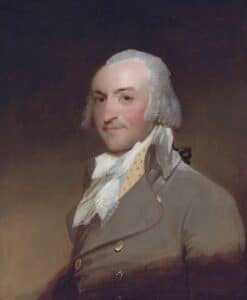

“All he touched turned to gold, and it seemed as if fortune delighted in erecting him a monument of her unerring potency.”

Those are the words of New York Mayor Philip Hone describing the business acumen of John Jacob Astor. And they were certainly accurate. It’s hard to say if Jacob Astor ever made a bad deal in his life. From musical instruments to furs to real estate, Astor knew exactly not only when to get into a business but also when to get out, and his great timing, combined with a willingness to risk it all and a good eye for bargains, turned him into one of the richest men in history.

Early Years

John Jacob Astor was born Johann Jakob Astor on July 17, 1763, in the German town of Walldorf, which was then part of the Holy Roman Empire. He was the youngest of four sons of Johann Jakob Astor Sr. and Maria Magdalena Vom Berg, although his mother passed away just a few years after his birth.

The senior Astor was a butcher by trade, and he originally intended for Jacob’s older sibling, Heinrich, to follow in the family business. Heinrich, however, didn’t want to spend the rest of his life in the same small town where he was born, so when the Prince of Hesse began recruiting soldiers to help Great Britain fight the colonies in the American War of Independence, he signed up and sailed to America in 1776.

The oldest brother, George Peter, had already left for London by that point, where he worked for a company that manufactured musical instruments. The third brother, John Melchior, also rebuffed the idea of becoming a butcher and disappeared from Walldorf abruptly, and that just left 13-year-old Jacob alone to assist his father.

Unfortunately, Jacob had a contemptuous relationship with his father, particularly after the latter decided to remarry. It wasn’t unusual for Jacob to disappear for days at a time, preferring to sleep in a neighbor’s barn than at home with his father and stepmother. For now, he was too young to do anything about it, but it didn’t look like Jacob would take up his father’s butcher trade, either.

During these unhappy years, one of Jacob’s greatest consolations was the letters he received from Heinrich in America. He filled Jacob’s head with notions of a land of freedom, without any kings or nobles, where every man had as good a chance as any other of making it big if they worked hard for it. It almost seemed too good to be true, but it completely fascinated Jacob, and he resolved that one day, he, too, would make it to America.

But then he received letters from his other brother, George, who asked why sail across the Atlantic Ocean for a better life when London was much closer. It was also a hell of a lot cheaper to get there, too. That Jacob would leave Walldorf was certain, but the question was where to go. Should he be practical and sensible and join his brother George in London or should he aim for the stars and find some way of sailing across the Atlantic to America?

Ultimately, it was Heinrich who persuaded him to put off his transatlantic trip for the time being. Although Heinrich wanted his younger brother to join him in America, he advised him that it would be better if he learned English first because “these people are very stupid at languages.” His words, not ours. So on a warm Spring day in 1779, John Jacob Astor put some money in his pockets, slung a bundle of clothes over his shoulder, said goodbye to his family, and left for England.

Once he reached London, Jacob worked alongside his brother, George, for the Astor & Broadwood Company, manufacturing flutes and pianos. The Astor name in “Astor & Broadwood” belonged to Jacob’s uncle, one of his father’s brothers who had also yearned for life in the big city. Both his uncle and older brother were kind to Jacob and encouraged him to stay in London permanently, but his main goal was still to reach America.

For this, Astor needed two things: to learn to speak English and to save enough money for the trip across the Atlantic. The first one was easy. After about six weeks of living and working in London, Astor had a good grasp of English. The second, however, was a lot more difficult and time-consuming. Even though Jacob was a hard worker and lived frugally, he was young, untrained, and inexperienced, so he was getting paid peanuts. Plus, London was an expensive place to live in, especially compared to a quiet little German hamlet.

Ultimately, it took Astor four years to save enough money, but the timing worked out beautifully since he was ready to leave soon after the newly independent America won the Revolutionary War. And so, in November 1783, John Jacob Astor packed up his belongings and once again set sail for a brave new world. His destination – New York City.

