The works of James Joyce — particularly Ulysses and Finnegans Wake — are almost universally considered classics, but they’re a little different than most of the great works of literature that have been read for decades — if not centuries — in all corners of the world.

They’re notorious amongst their peers: they’re among the densest and most difficult books to try to read. They’re full of obscure language, made-up words, and pages that just dissolve into a bizarre, stream-of-consciousness narrative.

But there’s something else here that’s important, too: Ireland.

It’s not an idealized Ireland; it’s not some wonderful, bucolic landscape worthy of a postcard. Joyce captures the hardships, the poverty, and the violence suffered by so many of Dublin’s turn-of-the-century citizens. For better or worse, Joyce’s Ireland is dark and dreadful… and it’s so vivid because he wrote directly from his own experiences.

From his family’s fall from middle class to the times they escaped creditors by fleeing in the night, from his father’s drunken rages to his own realization that he had, in fact, inherited more from his father than he wanted to admit… Joyce’s works may be the most difficult in literature, but they’re also written from a place very close to reality.

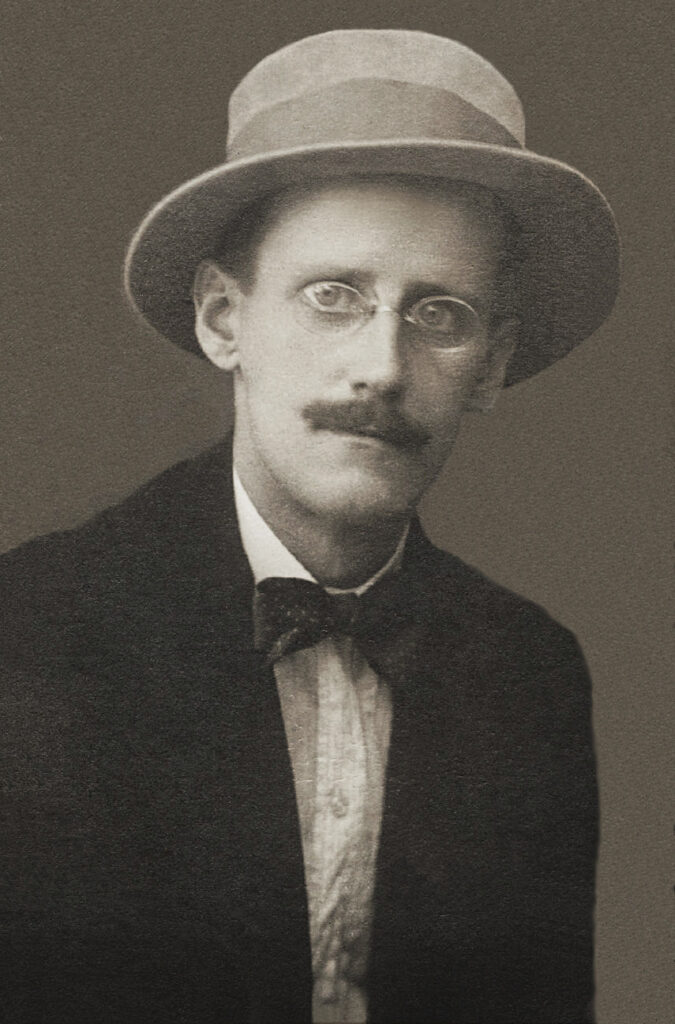

What kind of man was it that wrote some of the densest, most difficult books in the English language? One who knew the same struggles as his characters.

Write what you know… Dubliners

It’s an oft-repeated bit of wisdom that’s passed down through creative writing classes: write what you know. With that in mind, it’s only fitting that we really make an effort to capture the spirit of James Joyce and his work by starting somewhere in the middle of his story.

