An energetic man is striding around a large canvas laid on the floor, a half-burnt cigarette filter stuck to his lips. He wears jeans and a white T-shirt, despite the freezing cold in his studio — a large space with neither heating nor electricity. The man drips, flings, splashes dollops of paint, as if enraptured in a dance, taking cues from a melody to which only he can listen.

The painting that is taking shape has an abstract pattern. It looks both vaguely patterned and totally random. Is this an expression of chaos?

This painter might reply, ‘NO CHAOS, DAMN IT!’

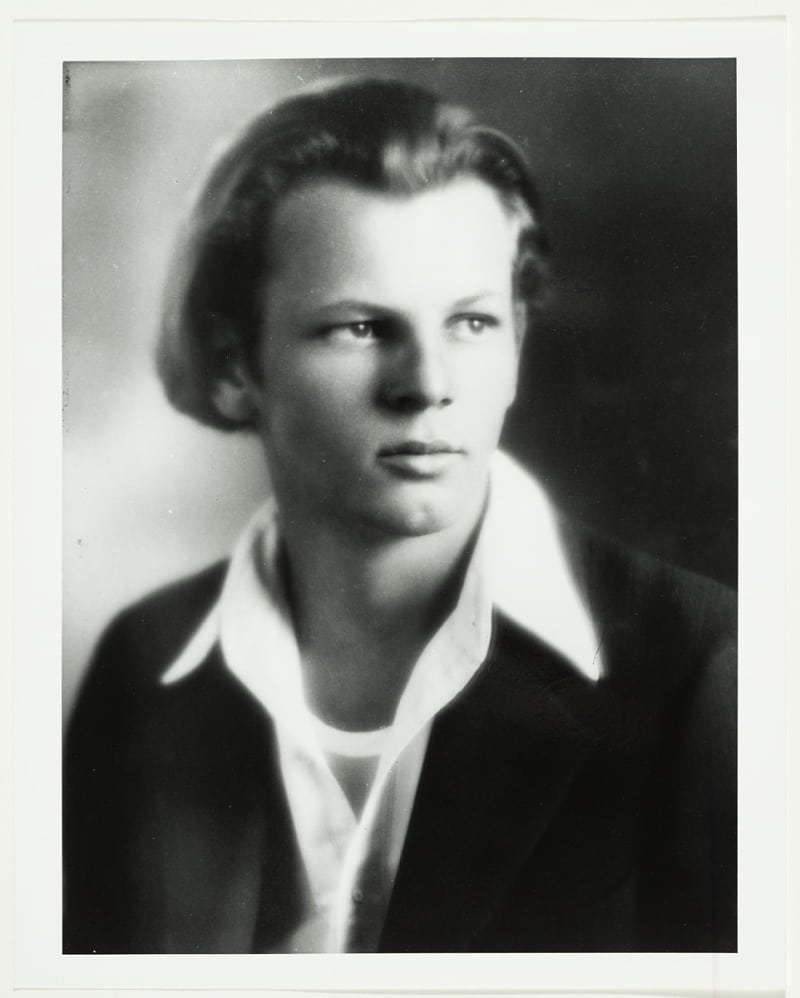

That painter was Jackson Pollock – a polarizing artist if ever there was one.

His paintings can mesmerize art lovers; they can also incite observers to shout, ‘my toddler could do it better!’

In today’s Biographics we will decode his troubled life and hermetic art – a cocktail which features Jungian psychoanalysis, fractals, and CIA involvement.

‘An Artist of Some Kind’

Paul Jackson Pollock was born on January 28, 1912, in Cody, Wyoming. The town took the name from its founder, Colonel William Cody, better known as ‘Buffalo Bill’. Pollock’s birthplace would contribute to his mythologized status as a ‘cowboy painter’ – which was, indeed, a myth. But it was one Pollock never felt the need to correct.

His parents were Stella May McClure and LeRoy Pollock. Or rather: LeRoy McCoy. But young LeRoy had lost both parents in the span of a few months, and he had been raised by his neighbours, the Pollocks.

