If you open a Bible to Matthew 2:16-18, you’ll encounter one of the most notorious stories in any religion. Suspicious of a prophesy about a new king, Herod the Great tricks the Magi into telling him where baby Jesus was born, then sends his soldiers to massacre every child under the age of two in Bethlehem. It’s a scene of shocking cruelty, one that has ensured King Herod’s name is still synonymous with evil today.

But what if we told you there was more to Herod’s story?

Born in southern Palestine in 73 BC, Herod was a man at the center of events that shaped history. He was there when Rome transformed from a republic to an empire. He consorted with Julius Caesar, befriended Mark Antony, and submitted to the rule of Augustus. As king of Judea, he rebuilt the Second Temple, saved the Olympic Games from bankruptcy, and projected Jewish power across the world. Yet he died an unloved tyrant, hated by his people, his name forever stained with the blood of the innocent. This is the story of how one great man became the tyrant king of history.

The Last Days of Judea

When Herod was born in 73 BC, it was a great time to be from a Jewish family.

Roughly a hundred years before, a group of priests known as the Maccabees had rebelled against the Seleucid Empire and turned Jerusalem into an independent city state. For the first time in a long time, the Jews were beholden to no-one.

That “no-one” included the superpower of the era, the mighty Roman Republic, with whose blessing Judea kept its independence.

Unfortunately for Herod, his family’s Jewish roots weren’t as clear cut as he might have liked.

The son of a wealthy, ambitious man known as Antipater, Herod was by birth part Edomite, part Arab. Although his father’s family had been practicing Jews for a century, they were still seen as outsiders in Judea, a stigma that kept the family from power.

But Herod’s pop Antipater was nothing if not ambitious. And there was no way he was going to let his murky origins halt his family’s rise.

The year Herod turned six, Antipater got his chance.

In 67 BC, Alexandra-Salome, the Queen of Judea, died. Unfortunately, she died without leaving a clear line of succession, and her two sons elected to take their claims to the battlefield.

And so began the first in a series of wars that are gonna wrack Judea for the rest of this video.

On one side was the Queen’s son Hyrcanus II. On the other was Hyrcanus’s brother Aristobulus. Spoiler alert: you only need to remember Hyrcanus.

As the war got underway, Hyrcanus came to Herod’s dad to beg for his support. Antipater agreed, but not because he thought Hyrcanus was in the right.

In their short meeting, Antipater realized just how weak and easy to manipulate Hyrcanus was. And what could be better than having a weak, manipulatable king on the throne who owes you a favor?

By 63 BC, the war was moving decisively in Hyrcanus’s favor.

Besieged in the Temple, Aristobulus was fast running out of options. Faced with the imminent collapse of his claim to the throne, Aristobulus decided to roll everything on a crazy gamble.

At the time, the Roman general Pompey was riding around the eastern Mediterranean, conquering everything in sight. So Aristobulus bunged the general a massive bribe to invade Judea on his behalf.

This would turn out to be a hilariously bad move.

When word arrived, Pompey moved his army on Jerusalem. There he assessed the situation, came to the conclusion Aristobulus was going to lose, pocketed Aristobulus’s money and sided with Hyrcanus to defeat him!

Amusing as this was, it was also a major historical turning point.

In the wake of Aristobulus’s defeat, Pompey annexed large parts of once-independent Judea. He then installed the victorious Hyrcanus on the throne as a Roman client king.

Just like that, the era of an independent Jewish state came to a close. In its place began an era of a Jerusalem under the heel of Rome.

Not everyone was upset by this.

For Herod’s dad, Antipater, Pompey’s intervention was like winning the lottery. With Hyrcanus II in charge, Antipater began happily cooperating with the new Roman authorities and establishing himself as the real power behind the throne.

Not that the population of Judea made this easy. In 57 BC, an anti-Roman uprising forced Hyrcanus and Antipater to call the Roman Army back to save their butts.

This time, Mark Antony answered the call.

Like Pompey before him, Mark Antony subdued Jerusalem with ease. In the aftermath of the campaign, he was introduced to Antipater’s now 16-year old son.

Despite being ten years older than Herod, Mark Antony hit it off with the boy. Pretty soon, they were firm friends.

It was a friendship that would soon make Herod the most-powerful man in Judea.

The Winds of Change

There’s a peculiar curse that afflicts small states on the doorsteps of superpowers. Each time the winds of change ripple through the corridors of power, the smaller state has to hunker down in case everything it holds dear is blown away.

