The world has an eerie fascination with serial killers. Whether it’s hearing tales of the men who process their victims through meat grinders in order to feed the remains to future victims, or stories of strange fetishes and incomprehensible desires to commit atrocities upon corpses, people can’t help but be intrigued. This dark side of the human psyche has been featured on screens big and small for decades, and there is something undeniably captivating about true crime. It doesn’t let you look away.

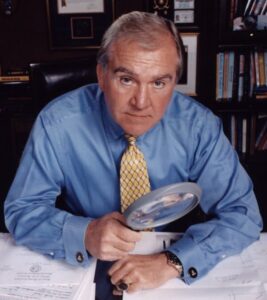

Today, we’re used to the idea of criminal profiling. It’s the science of looking at a crime and its victims in order to understand everything we can about its perpetrators. It’s easy to forget that modern Criminology is a relatively new science, pioneered by one man who joined the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 1970. Although he first started out in SWAT and later became a hostage negotiator, it was when John E Douglas finally ended up in the classroom at Quantico that he found his life’s calling. He spent much of his career investigating some of the most violent, dangerous criminals who have ever stalked and preyed upon the innocent. Douglas logged years of work interviewing dangerous men, trying to uncoil just what made them tick.

You may not recognize his name, but you certainly recognize the characters that have been based on him, and the shows inspired by his life. His story has been the inspiration for Silence of the Lambs, as well as the show Criminal Minds. A fictionalized version of him was portrayed in Netflix’s Mindhunter. Douglas really did sit down with some of the most notorious serial killers and violent offenders the country has ever seen, using what he learned from them to build the groundwork for the science of criminal profiling.

Unsurprisingly, spending years in the midst of psychotic killers is a health hazard. As you’ll find out in today’s Biographics, Douglas was fortunate to escape with his life.

Into the head of the devil

Douglas wrote the book Mindhunter: Inside the FBI’s Elite Serial Crime Unit about his experiences in the early days of behavioral analysis. The Netflix series of nearly the same name took liberties with the story, as his life was shaped into the character of Holden Ford. While there was a bit of creative license taken with the details, there was a lot of truth in the show, too — starting with his motives for deciding to interview serial killers in the first place.

Now, it’s important to note that the FBI already had a Behavioral Sciences Unit before Douglas came on the scene. It was established in 1971, and law enforcement already knew how valuable psychology could be in tracking down criminals. But here’s the thing: it wasn’t systemized. There was no manual, no set of classifications and definitions, no framework to base assessments on. When Douglas transferred there in 1977 to begin teaching hostage negotiation and applied criminal psychology, the department was still new.

And so was Douglas. On paper, he looked great. He was going into the classroom with a few years of military service behind him and seven years as a field agent under his belt, but he was still only 32 years old. And he’d seen how classrooms worked at Quantico. Instructors needed to be at the top of their game because sometimes, they were teaching the details of a case to agents and officers who had actually worked the case. And those agents didn’t hesitate to challenge an instructor if they said something even slightly wrong. Douglas realized that the fastest way to learn cases and criminals was to go right to the source. He needed to build up some serious credibility, so he started talking to some of the nation’s most infamous criminals.

Douglas began setting up interviews with the most prolific serial offenders of his time, and during that era, there were plenty of men available to him. The 1970s, 80s, and 90s would become known as a golden age of serial killers, with more than 80 percent of the 20th century’s serials cropping up during those three decades. Criminologists now believe the serial phenomenon had something to do with the coming-of-age of men who had been raised in the aftermath of World War II, an event that left broken families and broken people to raise their children.

Ted Bundy, Charles Manson, John Wayne Gacy. Ed Kemper, Richard Speck, David Berkowitz. The list is a long one, and it keeps going far past the headliners. For the public at large, each name was associated with a terrorized community, or a series of gruesome crimes; for John Douglas, each name was another corrupted mind to probe and explore.

Douglas found that what he was learning from some of the most deviant minds the bureau had ever crossed paths with could be applied to all violent crimes, not just murders. At first, he said he started conducting interviews “for survival,” but it wasn’t long before he realized the work would allow him to provide some valuable insights into future investigations.

