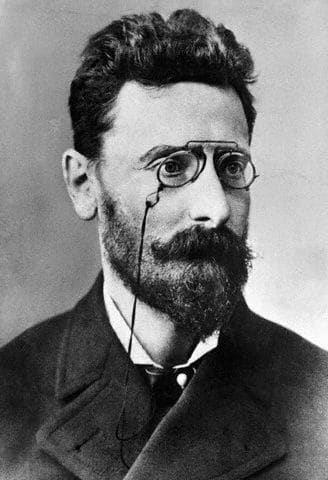

Three-time Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Arthur Krock described Joseph Pulitzer as having “a shining personal character, humility in possession of power and compassion for the unfortunate. He hated cant, sham, injustice, and corruption and was incapable of any of these.” Other people described Joseph Pulitzer as “the greatest journalist on earth,” or “the most interesting man on the planet.” His life was said to resemble “a story out of the books of giants, goblins, and fairies.”

For many contemporaries, Joseph Pulitzer was the perfect example of the “American Dream” – he was an immigrant who came to America all alone, with no money, and without even speaking the language. But he worked hard all day every day, and he made something of himself, becoming one of the most influential voices in the country.

His story was a refreshing change of pace from most other businessmen of his era who inherited fortunes and enlarged them through dishonest, underhanded, even fraudulent means. But Pulitzer himself was hardly innocent. In their pursuit of success, his newspapers chased sensationalism, sex, scandal, murder, and fearmongering, while qualities such as fairness, accuracy, and accountability were often left by the wayside. This approach, which became known as yellow journalism, has infected almost every facet of the fourth estate and is still prevalent today.

Early Years

Joseph Pulitzer was born on April 10, 1847, in the town of Makó in southeastern Hungary, the second of four children to Philip Pulitzer, a successful Magyar-Jewish grain dealer, and Louise Berger, a Catholic Austro-German.

By 1853, Philip Pulitzer had made enough money from the grain business to retire and move his family to Budapest. He later died of heart disease when Joseph was 11 years old. A few years later, Joseph’s mother got remarried to a businessman named Max Blau who developed a hostile relationship with his step-children. We don’t know specifics about what happened. We just know that Pulitzer hated Blau and couldn’t wait to leave home.

When Joseph reached the dreaded stage of puberty, he shot up like a beanpole. As a teenager, he was about 1,9m tall (or almost 6 ft 3 in freedom units), but he was very skinny, to the point where he always looked ill and emaciated. This proved to be a problem when the 17-year-old Pulitzer tried to enlist in the Austrian army, hoping to follow in the footsteps of two uncles who were both officers. Unfortunately, Joseph was told that he was too gaunt, too young, and his eyesight was too bad, so he was rejected.

Undeterred, Pulitzer traveled to Paris, looking to join the French Foreign Legion, but they gave him the same answer. He then went to London, hoping he might get sent to India, but was rejected again. After that came Hamburg, where Pulitzer tried his luck as a sailor, but still no go.

For a while, it looked like nobody was desperate enough to accept this nearsighted, skinny Hungarian kid, but fortunately for Joseph, while in Hamburg, he ran into recruiting agents for the American Union Army. These agents received bounties for every soldier they signed, so they were ready to take anyone willing to put their mark on the dotted line. And so it was that in 1864, Joseph Pulitzer packed up his things and went aboard a rickety ship that crossed the Atlantic crammed with a throng of emigrants looking to make it big in America.

While docking into Boston Harbor, Pulitzer jumped overboard into the cold water, swam to shore, and traveled to New York alone by train. He did all of this so he could collect the $300 enlisting bounty himself.

On November 12, 1864, Pulitzer made it to Remount Camp in Maryland where he joined the L Company of the First New York Lincoln Cavalry, although he only ever took part in a few minor skirmishes. He was quickly disabused of whatever glamorous notions of the military life he might have gained from his uncles. His captain took an instant dislike to him due to his weak, scarecrow-like constitution and heavily-accented, broken English. The other soldiers followed their captain’s cue and also mocked the new recruit. Instead of Pulitzer, they called him “Pull-it-sir” and considered it an invitation to grab Joseph’s prodigious nose.

