James Maitland Stewart is that rare and admirable human being who could truthfully claim that everyone liked him. During his lifetime and in the years since, it was virtually impossible to find anyone recording a bad word against him, or relating an anecdote in which he appeared less than a gentleman. His distinctive drawl, coupled with his hesitant, stuttering vocal delivery made his voice instantly recognizable, and when it was heard, it was heeded. Late in his long and distinguished career, he provided the voiceover for a major soup company’s television commercials. He did not appear in the advertisements. Campbell’s reported hundreds of telephone calls to their offices, demanding to know if that was really Jimmy’s voice promoting their soup. It really was.

After all, said the American public, Jimmy Stewart didn’t stoop to doing television commercials, and how could a company afford him and not even show his face? To the public, he was always viewed that way: honest, personable, as familiar as one’s own family, as comfortable as a favorite sweater. He was Jimmy Stewart. Except that he wasn’t. He made 80 films, appeared onstage in dozens of plays, and on television in dramas, sitcoms, variety shows, and talk shows. In all of them, with one notable exception, he was credited as James Stewart. Jimmy was for friends and family, James for the public.

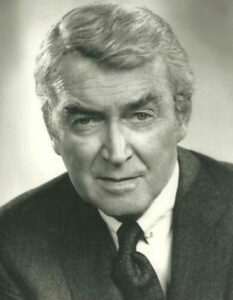

Yet the public knew him, and still knows him, as Jimmy Stewart. Perhaps that’s acceptable, since to the public, he was always much more than a remote Hollywood star. He was family; he was a friend. He was the naïve Mr. Smith, everyman, encountering the diabolical corruption of the swamp of 1930s Washington DC. He was George Bailey, the small-town banker and family man, who longed for something else. He played newspaper reporters, police detectives, musicians, aviators, the befuddled companion of an invisible rabbit, and many other roles. Yet to his public, he always came through as Jimmy Stewart, invariably honest, thoroughly decent, good to his very bones. Here is a look at the wonderful life of James Stewart.

The Hardware Store

James Stewart was born in the unusually named town of Indiana, Pennsylvania, on May 20, 1908, the firstborn to Alexander and Elizabeth Stewart. Eventually two sisters were born to the family. Alexander Stewart ran the family’s hardware store, J M Stewart and Company Hardware, which had been in the family for generations, and which Alexander hoped would one day be passed down to his own son, as had been traditional in the family. As a child, young James, who did go by Jimmy as a youth, worked in the store, attended grammar school, and taught himself to play the accordion on an instrument a customer used to square a debt. Jimmy learned that his barber played, and lessons were exchanged for odd jobs, including sweeping the barber shop. Jimmy remained a devoted accordion player for the rest of his life.

He had a paper route, and he saved his money to pay for flying lessons after the aviation bug bit him in the 1920s. He was an inattentive student at the Wilson Model School, where he attended elementary and junior high school. Jimmy preferred to spend his time drawing airplanes, making model airplanes after classes, and in general daydreaming. His grades were below average. His academic performance became a source of concern for his father.

Another family tradition for the Stewart’s was for males of the family to attend Princeton University. Alexander Stewart was a member of the Class of 1898. Determined that his only son would continue the tradition he enrolled Jimmy in Mercersburg Academy, a private institution, in 1923. At Mercersburg Jimmy enjoyed extracurricular activities, including running track and singing in the glee club, but to his disappointment, his spare, lanky physique proved unsuitable for football. It was at Mercersburg that Jimmy first encountered the acting bug, appearing in a production during his senior year in 1928.

That senior year came one year later than normal, Jimmy having become ill in 1927 with a severe kidney infection, brought about by scarlet fever. That same year Charles Lindbergh electrified the world with his solo transatlantic flight. Alexander Stewart dreamed of his son inheriting the family hardware store; the son preferred the beckoning career of an aviator. The father won out, and after graduating from Mercersburg in 1928, Jimmy dutifully acquiesced to family tradition and enrolled at Princeton, Class of 1932, with the intention of studying architecture. He spent his spare time at Princeton dreaming of building a relatively new form of infrastructure: airports and air freight terminals.

Despite the aspirations of his father and Stewart family tradition, the four years James Stewart spent at Princeton spelled the end of his career as a hardware merchant. Young Jimmy found he was popular at Princeton, enjoyed singing in the glee club, and joined the Charter Club. The latter was a male-only club dedicated to eating and drinking. Despite the good food in plenty Jimmy enjoyed at the club, he still failed to gain weight, and his lanky, six foot, three inch frame was easily spotted on the Princeton campus. It was also easily spotted on stage, where James Stewart found he had a decided taste for appearances. He joined the Triangle Club, an on-campus theater troupe. The Triangle Club performed student-written plays and revues, traditionally ending with an all-male kickline, in drag.

