The perfect crime…a favorite topic among mystery writers and television showrunners, who are always coming up with new and clever ways to commit cunning, albeit fictional murders. It is not so much a concern for real criminals. As far as most of them go, a perfect crime is any one that they can get away with.

There is, perhaps, one notable exception to this – Leopold and Loeb, two well-off, educated students who killed a young boy in 1924 because they wanted to commit “the perfect crime.”

It wasn’t murder that excited the duo. It was getting away with murder. As far as they were concerned, that was where the challenge lay. A challenge that, as we all know by now, they failed…miserably because Leopold and Loeb were not the criminal masterminds they thought they were. Sure, they had high intellects, but the superiority they liked to flaunt in everyone’s faces was all in their heads.

A smart person does not necessarily equal a successful criminal, and the pathetic reality was that Leopold and Loeb only committed a string of petty vandalism acts and once they moved up to a serious crime, they were caught almost immediately. But due to a sensational trial, nationwide media coverage, and a controversial verdict, this murder was among the select few to be heralded as the “crime of the century,” ensuring everlasting notoriety for Leopold and Loeb.

Making Two Murderers

Nathan Freudenthal Leopold Jr. was born on November 19, 1904, in Chicago, Illinois, the son of Florence and Nathan Leopold Sr. His father was a German Jewish immigrant who amassed a nice little fortune for himself by running a freight and transport company, so no expense was spared regarding young Nathan’s education.

All of that money seemed to be well invested since Nathan Leopold proved to be a child prodigy. There are numerous examples of his impressive precociousness, but a bit of skepticism is advised. Most of them come from Leopold’s own autobiography and, let’s face it, not many people admit to being morons; especially not someone like Nathan Leopold who had a gigantic superiority complex and thought that he was better than everyone else.

Half a year after Leopold’s birth, another wealthy Chicago family welcomed their new son into the world. Richard Albert Loeb was born on June 11, 1905, to Anna Henrietta and Albert Henry Loeb. Like his future partner-in-crime, Richard had a privileged upbringing, as his father was not only a successful lawyer, but also a senior executive at Sears. However, his dark side started manifesting from an early age as Loeb enjoyed committing petty crimes, mainly thievery, and was only emboldened when he did not face any serious consequences for his actions, even when he was caught. A few trips to the woodshed might have saved a lot of people a lot of grief.

The two young men grew up in the same affluent area of Chicago but didn’t really have more than a casual acquaintance with each other. This changed in 1920 when both boys skipped a few classes and were sent to the University of Chicago. Leopold was 15 years old while Loeb was 14. Both had similar backgrounds and interests, so a friendship naturally developed between the two. However, their partnership almost never got off the ground because the following year Loeb transferred to the University of Michigan. There, he took to heavy drinking and card playing, and his grades started slipping. The words “wasted potential” were quietly hovering above his head, but ultimately, Loeb barely managed to graduate from the University of Michigan aged 17, becoming the youngest graduate in school history. In 1923, Loeb went back to the University of Chicago to continue studying for his master’s degree, and there he rekindled his friendship with Nathan Leopold, who was doing the same thing.

Eventually, the two became lovers. They had personalities that complemented each other very well. Loeb was more outgoing, handsome, and charismatic. He provided the socially awkward Leopold with thrills and experiences that he could never accrue on his own. Meanwhile, the more intellectual Leopold taught his companion about his life philosophies, which Loeb ultimately adopted as his own. Specifically, Leopold became fascinated with the works of Friedrich Nietzsche, particularly the concept of the Übermensch, or Superman. Put simply, a superman was superior to all the average joes around him and was not bound by the same societal norms and ethics. As Leopold himself wrote in a letter: “A superman … is, on account of certain superior qualities inherent in him, exempted from the ordinary laws which govern men. He is not liable for anything he may do.”