Jackson was the youngest of five boys, all of whom Stella hoped would become artists of some kind. In her eyes, they were all potential geniuses, which suggests the image of a loving mother, proud of her children.

But the family atmosphere may have not been that rosy. A later letter written by one of the Pollock boys to his brother discusses Jackson’s emotional instability and psychological problems. In his eyes, these “date back to his childhood, to his relations with the family and our mother.”

A source of emotional instability may have been tied to a constant sense of displacement. When Jackson was 10 months old, the family relocated near San Diego. Eight months later, to Phoenix.

LeRoy was moving around the States, looking for better job opportunities, or buying and selling land. In 1917, when Jackson was five, LeRoy dragged the family back to California, this time in Chico.

All in all, during his first ten years of life, Jackson Pollock lived in six different houses across three different states.

In 1921, the oldest of the Pollock boys, Charles, moved to Los Angeles, to work at The Los Angeles Times, and to study at the Otis Art Institute. From LA, he would send back home copies of art and literary magazines, which had a great influence on his younger brothers.

The magazines also included reproductions of contemporary European art, especially of the ‘Paris School’, and especially of Pablo Picasso. This is how Jackson’s life-long obsession with the Spanish artist may have begun.

In 1923, the Pollocks moved back to Phoenix. This was another key milestone in Jackson’s formative years. In Arizona he visited Native American reservations and learned about their culture, their traditions … and, of course, their art!

In his adult years he admitted that his gestural or ‘action painting’ technique owed a debt to Native American peoples, such as the Navajo and the Mohave. Their works included abstract designs, painted on a flat area, laying on the ground. The artists used paint, sure, but also sand and other raw materials.

Jackson did not have much time to learn from these techniques, as LeRoy relocated again to California in 1924.

Three years later, the young Pollock was a freshman at the Riverside High School, near Los Angeles. And it wasn’t a nice experience.

He did not fit in, neither with the classes nor with his classmates. His father wrote to the school, concerned about the boy’s difficulties with social communication. Well, he did find a way to communicate, but it wasn’t very social: Jackson engaged in violent behaviour and was eventually expelled for fighting in March of 1928.

Jackson moved to downtown LA and enrolled in the Manual Arts High School, garnering two further expulsions and a reputation as a rebel with.. some cause. This time, it wasn’t for fighting, but for participating in student protests; inspired by his father’s socialist ideals, Jackson took every opportunity to march and protest traditional authority.

It was a pity the school had kicked him out, as he thoroughly enjoyed classes in drawing and sculpture. He was forming an identity of his future self as an artist.

In one letter to his brothers Jackson wrote:

“As to what I would like to be, it is difficult to say. An artist of some kind.”

While he figured out what kind, exactly, Jackson and his brother Sanford worked for LeRoy, employed as a topographical surveyor from 1927 to 1930. During those years, the teenage Pollock followed Leroy and his crew in surveys of the Grand Canyon, enjoying the vast landscapes of the West.

Unfortunately, he enjoyed something else.

Working with rugged, older men exposed him to alcohol at a very young age. It became a habit, then a life-long addiction. In later life, as a successful artist, he was known for becoming aggressive after a few glasses and kicking off arguments at parties, which sometimes degenerated in brawls.

At the end of the ‘Grand Canyon years,’ Jackson wrote to big brother Charles that the so-called happy years of youth had been, to him, “a bit of damnable hell.”

Guardian of a Secret

Charles was definitely a big influence on Jackson, and a trail-blazer that led him into the world of art. In 1926, Charles had moved to New York to make it as a painter. When Jackson joined him in 1930, the older brother introduced him to one of his teachers, notable artist Thomas Hart Benton.

In 1930, Jackson moved in with Charles and also became a student of Benton’s. This is the period in which Pollock’s formal training really took off, when his disparate influences coalesced, and when his style became more distinctive.

Benton introduced him to the Italian masters of the Renaissance, to Mexican muralists like Siqueiros and Rivera and to the movement he championed, American regionalism.

Pollock’s work in the mid-1930s reflects Benton’s influence.

