were starving. Those working on the Versailles building site were barely making enough to afford food. Those who complained were thrown in jail. So yeah, the Great Century was great for most people in the same way that the Great Depression was great for the average human, i.e. not at all.

Still, it’s not like Louis was only playing mind games and making love.

Despite having an adultery schedule that would leave even Boris with an exhausted Johnson, Louis found time to work for 8 hours a day on kingly stuff, every day. Along with Finance Minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, he overhauled the economy, building a network of canals, roads, and ports in a handful of years that transformed French life.

Louis was even slightly progressive for his time, promoting ministers from the Bourgeoisie at the expense of the nobles, much to those same nobles’ horror. But the Sun King wouldn’t be respected today if he’d just spent his time building roads and dropping his pants.

No, getting to the top of the European royals in the 17th Century meant one thing, and one thing only.

It meant going to war.

The Noonday Sun

The issue with going to war is that, even in an absolute monarchy, your subjects tend not to take very kindly to being told to die on a battlefield without good reason. With the economy expanding, Finance Minister Colbert was eager to swallow up some new territory, ideally the Spanish Netherlands – what we’d today call Belgium and Luxembourg.

But while that was a good enough reason for Louis and Colbert, it wasn’t for the public.

So the Sun King set about finding a reason.

In the mid-1660s, Louis announced that his marriage to the Spanish Maria Theresa meant the Spanish Netherlands should – for complicated dynastic reasons – belong to him. It was clearly the French King grasping at straws, but it was also enough. In May of 1667, Louis launched the War of Devolution, which should perhaps be known as The Unprovoked Invasion of Belgium.

Although the French made great gains, international pressure from England forced them to mostly withdraw, leaving the Spanish Netherlands in Spanish hands.

But despite this setback, the war wasn’t a failure.

For one thing, the early French victories, and the fact Louis had withdrawn under diplomatic pressure rather than in the face of great losses, seriously boosted his popularity. For another, it cemented in many people’s minds the idea that France had some sort of claim to the Spanish Netherlands.

Now all Louis had to do was wait until the time was right, and he could try again.

That right time came sooner than anyone was expecting.

In 1670, Louis signed a secret treaty with Charles II of England, playing on the fact they were both Catholics to win over his former rival.

Then, in 1672, he launched his re-invasion.

The new French attack on the Netherlands was so successful it’s still known in Dutch history as Rampjaar, or “the year of disaster”.

It didn’t help that, in 1674, the British joined in on Louis’s side, leaving their former Dutch allies out to dry.

It wasn’t until the Dutch leader, William of Orange, married Charles II’s niece that England abandoned Louis and the war ended.

By that time, though, Louis had gotten what he wanted.

The gains made by the French armies in the Franco-Dutch War effectively created the modern French-Belgian border. Louis snatched towns and cities from the Spanish Netherlands that would remain French until today.

Although he hadn’t delivered the hammer blow against the Dutch he’d been hoping for, Louis returned from the war at the height of his powers.

In Paris, he was given the nickname “the Great”. People lined up to sing his praises.

Finally, it was here: the zenith Louis had imagined when he became an absolute monarch all those years ago. The Sun King at his noonday height. But the king had forgotten what happens to the sun after it reaches its highest point.

It always sets.

Louis XIV didn’t know it yet, but the sun of his reign was already dipping towards the horizon.

From here on out, it would be all downhill.

The Setting Sun

From one perspective, the early 1680s should’ve been a time of triumph for Louis.

In 1682, building work on Versailles was finally completed, allowing the Sun King to permanently station his court in the most opulent building on Earth. From another perspective, though, the course of the decade had already been set. Its well already poisoned.

The trouble started in 1679.

That year, a police investigation revealed many members of the aristocracy had been visiting fortune tellers – an illegal act – using potions, taking part in black mass, and trying to poison their rivals. Scores upon scores of Versailles regulars were implicated. Most damaging for the king, his mistress, the Marquise de Montespan, was revealed to have used love potions on him.

The fallout of the Affair of the Poisons was felt across French society.

At court, the Sun King quickly changed tack, ditching the party lifestyle and imposing sobriety and piety on his nobles, and replacing the Marquise de Montespan with the sober and pious Mme de Maintenon. Of course, this was just for the public and, behind the scenes, everyone kept right on gambling, drinking, and having affairs.

But it left a nasty taste in the mouth, one that poisoned the public against France’s elites.

But if the Affair of the Poisons was a catastrophe Louis couldn’t predict, the next disaster was of his own making. Way, way back in 1598, Henry IV had signed the Edict of Nantes, granting rights to the Protestants of France. Known as the Huguenots, they numbered around one million, most of them skilled artisans. In the eighty-plus years since they’d integrated into French society.

But when the extremely Catholic Louis looked at them, he didn’t see a group with a valuable skillset.

He saw outsiders. Invaders. A swarm of good for nothings. So the Sun King decided to do something. In 1685, Louis revoked the Edict of Nantes, replacing it with the Edict of Fontainebleau.

Suddenly, tolerance was out. Persecution and murder was in.

Huguenot churches were destroyed, schools closed. Protestants were sent into internal exile. Those who refused were executed. It was a cruel, senseless policy. It was also a spectacular own goal. As news of Louis’ decrees spread, outrage swept the Protestant nations.

Refuge was offered for the Huguenots, in Prussia, in parts of the Holy Roman Empire, in England.

It’s actually from these fleeing Huguenots that English gets the word “refugee”, and that’s not all England got. Of the tens of thousands of refugees that came to England, almost all of them carried some vital skill. France lost so many of its best craftspeople that entire industries suffered. It’s thought today that the Edict of Fontainebleau set sectors of the economy back decades.

