Known as ‘the father of modern fantasy’ his epic tales of legend and lore have been enjoyed by millions of people all over the world — devoured in popular books and adapted for Hollywood blockbuster films. Unbelievably bright, he was a distinguished university professor, poet, historian, and expert linguist. As a child, he even made up his own languages for pure fun. He gave us complex and fanciful creatures including hobbits, orcs, and elves set in an prehistoric Middle-earth. Some theorize his made up worlds are symbolic of his country’s past power struggles, influenced by his devout Roman Catholic faith, or simply the genesis of his personal experiences. In any case, there is no denying his glorious imagination and his rightful place among the greatest writers of all time.

But who was the creator of The Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings? Today on Biographics we explore the life of J.R.R. Tolkien.

Formative Years

Before bank clerk Arthur Tolkien and Mabel Suffield welcomed their son into the world, the English couple moved to South Africa. Here, Arthur had high hopes of advancing his career and providing a comfortable life for their budding family. John Ronald Reuel (known as “Ronald” to most) was born in Bloemfontein, South Africa on January 3, 1892. Not long after, another son Hilary was born, completing the Tolkien family.

Tolkien’s childhood in Africa was cut short when his mother decided the boys would be better educated in their native England. At the age of three, Tolkien and his mother and younger brother left for their homeland while Arthur stayed behind to settle the business. He was planning to join them but never made it — falling ill and dying of a severe brain hemorrhage (a complication of rheumatic fever) on February 15, 1896. At the time, the spread of disease and contagions were feared and travel took many weeks, if not months. Arthur’s body was laid to rest without family by his side.

Having spent just a small fraction of his early years in Africa, Tolkien had few memories from the time. However, one tale persists yet the facts remain uncertain. According to the story, the then-toddler Tolkien stumbled upon and was bit by a baboon spider (a kind of tarantula) in the garden. Tolkien ran screaming and his nurse immediately snatched him up and sucked the venom out from the wound. Tolkien later said, “…he could remember a hot day and running in fear through long, dead grass, but the memory of the tarantula itself faded, and he said that the incident left him with no especial dislike of spiders.” Still, fans and armchair psychologists alike speculate whether the tarantula influenced the presence of man-eating spiders in Tolkien’s later fictional works.

Back in England, Mabel and the boys settled with family in the West Midlands — first in Kings Heath and then in Sarehole. On one hand, and especially in the city of Birmingham, the West Midlands was urban, dark, and industrial. On the other hand, it was the idyllic English countryside with lush with green grass, trees, and a corn mill in the rural hamlet of Sarehole. Between the ages of four and eight, Tolkien lived across the street and within 300 yards of the Sarehole Mill and Moseley Bog. He spent many hours playing there with his younger brother — and being chased by the miller’s son, whom the boys nicknamed the “White Ogre.” The Shire, Tolkien’s imaginary land of Hobbits, was inspired by Sarehole. In The Hobbit, he writes of Bilbo Baggins “running as fast as his furry feet could carry him down the lane, past the great Mill, across The Water and then on for a mile or more.”

Tolkien’s mother homeschooled the boys at first, teaching the young Tolkien botany and the basics of Latin. Tolkien could read fluently by the age of four and write soon after. He loved drawing landscapes and trees but his favorite studies were those involving languages. Later, he would attend King Edward’s School in Birmingham which proved to be the perfect breeding ground for the boy’s natural curiosity and development of linguistics. Tolkien was an exceptional student who was capable of easily mastering ancient and modern languages including Greek, Latin, Spanish, Old English, Old Norse, Gothic and Finnish. The boy made up his own languages, including early variations of Elvish ones featured in his writings. At King Edwards, he made a number of close friends and formed a semi-secret society that enjoyed drinking tea and critiquing each other’s literary works. They called themselves T.C.B.S. (which stood for the Tea Club and Barrovian Society).

Myth and fairy-story must, as all art, reflect and contain in solution elements of moral and religious truth (or error), but not explicit, not in the known form of the primary ‘real’ world. J. R. R. Tolkien

Despite the earlier loss of his father, life for the young Tolkien was generally happy until two events altered the course of his life. In 1900, his mother decided to convert to the Catholic faith. This bold move left Mabel and her sons estranged from both sides of the family and in the fallout, Tolkien experienced isolation, loneliness, and poverty. Following his acceptance into the Catholic church, Tolkien remained devout in his faith for the rest of his life. And, he has been credited with being partly responsible for bringing another famous writer and friend, C.S. Lewis, back to Christianity. Tragedy struck Tolkien again in 1904 when his mother was diagnosed with diabetes — a sure death sentence for most before insulin was available. Sadly, Mabel died in the same year, on November 14. Tolkien was 12 at the time. Fortunately for Tolkien and his brother Hilary, their Catholic priest Father Francis Morgan stepped in and became their guardian and made sure the boys received everything they needed — both materially and spiritually.