Once the war was over, what was next for young Joseph? Definitely not a military career, that much was clear. He was broke, sleeping on the streets of New York. The city saw a large influx of veterans, so finding any kind of job was difficult. Pulitzer spoke almost no English, but was fluent in French and German, so he thought he would move to a place with a large German population. He sold his last worldly possession – a white silk handkerchief – and used the money to buy food and a ticket to St. Louis.

Journalism & Politics

In October 1865, Pulitzer arrived at his new home. At first, he was desperate for any kind of work he could get. He served as a coal shoveler, then a mule caretaker, stevedore, laborer, deckhand, and waiter. All of them were dead-end jobs that paid chicken feed, so Pulitzer had to work two jobs at a time, 16 hours a day, just to barely make ends meet, plus another four hours spent at the library learning English. The librarian there, Udo Bachvogel, became his first friend in America and helped Pulitzer learn the language by carrying out conversations in English.

One day, Pulitzer and 40 other people got scammed by a con artist who promised them great jobs on a plantation in Louisiana. The marks each paid him $5 and then boarded a steamboat that simply dumped them in a remote area about 40 miles from St. Louis. Apparently, it took them three days without food or water to make it back to the city. It was an awful ordeal but, for Joseph Pulitzer, it turned out to be the best thing that ever happened to him.

A local reporter heard the story, tracked down Pulitzer, and convinced him to write an account of the experience for the German-language newspaper Westliche Post. He did well enough that the editor asked him to keep writing. Immediately, Pulitzer discovered that he had a knack for journalism, but the sparse assignments weren’t enough to pay the rent. Fortunately for him, at the newspaper building, he made the acquaintance of two lawyers who got him a recordkeeping job with the Atlanta and Pacific Railroad. As it turned out, Pulitzer had a knack for that, as well. The attorneys encouraged him to enter law school and even gave him free access to their library so he could study at his leisure.

A few noteworthy things happened in the years that followed. Joseph Pulitzer became an American citizen. His younger brother, Albert, joined him in St. Louis and became a German teacher. And Pulitzer was admitted to the bar and became a notary public. His new career, however, wasn’t a hit. Joseph still struggled with English. He didn’t have money to spend on smart-looking clothes. His odd, scruffy appearance didn’t attract many customers. He had to give up the exhilarating life of a notary public, but the timing worked out great because the Westliche Post was looking for a new full-time reporter and he got the job.

Pulitzer was a complete workaholic. He routinely worked 16 hours a day, chasing down every lead and questioning every person with unbridled enthusiasm. His editors loved him, but his fellow journalists resented him for making them look bad. On more than one occasion, Pulitzer was sent out on a wild goose chase, but this never dampened his spirit.

His entry into the world of politics was just as serendipitous. Pulitzer joined the Republican Party, like many of his newspaper colleagues. On December 14, 1869, he attended a Republican meeting as a reporter. They needed to put forward a candidate for the Missouri state legislature. Because everyone thought that the Democrats had the election in the bag, someone nominated Pulitzer, as a joke. The rest of the crowd laughed and unanimously selected Pulitzer as their candidate.

And guess what? He freakin’ won! Pulitzer put the same amount of effort into his election race as he did into his reporting. He campaigned in the streets, visited people at home, and displayed a genuine enthusiasm that struck a chord with the voters.

Technically, the moment Pulitzer took his seat, he was breaking the law because he was three years too young to serve in the legislature. If anyone realized this, they kept it quiet and Pulitzer served out his term illegally. His most notable contribution was voting to support the Fifteenth Amendment, which gave Black men the right to vote.

Pulitzer’s other highlight from his time as a state legislator generated a lot more headlines. It was a rivalry between him and a Democrat opponent named Captain Edward Augustine, which culminated in a fight inside the lobby of Schmidt’s Hotel in Jefferson City, where Pulitzer pulled out a gun and shot Augustine twice.

What exactly happened has never been made clear since newspapers told different versions based on whom they supported. They all agreed that Augustine taunted and insulted Pulitzer several times, but the pro-Pulitzer papers said that Augustine was armed and charging at his enemy when Pulitzer shot him in self-defense, while the pro-Augustine camp claimed that Pulitzer shot an unarmed man.

