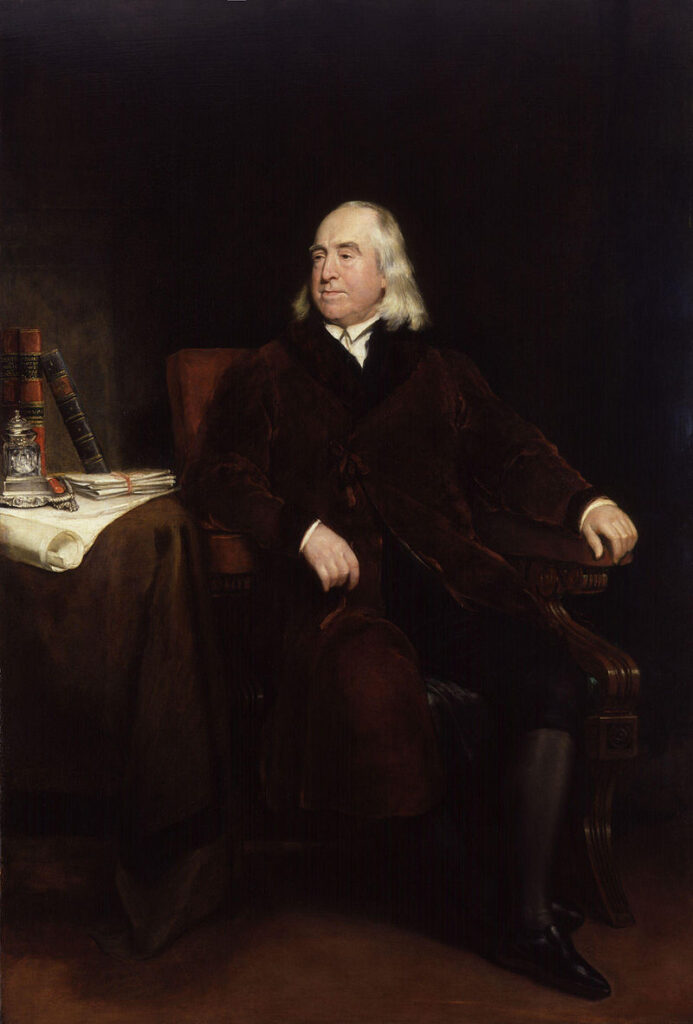

Jeremy Bentham was a man ahead of his time. Though not a philosopher, he developed a utilitarian philosophy based on the doing of good to oneself and others. He used it to propose fundamental reforms to a system that he saw as grossly unjust. His ideas have reverberated down through the ages to affect the world that we live in today. In today’s Biographix, we delve into the life and teachings of Jeremy Bentham.

A Child Prodigy

Jeremy Bentham was born On February 15th, 1748 in Houndsditch, London. The Bentham’s were a family of wealth, with income derived from an extremely successful pawnbroking enterprise in generations past. His parents, James and Alice, spent their time in social and intellectual pursuits.

Young Bentham was a child prodigy, with his extraordinary abilities becoming evident very early on. By the age of three he was reading fluently. On one occasion, when he had just turned three, he was walking in the woods with his parents and some other adults. He became bored with the adult conversation and decided to return home. As the adults were absorbed in their conversation, they didn’t notice his departure. When they returned home, the adults found him sitting at a reading desk, absorbed in reading a book on the history of England.

Jeremy’s classical studies began at the age of four. Among the journals of his father, there exists a piece of paper with the following on it . . .

The line pasted herein was written by my son, Jeremy Bentham, the 4th of December 1753, at the age of five years, nine months and nineteen days.

The line in question was a long phrase in Latin.

This document shows, not only the amazing talent of the child, but also the obvious pride that the father had in his son’s intellectual gifts. In fact, James, was constantly bragging about the genius that lay within his boy. At age four, Jeremy was learning both the Greek and Latin languages.

James employed a clerk and this man was given the duty of teaching young James to write as well as to read music and play the violin. By the age of six, a regular music tutor had been employed and James, with his miniature fiddle, became an adept violinist.

