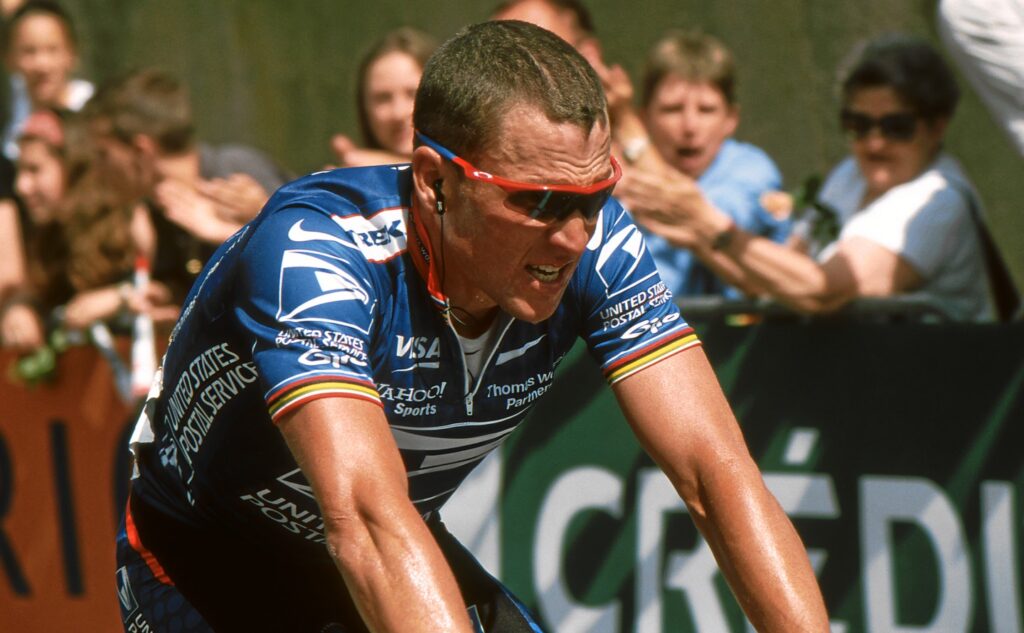

He is the world’s most famous cyclist, dominating his sport like no one before or since. Yet his reputation has been forever tarnished by a scandal that tore at the very fabric of professional cycling, pitting the sports elite against each other. The doping scandal, however, was just one in a series of mountain-like obstacles that have confronted Lance Armstrong. The story of how he has overcome them is an inspirational story of perseverance, tenacity, and self-belief. In this week’s Biographics, we explore the tumultuous life of Lance Armstrong.

Credit: de:Benutzer:Hase – Self-photographed, CC BY-SA 3.0

The Formative Years

Lance Edward Armstrong was born as Lance Gunderson in Plano, Texas on September 18, 1971. His mother, Linda, was just seventeen and a high school dropout, while his biological father, Eddie Gunderson, was a route manager for The Dallas Morning News. The marriage was an unhappy one, with Eddie proving to be abusive and neglectful. They divorced when Lance was two years old.

Before long, Linda had remarried. Lance’s step-father was a travelling salesman named Terry Armstrong. Armstrong was a stern, distant man who never really bonded with Lance during his formative years. Terry’s job kept him away from the home a lot. When he was home, he proved to be a harsh disciplinarian who would beat Lance with a paddle for any incursion. Not surprisingly, the boy looked forward to his step-father’s work trips, when it was just he and his mother at home.

As the years progressed, the family’s finances improved and they moved to better neighborhoods. They ended up in Richardson, where Linda signed up young Lance for swimming lessons. She also bought him a bicycle.

Young Lance was an active, inquisitive child. He often got into fights, with one scuffle getting him kicked off the school bus, after which he rode his bicycle to school. He had a love of competitive sports, though he never clicked with football, the dominant sport in Texas. Instead, he became passionate about running and swimming.

Young Lance had an abundance of energy. His favorite TV show was The Six Million Dollar Man, and he loved nothing better than to run around the neighbourhood pretending to be the bionic man as he chanted the words of the show’s theme song . . . ‘better, stronger, faster.’

From Richardson, the Armstrong’s moved to Plano, Texas, where Linda’s new job as a telecommunications company secretary enabled them to buy their first house. It was here that they lived through the bulk of Lance’s schooling. He attended the Armstrong Middle School, Williams High and Plano East High.

