Depending on where your moral compass points to, you may consider today’s protagonist as a legend of colossal proportions, or as the ultimate scumbag. Ordained Pope barely out of his teenage years, he went down in history as the most outrageous of Rome’s Bishops.

He favored sword and armor to the mitre and the cross.

He’d rather go hunting, than celebrate mass.

He led invasions, plotted against his friends, and signed alliances with his enemies. He gambled, he drank, he toasted the Devil and performed gruesome acts of violence with oblivious abandon. And all the while, he gallivanted around Rome with the obstinate copulating stamina of a Duracell bunny in heat.

Fittingly, this young pope went out with a bang – in more than one sense.

Well, at least that’s one version of the events. Join me today for the chronicle of what may have been the most disastrous papacy in history. This is the story of Octavianus, son of Alberic of the Counts of Tuscolo, better known as Pope John XII.

You Slapped the Wrong Guy

Let’s start with some context. In the 10th Century AD, the Italian peninsula was kind of a mess. And I know perfectly well that I am oversimplifying here, so be merciful in the comments.

Most of the peninsula’s northern half was governed by the Kingdom of Italy. The style of King of Italy, however, was little more than a nominal title, as the real military power lay in the hands of powerful feudal lords.

Still, the Italian crown carried some prestige and privileges. Kings of Italy could aspire to offer their protection to the pope, and in exchange expect to be crowned Holy Roman Emperors.

Let us now meet the father of our protagonist.

He was one of those feudal lords I mentioned. His name was Alberic, and his family hailed from Spoleto, a town 130 km north of Rome.

In 932, Alberic’s mother, Marozia, married her third husband, the Marquess Hugh of Provence. This nobleman happened to be also the then King of Italy. As such, he was expecting to be crowned Holy Roman Emperor, too.

The wedding took place in Rome, a city which Hugh sought to claim as his personal dominion.

But his overambitious plans were soon to be thwarted.

The local aristocracy was not happy with the idea of a foreign Marquess lording it over Rome. They started to conspire, rallying behind Alberic as their leader.

Alberic was looking for the right occasion to rebel against his step-dad.

The occasion presented itself shortly after the wedding.

Marozia asked Alberic to pour some water for Hugh to wash his hands. Alberic complied reluctantly, which Hugh interpreted as a sign of disrespect. He slapped his stepson, and the two got into a fight. Days later, Alberic got word that Hugh was planning to get back at him by gouging his eyes. This was the moment to rebel! The Italian nobleman moved quickly to the offensive.

He rallied the Roman aristocracy and the populace into an uprising, defeating Hugh and driving him away from the Eternal City.

Alberic became the de facto ruler of Rome until his death, in August of 954. Before shuffling off the mortal coil, he forced the Roman nobles to take a pledge: they would elect his son Octavianus as next pope and Lord of Rome.

Now, we know very little about the boy’s early life, or even the circumstances around his birth.

According to some sources, Octavianus was born in 937, to Alberic and his wife Alda – who happened to be his stepsister, too.

What a confusing, confusing age.

According to others, the future pope had been born in 930 to an unnamed concubine of Alberic’s. Octavianus became the 130th Pope in December of 955. Depending on the origin story, he may have been 25, or barely 18.

In any case, it probably was a tad too early to take on such responsibilities!

But the young pope accepted his destiny, choosing the name John XII.

As elected pontiff, and son of Alberic, he could claim both spiritual authority over the Catholic Church, and temporal authority over Rome and the surrounding Ecclesiastical States.

Poor General, Master Schemer

From the very start of his reign, contemporary chroniclers observed that his character was unsuited to the task. John was impulsive, coarse, immoral, and more interested in earthly desires than the Christian faith.

As the energetic son of a feudal lord, he loved to hunt with bow and arrow, he held several mistresses, and had a thirst for combat. John, however, was not just some medieval Chad looking for a random fight. He did have a clear agenda, one already set in motion by his dad Alberic.

Since the times of Charlemagne, popes had been entitled to the ‘Patrimonium Petri’ – the Patrimony of Peter. The term indicated prized territories north and south of the Ecclesiastical States.

In the decades after the death of the Frankish emperor, though, these lands had been seized by other lords.

It was time to reconquer those fiefdoms: the young pope unsheathed his sword and led his armies in what should have been a glorious campaign.

But no, it was a disaster.

John wanted too much, too soon.

To the north, he attacked the Exarchate of Ravenna, initiating a conflict with the new King of Italy, Berengarius II, and his son Adalbert.

At the same time, he took on the Duchy of Capua, south of Rome.