James wanted for his son to excel at everything. When Jeremy was seven, he was given dancing lessons. It was something that he absolutely detested. The boy was so weak that he was unable to support himself on his tiptoes. Yet, his father repeatedly forced him to go through the exercises, becoming more exasperated with every failed attempt.

When not absorbed in his studies with his father, Jeremy loved nothing better than to spend time at the country estates of his two grandmothers at Browning Hill and Barking. He was a lover and nature and would spend hours exploring the flowers and trees of the family grounds.

Westminster

While young James was mentally superior to his peers, physically he was anything about. He was much shorter than other children of his age and was extremely thin and weak. When he was seven years of age, he began attending Westminster School in London. He immediately hated the experience, it being a far contrast to the one on one instruction he had been receiving almost since birth. James later wrote . . .

Westminster was a wretched place for instruction. I was the least boy in the school, and the bigger boys took pleasure in pitting us one against another.

Bentham was entered into the upper second form due to his obvious advanced intellect. He soon gained a reputation as ‘the little philosopher’ as a result of his ability to reason and consider every matter. His skills in Latin and Greek made him a valuable boy to know and many of the other boys leaned on him to provide homework answers.

Bentham soon became a target for bullies at the school. However, there was one boy who served as a protector for him. If it wasn’t for this companionship, he would have been the subject of daily humiliations. In his older years he spoke with disgust at the fagging system by which the younger boys were subjected to all manner of intolerant treatment. He was just as dismissive of the teaching that was offered at the school, saying that he was taught few useful and many useless things. Bentham observed the higher the rank of a professor, the less efficient that man was.

On to Oxford

Bentham persevered with the agony and boredom of Westminster for five years. Finally, at age twelve he graduated and his father enrolled him at Queens College in Oxford. It was a remarkable achievement for a such a young man to be enrolled at university. The fact that Bentham was extremely short for a twelve-year-old made him an even greater curiosity than usual and he was stared at wherever he went.

In addition to developing an extraordinary intellectual body of knowledge, by the time he was a teenager, Bentham had also built for himself a strong moral code. He recalled . . .

I never told a lie. I never, in my remembrance, did what I knew to be a dishonest thing.

His father placed him under the care of a personal tutor by the name of Jacob Jefferson. He was a morose and gloomy person who saw it as his duty to prevent Jeremy from having anything that resembled fun. The only thing that remotely approached fun in Jeremy’s life was to play shuttlecock very irregularly. Yet, even this was unacceptable to Jefferson and he would interrupt the game and usher the boy back to his books. He instilled in Bentham’s psyche that any activity that did involve educational advancement was a waste of time.

While at Oxford, Bentham received only a modest allowance from his father. This meant that he was forced to incur debt, to his great horror. His father was also concerned that the boy was too timid and shy. On one occasion, while visiting Oxford, James took his son into the grand hall at Christ Church. At the time, the students there were all assembled for dinner. James Instructed his son to walk up and down the aisles and see if he could find any boys that he knew.

For Jeremy this was a hellish assignment. With each succeeding step he felt closer to fainting. By the time he had finished, he was red with embarrassment and had no acquaintances to report. His father, though, thought this was an excellent strategy for his son to get noticed. Further to that goal, he bought a silk gown for Jeremy, while the other boys wore plain gowns.

Bentham found the instruction at Oxford almost as pointless and uninspiring as he had at Westminster. He managed, at times, to escape the monotony of his routine with fishing, which he was not particularly fond of. He found no pleasure in the company of any other student, considering the vast majority of them to be immature morons.

When he was sixteen, Jeremy’s father took him on a tour of France. He was fascinated by the beauty and architecture of Paris, being especially impressed by the wonders of the Palace of Versailles. Shortly thereafter, his father remarried. Jeremy’s step mother, the former Mrs Abbott, had a strained relationship with Bentham and he also spoke of her with a lack of affection.

In 1766, Bentham took his master’s degree at Oxford, with a major in law. To celebrate his graduation his father gave him a gift of twenty pounds. The following year he left Oxford. In his own estimation his education at the college had not benefited him.