Coming to America

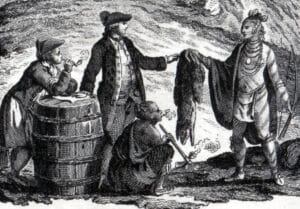

When Astor left England for America, he had $75 saved up. A third of that he paid to secure the cheapest passage available aboard a ship that was sailing to Baltimore, where he slept in steerage and ate the same hard-tack and salt-horse as the crew. Another third he kept as ready cash, and the final $25 he used to buy seven flutes from his former place of employment to sell in the new world. That was to be John Jacob Astor’s first business investment, but already he was getting new ideas thanks to a friend he made aboard the ship. It was another young German man with an enterprising spirit akin to that of Astor. He had already made the trip to America once, where he was an independent fur trader with the Native Americans. Once he had raised enough money, he bought all the furs and hides he could afford, took them to England where he sold them for a tidy profit, and now was heading back to repeat the process.

Astor made good use of the months spent sailing the Atlantic by learning all he could about the fur trade from his German friend: what each skin was worth, how to preserve and transport them, who were the best buyers and sellers in New York and London, how to deal with the Native Americans etc. Astor was a complete fish out of water, but he eagerly lapped up all the new information on the chance that it might one day prove useful.

Toward the end of January 1784, the ship reached the Chesapeake Bay. But the bay was packed with ice, and there wasn’t enough room to make it all the way to Baltimore. There was no choice other than to wait a couple more months until the ice broke. Well, some of the richer passengers opted to disembark on the ice and travel by coach to Baltimore, but this option was out of Astor’s price range, so he patiently waited and reached his destination in March. But although he was now finally on American soil, his journey still wasn’t finished. He was in Baltimore, and his brother waited for him in New York. So one more coach ride awaited him, although he was accompanied on the trip by his fur trading friend.

By the time he reached the Big Apple, Astor was down to his last shillings. Fortunately for him, once he was in New York, there was no threat of him going hungry or sleeping on the streets. His older brother, Heinrich (who now went by Henry), welcomed him with open arms and a big grin on his face.

There was one problem, though – since his arrival in America, Henry had become a butcher like his father. Of the four siblings, he was always the one most inclined to follow in the family trade, just not in Walldorf. And he loved his job, worked hard at it, and saw his business thrive. But Jacob did not go through all that effort, spend all that money, and travel all that distance to reach the land of opportunity just to get the same opportunity he had back home. Although his brother offered him a position as a clerk with a good salary, better than anyone else would give him, Jacob was willing to work anywhere except for a butcher’s shop.

Henry took no offense to this. He even found Jacob another job as a helper for a baker named George Diederich. Astor was paid a pittance for the work. His remuneration came mainly in the form of room and board, but, nevertheless, his job as an apprentice baker turned out to be one of the most important things to happen in his life. Just a few doors down from the Diederich house lived a widow named Sarah Todd who had a daughter of the same name a few years younger than Astor. The junior Sarah Todd and John Jacob Astor got acquainted, fell in love, and got married in 1785. They stayed married for five decades and had eight children together.

Getting back to Astor’s career, his position at the bakery was always intended to be temporary until he got settled in and found something better. He was still interested in the fur trade, so when an old Quaker fur merchant named Robert Browne offered him a job as a clerk with room, board, and a higher salary, he jumped at the opportunity.

Astor displayed an enthusiasm for his new job he didn’t have back at the bakery, and it was soon rewarded when Browne showed enough trust in his new employee to send him on his own to buy skins from local farmers. This was where Astor put the knowledge he had obtained during his transatlantic voyage to good use, and he did such a great job that, during the following spring, Browne sent him up the Hudson River into Iroquois territory to buy from the Native Americans. After that, Astor even went to Montreal, the biggest fur market in North America.

After just one year of working for Browne, John Jacob Astor had become well acquainted with the fur trade. But even though Robert Browne was a fair and kind employer, Astor was never going to strike it rich working for someone else. So, the next natural step was to go into business for himself.