His grades at Princeton were exemplary, and upon graduation in 1932, he received a scholarship for advanced study, based on his thesis for airport design. Despite his love of all things aviation, he declined, choosing instead to turn his back on aviation, architecture, and the family store. The stage called, and Jimmy went to Cape Cod to join an intercollegiate summer stock company called the University Players. That summer of 1932 proved pivotal in his life. He performed onstage in numerous small roles and became close friends with another young actor, Henry Fonda, who was there with his wife, Margaret Sullavan. By summer’s end, Fonda and Sullavan were divorced, and Henry and Jimmy relocated to New York and Broadway. Sullavan moved to New York as well, and Stewart remained close with both halves of the estranged couple.

A Rising Star of the Stage and Screen

In New York, Stewart appeared in small roles, occasionally with Sullavan, who was a budding star. His stature ensured he was noticed by both audiences and critics, yet his tall and spare appearance was not all about him that was memorable. Unlike most actors of the period, he made no attempt to adopt foreign accents or affectations of speech as demanded by his roles, retaining his Pennsylvania drawl and simple mannerisms during his infrequent speaking parts. Gradually his roles grew more substantial; by 1934, he was cast in the lead in notable productions, often to excellent reviews from critics, but without a major hit to add to his resume.

He made his first appearance on film that summer of 1934, albeit without a cast credit, in a short comedy produced by Shemp Howard, one of the six performers who comprised, at different times, the act known as The Three Stooges. Whether Shemp used his influence to further Stewart’s career is debated, the sometime Stooge claimed he worked for the actor behind the scenes, as it were, but there is no evidence of his doing so. Stewart continued to perform in live theater, in New York and in summer stock, in diverse roles, as well as in minor roles in film.

In 1936, Jimmy appeared, billed as James Stewart, in the William Powell-Myrna Loy featured sequel to the popular The Thin Man titled After the Thin Man. Stewart earned rave reviews from critics for his performance in the film, though few saw his potential as a leading man in future roles. MGM called. Studio executives there viewed him as performing in roles similar to that he took on in After the Thin Man; important to the story but as a second-tier actor, supportive, rather than a leading man. Soon he was under contract.

Stewart found himself in numerous such roles in the late 1930s, appearing in films alongside Clark Gable, Jean Harlow, Myrna Loy, and other top-flight MGM stars. In the studio system of the day, he was assigned roles by executives, had little say over what they were, and was threatened with being fired if he were to turn them down. He appeared in upwards of seven films per year, usually as a secondary performer, though his reviews were usually laudatory. In 1937, he finally received top billing alongside Lionel Barrymore and Robert Young in the film Navy Blue and Gold, which proved a critical and box office success, though his casting as a football player went decidedly against type. He was still tall and thin, almost painfully so. He did not look like a football player.

Gradually, through several films, Stewart enhanced his credentials as a leading man in Hollywood, working opposite several of the most popular actresses in movies. Many of those actresses came to insist on Stewart working with them, among them the aforementioned Margaret Sullavan, Ginger Rogers, Myrna Loy, Carole Lombard, Jean Arthur, and others. Critics noticed him too, his reviews were uniformly good, with the notable exception of when he ill-advisedly appeared in a musical, Born to Dance. Variety magazine called his singing and dancing, “…rather painful”. The New York Times commented, “…his singing and dancing will (fortunately) never win him a song-and-dance-man classification”.

Stewart closed out the 1930s with two major box office hits, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and Destry Rides Again. In the former, Stewart demonstrated his honest everyman confronting corruption and power persona, appearing with Jean Arthur, Thomas Mitchell, and Claude Rains. Appointed to a US Senate seat by a corrupt political machine, Stewart’s Mr. Smith takes them on, supported by boy scouts, American morals, and the memory of Abe Lincoln. His performance cemented him as a major star in Hollywood, despite his gee-whiz innocence and simple-minded honesty, which in a later day would be called corny.

In Destry Rides Again, Stewart played a western hero who is anti gun, anti-violence, and prefers to be civil with everyone, including the corrupt town bosses he confronts. Despite his aversion to violence he is skilled with guns and fist, and brings the town to heel, as well as the saloon girl played by Marlene Dietrich. Destry Rides Again was filmed as a comedy, and Stewart’s portrayal as the hero/antihero was well received by critics.