Linda bought her son his first serious bike when he was seven. It was a Schwinn Mag Scrambler BMX racing bike. The bike, along with a helmet and safety gear, cost three times more than Linda was hoping to spend, but she saw the value in getting her son involved in an outdoor sport. Lance rode his Scrambler until he was 13, when his mother bought him a Mercier road bike.

Lance’s competitive career began at age twelve when he competed in the Plano Swim Club Champs. He achieved some success, but a year in he saw a poster for a triathlon and decided to switch to the three-discipline event. His first triathlon was the Iron Kids, which he won handily.

With his step-father often absent from the home, Lance lacked a strong male role model during his formative years. That role was filled in his early teens by Chris MacCurdy, his Plano swimming coach. MacCurdy trained Armstrong right through Middle School and High School and encouraged him to compete on a national level and even to set his sights on the Olympics.

Another man who took an interest in the teenage Lance was the owner of the local bike shop, Jim Hoyt. He gave the Armstrong’s discounts on equipment and Lance managed to earn some money riding for events that were sponsored by Hoyt.

When he was 14, Lance competed and won his first duathlon, consisting of swimming and running. The prize was a one-hundred-dollar pair of Avia running shoes. However, when the shoes arrived in the mail, they didn’t fit. The sales rep who came to the Armstrong home with a replacement pair, Scott Eder, ended up taking Lance under his wing and taking him to workouts and competitions.

Eder took Lance to the Cooper Institute in Dallas when the boy was 16. The researchers there tested his V02 Max, which came out at 79.5 percent. It was the highest they had ever seen. This meant that Lance had an incredible ability to make use of every breath of oxygen that came into his body. The testing also showed that he had the highest lactic acid threshold they had ever come across.

Through his formative years, Lance had found a knack for getting himself into trouble. He and his mates would sneak into neighbor’s houses and steal beer from the fridge. On one occasion he and another boy glued the mailbox of a man who they had argued with. The police came calling when he stole an ‘Armstrong Street’ sign as an ornament for his room.

When he was sixteen, however, his mother told him that she was planning on leaving his stepfather. She urged Lance to stop getting into trouble as she wouldn’t be able to handle to stress that it would bring. Lance responded, channelling all of his energy into his sporting events.

Creating an Athlete

Lance and Linda now spent most weekends together, traveling to 10k running events and triathlons that he competed in. During the week, Lance spent many hours going on long rides with his cycling buddies. Linda helped her son to seek out sponsors who would supply such things as shoes and jerseys. Every single sponsor received a handwritten letter of thanks from Lance.

There are four competitive cycling categories. All riders start out at Cat Four. For Lance this meant Tuesday night criterion rides at the local Bike Mart. It wasn’t long before he moved up to Cat Three, where he found himself training with a couple of Cat One guys.

When he was sixteen, Lance was riding his Mercier racing bike along the Dallas countryside when he was apparently run off the road by a truck driver. A furious Lance cursed at the driver from the asphalt. This caused the man to see red, and he stopped his truck and got out in a rage. Lance jumped to his feet and took off, but the man trashed his bike. Before he left, Lance managed to record his number plate. Linda proceeded to sue the man and win. She used the money to buy her son a new Raleigh bike with racing wheels.

Lance’s new bike didn’t last for long. Not long after receiving it, he was hit by an SUV while running a yellow light. He was thrown over the handlebars and onto the hood of the SUV. He was lucky to get away alive, especially since he wasn’t wearing a helmet. He turned up at the hospital with a twisted foot, some scrapes, and a concussion.

With his foot laced with stitches and in a heavy brace, Lance’s doctor told him to do nothing for the next three weeks. But there was just one problem – he had a triathlon race in six days. The doctor told him to forget about it. Instead, he got rid of the brace on the second day, cut out the stitches himself with a nail clipper, and turned up on the starting line that Saturday. He led the swim and the ride, eventually coming in third. When he heard about it, the doctor who had treated him could hardly believe it.

By the time of his final year in high school in 1989, Lance was a national-level cycling competitor. He had qualified to train with the junior national team at Colorado in preparation for the World Junior Championships. However, he faced some serious pushback from his school.