In Rome, in 53 BC, a hurricane was brewing.

For seven years, the Republic had been under the sway of something called the First Triumvirate, a collection of three great men, all hoping to one day become undisputed ruler.

The first was Pompey, the old benefactor of Antipater and Hyrcanus II. The second was a man known as Crassus.

The third was Julius Caesar.

In May, 53 BC, Crassus died, ending the First Triumvirate. With the third part of their trio gone, it could only be so long before Caesar and Pompey turned on one another.

In January, 49 BC, they did.

The civil war that ripped through the Roman Republic smashed apart old certainties everywhere.

In Judea, a presumably panicked Antipater and Hyrcanus were forced to choose who to throw their support behind: Pompey, the man who had given them power; or Caesar, the man Mark Antony now fought for?

In the end, Antipater went for Caesar. It could have been a catastrophe, the first step along a path that ended with the victorious Pompey having Antipater’s entire family crucified.

Instead, it became the making of them.

On August 9, 48 BC, Caesar annihilated Pompey’s army at the Battle of Pharsalus. Broken, Pompey ran, only to be assassinated later that year.

In the aftermath, you better believe ol’ Julius didn’t forget who his friends were.

In 47 BC, Antipater was rewarded for ditching Pompey by being made procurator (or financial governor) of Judea.

Not only that, but he was given Roman citizenship, something he was able to pass onto his son. And Antipater had big plans for his new, citizen son.

That same year, 47 BC, Antipater pulled some strings and had the 26 year old Herod made Governor of Galilee.

This was the first time the ancient world got a good look at the sort of ruler Herod would be. The results were as shocking as you might expect.

As Governor of Galilee, Herod’s first task was to take care of some partisans who were hiding out in caves, trying to overthrow the Roman-backed state and calling themselves the “new Maccabees”.

Everyone expected Herod to wage a conventional war. Instead, the new governor located the cave system the rebels were hiding in, and sent in soldiers with orders to massacre everyone.

It was a day of bloodshed so great that it triggered riots in Jerusalem. Herod was actually hauled before the religious authorities and threatened with death for his actions.

But Herod stood his ground. Before the highest priests of Judaism, he asserted his right as governor to deal with rebels as he saw fit, including wholesale murder.

Despite his brutality, Herod was let off free, escaping the death penalty. It was the first, major scandal he was implicated in.

It wouldn’t be the last.

The Man who would be King

If the people of Judea were hoping the days of political shockwaves from Rome battering them senseless were over, events soon proved otherwise.

Just three years after one civil war propelled Herod and Antipater to the top, another came along that threatened to destroy them.

On March 15, 44 BC, Julius Caesar was assassinated in Rome by Brutus and Cassius. The deed done, the two traitors fled to the east of the Republic.

Back in the Eternal City, Mark Antony and Caesar’s nephew Octavian declared a new war to exterminate the assassins.

Unfortunately for Judea, this meant once again being caught right in the middle of things.

From his new powerbase in the east, Cassius ordered all provinces to pay for his war against Mark Antony and Octavian. That meant Judea coughing up 15,000kg of silver, or its inhabitants being put to the sword.

As procurator, the job of collecting that money fell to Antipater.

It’s possible to read Antipater’s willingness to cooperate with Cassius as a way of protecting Herod. But, given what we know about Antipater’s opportunism, it’s just as easy to imagine he’d flipped his loyalties once again, like a weasel playing Pogs.

The people of Judea certainly saw it as the latter. In 43 BC, one of Antipater’s own tax collectors assassinated him.

When Herod got the news that his father had been killed, he flew into a rage. With permission from Cassius’s forces, he tracked down the assassin and murdered him.

It could easily have been Herod’s last ever act of violence.

In 42 BC, Mark Antony and Octavian – now formed into the Second Triumvirate alongside Marcus Aemilius Lepidus – defeated Cassius and Brutus.

With the war over, Mark Antony went from warrior to avenging angel, riding across the provinces that had supported Cassius, leaving death and destruction in his wake.

This should’ve been bad news for Herod, who was suddenly stuck with explaining why Antipater had leaped into bed with Cassius.

But Herod had apparently picked up a trick or two from his old man.

He told the avenging angel “well of course daddy had to support Cassius. He’d have destroyed Judea if he didn’t. But honestly, bro, we always wanted you to win.”

How true this was is up for debate. But Mark Antony trusted his old friendship with Herod enough to buy it.