Of course, not everyone agreed with him or his methods. His biggest detractor? The FBI.

Douglas vs. the FBI

Douglas’ exploration into the criminal mind has been undeniably invaluable, but at the time he was actively conducting interviews, the powers-that-be at the FBI didn’t see it that way. At all.

The FBI was concerned, among other things, about bureaucracy and the chain of command. Douglas was the one out in the field, traveling the country, interviewing serial killers and getting to know the local officers who were actually on the front lines of all these cases. When everyday officers needed help on open investigations, many local offices started calling him directly, instead of jumping through the hoops of a more official FBI communication channel. Douglas never wanted to turn anyone away for bureaucratic reasons, because he knew that red tape was likely to discourage agents he could quickly advise. Rather than scold officers or agents for coming straight to him, he’d help them develop a profile or advise on what information should be released to the media.

Sometimes, Douglas felt that conflict very acutely in some of the most unlikely places. One of the first big cases that the young Behavioral Science Unit consulted on was the case Netflix’s Mindhunter presents on center stage: the Atlanta child murders.

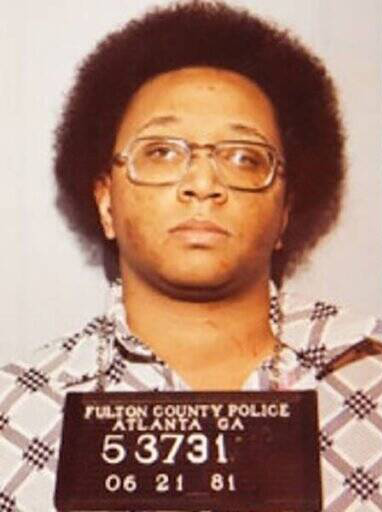

The case was real, and the killing spree began with the 1979 murders of 13-year-old Alfred Evans and 14-year-old Edward Hope Smith. Originally thought to be just another drug-related killing, it wasn’t until somewhere around 19 more children either disappeared or turned up dead that law enforcement began to connect them, finally seeing what the community had been trying to tell them all along: there was a killer on the loose.

Douglas went to Atlanta in 1981, walking the woods where bodies had been found and reviewing files. He wasn’t exactly welcomed with open arms, though. After sitting down for an FBI-sanctioned interview with People magazine — during which he said he was certain they were looking for a killer who was black — he suddenly found himself working with a field office that was less than thrilled with the effects they believed his comments were going to have.

The entire situation was a powder keg. The community had already organized an intitiative called STOP, which they did hoping to convince the Atlanta Police Department to view the killings as connected. But an undercurrent of racism and accusations that some of the local cops were card-carrying members of the Ku Klux Klan overshadowed any earnest efforts Douglas was trying to make. At the time, the black community was certain the KKK was responsible, and the idea that a white FBI agent sat down and publicly declared the killer was black just didn’t sit well with many and gave the impression that law enforcement wasn’t entirely on the side of impartial justice.

Douglas’s comments just looked bad. It was a sentiment that may have been somewhat assuaged had the FBI agents in the Atlanta field office been introduced to the media, especially Special Agent in Charge John Glover, who was the first black agent to lead a field office. There were no introductions, and instead, Douglas was told repeatedly that he was on the verge of starting a race war.

Douglas found himself fighting an uphill battle to get anyone to listen to his ideas, including applying his profile to the attendees at the Frank Sinatra and Sammy Davis Jr. benefit concert, which was organized to help fund the city’s massive manhunt. He’d hoped to get agents on board with his case theory on vetting all attendees at the concert, which would have eliminated women and suspects without a car before moving on to racial filters. Douglas hoped that process would give them a pool of suspects to investigate further, but it was never done.

Sadly, it might have helped. Wayne Williams, the man later arrested in connection with at least some of the murders, not only fit the profile, but was at the concert. Douglas long maintained Williams was the right collar for some of the cases, but he’s also remained steadfast in his belief that he wasn’t the only killer. That was based on not just his assessment of the crimes, but of patterns seen in the choice of victims.

