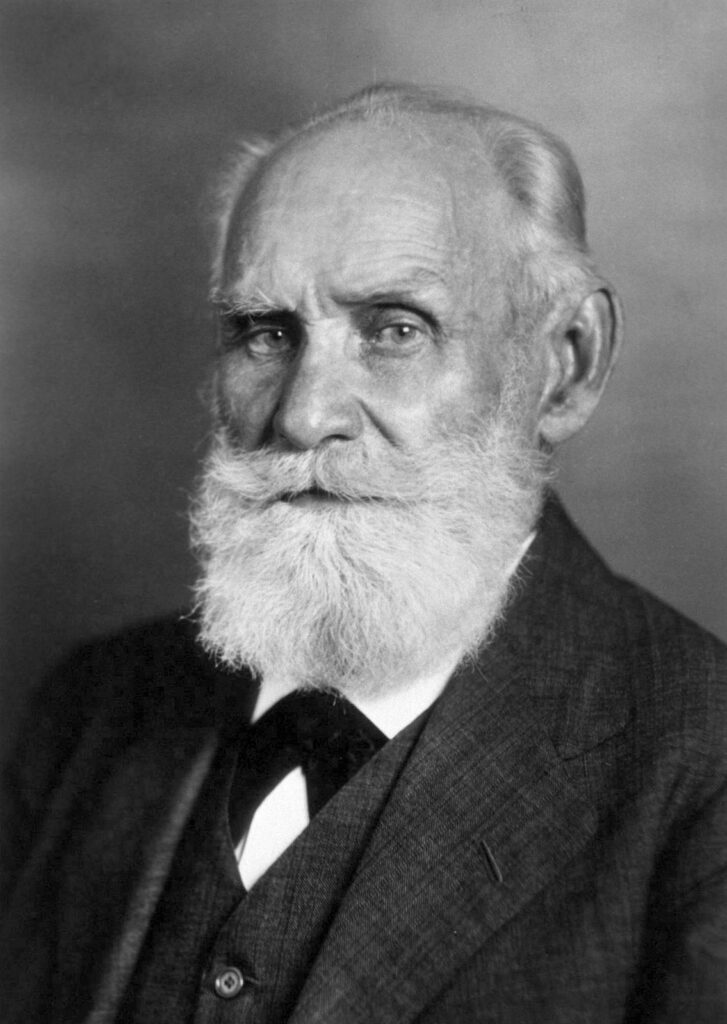

Everyone and their dog know about Russian scientist Ivan Pavlov and, well, his dog, and how he trained him to drool on command at the sounding of a bell. His discovery of conditioned reflexes won him a Nobel Prize in Psychology. Pretty straightforward, right? Wrong!

Much of what we know about Pavlov’s experiment has been misrepresented and mistranslated, so join me in today’s Biographics to learn the truth behind Ivan Pavlov’s research and his fascinating life. A word of warning: if you happen to watch these videos with your canine friends, this is one where you may want to cover their ears…

A Boy’s Favourite Uncle

Ivan Petrovich Pavlov was born in Ryazan, in the Russian Empire, about 200 miles from Moscow on the September 26, 1849. Ivan’s father, Petr, was the local Orthodox Parish priest, a well-liked and respected figure who supplemented the family’s income by growing his own vegetables and brewing his own vodka-based fruity liquor.

Ivan was a frail and sickly child, one you might immediately assign to the role of a bookworm. Except that he had absolutely no power of concentration, hated reading and had a pretty volatile temper. In fact, he avoided homework as often as he could, preferring to help Petr in tending to his plot of land.

At the age of eight, Ivan suffered a bad fall, plunging from a tall fence onto a stone slab. As he struggled to recover from his injuries, his godfather, also a priest, stepped in. For some reason, he believed that what the boy needed was not a proper trauma assessment or a doctor, but

“Discipline, discipline and more discipline”

So he took Ivan to his monastery, where for several months the boy lived like a monk. The therapy did produce some results; bored out of his mind, Ivan started doing something he had never considered: reading! With little other recourse, the young boy learned to enjoy it, devouring the monastery’s library.

