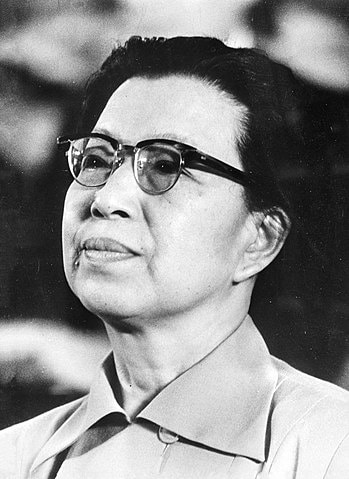

You know the saying “behind every great man is a great woman”? Well, it also applies to men who are the exact opposite of great. Jiang Qing was the fourth wife of China’s Mao Zedong, the man who oversaw one of history’s deadliest regimes. But rather than merely supporting her husband, Jiang was an active participant in his atrocities. As a key member of the Cultural Revolution Group, she dragged China into a decade of chaos that killed up to two million. She pursued spiteful vendettas, ordering the murders of people who had snubbed her decades before. At her 1980 trial, she famously described herself as Mao’s attack dog, declaring “whomever he said to bite, I bit.”

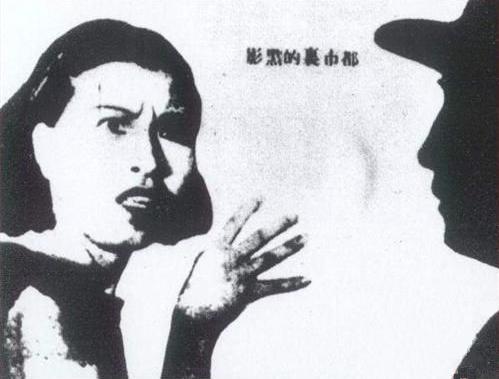

But while Jiang Qing ended her life a revolutionary psychopath, she certainly didn’t start it that way. As a young woman, Jiang had been a movie starlet. She’d had affairs, appeared in tabloids, and engaged in behavior so scandalous, the Communist Party wanted nothing to do with her. Yet, somehow, she rose to the top of that same party, ushering in an era of unparalleled chaos. Join us as we examine the life of Jiang Qing: the architect of the Cultural Revolution.

Shanghai Dreams

With just the slightest tweaking, Jiang Qing’s story could’ve been a Hollywood fairy tale. Born in March, 1914 the girl grew up in heartbreaking poverty. Her mother was a concubine, and her father a landowning drunk who seemed to be competing for the title “most-toxic purveyor of masculinity.”

He beat both women so frequently that the girl eventually snapped and – aged just 14 – ran away from home. It would be thanks to this escape that the girl discovered her true love: acting.

Incidentally, the girl wasn’t called Jiang Qing yet.

Over her life, she’d go by many names; and it’d just be luck that Jiang Qing eventually stuck. Before she became Jiang, though, the girl would live a very different life. After a year with an acting troupe, the girl signed up with the brand new Experimental Arts Academy in Shandong. Graduating in 1933, she headed straight for Shanghai.

It was almost the perfect time to be a 19-year old actress in East Asia’s Hollywood.

Just a couple of years earlier, the nationalist Kuomintang under Chiang Kai-shek had reunited China after nearly two decades of Warlord chaos. Now, with China in the throes of the Nanjing Decade, peace and prosperity had officially returned.

Well, they had for some, at least.

Shanghai in 1933 was deeply unequal. The rich were rich, the poor were destitute, and leftwing radicalism suffused the air.

Not that the girl noticed at first.

She was too focused on living out her Shanghai dreams. Although Jiang’s early years in the city were spent in minor acting groups, she was still beautiful and hedonistic enough to party with the rich and famous.

She drank like a fish, got herself swept up in scandals, chased her big break.