Ultimately, Pulitzer was charged with assault with intent to kill. He was even found guilty but was let go with only a $405 fine.

Media Mogul

After his term was done, Pulitzer remained involved in politics but grew increasingly disillusioned with the Republican Party. Pulitzer was the kind of man who would never put party over principles, so when he perceived that the Republicans were showing signs of corruption or incompetence, he distanced himself from them. For a while, Pulitzer joined the short-lived Liberal Republican Party, which opposed Ulysses S. Grant’s presidential nomination and instead campaigned for New York Tribune founder Horace Greeley.

For Pulitzer, the last straw came when the Republican Party backed Rutherford B. Hayes for president during the 1876 election. He switched to the Democrats and began campaigning for New York governor Samuel Jones Tilden. Pulitzer was so fiery and impassioned whenever he spoke in public that, during one speech at the Cooper Union in New York, he burst a blood vessel and started coughing up blood halfway through, but still finished his talk in front of a standing-room-only audience.

Pulitzer had another close call on his 30th birthday when the hotel he was staying at caught fire. The alarm wasn’t working, so many residents were only made aware of the fire by the frantic screaming and chaos that was happening outside. Seventeen people perished in the blaze and Pulitzer himself was almost among them before being rescued. But let’s take the bad with the good. Soon after the fire, Pulitzer moved to Washington, D.C., where he fell in love with 23-year-old Kate Davis. The two got married on June 19, 1878, and went on to have seven children together.

All the while he was involved in politics, Pulitzer never abandoned journalism. His dream was to have his own newspaper, but he wasn’t exactly rolling in dough yet. In late 1878, he learned that the St. Louis Dispatch was up for sale after going bankrupt. Pulitzer only had around $5,000 to spend, so to prevent any outside interest, he sent a covert emissary to bid on his behalf and managed to buy it for half his budget. More good news followed because the publisher of one of the newspaper’s main rivals, the St. Louis Post, called up to offer a merger because he didn’t want to compete. And thus, at 31 years old, Joseph Pulitzer owned his first newspaper – the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

The paper’s circulation steadily rose under Pulitzer’s leadership and became one of St. Louis’s main political voices, usually staying true to Pulitzer’s pledge that “the Post and Dispatch will serve no party but the people.” Immediately, he started a fight with the bigger, more established Missouri Republican which, despite its misleading name, was published by Democrat William Hyde. Guess it was “opposite day” in St. Louis when they named their newspapers because another one of Pulitzer’s competitors was the Globe-Democrat which, you guessed it, was actually a Republican newspaper.

Pulitzer’s aggressive tactics of picking fights with virtually every other print publication in the city brought new readers to the Post-Dispatch. Besides politicians, Pulitzer also crusaded against a lottery racket, a horse-car monopoly, and the gas company, and this was just in the first few months. In a short time, Pulitzer had made quite a few enemies, so he got into the habit of walking around with a pistol. So did his editor, John Cockerill, and he actually got a chance to use it.

In 1882, there was an election to fill the seat of deceased Congressman Thomas Allen. The Democrats backed a lawyer named James Broadhead, but Pulitzer strongly opposed him. Consequently, Broadhead became the Post-Dispatch’s new prime target. Broadhead himself didn’t respond to the attacks, but his friend and law partner Alonzo Slayback did. On October 13, Slayback charged into the offices of the Post-Dispatch and launched a virulent and threatening tirade at Cockerill. In return, the editor opened his desk drawer, pulled out his gun, and fired, killing Slayback almost instantly.

The story became a big sensation. Newspaper employees testified that Slayback had a gun in his hand and was aiming it when Cockerill opened fire. Other papers, however, were giddy with excitement at the opportunity of taking down the Post-Dispatch, and many of them portrayed Slayback as an innocent, unarmed man murdered in cold blood. At one point, the Missouri Republican whipped up its readers in such a frenzy that a mob formed outside the offices of the Post-Dispatch, looking to burn the whole place down.