Throughout his high school years, Lance had missed a lot of school due to his traveling around the countryside to compete. The school, however, had viewed the absences as being on par with playing hooky. The told him that he did not have leave to go to Colorado, or, indeed, to follow on to Moscow to compete in the World Champs. The fact that cycling wasn’t even recognized as a sport by Texas high schools at the time factored into their decision-making.

More was to come. Despite his working overtime to meet the requirement, a meeting was called where Lance and his mother were told that he would not be able to graduate with his class that year. They didn’t care that he was an emerging elite athlete with an unprecedented opportunity to advance his career. To them, Lance was a slacker.

Linda soon got her son into a private school that would let him graduate. The teachers at his new school, Bending Oaks Academy, were happy to work around Lance’s schedule to help him to complete his schooling.

Armstrong’s fierce competitiveness brought him to the attention of the coach of the US national cycling team, Chris Carmichael. Carmichael later noted . . .

He was so aggressive that he’d either tear the field apart and win or pull everyone after him so they’d blow by him at the end.

Lance qualified for and competed in the Junior World Champs in Moscow in 1989. This was to prove to be his breakout year. He got more attention than others because of his aggressive racing style. He broke away from the main group in the first lap, riding in the front peloton, and was right up there until the final thrust, where stronger riders pushed ahead of him.

His performance at Moscow marked Armstrong as the most exciting new cyclist on the world stage.

He showed himself to be an aggressive competitor with the ability to focus like a laser beam on achieving his goals. He was supremely confident, which was easy to read as arrogance. He also had no interest in riding as part of a team. He didn’t want anything to detract from his desire to cross the finish line first.

Armstrong competed at his first Olympics at Barcelona in 1992. He later recalled that he ‘rode miserably as an inexperienced hothead’ and finished a disappointing 14th in the road race. His performance, however, was enough to bring him to the attention of the director of a professional team that was sponsored by Motorola. After the Games, Lance was signed onto the team, which officially made him a professional athlete.

Under the Motorola banner, Lance traveled to Europe in order to compete in a series of road races. His first race was in San Sebastian, Spain and he came in dead last. The crowd jeered at him when he crossed the line 30 minutes after the winner.

Armstrong was deflated after this race and considered flying back to the United States. But, his coach convinced him to prove to himself and his teammates that he was no quitter and he stayed on. From race to race, he got better. He came second in the Zurich Championships, finally telling himself that he was capable of doing this.

One of Lance’s biggest challenges with Motorola was to learn to work as part of a cycling team. He would quickly get frustrated with the other riders in his peloton, yelling at them to, “Pull or get out of the way!” Competitors would try to frustrate him on purpose, encouraging him to take the lead and wear himself out early.

After just twelve months as a professional cyclist, Lance had already earned the nickname “the King.” At the 1993 UCI Track Cycling World Championships in Oslo, Norway, the Motorola team decided that he was ready to take the title, and they would work with him to win the race. Rather than rushing to the lead, he stayed in the peloton until the second-to-last lap, as instructed. Then he attacked to take the lead and stay there. Crossing the line well ahead of the competition, he bowed to the crowd, blew kisses, and, in what was to become his trademark, pointed to the sky.

Armstrong was now the world champion, but to truly be the best he knew he had to win the Tour de France. In 1995, he won a stage of the world’s greatest race, dedicating the win to a teammate who had died during a crash in the race. In August 1996 he signed a two-year contract with the Cofidis Cycling team in France.

Cancer

In 1996, Lance noticed that his right testicle was becoming swollen. This was followed by a dull ache and then a lack of energy. This affected his performance at the ’96 Olympics and he had a disappointing finish. In his memoirs, he recalled that he felt like he was ’dragging a manhole cover’ during the road race.

In October after returning from the Olympics, Armstrong was diagnosed with testicular cancer. He had put off seeing a doctor, but when he began coughing up blood he knew he had to act. The news rocked Armstrong and his support team. He was twenty-five, an elite athlete and he had stage three testicular cancer that had spread to his brain, lungs, and abdomen.

His chances of survival were estimated to be below 50 percent. It looked pretty likely that he would never race again, despite recently signing a $2.5 million contract with Cofidis. His team’s lawyers decided that they would not provide insurance cover during his treatment as the condition had not been advised at the time of the signing of the contract.

There were sponsors, however, who did not abandon Armstrong during his time of need. Oakley even offered for him to be covered under their health plan.