She was even jailed for three months for having once dated a Communist, but what did it really matter? This was all just part of her story – the tale of how one girl from a miserable background rose to become China’s greatest star.

And Jiang’s star really was rising.

In 1934, she translated a breakout role in a Henrik Ibsen play into a contract to produce films with a leftwing company. She changed her name to Lan Ping (or “Blue Apple”) and prepared to embark on her fairy tale.

But already, the cold wind of reality was beginning to seep in.

That same year, the Communists fought a 6,000km retreat from Kuomintang forces known as the Long March – both the party’s foundational myth, and the event that made Mao its undisputed leader.

It was the first sign of the radical change that would soon sweep China.

Even Blue Apple noticed. In Shanghai, she began appearing in socially-conscious films. Come 1936, Jiang was revelling in both her growing roles and her tabloid-ready love life. She had a melodramatic affair with a critic that ended with him trying to kill himself not once but twice – her first proper celebrity scandal.

But the trouble with fairy tales – even gaudy ones – is that they’re not real.

Jiang Qing may have been living a rags to riches story, but it was exactly that: a story. One that would soon prove as fake as the stagey love scenes she acted in. This was China in the 20th Century, remember?

Nobody, least of all Jiang Qing, was going to have a happy ending.

Waking Up

The phony prosperity of the Nanjing Decade abruptly ended on July 7, 1937. That was the day a skirmish between Japanese and Chinese troops at the Marco Polo Bridge snowballed into a full-blown Japanese invasion.

As the Second Sino-Japanese War erupted, Jiang fled exposed Shanghai for the wartime capital of Chongqing. Good job, too. Only a month after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, the Japanese marched on the port city, unleashing an orgy of violence.

Yet this wouldn’t be the only city Jiang Qing fled that year.

In Nationalist Chongqing, she became worried her socially-conscious, leftwing films would come back to haunt her. So she fled again, this time crossing into Communist territory.

And that was how she wound up meeting the man who’d transform Chinese history.

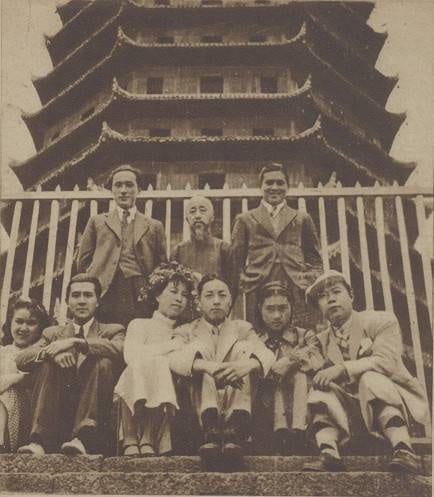

By 1937, Mao Zedong was in his mid-40s, and securely in control of the Communist movement. He was also showing signs of classic dictator egomania. When he spoke at Yan’an arts academy, he couldn’t help but be flattered by the audience member with the movie starlet looks; the one who enthusiastically applauded his every word.

Their meeting after Mao’s speech was the start of Jiang Qing’s real rise.

Not that it’d be easy. Or even particularly moral. At the time Jiang and Mao became lovers, Mao was still married to his third wife, He Zizhen, a loyal revolutionary who’d been one of the few women to survive the Long March.

She was so popular within the Communist movement that the Party tried to stop Mao seeing Jiang.

But Mao was petulant, declaring: “without Blue Apple, I cannot go on with the revolution.” At long last, and only when Jiang was pregnant, an agreement was reached. Mao could marry the actress. But he had to promise that she would never try to enter politics.

This was a big deal. The wives of most Communist leaders had very public, very powerful roles within the Party – not quite equal to their husbands, but not exactly stuck at home. But it seems the Communist higher-ups could sense Jiang’s burning ambition. Her hunger for power that was almost equal to Mao’s.

So they made Mao promise. And, unexpectedly, Mao kept that promise.