It won’t surprise you to discover that Nathan Leopold considered himself one of these supermen due to his intellect. And wouldn’t you know it, it turned out that Loeb was one of them, too…what were the chances of that? Already, they had the makings of their own little Justice League, so what did they decide to do with all these gifts that they had been apparently blessed with? Why, commit vandalism, of course. Richard Loeb resumed his life of petty crime and brought Leopold into the mix, often using sexual favors to persuade him to join in on the fun. Even so, it didn’t really take a lot of convincing since, in their minds, they were completely justified and unaccountable for their actions. They started out by committing burglaries, stealing cars, smashing windows, but nobody seemed to care. They then moved up to starting fires, but, once again, evaded any kind of consequences. Clearly, they were the greatest criminal masterminds that the world had ever seen, so it was time to up their game again and carry out something that would get the whole city talking.

Folie à Deux

Leopold and Loeb began obsessing over committing the “perfect crime.” They spent months going over their plan. Ultimately, they decided that they were not only going to murder someone but that they were going to make it look like a kidnapping, complete with a ransom demand and a series of complex instructions to throw investigators off their trail.

First, the victim – who were they going to kill? Leopold and Loeb decided that they needed someone who came from a rich family so that they could pay the ransom and, ideally, somebody who trusted them because it would make the kidnapping go much smoother. They thought about targeting a member of their own families, but, eventually, concluded that they should not pick someone so close to them. Ultimately, they left the identity of their victim to chance – they knew that they would kidnap a boy from their neighborhood, who came from a rich family and went to one of the local schools, but did not know who it would be until the day of the crime. A quick little side note here: American film producer Armand Deutsch always claimed later in life that he had been the intended target, but that a dentist appointment saved his life on that fateful day, since the family chauffeur picked him up to drive him to the dentist’s office.

On May 21, 1924, it was time for Leopold and Loeb to set their plan in motion. They spent most of the afternoon driving a rental car around the Kenwood area of Chicago, looking for their unfortunate victim. They spotted several potential targets and rejected them all for various reasons. At around 5 o’clock, they were about ready to call it quits for the day when the perfect opportunity presented itself to them. It was 14-year-old Bobby Franks, walking home from school. All the circumstances seemed perfect: Bobby was alone, his family was rich enough to pay the ransom, and he knew Richard Loeb, so his guard was down when the car quietly pulled up alongside him.

Loeb and Leopold offered to give Bobby a ride and once the young boy was in the car, his fate was sealed. The two criminals had already established that they should do the killing as fast and as soon as possible so, when Bobby Franks looked out the window unsuspectingly, he was hit in the head with a chisel. His killer struck him several times without hesitation and without mercy, but Bobby still held on. The blows caused multiple gashes that spurted blood everywhere inside the car. The killer decided to switch tactics, so he forced a piece of cloth down Bobby’s throat, keeping his mouth shut until the young boy suffocated and all signs of life left his body. The deed was done, although who exactly was the doer remains a bit of a mystery since, during the trial, both Leopold and Loeb claimed they were driving the car while the other one actually committed the murder.

Bobby Franks was dead, but that was just the first step of the plan. Now came part two: getting rid of the body. The killers had their dumpsite already picked out – a marshy culvert near Wolf Lake, about 25 miles out of the city. It was an area that Nathan Leopold knew well as he often visited it to do a spot of birdwatching. They drove around town until it was dark, even stopping for a hot dog at one point despite having a dead body in the backseat. Already, the arrogance of the two killers was evident, as, in their minds, nothing could possibly go wrong.

Once night came along, the duo took a remote dirt road to Wolf Lake. They stripped Bobby Franks naked and dumped his body in the culvert. Afterward, they went to Loeb’s house, disposing of the murder weapon somewhere along the way. At home, they burned all of their bloodstained clothes and then got to work cleaning the rental car.

The Kidnapping

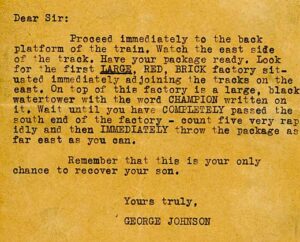

At the Franks household, Bobby’s parents, Jacob and Flora, had begun to panic when their son did not show up for dinner. None of his friends or siblings knew where he was, and a search of his school already revealed that he did not get trapped inside or anything of the sort. Jacob Franks called a friend of his, a lawyer named Samuel Ettelson, for assistance. While the two of them were out, Flora Franks received a phone call from a man claiming to be George Johnson, who told her that her son had been kidnapped and to expect instructions in the morning.