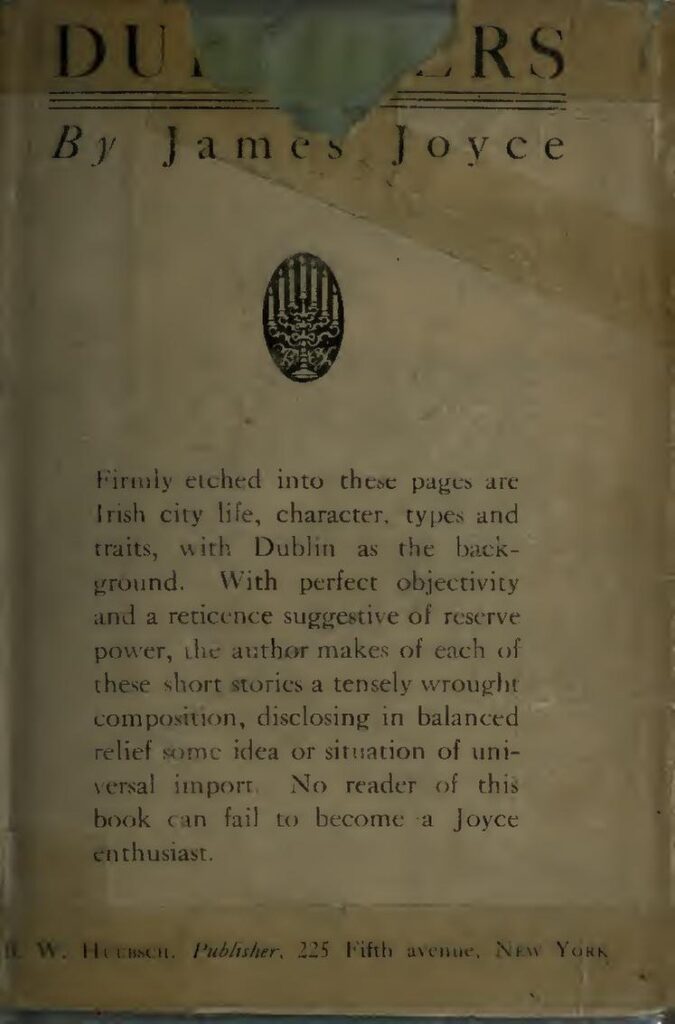

Joyce began writing Dubliners in 1904, a collection of short stories that would be published a decade later. It wasn’t an easy literary birth, either. The collection was meant to describe everyday life in Dublin with no embellishment. It was dark and dysfunctional; at the same time, it took a very moral stance about some of the issues raised in its pages. The characters deal with things like feelings of failure and despair. They earn grand opportunities, but are too terrified to seize the day, and ultimately live with regret. They spend money they don’t have on drinks they don’t need. The tome is full of betrayal, misery, worry, and unhappiness.

Joyce himself described the stories as containing a “special odor of corruption,” but when it came time to publish, that was actually a problem. The places Joyce describes are real, and most publishers were understandably hesitant to print something so dark that named real names from pubs, churches, and other neighborhood staples.

There’s another theme that runs throughout the book, and that’s one of violent parents. Fathers wonder where their sons picked up their habits of drinking and fighting, not realizing they learned them at home, while others live in such fear of their fathers that they start to suffer from the physical symptoms of constant terror.

This is where we come to Joyce himself, as his familiarity with the recurring themes of his early works explains just how much his childhood shaped his adult life. He would credit his father, John Stanislaus, with his intimate knowledge of Dublin. He also served as inspiration for numerous characters, once writing that “the humor of Ulysses is his; its people are his friends. The book is his spittin’ image.”

That’s not to say their relationship was always rose-colored. Like the pages he would eventually write, Joyce’s relationship with his father was often dark and damaged. John Stanislaus wasn’t the most reliable man — he abandoned his attempts at a medical degree in favor of his love of music. He was a well-known singer across County Cork, but that wasn’t enough for the father of May Murray, the object of his affection. They married in 1880 anyway, and right from the beginning, their lives were tinged with tragedy. Their first child died when he was only eight days old, and the second — born on February 2, 1882 — was named James Augustine Aloysius Joyce.

By the time their first surviving son was born, John Stanislaus had secured a job as a rate collector and they had settled into their first home — and, in another example of the circular nature of Joyce’s life, their address was the very same one that he would use for the titular character in Ulysses.

Joyce’s life should have been a good one. His father had a job that he took to well; they lived in a nice home, and they had a regular salary to support themselves. But their lifestyle — particularly John Stanislaus’s love of the pubs — made it difficult to make ends meet. Even as they moved into a three-story home in Rathmines and entertained some of Dublin’s most promising musicians, they were forced to take out loans and offer up property they had inherited as collateral.