Lúthien and Beren

Tolkien met his eventual bride Edith Bratt when he was 16, and she was 19. They were both orphans and lodgers at a boarding house run by a woman named Mrs. Faulkner. The two grew fond of each other and a friendship developed. And then, as it happens with teenagers, the pair became too close for Father Francis’ liking. He was horrified his ward was courting a Protestant woman and believed the relationship was a distraction from Tolkien’s school work. Father Francis forbade Tolkien to see or correspond with Edith until he was 21. This was a devastating blow to Tolkien but he obeyed the order. When his birthday approached, he wrote to his love and proposed marriage. Her reply was heartbreaking but offered a glimmer of hope, she was engaged to another man but his letter made her reconsider.

Edith agreed to meet Tolkien on January 8, 1913 at the train station in Cheltenham. They walked and talked for hours and Edith accepted Tolkien’s marriage proposal — breaking off her prior engagement. Edith converted to Catholicism and the couple married on March 22, 1916. Tolkien was 24 years old, and a few months shy of deploying to the Western Front. In a letter to his son Michael years later, “Tolkien expressed admiration for his wife’s willingness to marry a man with no job, little money, and no prospects except the likelihood of being killed in the Great War.”

Tolkien was a true romantic and Edith was his muse. He wrote of her, “…her hair was raven, her skin clear, her eyes brighter than you have seen them, and she could sing — and dance.” Tolkien was so mad for Edith he created the fictional pair of star-crossed lovers based on their romance: Lúthien, daughter of the Elven King of Doriath, and Beren, a mortal man. They fall for each other when Beren discovers Lúthien singing and dancing in a glade. Yet, their love can never be since Beren is destined to die. Alas, her disapproving father the King sends Beren on a task he knows the man cannot complete. The full story of Lúthien and Beren was left unfinished during Tolkien’s lifetime but served as an important backstory in The Hobbit. Tolkien’s son Christopher later published Lúthien and Beren as a chapter of the saga, The Silmarillion.

Edith and Tolkien enjoyed a long and happy marriage to each other and they had four children: John Francis, Michael Hilary, Christopher John, and Priscilla Mary Anne. Tolkien was a devoted father and loved his children, often making up fanciful stories for them. From 1920 to 1942 at Christmas time, Tolkien illustrated letters to his children…introducing new characters such as the North Polar Bear, Snow Man and others, each year. Three years after his death, these intimate stories were published as Letters from Father Christmas by the Tolkien estate.

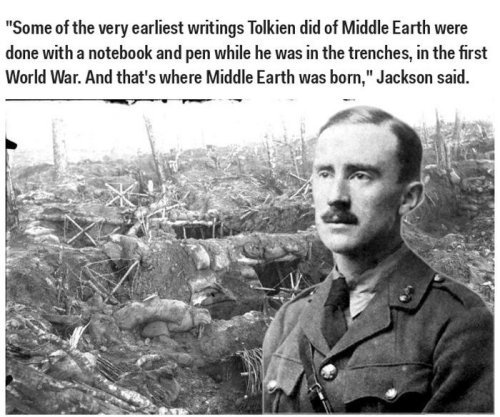

The Great War

Believing he was in his own words, “a young man with too much imagination and little physical courage,” Tolkien did not rush to join the British military when war broke out. Instead, he returned to Oxford where he had achieved a first-class degree in June of 1915. Tolkien was busy working on poems and his invented languages at the time. Eventually though, Tolkien enlisted as a second lieutenant in the Lancashire Fusiliers and was sent to active duty on the Western Front just in time for the Battle of the Somme (also known as the Somme Offensive). The Battle of the Somme remains one of the bloodiest military battles in history. It lasted four long months and on the first day alone, British troops suffered over 57,000 casualties. In total, over a million men lost their lives including 420,000 British soldiers.