Music First, Fur Later

By 1786, Astor had around $500 to start his venture. About half of that came from his savings and the other half from his wife’s dowry. But Astor’s first business was not what you would expect it to be. Here is the advertisement announcing its launch in the May 22, 1786, edition of the New York Packet:

“Jacob Astor, No. 81 Queen Street, Two doors from the Friends’ Meeting House, has just imported from London an elegant assortment of musical instruments, such as Piano Fortes, spinnets, guitars; the best of violins, German Flutes, clarinets, hautboys, fifes; the best Roman violin strings and all other kinds of strings; music boxes and paper, and every other article in the musical line, which he will dispose of for very low terms of cash.”

This was the first venture that launched the Astor business empire – a musical instruments shop. Remember those seven flutes Astor brought to America? He left them with the printer of the New York Packet, who agreed to display them in the window and sell them on commission. Presumably, they fetched a good price if Astor decided to expand his inventory. Obviously, having his uncle’s company back in London as a supplier played a hand in his decision, as well, especially since his uncle agreed to provide him with stock on long-term credit.

That’s not to say that Astor was giving up on his entry into the fur trade. He simply needed more time to build up his inventory, and, with the help of his wife, Astor was confident that he could grow both businesses at the same time. Sarah minded the music shop while Astor went out to secure new stock. No trade was too small for him. Astor understood that every farmboy in the land did a bit of hunting on the side and occasionally had a pelt to sell, and he wanted to become known as the man who would offer them a fair price for it. Other times, Astor loaded up his pack with all sorts of trinkets, toys, cakes, tools, and cheap jewelry and went to trade with the Native Americans. They liked doing business with him because Astor did (or, at least, attempted) something that almost no other merchant thought to do – learn their language. Then, for the large orders, Astor took all the money he made from these trades and traveled to Montreal to buy in bulk. He also did this so he could send furs to London, where he would fetch the highest prices for his cargo. He couldn’t do it from New York since there was still no trade agreement between the United States and Great Britain following the Revolutionary War.

His trading trips kept him away from New York for about half the year. During that time, Sarah took care of everything back home – she did the housework, raised the children, and handled the business. It was fortunate for Astor that he found a wife who not only shared his drive and ambitions but who had the same talent for dealing with furs and pelts. Sarah knew how to beat and cure them, knew their price, and, according to Astor himself, had a better eye than him when it came to spotting quality furs.

This is how it went for a few years. Progress was slow, and profits were small, but they kept steadily increasing. In 1789, Astor made his first real estate investment, buying two lots on Bowery Lane for $625. The following year, he also purchased a bigger house to accommodate his growing family.

While we don’t know detailed accounts of his financial movements, some things suggested that the fur trade was starting to take priority over the musical instrument business for Astor. Another advertisement in the New York Packet from 1789 revealed that, by that point, he only sold pianos and no other instruments or accessories. The same ad, however, informed us that Astor paid cash for all kinds of furs and had for sale “a quantity of Canada Beavers and Beavering Coating, Raccoon Skins, and Raccoon Blankets, Muskrat Skin, etc.”

In the 1790 city directory, Jacob Astor was listed as a fur trader with no mention of his other venture. A few years later, Astor decided to get out of the music game completely and turned the business over to a man named Michael Paff. The fur trade had just presented a golden opportunity for Astor that would, ultimately, turn him into the country’s first multimillionaire.

The Fur Tycoon

In 1794, the United States and Great Britain signed the Jay Treaty, named after US Chief Justice John Jay. It resolved a lot of lingering issues between the two sides following the war related to trade and travel, and for a man like Jacob Astor, it was like mana from heaven.

For starters, he didn’t have to travel to Canada anymore just to ship cargo to London. Furthermore, as part of the treaty, Britain evacuated all the military posts designed to keep Americans out of the Great Lakes and the territory surrounding them, and this opened up a whole new world of opportunities for Astor, and he went all in on this new venture. No longer was he the solitary trader carrying knick-knacks in his pack and loading his canoe with furs. He took on a managerial role and hired agents to do the legwork for him. His shipments got bigger and bigger, to the point where he needed to charter an entire ship to transport his goods to London. Soon after that, he was hiring multiple vessels at once and, ultimately, had his own merchant ships built so he would not have to rely on others anymore.