Armstrong took on the cancer challenge with the same fierce determination that had made him a world champion. He underwent a program of intense chemotherapy treatment. He sought out and began treatment with a very caustic chemo cocktail known as VIP, which was less damaging on the lungs than conventional treatment. This choice probably saved his cycling career.

Throughout his chemo treatment, Armstrong competed sporadically. Understandably, he did not do well, but he was keeping himself in the game. The final chemo treatment took place on December 13th, 1996. In February 1997, his doctors were able to confirm that his cancer was in full remission.

Tour De France

Armstrong returned to competitive cycling at the beginning of 1998. His contract with Cofidis had been canceled in 1997 and he had signed on with the US Postal Service cycling team. He moved to Europe with the team to train for the Tour De France.

Armstrong was now being recognized as the posterchild for cancer survivor, receiving many awards and titles. Throughout 1998, he built successes one upon another as he steadily improved his placings. That year he also married his fiancée, Kristin Richard. The marriage would last five years and produce three children.

Armstrong won his first Tour De France in 1999. He won four stages and had learned to work well with his teammates. He finished the race 7 minutes and 37 seconds ahead of the second-place finisher. In a post-win interview, he proclaimed, ‘If you get a second chance at life for something, go all the way’.

In 2000, Armstrong came back to France determined to defend his title. The race turned out to be a battle between him and Jan Ullrich, who had competed the previous year. This rivalry was to continue for the next five years. Armstrong crossed the finish line six minutes ahead of Ullrich to become a two-time champ.

Armstrong dominated the cycling world in the early 2000’s. His consecutive run of Tour De France victories stretched to an unprecedented seven in row, stretching from 1999 to 2005. Following his July 24th, 2005 win he announced his retirement from competitive cycling.

Allegations of Cheating

In the wake of his stunning 1999 Tour De France victory, there were allegations that Armstrong must have been involved in either drug-taking or blood doping. In early 2000, under the auspices of the Nike corporation, he created a documentary-style advertisement entitled Body in order to answer the detractors. The film focused on his steely will to win and showed footage of him undergoing drug tests. The voice-over narration was done by Armstrong himself. At one point he says . . .

Everybody wants to know what I’m on. What am I on? I’m on my bike, busting my ass six hours a day. What are you on?

When results came through that he had tested positive for a minute amount of corticosteroid after the ’99 Tour De France, many people doubled down on their accusations. But the amounts in his body were so minute that they were not enough to fail the test. Since then he has never failed a drug test.

There has however been quite a lot of circumstantial evidence. In 2004, a book was published called L.A. Confidential which claimed that Armstrong had been using performance-enhancing drugs. It quoted from Steve Swart, a former Motorola team-mate who claimed that all the team members were using as far back as 1995. When allegations made in the book were reprinted in the British newspaper The Sunday Times, Armstrong sued them, leading to an out-of-court settlement.

In June of 2012, the US Anti-Doping Agency brought allegations against Armstrong of running a huge doping ring among his teammates during his competitive career. They were armed with testimony from a number of former teammates. Their goal was to have him banned from any sport that followed the World Anti-Doping Code. Lance did not appeal the ban.

Armstrong continued to vehemently deny the allegations of doping until 2013. Then, in a bombshell interview with Oprah Winfrey, he admitted that he had used performance-enhancing drugs for all of his Tour De France wins. He claimed to have used erythropoietin and human growth hormone and to have engaged in blood doping.

The reaction was one of outrage. Parties began lining up to sue Armstrong, including teammates he had called liars and parties that he had won libel suits against. The US Justice Department sued him for millions of dollars that the US Postal Service had spent on sponsorship. Many of these suits are ongoing.

The World Cycling Governing Body issued a lifetime ban to Armstrong. He still competes in amateur events, however. Today, he owns a coffee shop in Austin, Texas and a bike shop called ‘Mellow Johnny’s’. Though he will never shake the reputation as the world’s greatest cycling cheat, he has rebuilt a life for himself that allows him to indulge his cycling passion and his competitive nature as an amateur athlete.

Livestrong

Following his successful cancer treatment, Armstrong started the Lance Armstrong Foundation. It began with a fundraising race to raise money for cancer research. One of the most successful initiatives of the foundation was the production, in 2004, of a silicone band imprinted with the word LIVESTRONG. Over 80 million of these bracelets have been sold worldwide.