Fighting in the Great War, Tolkien witnesses the horrors of trench fighting and lived in deplorable, unsanitary conditions. It was hell on earth for Tolkien and his comrades who stood by as their friends suffered and died alongside them. They spent their days and nights with little relief and endured infestations of lice that feasted on their flesh. As a result, Tolkien came down with “trench fever,” a major medical problem of World War I. So severe was the lice, a chaplain staying with Tolkien’s unit later recalled:

“… We dossed down for the night in the hopes of getting some sleep, but it was not to be. We no sooner lay down than hordes of lice got up. So we went round to the Medical Officer, who was also in the dugout with his equipment, and he gave us some ointment which he assured us would keep the little brutes away. We anointed ourselves all over with the stuff and again lay down in great hopes, but it was not to be, because instead of discouraging them it seemed to act like a kind of hors d’oeuvre and the little beggars went at their feast with renewed vigour.

Sick and unable to fight, Tolkien left the battlefront to recover in a Birmingham hospital in November of 1916. Through 1917 and 1918 Tolkien had recurring bouts of the illness and he spent the time in remission doing service at home and at various camps. Tolkien most likely escaped death on the battlefront precisely because he became ill. Sadly, all but one of his close friends, including those from the T.C.B.S., perished in the war. As a writer, this tragedy of loss and first-hand experience in battle provided Tolkien with a keen sense of awareness. From the unpublished, The Book of Lost Tales, Tolkien writes, “… in huts full of blasphemy and smut, or by candle light in bell-tents, even some down in dugouts under shell fire.” In The Hobbit, The Battle of the Five Armies is thought to draw upon Tolkien’s wartime experiences, as well as the Dead Marshes and Black Gate of Mordor in The Lord of the Rings.

On November 11, 1918, the Armistice was signed marking the end of World War I.

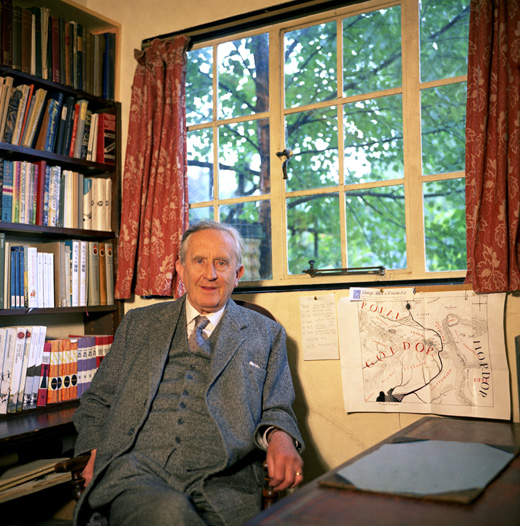

The Professor

Tolkien was appointed Assistant Lexicographer on the New English Dictionary (the “Oxford English Dictionary”) in 1918 but stayed on the job for only a short while. In the summer of 1920, he accepted a post as a Reader with the University of Leeds. At Leeds, he taught and collaborated with other authors, continued writing The Book of Lost Tales, constructed languages, and founded reading and social clubs like the “Viking Club,” where undergraduates had an affinity for Old Norse sagas and drinking beer.

In 1925, Tolkien finally received his professorship at Oxford, the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon. Tolkien was right at home in academia and fit in remarkably well with the predominantly male culture. He reveled in the lectures, research, and exchange of ideas with students and fellow professors. Tolkien did not publish many scholarly articles yet he was extremely influential. One lecture worth mentioning altered the modern study of the Old English epic tale Beowulf and was first delivered in 1936. In “Beowulf, the Monsters and the Critics,” Tolkien argued the monsters: Grendel, Grendel’s mother, and the Dragon, are not merely extraneous to the narrative but should be a focus of study. Tolkien believed critics put too much emphasis on the historical elements of the tale instead of looking at it as a work of art.

At Oxford, Tolkien befriended colleague C.S. Lewis, best known for his fantasy series, The Chronicles of Narnia. The two men bonded over their shared love of mythology and began meeting regularly for a glass, a joke, and to criticize each other’s poetry. The meetings were so enjoyable and useful, they invited others to join. The informal group, known as “The Inklings” eventually grew to 19 members and they met once a week, late at night, sometimes not wrapping up until two or three o’clock in the morning. As was the practice, Tolkien shared manuscripts of works-in-progress with The Inklings and received energetic feedback from the group. Among other writings, Tolkien brought original poetry, sections from The Hobbit, excerpts from “The Notion Club Papers,” and each new chapter of The Lord of the Rings. There is little evidence to support the suggestion by some that the men had a more spiritual purpose to their meetings, or an “inkling” of the Divine Nature. The Inklings continued to meet regularly for 19 years. Together with Tolkien and Lewis, some of the more distinguished members of The Inklings included Neville Coghill, Hugo Dyson, Owen Barfield, and Charles Williams.