As for Williams, he was convicted of the murder of two adults associated with the case, but the murders of the children have remained unsolved. The case was reopened in August of 2019.

The perfect interview

What is the one thing that anyone fascinated by true crime and psychology would love to do a deep dive into? The transcripts and recordings of Douglas’ interviews with people like Charles Manson and Ed Kemper, right? Here’s the thing: transcripts and tapes of most of his interviews don’t exist.

Part of Douglas’ work wasn’t just in figuring out the right questions to ask — it was figuring out how to get them to answer and how to interpret those answers. When he first began conducting his interviews, he brought along a tape recorder, but it wasn’t long before he realized that the recording was a huge mistake that was only making his subjects suspicious of him.

Douglas was already at a disadvantage going in, as a member of the law enforcement system that had arrested, tried, convicted, and sentenced them. He already represented the authority that ordered them around every day, and when he recorded conversations or tried to write them down, he found that two things happened. His subjects grew suspicious that what they were saying was going to be used against them somehow, and when he wrote, they grew angry and belligerent. They wanted his full attention, and they weren’t getting it if he was looking elsewhere.

In order to get them to talk, Douglas knew he had to create an environment that would facilitate a dialogue, and that meant he had to skip a recording device. He had to rely on memorization.

There are a few things he discovered were necessary to getting the information he wanted, and it started before he even set foot in a prison. Preparation was essential, and he would spend time going through every aspect of the cases associated with the person he was speaking to. Police reports, crime scene photos, autopsy details… it was a grisly amount of information to sift through, but it would allow him to know when the offender was being truthful and when he was lying. And they lied a lot; if he could call them out on it, though, that went a long way in establishing a relationship. It allowed him to demonstrate how well he knew their case or how closely he’d studied them. To a serial killer, that’s flattering.

After the memorization game, most everything else came down to comfort and control, but he learned that control is a tricky thing. There’s a scene that happens at least once an episode in almost every police procedural: law enforcement goes into a room where a suspect is being held and confronts them. There’s a lot of anger, some posturing, a lot of shouting, and usually a lot of accusations. That is the exact opposite of the atmosphere Douglas knew he needed to create. He always stressed that it wasn’t an interrogation, it was a conversation. Conversations go both ways, and oftentimes, that meant killers had questions for him. They asked about his job, his family… and he answered, truthfully. By answering the questions asked of him, he could create the illusion that they were the ones in control. They knew something about him, and it made them giddy.

Over the years, Douglas built up a playbook for interview techniques. He outlined how important the setup of the room was, and stressed that seating arrangements should be made based on personality. For example, he gave paranoid individuals the chance to be seated so they could always see a door or a window, and dominant personalities like Charles Manson would be given the chance to sit above him, looking down. And they usually took it.

Certain words, like “murder” and “killing” were never used. Blame was never projected, and disgust or judgement was never shown. He was always careful to keep his body language and posture relaxed and neutral, and even likened it to the sort of way one might act on a first date. There was never any negativity, but feigning empathy was sometimes a must. Sympathy for the devil, indeed.

In the end, it was often one simple thing that got many of recent history’s most notorious serial killers to open up to him: he played to their narcissism and their sense of pride in themselves and in their crimes. In short? Given the chance, many killers love to talk about themselves, especially if they have a captive audience.

The worst of the worst

For many ordinary folk, the idea of coming face-to-face with a serial killer is terrifying. But who did someone who interviewed serial killers on a regular basis rank as the worst of the worst?

For starters, Lawrence Bittaker. In 1978, Bittaker met Roy Norris at the California State Prison. They shared a morbid fantasy of kidnapping and killing teenage girls after brutally torturing them. And they did, killing five girls between the ages of 13 and 18. Douglas thought he was particularly bad because he looked so ordinary. Normal. The sort of guy these teenage hitchhikers wouldn’t have thought twice about getting in a van with. Unfortunately for them, he had nicknamed his van the “Murder Mack”.