He divorced He Zizhen and had her committed to a Russian mental hospital, then married Jiang and proceeded to push her back into the shadows.

In no time at all, the sex had gone from their relationship. Mao began shacking up with young revolutionaries behind Jiang’s back; although he never divorced her.

She was too loyal. Too fawning. Never answering back, worshipping him like a God.

So Mao kept her. Even as the Japanese were defeated. Even as he turned on and destroyed the Kuomintang, and became head of the People’s Republic of China in October of 1949. But little did Mao Zedong realize that his demure little wife was using him as ruthlessly as he used others.

“Sex is engaging in the first rounds,” Jiang Qing later said of their relationship, “but what sustains interest in the long run is power.”

Via her relationship with Mao Zedong, she’d soon amass enough power to transform the face of China forever.

The Rise

The trouble with rise and fall narratives is that life is rarely that simple. Rather than shooting to the top, most people just stumble upwards and then stumble back down.

Such was the case with Jiang Qing. At least, for the “rise” part. Kept in the background by Mao and heavily medicated, it’s likely Jiang in the 1950s didn’t feel she was rising at all.

Instead, it seems she mostly felt mentally unwell.

She began to believe the colors pink and brown triggered migraines. That even the quietest house was filled with inescapable noise. Snubbed by leading Communists, she belittled and shouted at everyone who came near her; yet refused to be left alone even for a minute.

For those familiar with Mao’s past marriage, it must’ve seemed like Jiang Qing was doomed to be shipped off to her own Russian asylum in the very near future. But before you go feeling too sorry for her, we should probably take a quick look at what was happening in the rest of China.

At the end of the 1950s, Mao’s Great Leap Forward triggered probably the worst famine in human history – as villagers were corralled into communes and forced to meet impossible grain quotas. The historian Frank Dikotter estimates 45 million starved to death. For a grim comparison point, the total number of dead in the whole of WWI was around 20 million.

So, yeah. It probably kinda sucked to be Madame Mao, locked away and snubbed by your husband’s comrades, but it probably sucked significantly more to be dying in some frozen field.

Yet it would be this same famine that rescued Jiang Qing from obscurity.

By 1962, it was obvious even to Mao that his Great Leap Forward had been more like the Great Leap into Utter Catastrophe.

The atmosphere in the party was mutinous. There was open criticism of Mao. Suddenly weakened, the Chairman needed as many ultra-loyalists around as he could find, lest he be deposed.

And who was more loyal than his darling wife?

On September 29, 1962, over twenty years after they married, Mao introduced Jiang Qing to a Party conference, bringing her into the limelight.

Immediately, Jiang began amassing a powerbase.

Latching onto defense minister Lin Piao, she had herself made the army’s cultural commissar. From there, she engineered a drive to purify China’s culture, purging playwrights and opera companies that failed to produce appropriately “revolutionary” works.

At the height of her purge, she even managed to topple the Minister of Culture, a big scalp for someone so new to the game.

But then, Jiang Qing was a natural despot.

Ever since her actress days, she’d excelled at holding a grudge. And now, given free reign to attack the cultural sector, she set about harassing as many detractors as she could get away with. She even stuck the knife into her husband. One of the “revolutionary” plays she approved involved an elderly tyrant with a beautiful, young wife he fails to satisfy then kills.

Mao apparently watched the Beijing performance looking like someone had just force fed him a sackful of lemons.

But rather than turn on his newly-insolent wife, Jiang’s spirited purge seems to have given Mao an idea.

By 1965, there were dangerous rumblings that the failure of the Great Leap Forward could topple the chairman. So Mao survived the only way he knew how. Not by setting traps and ruthlessly purging like Stalin would, but by creating so much chaos, his rule would come to seem the one steady rock the nation could cling to.

He called his new project the Cultural Revolution.

And it would send China spiralling into new depths of madness.

Monsters and Demons

In February, 1965, Jiang Qing found herself returning to Shanghai – on Mao’s orders – for the first time in years.