Rather than kill him, he made Herod tetrarch of Galilee – it’s ruler. And he made Herod’s brother tetrarch of Jerusalem.

Suddenly, Hyrcanus II was reduced to a figurehead. Real power in Judea now lay in the hands of Antipater’s sons.

This turned out to be a hard sell for Judea’s population.

Remember, Herod’s family were seen as not really Jewish, but fake Jews who’d got in bed with the hated Romans.

So when some dudes called the Parthians suddenly attacked in 40 BC, most Jews decided to side with them.

Amid the fighting, Hyrcanus II was put in chains, had his ears sliced off, and was dragged away to captivity in Babylon. Herod’s brother, the tetrarch of Jerusalem, committed suicide rather than face the same fate.

Of the three rulers of Judea, only Herod escaped. As the Parthians rampaged, he ran to the only safe place he could think of: Rome.

In the Eternal City, Herod was forced to beg the Second Triumvirate for help. Mark Antony and Octavian listened and finally agreed. On one condition.

Herod would have to prove himself worthy by retaking Jerusalem.

For the next three years, Herod led a Roman army against the Parthian puppet government ruling Judea.

The bitter civil war claimed many lives and ruined Herod’s reputation further among the Jewish population. But it worked.

In 37 BC, Jerusalem fell and Herod rode into the city.

Aged just 36, Herod had done it. He’d taken back what was his, and proved himself worthy to his Roman clients. That same year, he had his highest honor yet bestowed upon him.

No longer would Herod be merely tetrarch of Galilee, ruling alongside another tetrarch and a figurehead like Hyrcanus.

No, from this point on, there would be only one title befitting a warrior like Herod.

He would be King of Judea.

Death of a Republic

Herod’s first few years on the throne were spent trying to desperately apply a veneer of legitimacy to his rule.

This meant divorcing his first wife, banishing her from court, and remarrying a woman named Mariamne, who just happened to be a princess from the old ruling dynasty.

It also meant begging the now-defeated Parthians to send Hyrcanus II back from Babylon.

This might seem an odd choice. Hyrcanus was the only other guy around with a legitimate claim to Herod’s throne.

Unfortunately for Herod, though, the captured king was still popular in Judea. So Herod arranged to have Hyrcanus brought back and treated with the utmost respect – on the unspoken condition that Hyrcanus go around being all like “Gee, this Herod sure is a great king. We should probably do what he says.”

This done, Herod went about winning over the populace.

Over the next five years, he built massive new city walls for Jerusalem, and a brand new citadel to protect the Temple – named Antonia, after Mark Antony, naturally.

He even had coins minted showing himself alongside traditional Jewish objects, just to hammer home the point that he really was a Jewish king.

But, as we’ve already seen time and again in this video, the fate of Judean rulers wasn’t decided in Judea itself, but in Rome.

And Rome was already gearing up for yet another civil war.

In 33 BC, the Second Triumvirate went the way of the First Triumvirate and unceremoniously collapsed.

Two years after that, in 31 BC, Octavian and Mark Antony decided to fight each other to the death.

For Herod, this was the first time he’d found himself caught between two Roman factions without Antipater around.

This was a problem, because Herod lacked Antipater’s wily political instincts. While his father had been happy to chuck old allies like Pompey and Caesar when he thought the winds were blowing against them, Herod was just too loyal to his friends.

As the armies of Octavian and Antony gathered, Herod threw in his lot with Antony.

You can probably guess where this is going.

On September 2, 31 BC, Octavian demolished Antony’s forces at the Battle of Actium. Antony was forced to flee into hiding, where he and Cleopatra committed suicide.

At the same time, a summons landed on Herod’s desk, calling him to Rhodes to explain himself to Octavian.

If you’ve ever had to go before your boss after making some colossal mistake, you may have the faintest inkling of what Herod was feeling on that long and lonely boat ride.

Unlike when he had to explain Antipater’s actions to Mark Antony, Herod had no friendship with Octavian he could fall back on. Worse, as a guy who had literally named citadels after the defeated Antony, Herod was intimately connected to Octavian’s enemy.

Perhaps it says something of Herod’s state of mind that his last act before leaving Judea was to execute Hyrcanus II. That way, if he Herod was executed in turn, at least the throne would stay in his family.

But it turned out Herod really could be as wily as Antipater.