One of his father’s ambitions for him had failed to materialize. James had intended that Jeremy would use the opportunities at the college to establish contacts that he would be able to exploit upon graduation in order to make his way on the world. But the boy had been unable to shake his natural timidity and didn’t build any meaningful relationships with people who could help him in the future.

A New Path

Bentham was admitted to the bar in 1769, though he never ended up practicing law. He became greatly disappointed with the English legal code, which he considered to be overly cumbersome and complex. His disillusionment was compounded upon hearing a series of lectures by the leading legal authority of the time, Sir William Blackstone. After listening to Blackstone, he decided that he would no longer practice law. Instead he would write about it. He would spend his energies on critiquing the existing law and proposing ways that it could be improved upon.

Bentham took another tour of France with his father and step-mother in the latter half of 1769.

In 1770, Bentham started upon his extensive writing career. His first published works were two letters sent to the London Gazetteer when he was twenty-three. Of one of these letters he later said . . .

It was a portrait of my character and my love of fairness . . . Lord Mansfield had been attacked . . . I showed that there was no evidence for the story.

Bentham spent an inordinate amount of time perfecting every word that he committed to paper. Everything had to be precise. His early writings often contain the seeds of the ideas that were fully fleshed out in his more famous later works.

Taking on the Americans

In July, 1776, the American colonies issued their declaration of Independence. The British government did not lower themselves to issue an official response. However, a London based pamphleteer was commissioned to publish a rebuttal. The man who was charged with writing the piece was Jeremy Bentham. However, the response was not published under Bentham’s name but was the final chapter of John Lind’s Answer to the Declaration of Independence.

Bentham was a good friend of Lind and was living at his house when Lind was commissioned to the job. He was delighted to take on the Americans in print. He proceeded to pull apart the Declaration, ruthlessly exposing its weak points. He sets the tone in his introduction, declaring . . .

The opinions of the modern Americans on Government, like those of their good ancestors on witchcraft, would be too ridiculous to deserve any notice, if like them too, contemptible and extravagant as they be, they had not led to the most serious evils.

Among his many critiques, Bentham ridicules the idea of all men being created equal, stating that it gives equal status to the newborn baby and to the magistrate. He also claims that the use of Government to ensure the attainment of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness is an oxymoron – as the exercise of any form of government will alienate at least one of those inalienable rights.

Bentham dismisses the framers of the Declaration of Independence as nothing more than a mob of radicals, worse even than the German Anabaptists. He concludes with sincere wishes that these ‘ungrateful and rebellious people’ be forced back into line.