Astor’s business grew exponentially in the years following the Jay Treaty. By the end of the century, he was worth an estimated $250,000, although you probably couldn’t tell just by looking at him. Jacob Astor was by no means a miser, but he preferred to live frugally and was amused whenever people mistook him for just some average Joe. His one great luxury was buying a nice house for his family at 223 Broadway, which later became the site of the Astor House, one of the swankiest hotels in the country.

During the early 19th century, Astor extended his trade network to a new and lucrative market – China. He expanded his inventory to include other goods that were popular with the Chinese, such as tea, but his most profitable merchandise was sandalwood. He sold it for $500 a ton in Canton, the only Chinese port where “foreign devils” were allowed to trade, better known today as Guangzhou. Later, Astor would also add opium to his stock, which wasn’t surprising. The opium trade became so popular in China that it caused two wars during the mid-19th century.

The New York-London-Canton trading triangle turned Jacob Astor into one of the wealthiest men in the United States, and he was about to become even richer thanks to a new business opportunity courtesy of Lewis & Clark. After the Louisiana Purchase, William Clark and Meriwether Louis went on a three-year-long trek to explore the new territory and to find the most practical route across the country for the purposes of commerce.

Something like that was music to Astor’s ears. He founded the American Fur Company in 1808 and later two subsidiaries, the Pacific Fur Company and the South West Company, to establish a dominant mercantile presence in the area. This move was wholly supported by US President Thomas Jefferson. At the time, Great Britain still held trading monopolies thanks to corporations such as the East India Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company, and Jefferson was eager to give them some stiff American competition. As before, Astor went all in on this new venture, investing one million dollars in capital in the American Fur Company. He even financed his own expedition a few years later similar to that of Lewis & Clark, and his men discovered the South Pass in 1812, later used by scores of settlers to pass through the Rockies. When his men reached the Pacific Coast, they built Fort Astoria in Oregon. The fort served as Astor’s regional headquarters for the fur trade and soon developed into the town of Astoria, the first United States settlement west of the Rocky Mountains.

Astor’s western expansion was going well, with just one small hiccup: the War of 1812, when the United States and Great Britain started fighting again. British troops captured his trading posts, and an embargo prevented him from doing business with London or Montreal. Even so, Astor became one of America’s biggest financial supporters alongside two Philadelphia-based businessmen, David Parish and Stephen Girard. Together, they were instrumental in helping the federal government avoid bankruptcy by funding the war effort to the tune of over $10 million.

The Landlord of New York

When Jacob Astor first arrived in New York back in 1784, the city had a population of approximately 25,000 people. It was big for the day but still with plenty of room to grow. We can’t say if Astor ever envisioned New York City becoming the metropolis it is today, but he definitely anticipated not only its development but its role as a financial and cultural center for the United States. And, of course, he also realized this meant that real estate in New York would be worth a fortune.

Ever since he started making money, Astor began buying up property in New York and outside the city limits. He preferred empty land over residential areas or places of business, and not just cultivated farmland, but also rocky terrain and even marshes. Many of his friends and financial advisors pleaded with him to stop, warning Astor that he was jeopardizing his entire fortune. But Astor ignored them all and just kept buying and buying. In 1834, even though his American Fur Company had a monopoly on the fur trade in America, Astor sold all his interests in the corporation and invested the money in more real estate. Astor rarely developed his land; instead, he preferred to lease it. When it was time to sell, he often doubled or tripled the price he originally paid.

By the time Astor sold the American Fur Company, he was in his 70s, and his son William had taken over the day-to-day handling of the Astor business empire. In fact, Astor had become so removed from the management of his ventures that, during the 1820s, he took two years-long trips to his native Germany, including extended stays in his hometown of Walldorf. He also bequeathed them $50,000 to build a poorhouse and orphanage, which they named the Astorhaus.

John Jacob Astor got to enjoy a long retirement before dying on March 29, 1848, aged 84. He was buried in Manhattan’s Trinity Church Cemetery. His wealth was estimated to be $20 million, or around one percent of the country’s entire GDP, which prompted New York Senator Nathaniel P. Tallmadge to remark: “One in every 100 dollars in this country ends up in J Astor’s hands.”