When he returned home, his personality had changed. He was calmer, more focused, and had a great desire to learn. Petr reignite his hopes of sending Ivan to seminary to become a new addition to the Pavlov Family’s roster of clergymen.

The other pivotal moment in young Ivan’s life was when his uncle — also a priest, also named Ivan — moved in with the family.

If Petr wanted to provide his son with strong role models, he had done a rubbish job, as Uncle Ivan was a terrible priest. Shortly after he was assigned his most recent church, local parishioners had started reporting ghastly sightings of a white, robed figure stalking the graveyard. Bodies were dug out from their tombs and simply disappeared. The church bells had the habit of going off at the most ungodly hours of the night. Of course, it was all thanks to Uncle Ivan, who enjoyed playing a prank or two while drunk like a baboon at a bachelor party.

When the parishioners found out, they cornered Uncle Ivan, thrashed him like a snare drum at a Napalm Death recording session and kicked him out of the village.

Uncle Ivan’s only choice was to move in with his brother Petr, where apparently he sobered up and developed a strong bond with little Ivan. The boy loved the elder Ivan, from whom he heard stories about his other uncle — also a priest, also named Ivan. Because why choose new names when you can confuse amateur historians instead?!

Now, about Uncle Ivan II. Was he a good priest? Not really. His favourite past-time was a sort of brawling much in fashion during those days. Basically, the men of one street, or an entire village, would fill up on enough vodka to floor a company of Varangians, then challenged a rival team of equally intoxicated sluggers. Think of it as a Russian donnybrook.

Now, I don’t know about you, but my local priest only drank weak tea and a glass of port on Christmas Day, and he only challenged the village postman at chequers.

Anyhow, Uncle Ivan II once took his brawl too far, and he died as a result of his injuries.

I am not sure if such role models would encourage a young mind to take up priesthood, but these experiences surely taught a vital lesson to young Ivan: the importance of moderation and the avoidance of all excesses in life.

With a strong moral compass installed by the tales of his elder Ivans, Pavlov was finally sent to study at a seminary. His experience at the religious school started promisingly, but soon Ivan was distracted by the irresistible allure of a demanding mistress: science.

During the early 1860s, Russian society had initiated a period of economic, social, and cultural reforms promoted by Tsar Alexander II, who ascended to the throne in 1855. Most notable was the abolition of serfdom, which totally revolutionized the Russian economy. Another key element of these reforms was the promotion of science to foster modernization of the State. As a result, local public libraries were stocked with scientific works by both Russian and foreign author previously unavailable.