He was quickly defeated in both campaigns and suffered a further humiliation when Berengarius marched on to pillage the Ecclesiastical States, in 960.

John needed allies, and quickly!

He knew that he would find no love amongst Italian lords. Even Roman aristocrats were turning against him, wary of his inexperience and lack of morals. In a shrewd diplomatic move, the young pope sent two emissaries to the court of Otto I, the powerful Duke of Saxony and King of East Francia.

The ambassadors proposed a military alliance to Otto, probably with the promise of raising him to the rank of Holy Roman Emperor. An offer he could not refuse, indeed.

Moreover, Otto already had a beef with Berengarius.

Do you remember Hugh of Provence, the step-dad of Alberic? The King of Italy who had lost Rome after slapping his stepson? Yes, that guy!

Well, he had died back in 947. The Crown of Italy had been handed down to his son Lothar.

Who also died, shortly thereafter.

His widowed wife, Adelaide, was still crying over his body, when another feudal lord swept in and seized the Italian throne.

That other lord was Berengarius, until now a mere Marquess.

Adelaide needed some help against the usurper and so she appealed to Otto, offering her hand in marriage. So, back in 951, Otto had already organized an expedition to Italy, to fulfill the wishes of his new wife. But he had to cut short the invasion to deal with a revolt in Swabia, and then to repel a Hungarian attack.

Now, Otto had a fresh casus belli: time to settle scores with those who had wronged his lovely lady wife!

The Ottonian Privilege

The German nobleman descended into Italy with a mighty army, whose ranks were swelled by the local lords who opposed Berengarius. Attacked from all sides, the King had to retreat to his fortress.

Otto continued his descent towards Rome, sending an envoy to John XII in December 961.

In his message, Otto pledged to protect the person, the life, and the honor of the pope with all his might. He also committed to restoring the Patrimony of Peter and to consult the Pope on any decision concerning the papacy and the city of Rome.

In his reply, John solemnly pledged friendship to Otto. He also promised that he would never ally himself with Berengarius or his son Adalbert.

But, apparently, John did not entirely trust the promises of the German king. Having powerful protectors is very useful, provided they fornicate off back to their country once the war is over. But what if they decide to stick around? What if they decide to turn that pledge of protection to thirst for control?

That was John’s fear: could the emperor be planning to undermine Papal authority?

Nonetheless, John fulfilled his part of the deal.

Otto and Adelaide reached Rome in January of 962. And on the 2nd of February they were crowned Holy Roman Emperor and Empress.

Immediately afterwards, John convened a council of bishops, in which he sanctioned one of Otto’s pet projects: the foundation of an archbishopric in Magdeburg, with the aim of evangelizing the Slavic peoples.

Surely pleased by this concession, the newly crowned Emperor issued the so-called ‘Privilegium Ottonianum’, or Ottonian Privilege.

With this document, Otto confirmed his previous pledge of restoring the Patrimony. Then, he collected his army and marched back to the north, to resume his siege against Berengarius.

So, everything appeared fine and dandy for the pope, right?

His new BFF had his back covered, and had decided not to make himself cozy in Rome. But the Privilege contained a clause which John didn’t like one bit: future popes were required to pledge their obedience to the emperor.

John may have been a serial libertine, but he was still the representative of Christ on Earth. Surely it should have been the other way around: emperors had to bow to popes!

In autumn of 962 he organized a second council in Pavia, northern Italy, in which he yielded for the last time to Otto’s requests: namely reinstating some bishops which had been expelled from their seats.

But at the same time, he was scheming behind Otto’s back.

He negotiated a secret alliance with his old enemies Berengarius and Adalbert, with the purpose of booting the emperor out of the Italian boot. News of the alliance leaked to Otto. The dumbfounded emperor could not believe his ears and sent envoys to Rome to investigate.

One of them, bishop Liutprand of Cremona, confirmed the rumors upon his return.

Moreover, the bishop reported how the dissolute lifestyle and poor administration of John XII had left Rome an absolute shamble.

Poor Schemer, Worse General

While Otto processed the treason, John doubled up.

He sent a team of bishops and cardinals to the Byzantine Empire and to the Kingdom of Hungary, seeking to create a vast anti-imperial alliance.

Unfortunately for him, two of them were captured by his old enemy, the Duke of Capua. The letters they carried were solid proof of the pope’s schemes. If John had had his way, Otto would face defeat in Italy, and an invasion in his homeland!

The cat was now out of the bag, and John tried to put a plaster over the whole mess.