Bittaker and Norris made auto recordings as they tortured the girls, and Douglas had the tapes. When Scott Glen was getting ready to play his fictional counterpart in Silence of the Lambs, he had the actor come to his office. He played the tapes, and says Glen’s response was emotionally charged. “John,” he said, “I was against the death penalty, but I didn’t know there are people like that.”

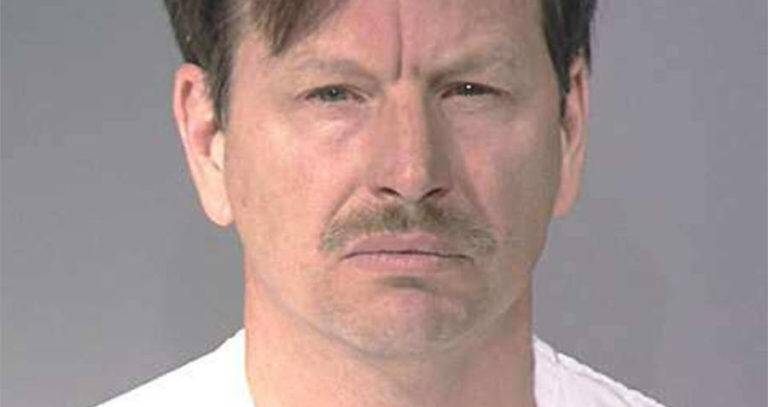

The interview that stood out to Douglas as one of the most fascinating also has a Silence of the Lambs connection, and it was the killer who was the inspiration for Buffalo Bill. Gary Heidnik was convicted in 1989, found guilty of holding women in what came to be known as Heidnik’s House of Horrors as he beat, raped, tortured, and killed them, forcing his surviving captives to help dismember the dead, then mixing the remains with dog food and feeding it to his prisoners.

Douglas has also talked about the one truly unnerving thing that all interviews have in common: the environment. He said: “…going into prisons, the doors clanging behind you. The noise level in the prisons, it’s just so loud. I don’t trust the inmates. At times, I don’t even trust corrections…”

The warning signs

As Douglas collected more information, he and his colleagues began compiling it into a centralized database called ViCAP, or the Violent Criminal Apprehension Program, and it’s worth a quick aside to mention two of those colleagues.

Douglas wasn’t working alone; he had a partner in FBI agent Robert Ressler. Ressler joined the FBI in 1970 and transferred to the BSU when it was formed. He’s the one who coined the term “serial killer”. Douglas also worked with a forensic nurse named Ann Wolbert Burgess, who started out working with the victims of sexual abuse and did some of the first formalized studies of rape cases in Boston. The FBI director at the time, William Webster, saw it as valuable information his agents needed to be trained in, and later, Burgess was brought on board to help translate what Douglas and Ressler were learning into academic terms that could be applied to other cases.

Together with a small team who Burgess remembers as not getting much resistance from the powers-that-be, simply because “it wasn’t seen as important at the time,” Douglas began to try to make sense of what they were learning from the criminals they were interviewing, and patterns began to emerge.

The first was the idea that a killer could be either organized or disorganized, essentially meaning they either planned their crimes or did not. From there, they developed a method of looking for patterns within the crimes, signatures specific to certain killers that could be used to tie murders together, and behaviors that hinted at motivation.

As he has often said, “If you want to understand the artist, look at his art.”

Douglas determined that at the heart of serial criminals of almost any kind are three words: “Manipulation. Domination. Control.” Why are these driving factors there? According to Douglas, his interviews uncovered a pattern now familiar to anyone who watches crime shows. The behavior of predators was formed in childhood, when, he said, they “all grew up without forming trusting bonds with other human beings during their formative years.”

He developed ideas regarding the questions of nature vs. nurture, too. Are serial killers born or made? He argued: “…while no one who does not have certain inborn tendencies toward impulsivity, anger, and/or sadistic perversion is going to evolve into a predator because of bad upbringing, there is no doubt in my mind that those possessing such inborn tendencies can be pushed along the path to predation by negative influences as they grow up and mature.”