In reality, this was Leopold and Loeb enacting the third part of their so-called master plan: the kidnapping. They thought that adding this component to their crime would not only increase the thrill but also obscure their true motive from the police, not to mention giving them a little extra spending money, since they intended to collect the ransom. They made the initial call while returning from Wolf Lake, at which point they also mailed the ransom note, which arrived at the Franks’ house the following morning. It was fairly boilerplate as far as ransom demands go: don’t alert the authorities, prepare $10,000 in old, unmarked bills, and wait for another call. If the Franks obeyed these instructions, then Bobby would be returned to them unharmed. Little did Jacob and Flora know that it was already too late to save their son.

While Jacob Franks was getting the money, Samuel Ettelson alerted the Chicago PD that Bobby Franks had been kidnapped. This was all supposed to be hush-hush, but a journalist found out about it, probably after being tipped off by a source inside the police department. Like any good newshound, he was up-to-date with all the goings-on in the city, so he also heard about the body of a boy that had recently been found near Wolf Lake which was being treated as a possible drowning victim. He may have been the first to connect the dots between the two events, and he told the police, who then told Jacob Franks.

Franks reacted exactly like you would expect a heartbroken father to react. It couldn’t be Bobby, he said. The description of the body did not match him. It wouldn’t make any sense for the kidnapper to kill him…These were all the justifications of a desperate man who was clinging on to hope that his son was still alive but while Jacob Franks waited to receive a new call from the kidnapper, his brother-in-law went to view the body.

At around 1 pm the following day, “George Johnson” phoned again. Samuel Ettelson answered the call, and the kidnapper told him to get in the cab that would arrive shortly and go to a certain drugstore where they would receive another call. Ettelson then passed the phone to Jacob Franks, who received the same instructions. However, in all the excitement, both men immediately forgot the address of the drugstore so, when the taxi arrived, neither one knew exactly where to go, and neither did the cabbie. Not that it would matter for long, because right before leaving, Jacob Franks received another phone call. This one, however, wasn’t from the kidnapper. It was much worse than that…it was from his brother-in-law, who called to tell him that the dead boy found near Wolf Lake was his son.

The Investigation

Leopold and Loeb were starting to realize that this whole “murder” business wasn’t as easy as they thought. The killing was far more violent and chaotic than they had expected. The kidnapping didn’t go anywhere because Bobby Franks’s body was discovered almost immediately. And, as you will soon find out, the disposal was the worst one of all and the one that would ultimately sink the two “alleged” master criminals.

Unsurprisingly, the murder of Bobby Franks immediately became the biggest topic of discussion in Chicago, and the state’s attorney Robert Crowe took personal charge of the investigation, smelling a nice, big promotion at the end of it. The first lead came from the ransom note. Investigators determined that it had been written on an Underwood typewriter by an intelligent and educated man. This would have been the perfect occasion to try to lead the authorities astray by fudging the English a bit and making it sound like the kidnapper was an ordinary criminal, but Leopold and Loeb’s egos would not have allowed that. They could never refuse the opportunity to show off their intellects, even when it went against their own interests, so, of course, Leopold typed the ransom note in perfect English, using long, fancy words that proudly showed off his higher education and legal expertise.

That was Leopold’s folly, but Loeb was no better. He was so arrogant and confident that he thought it would be fun to investigate his own crime with some of his fraternity brothers, including a reporter for the Daily News. Everyone knew about the failed kidnapping plot, so the 19-year-old Loeb and a few other students tried to track down the drugstore where Jacob Franks was supposed to go, to see if they could find any clues. At one point, the reporter even asked Loeb if he knew the victim, to which Loeb smiled and said: “If I were going to murder anybody, I would murder just such a cocky little son of a bitch as Bobby Franks.”

It’s like they couldn’t help themselves. Leopold and Loeb were two egomaniacs who could not resist the temptation to show off how superior they were to everyone else and to insert themselves into the investigation. They thought they were so distinct and special, and it is almost amusing how much of a cliché they really were.