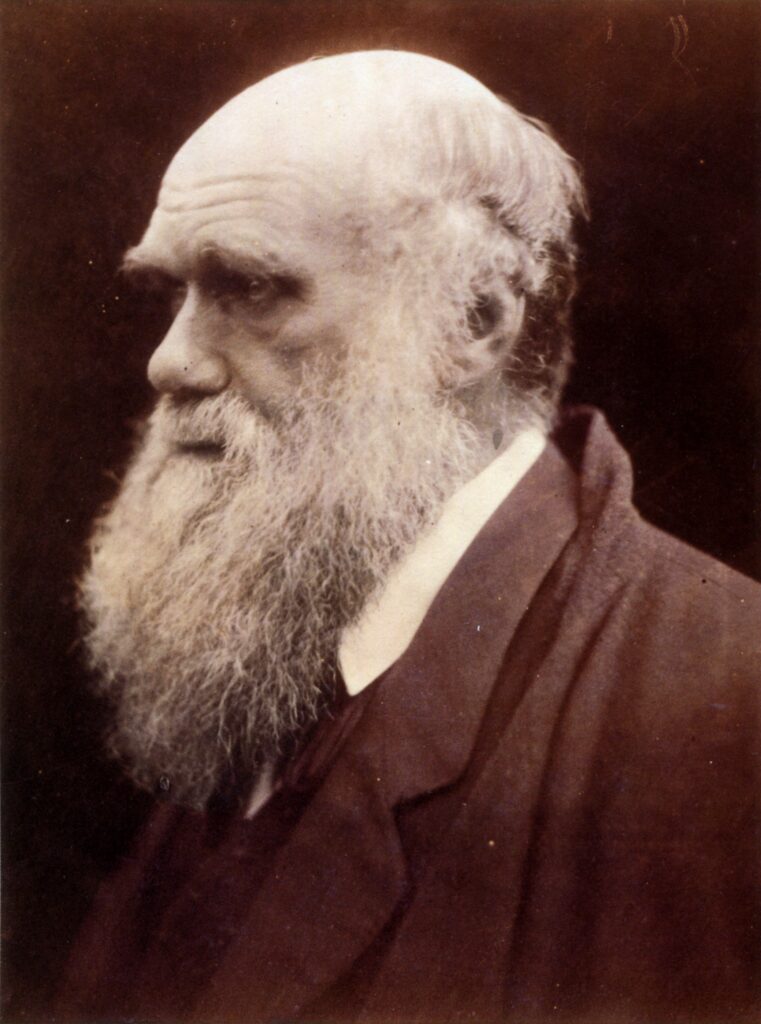

Ryazan’s public library was flooded by Ivan and his friends, who had formed a discussion circle to review and analyze modern scientific discussions. Works like Charles Darwin’s The Origin of the Species or the journals by radical scientist Dmitry Pisarev. One book would be particularly relevant in Ivan’s future career: Reflexes of the Brain by Ivan Sechenov, in which the author argued that all human behaviours and thoughts could be explained as a result of machine-like reflexes and reactions.

Young Ivan’s thirst for knowledge was so avid that he would not allow any obstacle to come in his way. If the seminary demanded that he studied all day, he would read at night or very early in the morning. When access to the library became so crowded that fistfights exploded regularly, he convinced a librarian to keep a window always open at the back – so that he could climb into a reading room undisturbed and get on with his extra-curricular studies.

One of the Karamazovs?