Take the painting ‘Cotton Pickers,’ for example. The style is still clearly figurative. The subject matter deals with social injustice in a rural setting. Both elements are typical of the ‘regionalist’ style … and both are elements which formed an important stepping stone in Pollock’s career – although he would eventually break away from recognisable figures and from explicitly political themes.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Jackson Pollock was exposed to another source of profound inspiration. In attempts to fight his alcoholism, anger issues and bouts of depression, Pollock underwent psychotherapy sessions. First with Dr Joseph Henderson, from 1938 to 1941, then with Dr. Violet Staub de Laszlo in 1941 and 1942.

His therapists introduced Jackson to the methods of Carl Gustav Jung, and especially the concept of ‘Jungian unconscious’.

According to Jung, the human psyche includes three main interacting systems: the ego, the personal unconscious, and the collective unconscious.

The ego represents the conscious mind, and it comprises the thoughts, memories, and emotions we are aware of.

The personal unconscious contains forgotten information and personal repressed memories. The collective unconscious is instead shared with other members of the human species, and is made up of latent memories from our ancestral and evolutionary past.

When Pollock found it difficult to communicate his feelings to Dr Henderson, he brought along some of his sketches. A set of 83 drawings dating from this period is known as the “psychoanalytic drawings”.

They capture a transitional period in Pollock’s career: he is leaving behind his early figurative work, and shifting toward what would become his signature style, abstract expressionism. The drawings display the clear influence of Jung’s theories, as Pollock uses symbols belonging to the collective unconscious.

Symbols like the snake. According to Jung, this is a stand-in for sex, or for the baser, lower parts of human nature. In fact, snakes often appear at the bottom of Pollock’s work. At the top, one may find suns, moons and eyes, symbols of higher psychic states.

The sun disk and the moon crescent are two of Pollock’s favourites. The sun symbolises the male, conscious element of the psyche, while the moon represents femininity and the unconscious.

Pollock liked to combine the two symbols into a larger shape. According to Professor Michael Leja of Pennsylvania University, this may indicate an attempt at reconciliating the artists’ conscious and unconscious states.

Pollock’s work started to show another sign of the effect of the unconscious in the early 1940s.

This is the period in which Pollock started to incorporate paint dripping on a horizontal canvas as a preferred technique. The act of dripping paint by using brushes, sticks or even turkey basters had been influenced by Native American artists, as we have seen, but also by the Mexican painter Siquieras.

According to Michael Fried there is a further creative force at work, and that is the unconscious mind. Influenced by Jungian studies, Pollock may have given free rein to his unconscious: the apparently random lines created by paint dripping are the embodiment of pure energy, generated by repressed memories.

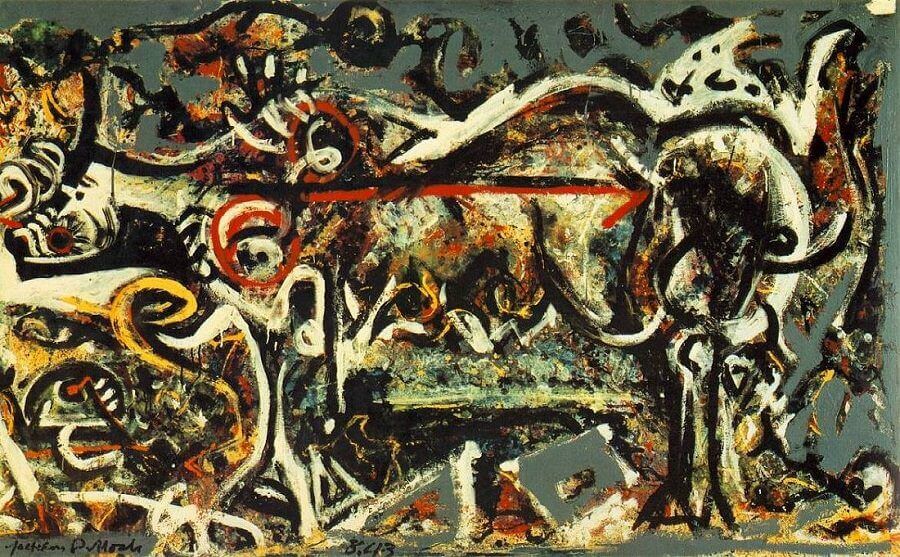

A piece of art which perfectly exemplifies Jungian unconscious at play is ‘Guardians of the Secret’, from 1943.