Once in Rhodes, Herod didn’t even bother trying to lie. He boldly told Octavian that he had supported Mark Antony to the death, that he’d been loyal to the general for decades, and would remain loyal even now.

Octavian listened and, when Herod was done, presumably gave a wry smile, before saying that Herod’s loyalty was a far more useful asset to Rome than someone who would try and worm their way out of trouble. He then reconfirmed Herod as King of Judea.

It’s hard to imagine what must have been going through Herod’s mind on the boat ride home.

Against all the odds, his truth-telling gamble had paid off. Octavian might not exactly trust him, but he certainly respected him. And in Octavian’s good books was exactly where the King of Judea wanted to be.

Some three years after the meeting in Rhodes, Octavian finally completed his takeover of the Roman Republic. He took the name history now knows him by: Augustus.

After a half century of bloodshed, Rome’s transformation into an Empire was finally complete.

The Good King

With the drama of the Empire’s creation out of the way, Herod was able to finally settle into actually ruling Judea.

Between 27 and 20 BC, he built up an image as a sort of Pagan Jewish ruler, one he hoped would appeal both to Judea’s population and his Roman backers.

But if neither side was ever really convinced by Herod’s posing, they couldn’t ignore his material achievements.

As King of Judea, Herod spent his time building new stuff like a cocaine-addicted Bob the Builder.

Jerusalem got a new amphitheater, market, royal palace, and a ton of new homes to replace those destroyed by an earthquake.

New aqueducts brought fresh water into the city. On the fringes of Judea, huge new fortresses were built to protect the kingdom. Some of these, such as Masada, are still extant and still impressive.

Then there was the money spent abroad, shoring up Judea’s image.

Iconic cities like Damascus and Beirut were given Herod-sponsored makeovers. When the Olympic Games threatened to go bankrupt, Herod stepped in and saved it.

This largesse was accompanied by an unmistakable increase in Judean power.

Augustus twice visited Herod in Jerusalem, and each time he handed over new land to the king.

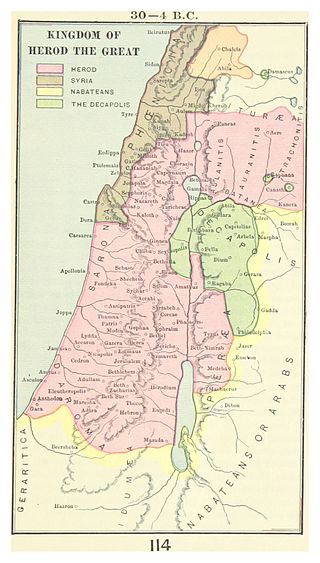

By 20 BC, Judea had expanded to include swathes of modern Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan.

As Judea’s prestige grew, those in Rome took notice. Soon Jerusalem was flooded with Roman playwrights, historians, and philosophers, all eager to see the booming city state.

And you better believe Herod tried to use this power for good. He was a vocal defender of Jews living in other states, often going out of his way to appease their Gentile hosts.

But of course this is still Herod we’re talking about. Underneath all this glitz and glamor lurked a dark side.

On the streets, ordinary Judeans were suffering enormous tax burdens to pay for Herod’s projects.

On top of that, there were uneasy questions hovering over Herod’s Jewishness. With his fondness for pagan, Roman things, many in Jerusalem believed their ruler was trying to stealthily sabotage their culture.

Not that it was all bad for ordinary men and women. During the horrific famine of 25 – 24 BC, it was Herod’s Roman contacts that stopped the disaster by arranging huge shipments of grain to Judea.

But it wasn’t until 20 BC that Herod’s made his greatest attempt to win Jewish hearts.

He decided to rebuild the Second Temple.

Way back in 519 BC, the Neo-Babylonians had destroyed the First Temple. A replacement had since been built, but it was the very definition of “modest”.

Under Herod, that was about to change.

Everything you think of when you think of Jerusalem’s Temple was a result of Herod’s construction spree.

The sweeping walls, vast towers, and great courtyard covering the Temple Mount all came into being because of Herod. The famous Western Wall you can still see standing today? That’s another Herod project.

Not that this grand new Temple mollified everyone.

Herod kitted it out with too many Roman touches, too many architectural nods to Judea’s imperial overlords.

Nor did he take criticism kindly. When a small sect of radical Jews tore down a Roman eagle symbol from the new Temple, Herod had them all burned alive.

Still, as Herod entered the last decade of his life in 14 BC, the signs were all there that he might go down in history as a not so bad ruler. That he might even live up to his billing of Herod the Great.