On the other side of the law, the police already had Nathan Leopold’s name, since he had been spotted around Wolf Lake several times by the game warden. They interviewed him, but because he was an established ornithologist, he had a valid excuse to travel to Wolf Lake on birdwatching expeditions. Plus, he came from a rich and respected family, and nobody thought that someone like him could commit such a heinous act. Not yet, anyway…

The police bought Leopold’s story for the time being, but eight days after the murder, they caught their biggest break in the case. Next to Bobby Franks’s body, they had found a pair of glasses, which had fallen out of Leopold’s pocket while carrying the body. The prescription was very common, so the police didn’t think that anything would come of it, but checked them out anyway, and they hit pay dirt. The hinges on the glasses were very distinct, and only one place in Chicago had them. They only sold three pairs like that – one of them was to Nathan Leopold.

It was time to take off the kid gloves, but the police still didn’t want Leopold to think they suspected him. They even booked a room at the LaSalle Hotel for their interview, so they could have a little discretion, away from the prying eyes of the press. What Leopold did not know was that Richard Loeb was being interviewed in the room next to him.

For the most part, the two of them stuck to the same story – they spent most of the day together, driving around town in Leopold’s car, eating, drinking, and bird watching. At night, they picked up two girls and drove around town some more, and ended the night by driving Leopold’s aunt and uncle home.

Now that’s a lot of driving, so it’s fair to say that it was an integral part of their alibi. Except that when the police questioned the family chauffeur, he said that he had worked on Nathan Leopold’s car all day that day and that it stayed in the garage until he left home for the evening. Just like that, the web of lies had been exposed. When presented with the facts, Loeb was the first to crack and told the police everything just ten days after the would-be “perfect crime” occurred. He ended his confession with an attempt to pass the blame onto Leopold. He said:

“I just want to say that I offer no excuse, but that I am fully convinced that neither the idea nor the act would have occurred to me had it not been for the suggestion and stimulus of Leopold. Furthermore, I do not believe that I would have been capable of having killed Franks.”

The Trial of the Century

Suffice it to say that the arrest and trial of Leopold and Loeb caused a bit of a palaver, becoming one of the first few examples to be referred to as the “trial of the century” in the papers. The families of Leopold and Loeb hired one of the best lawyers in the country – Clarence Darrow – the same man who would defend teacher John Scopes in the Scopes Monkey Trial a year later.

Leopold and Loeb had already pleaded guilty on Darrow’s recommendation. This way, the trial turned into a sentencing hearing, and the lawyer only had to argue in front of a judge instead of a jury. His one job was to prevent his clients from having a date with the hangman’s noose. He did this by bringing in several psychiatrists (or alienists, as they were called back then) to testify to the mental state of the accused. He also brought up their age, admission of guilt, neglect, and even sexual abuse Leopold might have suffered at the hands of his governess when he was a kid. Anything to create some kind of mitigating circumstances for Leopold and Loeb. Darrow ended the hearing with a two-hour-long speech described as masterful and the finest of his career…which we will now reproduce for you in its entirety. Ahem…just kidding. Basically, it was a plea for mercy, an attack on capital punishment itself, and an argument that the sentence should be reformatory, not retributory. Whatever he said, it persuaded the judge, who sentenced Leopold and Loeb to life in prison for the murder, plus 99 years for the kidnapping.

That was the end of the criminal careers of Leopold and Loeb. The two of them stayed friends on the inside and even started a school for prisoners in 1932 at Statesville Penitentiary. However, Loeb was killed in 1936 by his cellmate, James E. Day, who cut him with a straight razor over 50 times, possibly after Loeb propositioned him for sex.

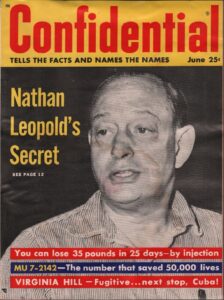

Nathan Leopold was actually paroled in 1958, after 33 years in prison, seemingly a reformed man. He no longer thought of himself as a “Superman,” instead calling himself a “humble, little person.” He moved to Puerto Rico in search of obscurity, where he continued studying birds, got his master’s degree, found a job, and even got married. He died of a heart attack in 1971.