Although she’d needled him with the play, Jiang was always fanatically loyal to her husband. When he told her to go back to the city of her acting days, she didn’t think twice. Once in Shanghai, Jiang hooked up with the party’s local director of propaganda, Zhang Chunqiao, and the acerbic writer Yao Wenyuan.

Together, they would form three quarters of China’s notorious Gang of Four.

But that was in the future. For now, the Gang of Not-Quite Four focused on setting up a secret rival to Beijing’s Ministry of Culture; just in time for Mao to purge the real thing. Mao had already chosen the cultural sphere as the next battleground. He just needed someone to first clear the decks of the Party’s old guard.

Jiang Qing happily obliged.

In February, 1966, her Shanghai unit launched a broadside against the last guardians of culture, labelling them a “black force trying to dominate our politics.”

Right on cue, the targets were denounced and purged, leaving the Shanghai unit at the forefront of propaganda. It was the start of a steady drumbeat towards anarchy. The pace first picked up in May, when the People’s Daily – a Party mouthpiece – exhorted students to turn against “cultural traitors”.

It gained speed when students in the cities responded by painting the first “big character” posters; sheets as big as a door sprayed with revolutionary calls to arms and denunciations.

Finally, it reached a gallop when Mao made his move.

On May 16, Mao authorized a secret memo targeting bourgeoisie who had “sneaked into the Communist Party, the government, the army and various spheres of culture”.

Shortly thereafter, the Cultural Revolution Group was born.

Consisting of Jiang Qing and her Gang of Four-Minus-One, plus some other ultra-loyalists, the group was allowed to operate outside of checks and balances. From their offices near the Forbidden City, they controlled propaganda; the means of communication; the machinery of state.

It was, essentially, a coup. One which kept Mao in charge, but ripped power away from anyone under him who wasn’t named Jiang Qing.

And Madame Mao was determined to use her newfound power to make her husband proud.

The opening salvo came on June 1.

That day, the Cultural Revolution Group issued an article in the People’s Daily, calling on students to “Sweep Away all Monsters and Demons!”

It singled out teachers and school masters, claiming they corrupted the young with reactionary thoughts.

That same evening, “big character” posters put up by Beijing students denouncing their teachers were read out live on radio. The next day, all schools were suspended.

It was the opening of the floodgates.

Rather than stay home, the nations’ teenagers swarmed their schools, where party cadres handed out paper and paint.

Big character posters began appearing in every classroom, upbraiding teachers and fellow students. But what to do with those who’d been denounced?

The answer came on June 13.

That day, at a televised mass trial in Beijing, images were broadcast of “counter revolutionaries” forced to confess their sins and submit before a screaming crowd of thousands.

Even girls as young as six were filmed, shrieking “kill! Kill!”

The template for the Cultural Revolution had at last been set.

Now it was time for the carnage to begin.

Chaos Reigns

That summer, 1966, China slipped into a hellish fever dream. Across June and July, the nation’s students went full Lord of the Flies.

Denounced teachers were forced to wear dunce caps, or made to crawl through school with signs saying “dog” hanging around their necks. By the middle of the month, the students had graduated to torture, forcing principals to kneel on broken glass for hours at a time.

On June 16, Chairman Mao swam across the Yangtze River to show he was ready for ideological battle. He dismantled the work teams future premier Deng Xiaoping had sent into schools to try and calm the situation.

By late July, the first deaths – from sucide, from overzealous torture – had been reported. But Mao responded simply by painting his own “big character” poster declaring “Bombard the headquarters”.

Shortly after, “big character” posters swept out of schools and across Beijing, covering every available surface. It became vital to study them every day to see if you’d been denounced.

But the real terror started on August 8.

That day – just three days after a gang of teenage girls had publicly beaten their vice principal to death – the Cultural Revolution Group announced sixteen new articles. The articles encouraged students to “to destroy “the four olds”: old customs, old culture, old habits, and old ideas.”