The canvas features a ‘painting within a painting’ — a rectangular shape, filled with abstract markings, is flanked by two figures, stylised renditions of a man and a woman. The central rectangle may be a representation of the unconscious, with its chaotic expression kept in check by the two human figures.

These figures may symbolise the ‘animus’ and the ‘anima’. Jung described these as the mirror images of our biological sex. For example, men would have an ‘anima’, their unconscious feminine side. Jung once defined the animus and anima as ‘Guardians of the Threshold’ – a definition which Pollock borrowed for the painting’s title.

‘Guardians’ was the most striking piece in Pollock’s first solo exhibition, and surely got him noticed.

Stampede

In particular, Pollock caught the eye of wealthy art collector and patron Peggy Guggenheim.

Peggy went to visit Jackson at the flat he shared in New York with his girlfriend, Lee Krasner. Lee was also a painter, who would go on to have a long and influential career.

After climbing four long flights of stairs, the exhausted Peggy found nobody home. Just when she was about to leave the building, she bumped into a drunken Jackson, back from a friend’s wedding party.

Lee and Jackson showed Peggy their respective works. The patron was mildly interested in Pollock’s and totally dismissive of Krasner’s. There may have been some jealousy at work there: Guggenheim may have developed an infatuation with Pollock and always resented Lee’s presence in his life.

Peggy walked away irritated by Pollock’s behavior, but impressed by his looks and charisma. Ultimately, it was her advisor, painter Marcel Duchamp, who convinced her to give Jackson a chance.

And so it was that in July of 1943 that Pollock received a commission to create a mural for Peggy’s new townhouse. He was free to choose the subject, but not the size: the work needed to cover an entire wall, 81 feet long and almost 20 feet high.

Pollock chose to paint with oil on canvas, rather than directly on the wall. Even so, the size of the frame was huge! His studio was divided in two rooms, none of which was large enough. Pollock ended up tearing down the partition wall.

The deadline was November 16, a date in which Guggenheim had offered to stage an exhibition of Pollock’s art. Jackson set to work immediately.

Except… he didn’t. The artist was going through a rough patch. Slipping into depression, Pollock experienced an artistic block and spent weeks staring at the empty canvas. He missed the November deadline, but shortly afterward he had a vision.

“a stampede…[of] every animal in the American West, cows and horses and antelopes and buffaloes. Everything is charging across that goddamn surface!”

Driven by this rapture, Pollock painted his ‘Mural’ in a single burst of energy around New Year’s Day of 1944. The stampede had morphed into a kinetic tsunami of abstract shapes.

‘Mural’ was recognized as a turning point for American art and it helped put Jackson on the artistic map of New York. He could count on the Guggenheim patronage, of course, but most importantly he was championed by influential art critic, Clement Greenberg:

“I took one look at it and I thought, ‘Now that’s great art,’ and I knew Jackson was the greatest painter this country had produced.”

Lucifer

In October of 1945, Jackson and Lee tied the knot, and in November, they moved to their new house, 830 Springs Fireplace Road in Springs, Long Island, New York.

Jackson converted a nearby barn into a large studio, large enough for him to lay enormous canvases on the floor. Free from the constraints of the traditional easel, the painter was able to perfect the technique for which he became famous.

The technique has become known as ‘drip painting’, ‘action painting’, or ‘gestural painting’.

By defying the convention of painting on an upright surface, Pollock added a new dimension to his creative process: he was now able to view and apply paint to his canvases from all directions.

And not just any ordinary artist’s paint. Pollock preferred household paints, varnishes, and enamels. To drip and fling these materials, Pollock used hardened brushes, sticks, and even basting syringes.