Ultimately, Cockerill was exonerated during his trial, but the court of public opinion wasn’t as merciful. The circulation for the Post-Dispatch plummeted. Advertisers left in droves. Pulitzer’s personal reputation took a big hit and his family had become socially ostracized. He felt like maybe it was time for a change.

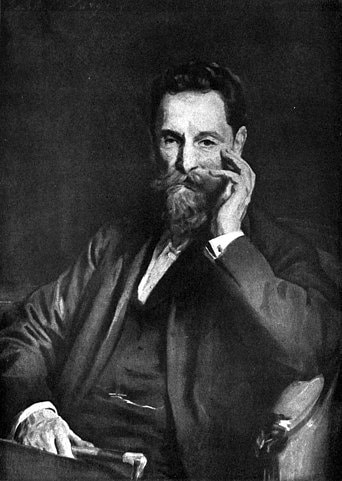

Pulitzer Buys The World

The aftermath following Slayback’s death took its toll not only on Pulitzer’s business but also on his health. In the spring of 1883, Joseph and his wife traveled to New York, intent on going on a long European vacation to rest up. However, while in New York, Pulitzer heard that infamous robber baron Jay Gould was looking to sell his newspaper, the New York World. For years, Pulitzer dreamt of running a publication in the Big Apple, so he entered negotiations with Gould, and, on May 10, 1883, Joseph Pulitzer bought the New York World for $346,000.

Just like the Post-Dispatch, Pulitzer announced in the first issue under his ownership that, from then on, the New York World would be “dedicated to the cause of the people rather than the purse of the potentates, will expose all fraud and sham, fight all public evils and abuses [and] serve and battle for the people with earnest sincerity.”

Basically, Pulitzer wanted his newspaper to be aimed at immigrants and the working class. He knew this was the strategy that brought him to the dance and he had no reason to switch it up now. Most of New York’s politicians and businessmen became equal-opportunity targets, including the World’s former owner, Jay Gould. There was a rumor going around that Gould remained a secret partner in the newspaper. Pulitzer feared this would ruin his “champion of the underdog” credentials so he made sure that Gould bore the brunt of his literary attacks, just to show that the two are not on the same side. Not that Gould didn’t deserve it. He has his own Biographic we made a while back. You can check that out if you want to learn about all the shenanigans he got up to.

As a consequence of focusing on the common man, the newspaper began covering a lot more human interest stories. At first, these were only present in the Sunday edition, which Pulitzer used as a sort of testing ground for his new ideas. It featured stories about cannibalism at sea, crazy religious sects, human sacrifice in the United States, and, of course, murder after gruesome murder. One particularly infamous headline even read “French Scientist and Explorer Discovers a Race of Savages with Well-Developed Tails.”

It didn’t take Pulitzer long to realize that the more lurid, scandalous, or violent the story was, the more copies it sold. Soon enough, such accounts made their way from the Sunday edition into the weekday papers. The New York World became the progenitor of the tabloids of today, where sensationalism, scandal, and fearmongering triumphed over fairness, accuracy, and integrity.

But it wasn’t all bad, to be fair. The World had its moments. It exposed many tales of fraud and corruption, both in the public and private sectors. It recruited intrepid journalists who conducted genuine investigations, the most famous of all being Nellie Bly. It organized stunts and promotions that, ultimately, benefited society even though their main goal was to sell newspaper subscriptions. The most memorable one involved raising funds to build a giant pedestal in New York Harbor for the Statue of Liberty. Neither Congress nor New York Governor Grover Cleveland wanted to pony up the dough, so it is entirely possible that, without Pulitzer’s help, the Statue of Liberty might have been shipped back to France.

War with Hearst

Pulitzer’s hard work, aggression, and sensationalism turned the New York World into the best-selling newspaper in America and him into a rich man. But the effort took its toll on his body. Remember that he was never really the picture of health, plus he worked himself ragged, 12-to-16 hours a day, for most of his adult life. Add to that the stress of his job and Joseph Pulitzer had become a frail and sickly man, even though he was only in his early 40s. His asthma was getting worse, his eyesight was almost gone, his nerves were shattered, and he developed an extreme sensitivity to noise, so much so that he had to soundproof the rooms where he spent most of his time. Pulitzer spent several years traveling abroad, meeting with numerous medical experts, but he ended up ignoring their advice since they all told him the same thing – he needed to retire.