And, most importantly, they declared that no action would be taken against students who engaged in violence. No matter what they did.

Just like that, open season was declared.

Red August is infamous today for how quickly it devolved into anarchy. Teenagers – most of them barely fourteen or fifteen – self-organized into Red Guard units that imprisoned teachers and fellow students and killed them in grotesque ways.

People had boiling water poured over them. Others were stoned to death.

In elementary schools, children of only ten or twelve forced their teachers to swallow nails. Soon, the violence was spilling out into the streets, as teenage Red Guards began attacking the homes of anyone who looked “counter revolutionary”.

Not long after, lists of targets prepared by the Cultural Revolution Group started appearing on walls, adding to the violence. By late September, nearly 2,000 had been murdered in Beijing alone.

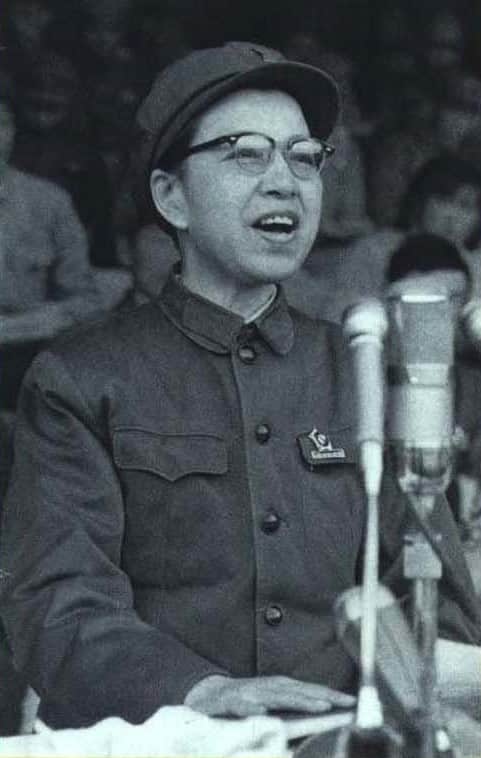

But for Jiang Qing, life was a non-stop party.

As Mao used the chaos to shore up his own position, Jiang used it to settle scores. In January of 1967, her group overthrew the local Communist Party in Shanghai, triggering a wave of uprisings, as Red Guards seized weapons from the army and turned cities into warzones.

At last united with the last member of her Gang of Four – the labour activist Wang Hongwen – Jiang became the face of the chaos gripping China.

She appeared on posters, made speeches to tens of thousands, had books dedicated to her.

In charge of cultural output, she banned all but eight operas, and wrote exacting rules on how everything from music to theatre to novels should be created. She then set about using those rules to target all those she felt had personally wronged her.

Actor Zhao Dan, who’d refused to appear opposite her onstage in the 1930s, was hounded and tortured. A script writer named Xia Yan was denounced because he hadn’t wanted to write Jiang a part decades before. A co-star named Li Lili who’d gotten better reviews for a 1936 film she and Jiang appeared in was arrested and her whole family tortured. Her husband died from the ordeal.

Nor did Jiang stop at artists.

The children of senior Communists who’d snubbed her after her marriage to Mao were murdered. The future premier, Deng Xiaoping was denounced twice and his son crippled by torture.

Even today’s Chinese president, Xi Jinping, saw his father arrested and humiliated during the upheaval.

The worst part?

Jiang Qing and the Cultural Revolution Group were just getting started.

Hell on Earth

In 1967, Mao wrote to Jiang Qing, telling her the goal of the revolution was “great disorder under heaven” that would later inspire “greater order under heaven”.

The Chairman certainly got the first part right.

A full account of all the crimes committed would probably require us starting a whole new channel called Cultural Revolutionograhics and uploading daily videos for the next five years. But we can certainly give you an overview, so you can understand how it must’ve felt to be alive at that time.