In the process of perfecting this style, Pollock moved away from figurative representation, even avoiding vague shadows of recognisable shapes.

His work ‘Lucifer’ of 1947 is a good example of this transition.

Pollock had started this painting by applying colour to the canvas in a ‘traditional’ way, but halfway through the process he went into full ‘action mode’. He dripped and spattered pigments on an underlayer, into which he had embedded small pieces of gravel, to increase the texture.

While completing Lucifer, Pollock devised another original technique. Every time he had to dip his brush into varnish, the interruption to his free movements frustrated him.

He then tried to tilt a can of household paint, allowing it to run down a stick placed at the right angle.

‘Lucifer’ and other similar works of the period debuted at the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York City in 1948.

You would think that with Greenberg behind him, the exhibition was a success, but, no … it was a critical disaster.

The wider general public in the US was simply not ready yet for Pollock’s ‘action paintings’.

Europe was a different story. Peggy Guggenheim, constantly moving between New York and Venice, took the occasion to show six of Pollock’s work at the prestigious Venice Biennale. The paintings were greatly appreciated by Italian and European critics, and so it continued the tour into Milan and Florence.

It’s worth mentioning that just a couple of years earlier, the US State Department had sponsored a touring exhibition of other American Abstract Expressionists, the same ‘school’ to which Pollock belonged.

The exhibition was called ‘Advancing American Art’.

It had the explicit intention of showcasing American abstract artists in Europe and beyond the Iron Curtain. The message was clear: the US was the home of free, open to all forms of artistic expression, as opposed to the drab, State-controlled, realist art coming from Communist Bloc countries.

Keep that in mind.

Shortly after Pollock’s European exhibitions, Jackson made it to the mainstream. On August 8, 1949, readers of LIFE Magazine got to know the painter. He appeared as a

‘brooding, puzzled-looking man’

on a two-page spread, standing in front of one of his large murals. The title of the article read

‘Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?’

NO CHAOS, DAMN IT!

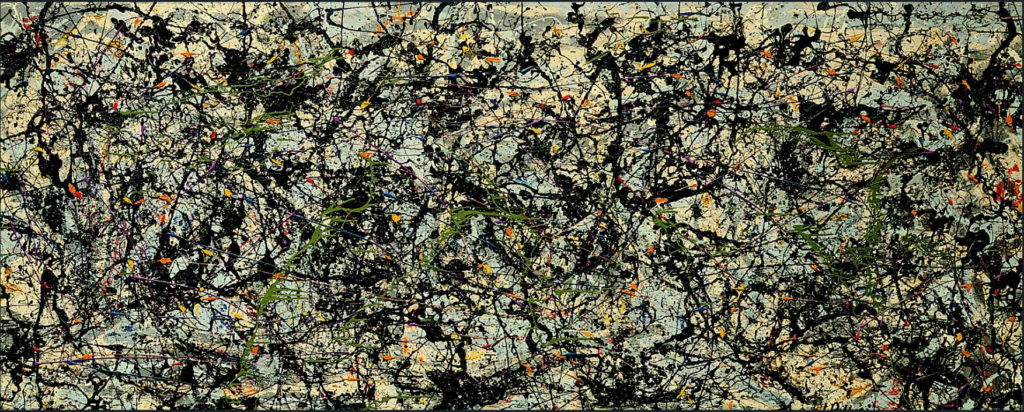

In 1949 and the early 1950s, Pollock was on a roll. This is when he produced ‘Number one’ and ‘Autumn Rhythm’, arguably the two examples in which Abstract Expressionism and action painting are at their highest power.

These large canvases lack a central point of focus. There is no hierarchy, no dominance of an element over the other; every bit of the surface is equally significant.

Pollock’s own European tour had no further motive than to advance his own art, and apparently it worked. His paintings had to establish credibility in Europe, before being appreciated at home!

Despite the wave of success and appreciation, critics were still divided. If ‘LIFE’ had Pollock’s back, TIME magazine dismissed his art as ‘chaos’.

Hence his famous reply, via telegram:

‘NO CHAOS, DAMN IT!’