Then, in 1887, John Stanislaus claimed he had been attacked in Phoenix Park, and all the cash he had collected that day was stolen. By this time, his employers were getting suspicious. He was no longer allowed the freedom he had enjoyed, and it wasn’t long after that the 6-year-old Joyce was sent away to a boarding school in Clongowes Wood College. While he wasn’t there to see the undeniable shift in his father’s moods, he did hear about it through his younger siblings — and there were quite a few of those. Joyce was the oldest of 10 children (although his mother had more pregnancies than that), and it was his brother, Stanislaus, who once told him that their father had become a man of “unreliable temper” and “vile humor”. It wasn’t until much later that Joyce learned things had gotten so bad that their mother had contemplated a divorce, which was unthinkable in Ireland at the time. They only reason she didn’t flee was that her confessor was horrified at the idea.

In the following years, the fortunes of the Joyce family continued on a downward spiral. John lost his job and was denied a full pension because of his poor employment history. As his debts mounted, he was forced to sell some of his property. The rest was seized by debt collectors.

Despite his boarding school status, Joyce was still around to see enough of his familial misfortune that it would leave a lasting mark on him. His sympathy for the plight of young children living in fear and poverty would become a regular influence on his work.

Joyce eventually left boarding school altogether, returning home to his family, which moved 9 times in 11 years. With his mother’s help, he took charge of his own schooling; eventually, he and his brother Stanislaus would attend Belvedere College, where they were admitted tuition-free. From there, it was on to University College in Dublin, where — despite his familiar impoverishment — the young Joyce quickly earned himself the nickname Sunny Jim because he was so quick to laugh.

By the time he had finished school, the situation at home was dire.

In his father’s footsteps

When Joyce graduated from University in 1902, the rest of the family was living in a home that a family friend described poorly. “The banisters were broken, the grass in the backyard was all blackened out,” they said. “There was a laundry there and a few chickens, and it was a very, very miserable home.”

Joyce’s brother Stanislaus wrote extensively on the continued downward spiral of the family. When their father was sober, he was “easy and pleasant […], reminiscent and humorous.” But when he was drunk? He was “lying and hypocritical […], a crazy drunkard.”

The large family splintered and struggled. Joyce headed off to Paris with a desire to pursue the same medical degree that his father had abandoned, albeit with no money. He skated by, earning what he could by teaching English and writing the odd article. But it wasn’t long before he was summoned back to Dublin. His mother was dying, and she wanted to see him one last time.

And here, too, is a very real snapshot in time that makes its way into Joyce’s work. Later, in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, a character denies his mother her dying wish and is consumed with guilt. Joyce had a parallel experience — when he returned to Ireland and found his mother dying of liver cancer, she asked him to take confession and Holy Communion. Joyce’s Catholic faith has lapsed long ago, and he refused. He also refused his uncle’s request to pray at his mother’s bedside. When she died, the guilt showed up later in his work.

Even as Joyce and his siblings were watching their mother die, their father was spiraling out of control. Stanislaus’ diary recorded one particularly heartbreaking incident, where John Stanislaus, drunk out of his mind, wandered into their mother’s sickroom and burst out, “I’m finished. I can’t do any more. If you can’t get well, die. Die, and be damned to you.” Joyce stepped in to head off a fight between his brother and their father, and according to the diaries his siblings kept in the following years, their relationship soured. John would often shout and scream when he was drunk, and now, he screamed about how much he hated his children, and his eldest in particular. One by one, his children left, and for the final decade of their father’s life, he lived alone in a boarding house. He died in 1931, and when his landlady cleaned out his room, all he had were some clothes… and a copy of his son’s play, Exiles.

And as for Joyce, he didn’t hate his father. In fact, after John Stanislaus died, Joyce appealed to the city of Dublin and asked that he be allowed to purchase a bench in an area near the hospital where he had passed. He was refused at the time, but his request wasn’t forgotten. In 2018, a bench was finally installed with an inscription that read: “James Joyce wished that a bench be placed here in memory of his father, John Joyce, who lived nearby and died in this place.”

My proud blue-eyes queen… I am mad with lust

Every artist needs a good muse, and Joyce met his not long after the passing of his mother. He was 22 years old, just back from Paris, and he had decided to stay in Dublin for a bit to teach and write book reviews.