The Panopticon

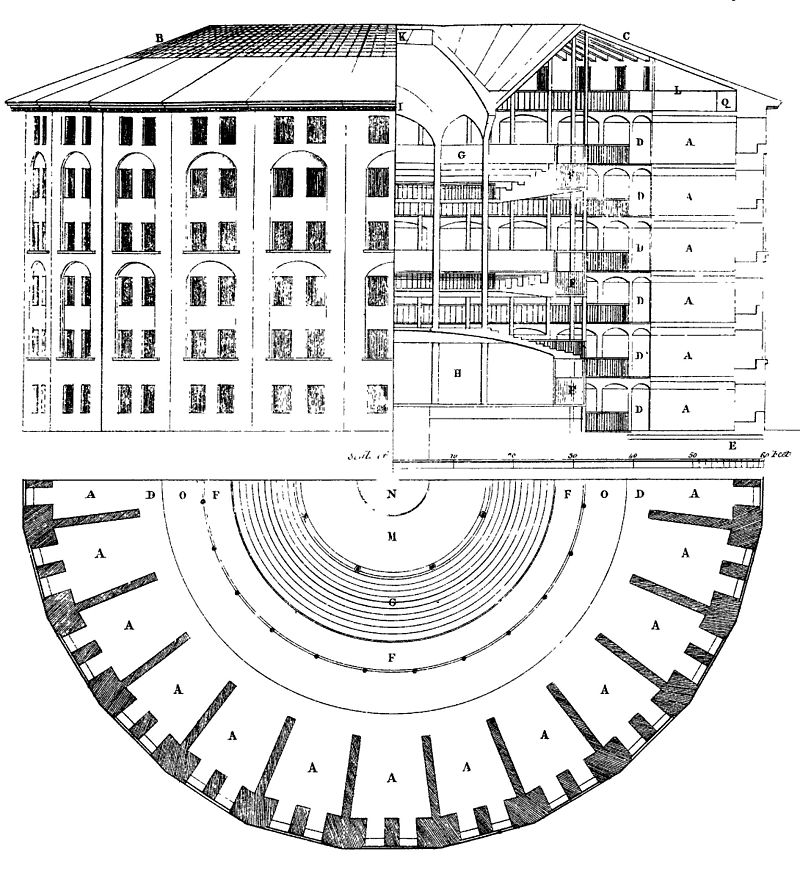

Having dismissed the Americans, Bentham set his focus on writing about social and legal reforms in his beloved England. One of his pet projects was a design for an improved prison building called the Panopticon. The design of the structure allowed every prisoner in the facility to be able to be watched by a single guard without them knowing whether or not they were under observation. Bentham was well aware that there was no way that a single watchman could actually keep an eye on everyone at the same time, but the fact that prisoners didn’t know if he was being watched would, according to Bentham, force him to regulate his own behaviour.

The Panopticon was a circular building with a watch-house in the center where a guard could monitor all of the inmates. Bentham described the design as ‘a mill for grinding rogues honest.’

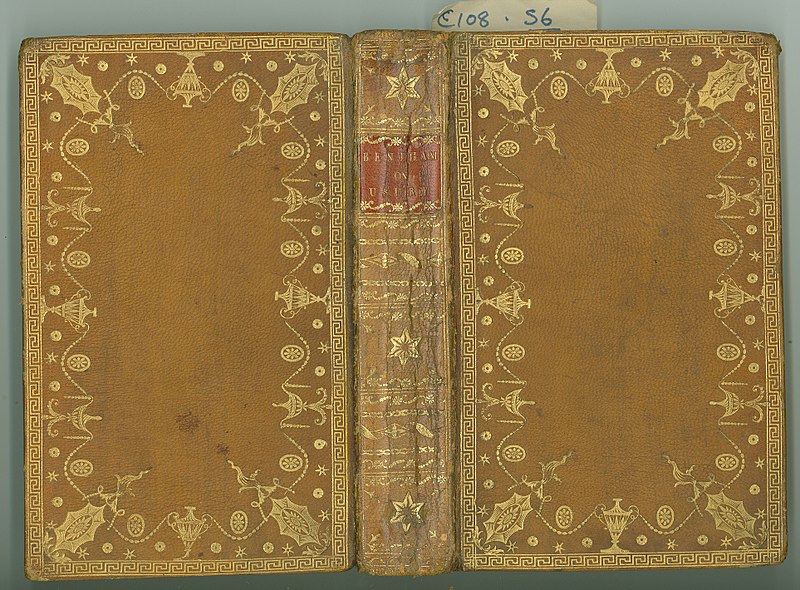

In 1791, Bentham published a book on his Panopticon plans. He fully intended for the prison to be built and even planned to govern the facility himself. In 1794 he was able to interest the government of William Pitt in the idea. He was paid £2000 for his plans. After a number of frustrating hold ups, Bentham ended up buying a plot of land on behalf of the Crown in 1799. From his perspective, the site was far from ideal. When he requested funds go buy more land, he was told to simply build a smaller prison. From this he discerned that there was no real commitment to penal reform on the part of the government. When William Pitt resigned from Parliament in 1801, enthusiasm for the project waned. Two years later it was shut down completely.

Bentham was crushed by the closing down of his pet project, stating . . .

They have murdered my best days!

Utilitarianism

Bentham’s political philosophy is summed up in the concept of utilitarianism. It is based on the principle that an action is right only if it promotes happiness and wrong if it does not promote happiness. That happiness relates not only to the instigator of an action but to the rest of society as well. Bentham’s answer to the question, what should a person do? is that a person should do only that which produces the best consequences.

Bentham was not a professional philosopher. As a critic and shaper of the law, he believed that his utilitarian principle should be the practical guide by which all people, including the lawmakers in government, made decisions. His underlying principle was summed up by his contemporary Joseph Priestly as . . .