Stewart thus entered the 1940s as a major star, and a role he took on in 1940 placed him at the very top of the Hollywood pantheon. In The Philadelphia Story, he starred with Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant. According to critics, much of Stewart’s performance was intended as comic relief, and the role won him the Academy Award as Best Actor in a Leading Role. Stewart regarded his role in the film as being a supporting role, though he accepted the award. He sent it to his father, who displayed it in the hardware store in Indiana, Pennsylvania.

The Eligible Bachelor

As James Stewart rose in the ranks of Hollywood stars, he also gained attention as one of Hollywood’s most eligible bachelors. In a later day, he would have been called a playboy, but in 1930s Hollywood, that term was frowned upon. The studio heads protected the reputation of their stars, and created often fictional social lives for them, concerned that suspicion of immorality might negatively affect box office receipts. James Stewart was considered America’s everyman, with simple tastes, what would one day be called “family values”, honest, honorable, faithful. Nonetheless Hedda Hopper, whose gossip column was widely popular, called Stewart, “the Great American Bachelor”.

He was involved in relationships with Marlene Dietrich, Ginger Rogers, Loretta Young, Norma Shearer, Dinah Shore, and Olivia de Havilland at different times, as well as many other women, some married, some single. Reportedly he did propose marriage to Olivia de Havilland in the early 1940s, though she turned him down. On the other hand, Loretta Young wanted to settle down with Stewart, which led him to terminate their relationship. He enjoyed his status as an unattached bachelor, as well as being a noted man about town, carousing with friends including Cary Grant, Gary Cooper, Ronald Reagan, David Niven, and others. He was coy with reporters regarding his private life, allowing the studio to speak for him regarding his relationships.

Off to War

James Stewart entered military service in early 1941, months before the Japanese attacked the American fleet at Pearl Harbor. He enlisted as a private, received a commission due to his experience as an amateur pilot and his college degree, and on New Year’s Day, 1942, was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Army Air Corps. The Army took advantage of his fame to use him in training and recruiting films, as well as radio and public appearances, but for Stewart that was not enough. He insisted on combat training and duty, and he got what he wanted.

His fame was such that upon his arrival in the European Theater, the British traitor and German propagandist Lord Haw-Haw welcomed Stewart in a radio broadcast. James Stewart flew B-24 Liberator bombers on 20 combat missions over Nazi occupied Europe, earning the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal, and the French Croix de Guerre. He became deputy commander of the 2nd Bombardment Wing, rose in rank from lieutenant to full colonel, and as a leader earned the respect and devotion of his men.

On one occasion, then Major Stewart learned of an illegal keg of beer hidden in a barracks by some of the enlisted men under his command. Stewart visited the barracks, “discovered” the keg, poured himself a beer, and addressed his men. Reminding them of the seriousness of violating regulations, he expressed confidence they would dispose of the keg before it was found. He then finished his beer and left. Nothing else was said about the incident.

Stewart remained in the Army reserve post-war, transferring to the United States Air Force in 1948, and eventually flying jets, including the B-52 Stratofortress. He flew as an observer over Vietnam in the 1960s. He eventually retired as a brigadier general. After World War II, he seldom spoke of his military service or wartime experiences, other than in support of veteran’s groups or Air Force recruiting. Stewart entered military service at a time when his acting career was just reaching its peak. Post-military, he found he more or less had to start all over again.

Rebirth in the Post-War Era

In 1946, James Stewart returned to films, playing George Bailey in that year’s It’s a Wonderful Life. A Christmas classic today, it was not well received by either critics or the paying public. Stewart received some accolades for his performance, including the comment that if his wife and he “…had a son we’d want him to be just like Jimmy Stewart” as he appeared in the film. The comment came from then President of the United States Harry Truman.

Subsequent roles, such as Elwood P. Dowd in Harvey, with his invisible rabbit companion, added to his persona as an American icon, both fragile and beloved. He appeared in the role both on Broadway and its subsequent film version. As actors of his generation began to give way at the box office to a new generation, including Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift, Sal Mineo, Rod Steiger, he branched into other genres. He worked in film noir, portraying investigative reporters, detectives, baseball players, and victims, frequently in the role of the underdog seeking to right wrongs.

In 1949, James Stewart, then well into his forties, married Gloria Mclean, a widow whom he had met two years previously, at a party in which he showed up slightly drunk. Despite that inauspicious beginning, they remained married until Gloria’s death in 1994. Stewart adopted her two sons from her previous marriage, and they had twin daughters of their own in 1951. One of Stewart’s adopted sons, Ronald, died in combat in Vietnam in 1969, serving in the United States Marine Corps. More than a dozen years later Stewart discussed his son in a television interview, stating, “He wanted to be a Marine, and I…and I encouraged it”. Stewart denied his son’s death was a tragedy, calling it instead, “…a loss…a terrible, terrible loss, but tragic, no. He died for his country”. An emotional Stewart then cut off the interview.