It was around that time that Joyce spotted a young, redheaded girl walking down the street in Dublin. He approached her, asked her for a date, and she never showed up. He wasn’t about to be dissuaded, though, so when he asked her again… well, she did more than just show up. The mystery woman left quite an impression on Joyce — he would later describe that second first date as the day she “made me a man.”

Their first date was a day he would never forget — it was June 16, 1904, and it ultimately became the date he would later use as the setting for Ulysses.

As for the girl, her name was Nora Barnacle, and she was a Galway girl working in Dublin as a chambermaid. It was only a few months later, in October, that James and Nora left Ireland for the continent, eventually settling in Trieste, Italy. It’s often said that they eloped, but Joyce made it very clear that his parents’ oft difficult relationship had soured him on the idea of marriage.

He wrote, “my home was simply a middle-class affair ruined by spendthrift habits which I have inherited. My mother was slowly killed, I think by my father’s ill-treatment […] I cursed the system which made her a victim.”

That said, there was absolutely no doubt that he was completely devoted to Nora, and that they were passionately in love with each other for all of their days. Save for a few short trips, they were almost never apart, and even though they didn’t officially marry until 1931, there was no question that Joyce had found his muse and Nora had found the love of her life. When they left Ireland — and Joyce never truly recorded his reasons for leaving in any sort of concrete way — they boarded a ship separately to avoid chatter from his family.

Geoffrey Barker – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

As for Nora, it was an almost unfathomable risk. She wasn’t married, after all, and at the time, literally hopping onto a ship and leaving her home to travel the continent with a man would have been a major scandal. Nora was putting a lot of faith in him, too — if he had abandoned her, she would have had no way to support herself, and returning home would have been tricky.

Outside of Ireland, their life wasn’t just an easy, free-flowing romance. They first headed to Zurich, where the job Joyce was chasing fell through. From there it was off to Trieste, where some of Joyce’s inherited traits from his father reared themselves. For a time, Joyce skated through on odd jobs, carrying a ton of debt and massive loans, and drinking so much and so often that he relied on the kindness of strangers to carry him home.

Still, she gave birth to their first child, Giorgio, in 1905, and their second, Lucia, in 1907. While Joyce struggled to write and get published, she raised the children and acted as his assistant — the eye and tooth problems that would plague him for decades had already begun. So, too, had his tendency to pick moments and characters out of his life to write about.

In 1909, he headed back to Ireland for a visit. He was alone, and when a mutual acquaintance suggested that he, too, had enjoyed Nora’s company in a rather intimate way, Joyce was incensed. It was at that moment that he made it a point to visit the gravesite of one of her previous boyfriends; he would ultimately base characters in Dubliners on Nora and her dead lover.

The tragedy of Joyce’s attention to detail

James and Nora were still living in Italy at the outbreak of World War 1, and that’s when they moved, again, back to Zurich. Some years later, after the great European conflict was over, the lovers moved on to Paris. In the meantime, he had written works like Exiles, the play that would be found in his father’s boarding house room after his death, and the autobiographical A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. But he hadn’t been met with the kind of success that most writers hope for; instead, his work was greeted with something a little closer to confusion.

But in 1922 — on Joyce’s 40th birthday — he would finally publish what would become his most famous work: Ulysses. And it’s almost impossible to give Joyce his full due because he had no intentions of leaving any detail up to his imagination. Take the house at 7 Eccles Street. It’s a real house, and in one scene, his erstwhile protagonist Leopold Bloom returns home and finds he doesn’t have his key. He decides that instead of bothering his wife to come to the door, he’s going to hop the railing and get in through another door.

This is straightforward enough, and most authors would be fine with the possibility that there might be a little creative license taken with the scene. The railing might be a little too high in the real world, or the drop a little too far… but on November 2, 1921, Joyce wrote to his aunt and asked her to double-check for him to make sure it could be done. He had seen it done, but by someone young and athletic. Would his 38-year-old everyman be able to do it?

Did his aunt actually head out into the Dublin streets to check on whether or not it was possible? It’s hard to say, but it’s also the perfect example of just how committed Joyce was to capturing the streets of Dublin in a very grounded, ultra-realistic sort of way. Unfortunately for him, that dedication didn’t come without a price. Once Ulysses was published, he was hesitant to return to his home country because he was afraid of being sued for libel.