The greatest happiness for the greatest number.

His greatest wish was that the lawmakers of society would use his principle in order to remake a more equitable and logical legal framework for society. He wrote . . .

If anything could be identified as the fundamental motivation behind the development of Classical Utilitarianism it would be the desire to see useless, corrupt laws and social practices changed.

In determining what was good and what was bad, Bentham, believed that the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain were the deciding factors. He held it as a given that pleasure was good and pain was bad. The fact that a person is rich or poor, black or white, male or female, intelligent or dim witted should, he believed have absolutely no bearing on their right to enjoy the same level of pleasure and avoid the same measure of pain as anyone else.

In the class defined society that was England at that time, this was a radical notion.

Bentham was never interested in anything unless it could be practically applied in society. In order to help people to apply his utilitarian theory he developed what he called the Hedonic Calculus. By using it, propose would be able to balance out the pleasurable and painful effects of any proposed action. The hedonic calculus includes seven factors which need to be taken into account in relation to the pleasure or pain produced when considering a course of action. These are the intensity, duration, certainty, remoteness, extent, purity and fecundity or likelihood that the sensation will be followed by more of the same.

An example of fecundity that Bentham gave was smiling at a stranger. This may make you feel good for a short period of time. But it may also cause that stranger to smile at someone else and this could keep going on indefinitely, so the sensation would be repeated many times over.

Purity is the opposite of fecundity. We might get a temporary feeling of pleasure by punching someone in the face, but the chances are high that they will punch us right back, in which case we will get the opposite sensation. So, the sensation is not pure, it is quickly diluted, so to speak.

The Pool of London

In the 1790’s, Bentham became interested in helping to clean up a notorious area known as the Pool of London. This was a stretch that rang alongside the River Thames from London Bridge down to Limehouse. It was a center of crime, vice and all sorts of illegal activity. A major problem was shipboard theft with merchants losing half a million pounds of merchandise each year.

Bentham worked with a Scottish magistrate by the name of Patrick Colquhoun for a solution to the problem. What they came out out with was the Thames River Bill, which was passed into law in the year 1800. It brought into existence the Thames River Police. This force, the first police force in England, was specifically designed to stop theft and looting from ships. It was designed to act as a preventive for crime, which was a new concept at the time.

International Influence

By the 1780’s, Bentham’s writings and influence had made him an influential world thinker. He was in contact with many people of note. He kept up a lively communication with Scottish economist Adam Smith in an attempt to bring about free-floating interest rates. He was also in communication with the movers and shakers of the French revolution. However, when things devolved into the mass terror of wholesale beheadings, he roundly criticized what was happening there.

Animal Rights Advocate

Bentham is remembered as one of the earliest advocates of animal rights. Extending his utilitarian philosophy, he stated that it was not the ability to reason, but rather the ability to feel which determined who or what was covered by the pleasure and pain principle.

Bentham did believe that animals could be killed for food or if a person was defending themselves or others from attack, but only so long as there was no gratuitous suffering involved.

Bentham was also well ahead of his time when it came to the issue of women’s rights. In fact, he once stated that it was the inequality in the treatment of women that he observed in his youth that first prompted him to take on the role of life-long reformer. Even though he was of the belief that women were both physically and intellectually weaker than men, his utilitarian philosophy prescribed that they should be able to enjoy equal rights.

The Auto Icon

As he approached his eighties, Bentham began to give serious consideration to his death and legacy. He wrote detailed directions regarding what was to be done with his corpse. In 1830, he wrote a paper in which he instructed to the English physician Thomas Southward Smith to create what he called an auto-icon and this was attached to his will.

Jeremy Bentham died on June 6th, 1832 at his home in Westminster, London. According to his instructions, his body was dissected in the presence of his friends. The auto icon was created by reconstructing the skeleton, replacing the head with a wax model, and then dressed up in his clothes and placed on a seat in a glass case. This effigy, along with the mummified head of Bentham is still on display at the University College in London.

Sources:

Timeless Books (editors): Life of Jeremy Bentham and His Correspondence

Stephen Trombley: Fifty Thinkers Who Changed the World

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeremy_Bentham