He hastily sent a message to Otto, claiming that the letters seized in Capua were just a forgery, concocted to undermine their friendship.

He took the occasion to accuse the emperor of not fulfilling his promise of restoring the Patrimony. You see, Otto had reconquered some of the lost ‘lands of Peter’, but he had not returned them to papal authority yet.

If anything, he was the traitor!

Otto reacted immediately by sending Liutprand to Rome, to refute these allegations.

Liutprand even challenged John to solve their quarrel with a good old trial by combat!

As much as we would have loved a duel between a Papal Mountain and an Imperial Viper – or vice versa – John rejected the idea and sent Liutprand packing.

Shortly afterwards, Adalbert entered Rome to formalize his alliance with John.

Well, this was outrageous! Otto now had no choice but to take matters into his own hands! He regrouped his armies and marched towards the Eternal City in November of 963. John donned his armor and rallied his troops, ready to face the emperor in a bloody siege. But he had not accounted for enemies within the city walls.

More and more Roman aristocrats were sick and tired of the dissolute pope, and had no sympathy for Adalbert. They organized a revolt and defeated the papal faction, welcoming Otto with open arms.

John and Adalbert had no choice but to flee to nearby Tivoli – carrying a good chunk of the Church’s treasure with them!

The Romans were not done with John, though.

On the 6th of November they organized another council of bishops, with the purpose of trying the pope in absentia.

A Judas and a Devil

Our old friend Liutprand of Cremona penned an account of the trial, which gave us the full extent of the pope’s alleged crimes. The pontiff came out with a rap sheet as long as my arm.

He was accused:

Of celebrating mass without receiving the communion first,

Of not respecting the canonical times for prayer,

Of ordaining a deacon at a strange time of the day – whilst standing inside a barn(!),

Of appointing a 10-year old bishop, and selling other bishoprics for money.

Moreover, John had committed sacrilege and perjury, he openly carried weapons and hunted with bow and arrow.

If that wasn’t enough, he was indicted for:

Adultery!

Incest!

The concoction of diabolical love potions!

But there is more!

The pope was charged with grievous bodily harm and murder! Apparently, he had ordered his godfather to be blinded. Another high ranking cleric – a cardinal, no less! – had been castrated and then killed by the papal goons!

Liutprand also specified that John XII loved to drink and to gamble, toasting to Satan or invoking pagan deities before each roll of the dice.

Finally, under his administration, churches had been left in a state of abandon and disrepair. The papal residence, the Lateran Palace, had been turned into a brothel.

Oh, and I almost forgot: he didn’t do the sign of the cross!

In his account, Liutprand of Cremona explicitly compared the pope to Judas and to the Devil himself.

Now, such a tsunami of allegations would have left the whole Borgia family seething with envy – had they been born some centuries earlier. But I should specify that contemporary historians are a bit skeptical about the extent of such charges.

Sure, other sources confirm John’s licentiousness and disregard for good admin practices,

but Liutprand’s writings should not be taken as Gospel.

After all, he was a loyal servant to Otto, and his record of the trial was probably more of an exaggerated propagandistic pamphlet than an honest transcript.

Unsurprisingly, John refused all the allegations from his hiding place, and issued an excommunication for all involved in the council. Nonetheless, on the 4th of December 963, the convened bishops issued their verdict, pressured by Otto: John was to be deposed, and a new pope to be elected.

The choice fell upon the ‘protoscriniarius’ Leo. Leo, however pious and devout, was not even a priest, let alone a bishop or cardinal. His job description was:

Superintendent of the Roman public school for scribes.

A headteacher, in other words, was suddenly elevated to one of the most powerful positions in Europe. He was crowned as Leo VIII on the 6th of December.

Revenge of the Pope

The Octavianus Formerly Known as Pope John XII still had some metaphorical arrows to his imaginary quiver. From Tivoli, he schemed to launch an anti-imperial uprising in Rome.

He still had a few nobles loyal to him, and he gambled that the populace could be on his side.

But how to set off the first spark of the revolt?

According to the ever informed Liutprand of Cremona, the former pope used a network of reliable agents: his countless former lovers. Finally, some payback for all that amorous effort! On the 3rd of January 964 the supporters of Octavianus took to the streets, actively looking to assassinate Otto and ‘his’ pope, Leo.

But the emperor and his faction was just too strong, and the revolt was quickly quashed. But being distracted by the riots, Otto had failed to notice that Adalbert was on the offensive once more: he had rallied a new army and set camp in Spoleto, north of Rome.

As Otto marched north, the insurrection erupted again. The imperial garrison was repelled, and Leo VIII fled the city.