In 1945 Tolkien changed his chair at Oxford to the Merton Professorship of English Language and Literature, which he held until his retirement in 1959.

The Storyteller

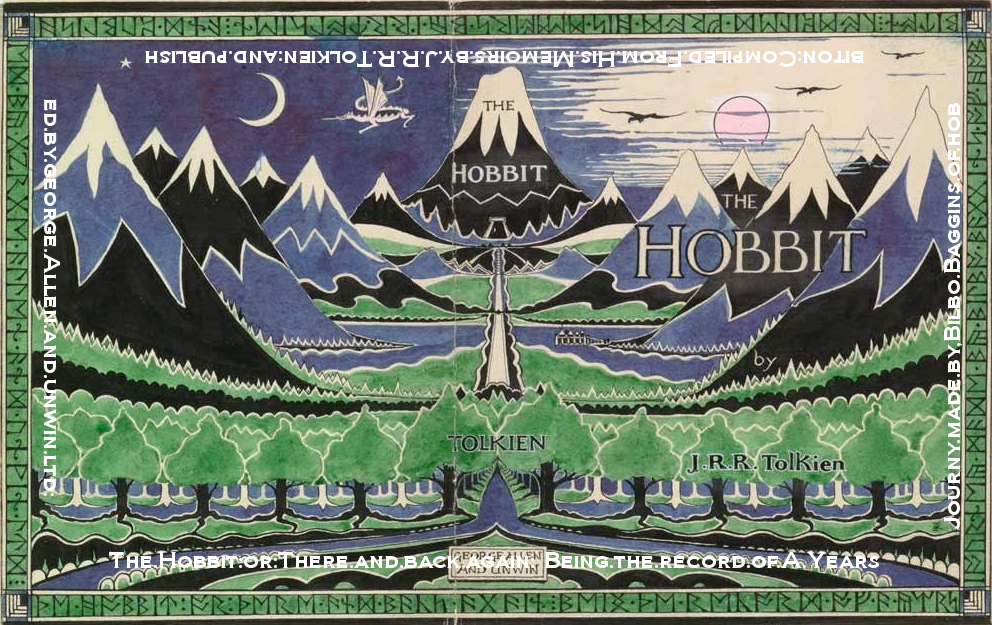

One hot summer day in 1928, Professor Tolkien was grading exam papers, which he described as “soul-destroying.” He came upon a blank page — and without thought —wrote down, “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.”

But, What was a hobbit? And, Why did it live in the ground? Tolkien needed to find the answers to these questions. He said later, “Names always generate a story in my mind. I thought I’d better find out what hobbits were like.” Then, in true Tolkien fashion, he dove headlong into the creative process and concocted a tale to tell his younger children, and share amongst The Inklings. In 1936, an incomplete copy of The Hobbit wound up in Susan Dagnall’s hands, an employee of the publishing firm of George Allen and Unwin. Recognizing the story’s potential, Dagnall convinced Tolkien to finish it and when complete, she presented it to her boss. He then tested it out on his 10-year old son who gave it a raving review. The Hobbit was published one year later in 1937, and was an immediate hit. In fact, it was so successful, the publisher asked Tolkien if he had any similar stories. Today, since the first publication, The Hobbit has sold over 100 million copies around the world and has been translated in over 50 languages.

What makes The Hobbit so enduring? For one thing, it lacks female characters and it is not, nor ever has been, politically correct. It is also a very long tale with poetry, and unlike other children’s fiction, does not have a central child figure for whom young readers can easily identify with. Although, the protagonist Bilbo Baggins is “only a little hobbit,” so he kind of acts like a surrogate child. Tolkien’s colorful descriptions of Middle-earth and its complex characters (goblins, elves, orcs, wizards, dragons, and hobbits of course) are richly portrayed. And for all the fantasy writers who came after Tolkien, hardly any can say their worlds were not, at least in part, influenced by The Hobbit. But, what set the story apart is the depth of emotion and moral courage Tolkien weaves into his heroic fiction. There are examples of this throughout The Hobbit including the death of dwarf leader Thorin Oakenshield, and Bilbo’s internal struggles to do what is right — betraying his friends while they try to reclaim the Lonely Mountain from Smaug the dragon. Bilbo feels an obsessive greed has overtaken Thorin and when Bilbo finds the Arkenstone, the greatest treasure of all, he decides to first hide it and then give it to his friends’ besiegers to be used as a bargaining chip. In the end Bilbo exposes himself and confesses because after all, they are friends.