In the 1950s, he ventured into westerns, as well as movies based on aviation, a true labor of love for the long-time pilot and air force veteran. He also worked with Alfred Hitchcock, alongside Kim Novak in Vertigo and Grace Kelly in Rear Window. In the latter film, he was confined to a wheelchair, forcing him to convey his reactions and emotions solely through his facial expressions and vocal responses. It remains one of Hitchcock’s most popular films, though Stewart was not pleased that most of the praise for the film went to the director. He appeared in a starring role in Hitchcock’s experimental film Rope in 1948. Most of the reviews for that film focused on Hitchcock’s radical production techniques; the few mentions of Stewart concurred he had been miscast.

By contrast, his performance as a small-town attorney in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula in Otto Preminger’s Anatomy of a Murder drew lavish praise from critics; The New York Times called it “…one of the finest performances of his career”.

Popular with his fellow actors and the public alike, Stewart abandoned his man-about-town persona post World War II, spending evenings at home with family, or at the home of lifelong friend Henry Fonda, where the two Hollywood stars built model airplanes or played with electric railroad displays they constructed together. During breaks on film sets, Stewart was noted for amusing himself and members of the film crew by playing his accordion until he was required for scenes.

He was reticent to discuss his private life, his family, his wartime experiences, or his views on Hollywood and his fellow stars. Yet, he remained friendly with reporters, columnists, and interviewers from the budding media of television. He did not object to being called Jimmy, yet he continued to demand his credits list him as James Stewart, in a small way separating the man from his public persona.

Television

James Stewart made several forays into television in the 1960s and 1970s, appearing on variety shows, talk shows, and in 1971 as the star of a situation comedy on NBC. He portrayed a college professor living with his adult son and the son’s family. The show was titled The Jimmy Stewart Show, the only time in his career he allowed himself to be credited with the diminutive of his name. The show lasted only one season. As his career wound down, he began to be a favorite for various awards and honorary appearances.

In 1976, he joined John Wayne, with whom he had earlier starred in the western The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. Stewart played a doctor consulted by Wayne’s character in The Shootist. By then Stewart’s hearing had deteriorated to the point that he frequently missed aural cues. The Shootist was Wayne’s last film, and is often cited as Stewart’s last as well, but in fact Stewart appeared in a few more subsequent roles in film and television. He became a favorite guest of Johnny Carson’s on The Tonight Show, and appeared, as a voiceover only, in Campbell Soup commercials as a sage grandfather. A book of his poetry became popular after Stewart appeared on The Tonight Show and read an ode to his late dog, Beau, in 1981. Stewart’s recitation, in his inimitable stammering drawl, moved host Johnny Carson to tears.

An American Icon

In the 1980s, Stewart remained in the public eye, in no small part because his longtime friend Ronald Reagan was elected President of the United States. Stewart made numerous appearances at the White House, as a guest at private functions with the First Family as well as at formal State functions. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian award. He received the Kennedy Center Honors in 1983, his long-time friend and colleague Burt Lancaster handling the introduction. That time, it was Stewart who was moved to tears.

After his wife Gloria’s death, of lung cancer in 1994, the deeply private Stewart became reclusive, seldom venturing outside of the home which they had shared since purchasing it in 1951. According to his closest friend, he spent most of his time alone in his rooms. In 1996, he declined to have the batteries in his pacemaker replaced, and the following year he suffered a pulmonary embolism, which led to his death at the age of 89. He died at his home.

More than three thousand attended his memorial service and funeral, and he was buried at Forest Lawn in Glendale, California, with full military honors. President Bill Clinton summed him up when hearing of his death as “…a great actor, a gentleman, and a patriot”. Clinton also referred to James Stewart as a “…national treasure”.

In an obituary in the Orlando Sentinel, writer Jay Boyar described Stewart as “…Stammering and sincere, almost embarrassed by his decency”. The writer also quoted Cary Grant, who had starred with Jimmy in The Philadelphia Story, and who had remained a lifelong friend. “Jimmy had the ability to talk naturally”, Grant had said. “And then, some years later Marlon (Brando) came out and did the same thing all over again – but what people forget is that Jimmy did it first”.

Such was the regard he commanded from his fellow actors, the acclaim he received from critics, and the love he enjoyed from fans. His was truly a wonderful life, wonderfully lived. As Jat Boyar wrote, “It’s not only as an actor that we cherish him, but also as an emblem of something we want to believe is within all of us”.