All the experts thought that the job was killing Pulitzer. However, that was the one thing he would never give up since he thought that his work was keeping him alive. But Pulitzer did admit that he could no longer function as before so, begrudgingly, in 1890 he retired from the editorship of the World, although he still managed it in absentia from the comfort of his own home.

Even though Pulitzer was supposed to take it easy, his biggest challenge was yet to come. It arrived in the form of publisher William Randolph Hearst, who purchased the New York Journal in 1895, a newspaper originally founded by Pulitzer’s younger brother, Albert. Hearst went after the same audience as the World, using the same approach to journalism. His strategy seemed to be “do what Pulitzer does, but do it bigger” and he had the funds to back it up. Hearst poached Pulitzer’s people with better salaries and he initially sold his paper at a loss just to make it cheaper than the World. There was also personal animosity there. Pulitzer respected hard-working, self-made men, while he had contempt for people like Hearst, who were playing the game with daddy’s money.

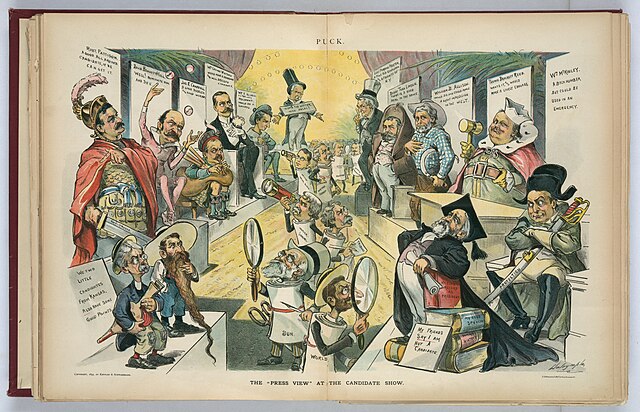

This rivalry soon evolved into a journalistic war that went on for years and constituted the most shameful period of Pulitzer’s life. The reality of the matter was that, when his back was against the wall, Pulitzer discarded whatever principles he claimed to have and descended fully into irresponsible, sensational, and, sometimes, purely fabricated journalism just to sell more copies than his rival. For his part, Hearst had no qualms about matching Pulitzer move for move. This explicit and unrestrained style, which is still pervasive today, became known as yellow journalism. And in case you’re wondering, the name was derived from the fact that both publishers fought over the services of cartoonist Richard Outcault, who had a popular comic strip titled “The Yellow Kid.”

![From Wikimedia Commons: Looking north across 73d Street on a cloudy day [at Joseph Pulitzer's house]. Credit: Jim.henderson - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0](https://biographics.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/640px-Joseph_Pulitzer_house_7-11_W73_jeh.jpg)

The rivalry reached an unprecedented height when Cuba revolted against Spain, and there was serious concern in America that the US might go to war with Spain. Both publishers realized that a war would sell a buttload of copies, so they basically turned their newspapers into fearmongering propaganda in order to make the public favor going to war. It was similar to the plot of Tomorrow Never Dies which would make both Pulitzer and Hearst real-life Bond villains.

To be fair, Pulitzer did feel a modest pang of guilt and started adopting a more restrained approach to journalism following the Spanish-American War. In 1904, he hired Frank Cobb as the new editor of the World, and he resisted Pulitzer’s attempts to continue running the newspaper from home. Pulitzer didn’t like it, but he respected Cobb, so eventually, he relented and handed over the editor reins. In 1907, he turned the administrative side of the business over to his sons and retired altogether. Joseph Pulitzer died aboard his yacht a few years later, on October 29, 1911, aged 64.

Meanwhile, Hearst continued on his path unimpeded and he eventually amassed the largest media empire in America, although he did have the benefit of outliving Pulitzer by 40 years. But he is remembered today as a ruthless muckraker who made his fortune off other people’s misery and disgrace, whereas Pulitzer mostly rehabilitated his image thanks to a generous will. He used his money to found the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, one of the first and finest in the world, and, of course, the Pulitzer Prizes for journalism, which remain, to this day, his most enduring legacy.