But from Louis’s perspective, it had an even worse effect.

Over in the Netherlands, the Protestant William of Orange was getting jumpy. Revoking the Edict of Nantes might be a warning sign Louis was going to invade again. To top it off, England had just coronated the staunchly Catholic James II. Without England onside in any future war, William knew the Netherlands was lost.

So he decided to force England onto his side.

In November, 1688, William of Orange set sail at the head of a huge invasion force. If you’ve ever heard that 1066 was the last time Britain was successfully conquered, that’s only because William of Orange’s victory was so quick that everyone forgets it.

Within weeks of William’s landing at Torbay, James had been captured and the entire country turned pro-Orange. The thing is, Louis could’ve almost certainly stopped the Glorious Revolution. Had he done so, he would’ve gained a Catholic ally in James II, and a chance to crush the Protestant Dutch.

But Louis was simply too arrogant to believe God wasn’t on his side. That England’s Catholics wouldn’t rise up and overthrow William.

By the time he realized what a geopolitical screw up he’d just committed, it was too late.

Without a drop of blood being spilled, William and his wife Mary were made joint monarchs of England in January 1689. And, just like that, Catholicism in Britain went into terminal decline.

And, just like that, Louis’ fortunes went into terminal decline, too.

Twilight of the Sun King

On July 1, 1690, a huge French force gathered in Ireland to try and restore James II to the English throne.

Instead, they were defeated in the bloody, bitter Battle of the Boyne, a Protestant victory that remains hugely controversial in Ireland. But by then, Louis already had other troubles on his mind.

By 1690, France was embroiled in the War of the Grand Alliance.

The War of the Grand Alliance – also known as the Nine Years’ War – is one of those olde timey conflicts that’s super complicated to explain without us launching a whole new channel named Warographics to walk us all through it. Since we don’t have time for that, just know it was in part triggered by the impending death of Carlos II of Spain.

A Habsburg, Carlos was so inbred he was incapable of siring an heir. That meant who would rule Spain next was an open question. So Louis tried to make the answer to that question “France”, resulting in a long, bloody, inconclusive war that only petered out in 1697 when Europe was exhausted. And the worst part?

Everyone was about to do it all over again.

Three years after the War of the Grand Alliance ended, Carlos died for real, and Louis declared his own grandson Philip the new king of Spain. To be fair to Louis, he knew grabbing the Spanish throne would lead to another European meltdown. But he felt he had no choice. What if one of his enemies grabbed it instead? So, with a heavy heart, Louis pressed the Doomsday button on Le Grand Siècle.

The thirteen years of fighting that followed were less the Great Century, and more the Crappy Decade.

France’s forces were decimated. Territory lost. At the same time that France was suffering on the world stage, the Sun King was suffering in private, too. As the war progressed, Louis’s son, two of his grandsons, his great-grandson, and his great-granddaughter all passed away. In public, the energy of the Sun King’s early years faded away, replaced by a melancholy that seemed to turn everything a dull, midwinter gray.

Remarkably, this misery actually won Louis public support. It was said the king was carrying the nation’s entire grief in this time of war. When the War of the Spanish Succession finally came to a close in 1714, the Sun King had almost faded away. While a late surge by the French had allowed them to keep Louis’s grandson on the Spanish throne, it still felt like a failure.

Philip had been excluded from the line of French succession, meaning Louis’s dream of a unified France and Spain could not be realized.

Not that Louis had much longer left to dream anyway.

Louis XIV fell deathly ill at Versailles in August 1715. On his deathbed, the Sun King famously confessed to his surviving great-grandson – the future Louis XV – that he’d gone to war for vanity’s sake, and that his grandson shouldn’t be like him.

Then, with his final breaths, he declared “I depart, but the state will always remain!”

The Sun King died on September 1, 1715. At the moment the sunset on his reign, Louis XIV had been on the throne for 72 years and 110 days. When he first became king, France had been a divided state, the French monarchy a second-tier power.

Now, as dusk finally fell, it was across a France at the height of its powers. Paris was the global center of fashion, art, and culture.

But if Louis thought in his last moments that the story ended here, he was wrong.

Over the next 74 years, the system of government Louis had set up would ossify into the Ancien Regime. In 1789 it was this regime that was overthrown in the greatest European upheaval of all: the French Revolution.

But that’s for another video. For now, it’s simply enough for us to bid farewell to Louis XIV, to perhaps the greatest French king to have ever lived.

He may have made mistakes, he may have been an autocrat. But the Sun King’s life is destined to forever shine throughout history, visible even into the far distant future.

For a king as egotistical as Louis XIV, that’s exactly what he would’ve wanted.

Sources:

Britannica bio: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Louis-XIV-king-of-France

History bio: https://www.history.com/topics/france/louis-xiv

Good BBC Radio bio showing a different side to Louis (two episodes): https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b05wyhns

BBC Documentary on Versailles: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ZtCFI3uwoM

Louis at Versailles: http://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/history/great-characters/louis-xiv#from-royal-residences-to-the-palace-of-versailles

The Sun King’s many affairs: http://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/history/key-dates/louis-xiv-and-his-women

The Fronde: https://www.britannica.com/event/The-Fronde

Franco-Dutch War: https://www.britannica.com/event/Dutch-War

Affair of the Poisons: https://www.historyextra.com/period/stuart/scandal-conspiracy-and-the-affair-of-the-poisons-inside-the-court-of-louis-xiv/

Battle of the Boyne: https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-the-Boyne

War of the Grand Alliance: https://www.britannica.com/event/War-of-the-Grand-Alliance

The Huguenots: https://www.history.com/topics/france/huguenots

Were Anne and Mazarin having an affair? https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/3618846/Was-the-Sun-King-the-kings-son.html