Pollock firmly stated that he had a clear idea of how he wanted a particular piece to appear. More precisely, he affirmed complete control over the movements of his implements, his hands, his body.

Random forces did come into play when the paint fell over the canvas, and Pollock accepted that. The viscosity of the material, the absorption factor of the canvas, even the force of gravity. Those were the uncontrollable elements, wrestling with the controllable ones, creating a synthesis, a new meaning. Perhaps in Pollock’s mind, it was similar to how the human psyche and human behaviour are a result of conscious and unconscious factors.

Finally, Pollock regained control. As the abstract images took shape on the canvas, it was he who decided what colours or lines to add, and he would not stop until he saw what he wanted to see.

Contemporary myths depicted Jackson Pollock as a bewitched artist, high on alcohol, who randomly flung paint while ecstatically dancing to the improvisational jazz of masters like Charlie Parker.

His wife Lee Krasner later denied this. Not only did his studio lack the electricity needed to plug in a record player, but Pollock didn’t really dig those cats blurting out be-bop and cool jazz. He preferred old-fashioned, big band classics of the Dixieland era!

This myth was further dispelled by the analysis of art critics Robert Goodnought and Pepe Karmel. They studied a documentary of Pollock at work, shot by filmmaker Hans Namuth, and were able to describe Jackson’s working method in four phases.

You Can Be a Pollock, Too!

Phase 1!

Start your masterpiece by tracing some loosely representational figures.

Phase 2!

Immediately overpaint and obscure these figures. These two phases should take about two hours and leave you utterly exhausted.

Phase 3!

Take a can of black or dark enamel, dip a stubby brush and move your arm rhythmically. The paint will drip, fall and splash in a variety of movements onto the surface. Within half an hour the entire surface will be covered in weaving rhythms and patterns.

Phase 4!

Over the following two weeks you will get accustomed to the painting, returning to it to apply additional layers of colour, in a slower, and more deliberate fashion.

Goodnought and Karmel gave a good description of the process. When it came to interpreting the result, we just have to quote the much later studies published on Nature by Richard Taylor, Adam Micolich, and David Jonas.

The researchers analysed Autumn Rhythm, among other works, and realised that Pollock’s paintings presented fractal patterns.

Fractals are never-ending, infinitely complex patterns that are self-similar whether you view them from up close or from very far away. That is… the simplest definition I could find.

The trio of authors found such geometric regularity in the apparently irregular surfaces of Pollock’s masterpieces … but what was the meaning behind this?

The three main interpretations are that Pollock wanted to replicate fractals observed in nature – such as trees or coastlines; or that he wanted to represent a mathematical model of a fractal; or that the fractals observed on the canvas were simply an unintentional representation of Pollock’s movements.

In other words: the painting was merely an object, a trace left behind by the event of the artist working in his studio. And that — the event — is what is counted.

A Helping Hand

Regardless of interpretations, descriptions, and explanations, Jackson was HUGE by the 1950s. He was seen as the leader of the new vanguard of abstract expressionists.

Peggy Guggenheim and Greenberg had played their part, sure, but Pollock and his mates could count on a more powerful ally: the US Government, and the CIA.

Remember the exhibit and tour organised by the State Department in 1947? Well, it had backfired. It emerged that many Abstract Expressionists, including Pollock, were socialists or communists. This prompted the political establishment to condemn their art.

Missouri senator George Dondero declared:

“All modern art is Communistic.”

Harold Harby, a Los Angeles councilman, gave us this gem:

“Modern art is actually a means of espionage. If you know how to read them, modern paintings will disclose weak spots in US fortifications, and such crucial constructions as the Boulder Dam.”

Paintings as secret missives to the USSR about American weak points? That’s a movie I’d watch right now!

Circles within the State Department and the CIA still felt that sponsoring American Modern Art would be a good plan. The endgame was to displace Soviet social realist art from gaining traction in Europe. But they could not do it openly, now.

Conveniently, the president of the Museum of Modern Art in New York was Nelson Rockefeller, whose connections with the CIA and the diplomatic service were deep-rooted.