The biggest flavor of the period was a mix of insanity and extreme cruelty.

In Beijing, Red Guard units declared cats were symbols of bourgeois decadence, and set about conducting a “great cat massacre” in which thousands of strays were tortured and killed.

Out in the villages of Wuxuan, human “bad elements” were vivisected alive; their internal organs eaten by local party bosses. In Daoxian, villagers used the chaos to settle old scores; butchering the babies of enemies for having a “bad class background”.

Often, this chaos was utterly self-defeating.

In Wuhan, so many doctors were denounced that the healthcare system collapsed.

In Shaanxi, the transport networks fell apart so spectacularly that famine set in. Millions were reduced to eating mud and bark to survive.

Then there were the suicides.

Being denounced in the Cultural Revolution didn’t always mean being killed. But it did mean losing your job, being paraded through the streets, spat on by your neighbors, and humiliated in front of thousands in “struggle sessions”.

Not surprisingly, many killed themselves in the wake of this. In Hubei, 600 people committed suicide in just 6 weeks.

Overall, it’s thought that anywhere between 500,000 and 2 million died in the Cultural Revolution; with millions more tortured by self-appointed teenage revolutionaries. By its end, the education system had disintegrated; 20 percent of the population was suffering from malnutrition; productivity had collapsed; the economy was a ruin.

But it achieved its goal.

Mao Zedong was still in power, and stronger than ever.

Sadly for Jiang Qing, though, her survival wasn’t so clear cut.

In 1968, Mao began to worry that his wife was getting too powerful. He started telling people she had “great aspirations, but not an ounce of talent.”

Shortly after, the military moved into the cities to restore order. Red Guards were disarmed and sent by the millions to the countryside to “learn from the peasants”. In reality, this meant 12 million teenagers essentially becoming slaves, forced to do backbreaking labor thousands of kilometers from home.

Yet luck would ensure that Jiang Qing wasn’t thrown to the wolves alongside them.

As the anarchic phase of the Cultural Revolution wound down, the now-aging Mao anointed the general Lin Biao as his heir apparent. But when Lin was killed in plane crash, it was Jiang Qing and her Gang of Four that filled the vacuum.

Still completely in control of culture and propaganda, Jiang was now on a crazy high.

With no-one left to replace Mao, it really looked like she might become China’s next leader.

By 1974, she was even comparing herself to the legendary Wu Zetian – the only empress to directly rule Imperial China.

Sadly for Blue Apple, though, fate had other plans.

Rather than be the thing that ensured her survival, the Cultural Revolution would ensure Jiang Qing’s downfall.

Farewell, Beijing

In the end, Jiang Qing was outplayed by one man: Deng Xiaoping. Purged and rehabilitated under Mao, and then purged twice by the Cultural Revolution Group, Deng finally reappeared in public life in 1975. By now, Jiang was basically just waiting for two powerful old men to die: her husband, and the popular premier Zhou Enlai.

When Zhou obligingly kicked the bucket on January 8, 1976, Jiang swiftly purged his allies, ridding herself of the last challenges to her power.

She forbid public mourning of Zhou and, when Deng Xiaoping made a stirring speech in the premier’s memory, had him purged for the nine millionth time.

But crafty Deng had realized something Madame Mao was too arrogant to see.

The Gang of Four were hated by the military and the Party. Their power lay in their ability to whip up the mob, to get the people on their side – the same people who had loved Premier Zhou.

The same Premier Zhou whose memory Jiang had just pissed all over by arresting Deng for honoring him. On March 31, 1976, protestors appeared in Tiananmen Square, crying “Jiang the Witch.”

As she watched through binoculars, Blue Apple had them attacked and beaten with iron bars. They scattered into the night.

But the damage had been done.

Jiang had now attacked both the people’s premier and the people themselves. Never again would the Gang of Four be able to unleash anarchy on the streets.