© O’Dea at Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

As soon as it rolled off the presses, the book was an instant source of controversy. Critics didn’t just argue about the worth of the text, but they argued about what the actual manuscript was supposed to say, too — there were so many edits to the text and corrections made by the printers that, even decades after Joyce’s death, no one is really sure just what version he actually wanted printed.

It’s also worth clearing up a common misconception: the book was banned in the UK, where censors decided that it made no sense whatsoever and was undeniably filthy. It stayed on the banned list until 1936, but it was never prohibited in Ireland. The movie based on the book was released in 1967 and immediately banned — a restriction that would only be lifted 33 years later.

After finishing Ulysses, Joyce put down his pen for an entire year. When he finally picked it up again, what came out on the page was just downright bizarre. He wrote Finnegans Wake between 1923 and 1939, and it’s been called things like “cryptic,”… which is putting it very mildly. Regardless of its difficulty or value, it’s impossible to deny that finishing the work consumed Joyce for much of the rest of his life. By the time Finnegans Wake was ready for print, his chronic eye troubles had degraded to the point where he was nearly blind, and he relied on Nora for constant help.

His history of medical problems — particularly with his eyes — isn’t for the squeamish. He had undergone a series of operations that had removed and reshaped parts of his eyes, and he had all his teeth removed, too. He underwent his seventh eye operation in 1925, and it left him in constant pain. Still, he was far from being able to rest: there was another threat on the horizon.

Fleeing France ahead of the advance of the Third Reich

Not long after Finnegans Wake was published, World War Two broke out. The Joyce family was already working through problems of their own — their son, Giorgio, was facing difficulties with alcohol, and their daughter was struggling, too. After her relationship with Samuel Beckett fell apart, she drifted into a steep mental decline. Lucia was in a mental health clinic when the Nazi Occupation of France was imminent, and the Joyces knew they needed to leave. They appealed to the Irish diplomat Sean Lester for help in escaping from France. So while Joyce, Nora, and their son were able to return to Zurich, Lucia was left behind and spent the war years in Vichy.

By all accounts, Joyce didn’t deal well with his daughter’s suffering. He sank into a deep depression that delayed his work, and when they were forced to leave her behind at the outbreak of war, he was devastated.

Lucia Joyce’s story is a tragic one. Treated by Carl Jung and diagnosed as schizophrenic, she was a promising young dancer when Beckett rejected her, saying he had only been trying to get close to her father, not her. Her behavior became more and more erratic, and it wasn’t long after that she hurled a chair at her mother that her brother had her committed. After the end of World War Two, she was transferred to Northampton, where she remained for the rest of her life. She died there, in 1982.

As for Joyce, his death came not long after he moved most of his family to the relative safety of Zurich. By all accounts, he was still heartbroken at the less-than-favorable reception critics and audiences gave his complex Finnegans Wake, and he was bearing that disappointment when he died, on January 13, 1941. He was having surgery for a perforated ulcer when he passed, at the age of 58.

The controversy around Joyce didn’t stop with his death. Because his death was so sudden and unexpected, there were no plans for his death, and at the time, Ireland was less than worried about properly honoring the man who would eventually become one of its most famous authors. When Nora asked the government to repatriate his remains for burial on his native soil, her request was refused. Irish diplomats in Zurich didn’t attend the funeral, and some of the telegrams sent to those diplomats wasn’t exactly sympathetic. One of them read: “Please wire details about Joyce’s death. If possible, find out if he died a Catholic.”

Chabe01 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

Nora, too, died in Zurich, in 1951, thanks to acute renal failure. She was 67 years old, and at the time of her death, it’s worth noting that she hadn’t seen her daughter since 1936, refusing to visit her in the institution they had confined her to.

Last year, in 2019, the Dublin City Council put forward a bid to do exactly what Nora had requested so many years prior: repatriate Joyce’s remains. The backlash was swift: Joyce may have written some of the most detailed accounts of Irish life that the modern literary world had ever seen, but he had repeatedly refused Irish citizenship, and actually died as a British citizen.

And that’s the ultimate irony of Joyce — one that’s been debated for a long time, and one that will continue to puzzle those who consider him one of Ireland’s finest writers. Joyce was able to create works that captured some of Ireland’s deepest, darkest truths, but he also spent much of his life unwilling to return to the homeland that gave him life and made him famous. Joyce’s story isn’t one of high literature, or the quintessential birth of a writer; it’s about the complicated relationship we have with the things, and people, that shape our lives.