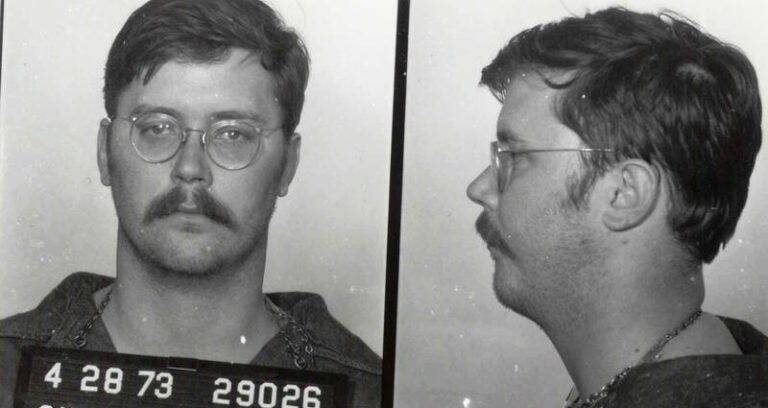

Many of these ideas are embodied in one of the most notorious serial killers that Douglas ever interviewed. When Douglas talked to Ed Kemper, he was in jail for killing his mother, her friend, and six college students. Kemper gave a full confession and showed police where to find the bodies, despite the fact that he was well-known to those police. Some called him “Big Ed,” and he liked to hang out and drink with them at a local bar.

As Douglas talked to him, he found the roots of his crimes went back into childhood. He had a terrible relationship with his abusive mother, and after being relentlessly bullied and abused by his grandparents, he killed them both when he was just 15. His history of violence went back even further, to when a 10-year-old Kemper killed the family’s cat. Kemper embodied something Douglas found in all serial predators he interviewed, and he described it as an internal conflict where feelings of self-importance, grandiosity, and superiority were constantly at war with feelings of inadequacy and inferiority. Add in a childhood full of abuse, and it’s a recipe for a killer.

And much of the time, the signs are there from childhood. Douglas described another pattern he saw, called “the homicidal triad”. It’s cruelty to animals, starting fires, and bed-wetting, a group of behaviors that can indicate something is deeply wrong. None of it, he was careful to stress, excused any of their actions as in the end. They did what they did of their own free will.

Stare long enough into the darkness…

Douglas spent almost his entire career getting inside the heads of serial offenders who have acted on some of their deepest, darkest desires, fantasies so horrible they would have made the devil blush. Did they get into his head in return? Absolutely.

In 1983, he headed to Seattle to consult on the Green River Murder case. He said goodbye to his wife at their home, then, on a hunch, he headed to the school where she was teaching and said goodbye again. By the time he hit Seattle he had a raging headache, and told the other agents he was working with that he thought he was getting the flu. That was Tuesday night, and he told them that he was taking off until Friday.

The week went by, Friday came along, and no one had heard from him. They kicked open his door — Do Not Disturb sign and all — and found him. He had collapsed, and spent three days on the floor in a coma. The official diagnosis was viral encephalitis, and post-traumatic stress disorder. He spent five months in rehab, and was told that something needed to change.

Did it? That’s debatable. Douglas oversaw an average of 1,000 cases each and every year, up until his retirement in 1995. Post-retirement, he continued to write about the cases he studied, give lectures, and work on high-profile cases like the JonBenet Ramsey case and the West Memphis Three.

The nightmares were worse when he was young. Part of that might be because of his belief that the night is the best time for quiet introspection, for going over the details of cases, crime scenes, and interviews, of dissecting everything for every last bit of information. It’s hard to turn off what he saw and heard during the day, and while it’s a vital part of being in law enforcement to become desensitized to certain sights and sounds, Douglas couldn’t allow himself to do that. Not when he was trying to learn what made them do the things they had done.

“What I do… I felt like I could not put up any kind of wall,” Douglas said. “To really understand and interpret a crime, you have to walk in the shoes of the offender as well as the victim…”

And that means visualizing everything.