In one fell swoop, Jiang had destroyed one of the two things keeping her alive.

The other vanished shortly after.

On September 9, 1976, Mao Zedong died at the age of 82.

Less than a month later, a Politburo meeting was called. There, the three present members of the Gang of Four were arrested. Paranoid to the end, Jiang Qing had wisely stayed away. But she was quickly tracked down and arrested by a military now looking for revenge.

As if to underscore how low opinion of the Gang of Four had fallen, news of their downfall caused such big celebrations that Beijing ran out of alcohol.

Four years later, with Deng Xiaoping now not just rehabilitated but in charge of the country, their trial began. Deng’s problem was that someone needed to draw a line under the excesses of the Mao era, as Khruschev had done with Stalin in his Secret Speech.

But Mao was both the Party’s Stalin and it’s Lenin – its source of legitimacy for ruling China. Denounce Mao and the whole edifice would come crashing down.

Deng’s response was masterful.

While admitting Mao had made mistakes – the formula he landed on was that 70% of stuff the Chairman did was good, and 30% bad – Deng shifted nearly all the blame for the many atrocities onto Blue Apple.

At her show trial, Jiang was blamed for the entire Cultural Revolution.

While she fought back, telling the assembled Communists “if I am guilty, how about you all?”, it wasn’t called a show trial for nothing.

In early 1981, Jiang Qing was sentenced to death, commuted to life in prison.

She was dragged from the court, screaming “traitors! Fascists!”, but her time was over. A decade later, in May of 1991, Jiang was reported to have hung herself in her cell. Supposedly, she left a note declaring:

“Chairman, I love you. Your student and comrade is coming to see you.”

Today, Jiang Qing’s name remains mud in China.

While Deng Xiaoping is hailed as the man who saved the economy; and her husband still lionized as a great leader – despite the whole 30% thing – Jiang is associated only with the nightmare of the Cultural Revolution.

Certainly, she deserves this. Jiang was a monster, a vindictive sociopath who helped engineered the chaos that killed maybe two million.

And yet, it’s worth remembering that she wasn’t acting alone.

Without Mao’s desperate need to cling to power, the Cultural Revolution could never have happened, no matter how vicious Jiang was. Madame Mao was the architect of a catastrophe, yes, but it was all in the service of her husband. Of a man modern China still officially deifies, even while admitting he “made mistakes”.

In the end, Jiang Qing may not have gotten her fairy tale ending.

But her thuggish husband got something like it, at least where his reputation was concerned. Sadly, in her death as in her life, it seems that the troubled young actress was only ever destined to play a supporting role.

Sources:

Britannica:https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jiang-Qing

LA Times obituary: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1991-06-05-mn-211-story.html

BBC Podcast, overview: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p025tl9m

Jiang in Shanghai: https://supchina.com/2019/04/05/the-brief-and-scandalous-film-career-of-madame-mao/

BBC podcast, Jiang’s role in the Cultural Revolution: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p03cgcnh

Cultural Revolution timeline: https://apnews.com/dbf0fd79a3d14b1c91c4d98b17704240/key-developments-chinas-1966-1976-cultural-revolution

More on the Cultural Revolution: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/11/the-cultural-revolution-50-years-on-all-you-need-to-know-about-chinas-political-convulsion

Further reading, Cultural Revolution – excellent book with great details: https://www.amazon.com/Cultural-Revolution-Peoples-History-1962_1976/dp/1632864231

Gang of Four Trial: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/mar/04/the-cultural-revolution-on-trial-alexander-cook-review-gang-of-four-china-mao

Great Leap Forward: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jan/01/china-great-famine-book-tombstone

Another brief overview: https://chineseposters.net/themes/jiangqing

Mao’s doctor: https://www.ft.com/content/df2eeb1a-69c3-11ea-800d-da70cff6e4d3

-1-1-e1678303278466-150x103.jpg)