After Tolkien’s publication of The Hobbit, he presented portions of The Silmarillion, including incomplete stories of Lúthien and Beren, to Stanley Unwin hoping for a warm reception but his reader felt the stories were not commercially publishable. They contained too much poetry. Tolkien was disappointed at the news but soon found himself busy writing the sequel to The Hobbit. Tolkien’s opus, what would become The Lord of the Rings, was first published in three parts: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King between 1954 and 1955. And, it took him over a decade to write it. Unwin’s son, who was by now an adult, was heavily involved in pushing a temperamental Tolkien along to finish it. Thinking it would be a relative unimpressive release, and a loss to the firm, the publishers grossly underestimated The Lord of the Rings public appeal. True, it had mixed reviews — from damning to glowing and everything in between. BBC adapted it into 12 condensed episodes, elevating its popularity further. Then, in the mid-1960s a pirated paperback version was released which caught the attention of American readers. A sort of cult developed based on the newfound popularity of fantasy literature and Tolkien was made a rich man. He was not entirely happy though, even if he was flattered. Partly, because rumors circulated of party-going cult readers ingesting LSD and reading The Lords of the Rings. And some overzealous fans, who Tolkien referred to as lunatics, were calling his home demanding to know if Frodo had succeeded in his quest.

The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings certainly receive all the glory but Tolkien authored a number of other articles and essays during his lifetime including: The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays; one Middle-earth related work, The Adventures of Tom Bombadil; editions and translations of Middle English works such as the Ancrene Wisse, Sir Gawain, Sir Orfeo and The Pearl, and stories the Imram, The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm’s Son, The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun, Farmer Giles of Ham, Leaf by Niggle, and Smith of Wootton Major. Following his death, The Letters from Father Christmas were released by the Tolkien estate, and later, son Christopher saw to it that his father’s Silmarillion and a number of other incomplete writings under the title of Unfinished Tales of Númenor and Middle-earth were published.

After his retirement from Oxford Tolkien moved to Bournemouth and on November 29, 1971 the love of his life, Edith died. Nearly two years later on September 2, 1973 Tolkien followed. As a final testament to their love, and at Tolkien’s instruction, they were buried in a single grave. On their tombstone, “Beren” is engraved under his name and “Luthien” appears under Edith’s.

Accomplishments & Legacy

Tolkien shal remain a celebrated literary figure through the ages as his life work continues to inspire the fantasy genre. Around the world, his characters and places have become the namesake of various street names, companies, mountains, plants, and objects. There are even asteroids named after Bilbo Baggins and Tolkien himself. In England, there are seven blue plaques that commemorate places associated with Tolkien.

Tolkien was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II in 1972. And, he holds a number of other achievements and awards including: an honorary degree from The National University of Ireland and University of Liege in 1954, and the Locus Award for Best Fantasy novel for The Silmarillion in 1978. In the 2000s, Tolkien ranked on BBC’s ‘greatest Britons’ list and The Lord of the Rings was the UK’s ‘best loved novel’ (2003) and ranked among ‘The 100 Greatest British Novels’ (2015). Tolkien was placed sixth on the list of ‘The 50 greatest British writers since 1945’ published by ‘The Times’ in 2008. In 2009, he was listed as the fifth top-earning ‘dead celebrity’ by Forbes.

From 2001 to 2003, New Line Cinema released The Lord of the Rings as a trilogy directed by Peter Jackson. The series was extremely successful and won numerous Oscars.

From 2012 to 2014, Warner Bros. and New Line Cinema released The Hobbit, a series of three films based on The Hobbit. The first in 2012, The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, the second in 2013, The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug, and the final installment in 2014, The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies.

Most recently, Amazon retained the rights to adapt The Lord of the Rings for its Prime streaming service. The multi-season adaptation, will focus on “previously unexplored stories based on J.R.R. Tolkien’s original writings,” according to a representative for the Tolkien Estate.

Tolkien’s Middle-earth is surely the gift that keeps on giving. And it is quite amazing, considering he wrote it all in his spare time.

J.R.R. Tolkien Video Biography