But you and I both know that there’s one more act to come.

The Massacre of the Innocents

One of the fascinating things about Herod is that, despite still being a household name 2,000 years later, he often feels like he was only ever a bit player in two major stories.

For most of his life, the story Herod appeared in was the epic novel The Rise of the Roman Empire. But, as he entered his old age, the King of Judea found himself cast as the villain in an even more famous tale.

That’s right, it’s time for us to talk about Jesus.

There’s a long-running debate about Christ’s exact birthdate, with anywhere from 6 BC to 4 BC being generally accepted.

Whichever is true, by the time Christ was born, Herod’s rule was in a very bad place.

The trouble had really started in 10 BC, when Herod had waged war against the Nabateans and so screwed up the campaign that he’d fallen from Augustus’s favor.

This sudden demotion in status seems to have triggered a crisis of paranoia in the king.

Convinced supporters of the dead Hyrcanus II were plotting in the shadows, Herod began a ruthless campaign to root out suspected enemies.

He’d already put his wife Mariamne to death, but now he also had her brother, mother, grandfather and children all killed.

Herod even had two of his own sons, Antipater and Aristobulus, executed. When Augustus heard, he joked it would be safer to be Herod’s pet pig than one of his sons.

Nor were those outside Herod’s court safe.

In his last years, Herod had hundreds of ordinary Judeans thrown in dungeons and tortured. He masterminded gruesome public executions to keep order.

Rumors started to swirl that he had defiled the tombs of David and Solomon. That he’d taken nine wives, in defiance of Jewish customs.

Although there were still triumphs – such as the opening of Herod’s great new port city of Caesarea in 9 BC – they were overshadowed by a cloud of paranoia hanging over Judea.

It wasn’t helped by a horrific illness the king contracted that ate away at his flesh, thought today to have been Fournier’s gangrene.

The disease left Herod so mad that he gave insane orders, from the mass execution of 300 soldiers to a demand that all the Judean nobles be dragged to an amphitheater on his death and shot full of arrows.

It was against this dark background that a sect of Jewish scholars suddenly announced the time of the Messiah was almost upon them.

And so we come to Herod’s most infamous legacy.

Matthew 2:16-18 tells us that Herod became worried about the prophesized Messiah, eventually ordering every child under two in Bethlehem put to death.

Known as the Massacre of the Innocents, the killing is controversial among historians today because it only appears in Matthew’s gospel. The other gospels don’t mention it, nor do the accounts of Josephus or Nicolaus of Damascus.

Still, from what we know of Herod’s mental state in his last years, having a bunch of random babies killed would’ve been completely in character.

Thankfully, the massacre would be the last awful thing the King of Judea ever did.

In 4 BC Herod the Great finally passed away in Jericho, only a handful of months after a failed suicide attempt. Traditionally, it’s thought he died in March, although no-one really knows for sure.

After his passing, Augustus decreed Judea would be split into three parts. The kingdom Herod had helped create was no more.

In the end, the life of Herod was defined less by who he was than by those who were around him.

The lives of Julius Caesar, Mark Antony, Augustus and, of course, Jesus continue to fascinate us even now, two millennia later. To have been a part of all their stories is a remarkable achievement in itself, even if Herod may not have seen it that way.

The poem Ozymandias by Percy Shelley tells of a traveler who finds a great, broken statue of some king in the middle of a desert. Although the statue’s pedestal declares “Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!” there is nothing left of this dead king’s deeds. No hints of his life. Just endless sand.

In the desert of history, it’s tempting to think the same has come of Herod, with his name still only just about visible thanks to a single verse in a single book of the Bible. But, as this video has hopefully shown, there was more to the life of Herod than one horrific act.

He may not have been a good man, or even a particularly clever man, but Herod the Great was certainly one thing. He was a man worth remembering.

(Ends)

Sources

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Herod-king-of-Judaea

https://www.livius.org/articles/person/herod-the-great/

(Original 1906 text, good for some details, but obviously outdated in others): http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/7598-herod-i

(Interesting notes on why Josephus and others may not mention Massacre of Innocents – size of Bethlehem plays a key role): http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity/history/herod.shtml

Pompey’s siege of Jerusalem: https://www.livius.org/articles/concept/roman-jewish-wars/#Hyrcanus

Hyrcanus II: https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Hyrcanus-II

(A dissenting opinion): http://www.jvl.leverage.it/herod