In February, Octavianus returned to Rome, claiming back the papal throne. One of his first acts was to claim vengeance on the bishops who had sided with the emperor.

Sources disagree on which bishop received which punishment, but we can gather that

A German bishop was scourged;

A Roman bishop had his nose and ears cut off;

Another bishop lost his nose, tongue, and two fingers;

And a fourth bishop had his right hand amputated.

Then, on the 26th of February, a further Council annulled all the decisions taken by the Bishops the past November. That is: Leo’s election was to be considered null and void. And obviously John was now cleared of all charges.

The reinstated pope now sat and waited for what was next: Otto’s inevitable reprisal.

He tried to appease the emperor by releasing the bishop he had flailed, but if Otto appeared to postpone an attack it was due to pragmatic, logistical problems. After defeating Berengarius and Adalbert, the emperor needed reinforcements from Germany to replenish his losses.

When Otto finally planned to march on Rome, a piece of news stopped him in his tracks.

John XII died on the 14th of May, 964 in Naples.

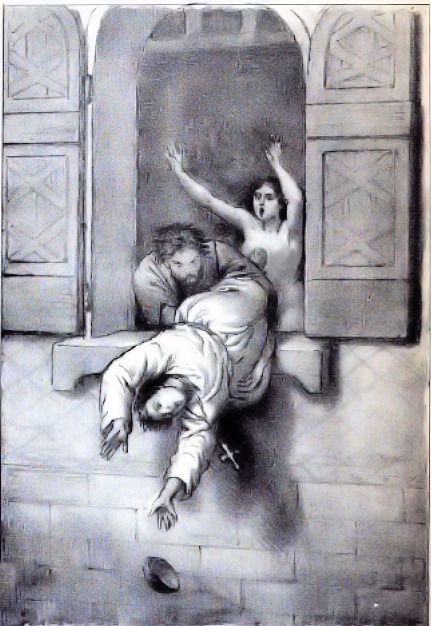

According to his harshest critic, Bishop Liutprand, the licentious young Pope had been hit by a stroke while having sex with a married lady. Stricken by paralysis, John lay in bed for eight days, until the Devil himself dealt him a blow on the temple.

According to another version, the Pope was fit as a fiddle while he frantically fornicated with his friend.

Problem is, her husband was fitter.

He burst into the room, lifted John by the neck, and tossed him from a window.

As I said: out with a bang in one way or the other.

Thus, ends the short and scandalous life of one who may have been the youngest, and worst, pope ever to be elected. The story of John XII and his legacy are frequently resurrected by contemporary commentators, as an example of how the spiritual mission of the Catholic Church can be corrupted by temporal power and hypocrisy.

As mentioned earlier, there is a strong suspicion that most of the worst crimes committed by John may have been fabricated for propaganda purposes.

He may have realistically indulged in the sins of the flesh, which was not uncommon amongst popes and high-ranking prelates in the middle ages. But allegations of murder, Devil-worship and pimping should be taken with many pinches of salt.

What I would like to draw your attention to is his political legacy.

John’s scheming and military ambitions resulted in the issuing of the Ottonian Privilege, a legal document which bound the election and the autonomy of future popes to the Holy Roman Emperors.

Moreover, as he tried to find a way out, he only succeeded in angering his once ally, thus setting a precedent for recurring Imperial interference in Italian affairs.

It took 14 popes and almost one century before the Ottonian Privilege was abolished by the Church – which only resulted in further conflict: the so-called Investiture Controversy, a political, religious, and ideological contest which degenerated in decades of revolt and civil war in Germany.

But I will stop there, before someone is tempted to blame every European war on John XII.

I will leave the final verdict to you: was he actually the worst pope in history?

SOURCES

John XII in the so-called Historia Ottonis by Liutprand of Cremona, by Paolo Chiesa, University of Udine

https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/faventia/02107570v21n1/02107570v21n1p85.pdf

The Reconstruction of the Civilization of the West, from Charlemagne (Transitio Imperii) to the Era of the Crusades

https://ia800708.us.archive.org/view_archive.php?archive=/22/items/crossref-pre-1909-scholarly-works/10.2307%252F3666435.zip&file=10.2307%252F3677939.pdf

General biographies

https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/giovanni-xii_%28Enciclopedia-dei-Papi%29/

https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/papa-giovanni-xii_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/

https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-XII

https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08426b.htm

https://time.com/4633580/young-pope-history/

1 Comment

I always thought the Borgia family was the worst the papacy could have produced, but this was illuminating. Thank you