So, in 1952, the CIA gave MoMA a five-year grant via the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, in order to fund the “International Program.” The museum was able to organize 33 international exhibitions of abstract expressionist art across four years. With CIA money, European galleries were flooded with works by Pollock, Marc Rothko, Willem De Kooning, and similar artists.

In the same year Pollock produced ‘Convergence’, a collage of colours that created masterful shapes and lines, evoking violent emotions. A real assault on the eye, surely not very accessible. And yet, it became his best known work, thanks to the promotion granted by the ‘International program’, and to the fact that years later it was turned into a best-selling jigsaw puzzle!

But as often happens with successful, but troubled artists, the pressures of notoriety contributed to Pollock’s personal deterioration. His bouts of depression worsened. His alcoholism deepened. His behavior became more erratic. An anecdote of the time tells us how he once walked into an after-show party stark naked and urinated into a fireplace.

In 1955, Pollock painted Scent and Search, which would be his last two officially recognized paintings.

According to friend Jeffrey Potter, the following year became an abyss on non-productivity, spent by Jackson in a ‘death trance’. On a personal level, his marriage with Lee had deteriorated as well, marking twin calamities.

During a night spent drinking at his favorite bar, the ‘Cedar’, Jackson met a 26-year-old model and gallerist, the beautiful Ruth Klingman.

According to Ruth, the meeting had been coincidental. According to artist Audrey Flack, she had precise plans to seduce the top artist of the New York scene. In any case, the two began a torrid affair. Their relationship was only physical at first; soon after, they fell in love.

Lee was understandably distraught and decided to move out from their home in Springs, boarding a cruise ship to Europe. Ruth moved in the very same day.

During the early months of their love affair, Klingman was frustrated by Pollock’s lack of interest in art. Then, one day in July, she insisted he painted a new piece for her. Pollock relented and set to work. The result, according to Ruth, was the piece ‘Red, Black and Silver’, although the attribution is disputed by most art critics.

Had Jackson Pollock found new inspiration, a new muse in Ruth? Would he have crawled out of his trance, ready to revolutionize the art world yet again?

We will never know.

On August 11, 1956, at 10:15 pm, Jackson, Ruth and a third friend, Edith Metzger, were driving in Pollock’s Oldsmobile convertible.

Jackson was at the wheel, driving under the influence of alcohol.

Less than a mile away from his Springs home, the Oldsmobile veered off road and crashed. Ruth was the only survivor.

The relationship between Lee and Jackson at the end may have been stormy, for sure, but after Pollock’s death, Krasner kept his memory and legacy alive. She ensured that his short-lived fame did not peter out, snuffed by the new American trends, such as Pop art and hyper-realism — definitely more figurative in style.

Pollock’s art was divided in its genesis. It came from a struggle between conscious and unconscious; it derived from controllable and uncontrollable elements; it was driven by anti-conformism but backed by the establishment.

And so his legacy was, and still is, divisive. You may love him, or you may despise him. But surely you cannot ignore him.

LINKS/SOURCES

Biographies

https://www.jackson-pollock.org/

https://www.scribd.com/book/293577907

https://www.scribd.com/book/282453888

Thomas Hart Benton

http://www.artnet.com/artists/thomas-hart-benton/

Jungian Psychology

Life Magazine article

http://www.theslideprojector.com/pdffiles/art1/pollockarticle.pdf

Fractal theory

http://www.jstor.org/stable/25160299

Representing the Unconscious

https://www.academia.edu/24085361/Jackson_Pollock_Representing_the_Unconscious

Pollock and Jazz

https://www.academia.edu/10164140/Jackson_Pollock_and_Jazz_Inspiration_or_Imitation

Pollock, Abstract Expressionism and the CIA

https://daily.jstor.org/was-modern-art-really-a-cia-psy-op/

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20161004-was-modern-art-a-weapon-of-the-cia

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/modern-art-was-cia-weapon-1578808.html

https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/24909963.pdf

Ruth Klingman

https://www.vanityfair.com/culture/2012/09/jackson-pollock-ruth-kligman-love-triangle