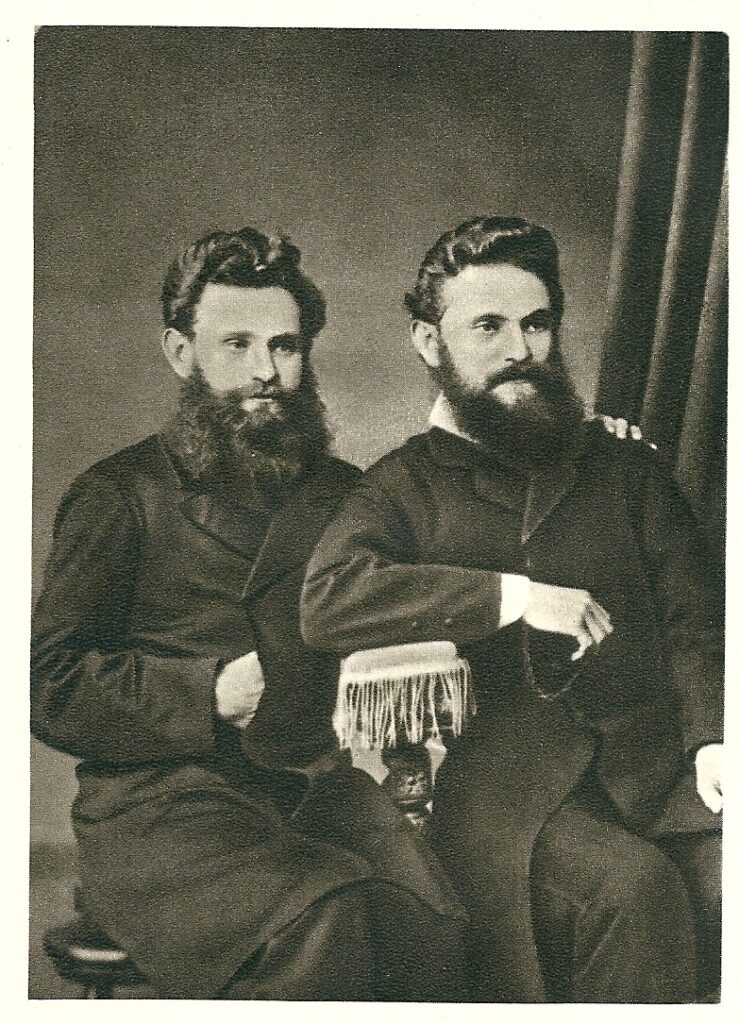

In 1869, Ivan could no longer continue his ruse of progressing his religious and scientific studies along parallel tracks. He had to let go of something, and that something was religion. He quit the seminary and enrolled at the University of St. Petersburg to study chemistry and physiology – the branch of biology that deals with the normal functions of living organisms and their parts.

Petr Pavlov was not pleased with this decision, but Ivan had put his foot down. He would stand by his rational choices, regardless if these would sour his personal relationships. In a later letter to his future wife, Ivan compared himself to one of the Brothers Karamazov, from the novel by Fedor Dostoyevsky: one of the brothers, also named Ivan, was a rationalist and an extreme skeptic, condemned to social isolation for his nihilism.

By 1875, Ivan had earned a degree and a doctorate from the Imperial Medical Academy and continued his studies under renowned physiologists Rudolf Heidenhain and Carl Ludwig. At the same time, he had enrolled at the Academy of Medical Surgery, wherein 1879 he attained his third degree and was awarded a gold medal for academic results.

Ivan’s studies were crowned by his doctor’s thesis, published in 1883. Its title was

“The Centrifugal Nerves of the Heart”

Which sounds like a bad Bonnie Tyler outtake, but was actually a pioneering work in which he laid down the basic principles of the trophic function of the nervous system. In other words: the role of the nervous system in nutrition.

In the meanwhile, Ivan had married a teacher called Seraphima Karchevskaya, also known as Sara, in 1881. Their first years together were not happy. Initially, the couple lived in almost complete poverty, while Ivan was still perfecting his studies. They had to frequently crash at friends’s houses or rent bug-infested attics. Tragically, Sara’s first pregnancy ended in a miscarriage; according to the doctors of the time, this was caused by Sara’s constant attempts to keep up with Ivan, a very fast walker. It seems more likely that the couple’s unhealthy living conditions played a role.

Ivan and Sara soon tried to have another child, and Wirchik was born shortly afterward. Unfortunately, the baby boy died suddenly while still an infant.

Despite their grief, the couple’s life improved in the following years. In 1890, Ivan received a series of appointments that improved their financial situation. He was first invited to direct the Department of Physiology at the Institute of Experimental Medicine, a post he would hold for the next 45 years; then, he was hired by the Military Medical Academy, first as Professor of Pharmacology, then as Chair of Physiology.

All that hard work and study had eventually paid off. Ivan and Sara were also blessed with four healthy children, Vladimir, Victor, Vsevolod and Vera.

With his professional and personal life on track, Ivan Pavlov launched into the research that really mattered to him, the one on the physiology of digestion. This took place at the Institute of Experimental Medicine, from 1891 to 1900, and would make him a household name.

E.g. “But before we look at Pavlov’s brilliant hands on approach to science, how about you take a hands-on approach to knowledge with Brilliant?” – assuming that’s the sponsor.

Or

“Unlike Ivan, you don’t need nine years to find out about how the digestive system works, in fact 15 minutes would be enough. Try Blinkist etc etc” if that’s the sponsor.

Or:

“Before we get into Ivan’s experiments on dogs, let me tell you what I feel like doing to people who harm dogs. That’s right: shoot them with a tank! And you know where you can practice with a tank? That’s right, War Thunder!”.

If that’s the unlikely sponsor]

A man’s best friend,

a dog’s worst enemy

OK, back to Ivan Pavlov and his experiments. First, let’s cover his methodology.

It may sound commonplace today that science should be grounded on data produced via experimentation, but when Pavlov emerged as a notable scientist, this wasn’t necessarily a given when it came to physiology.

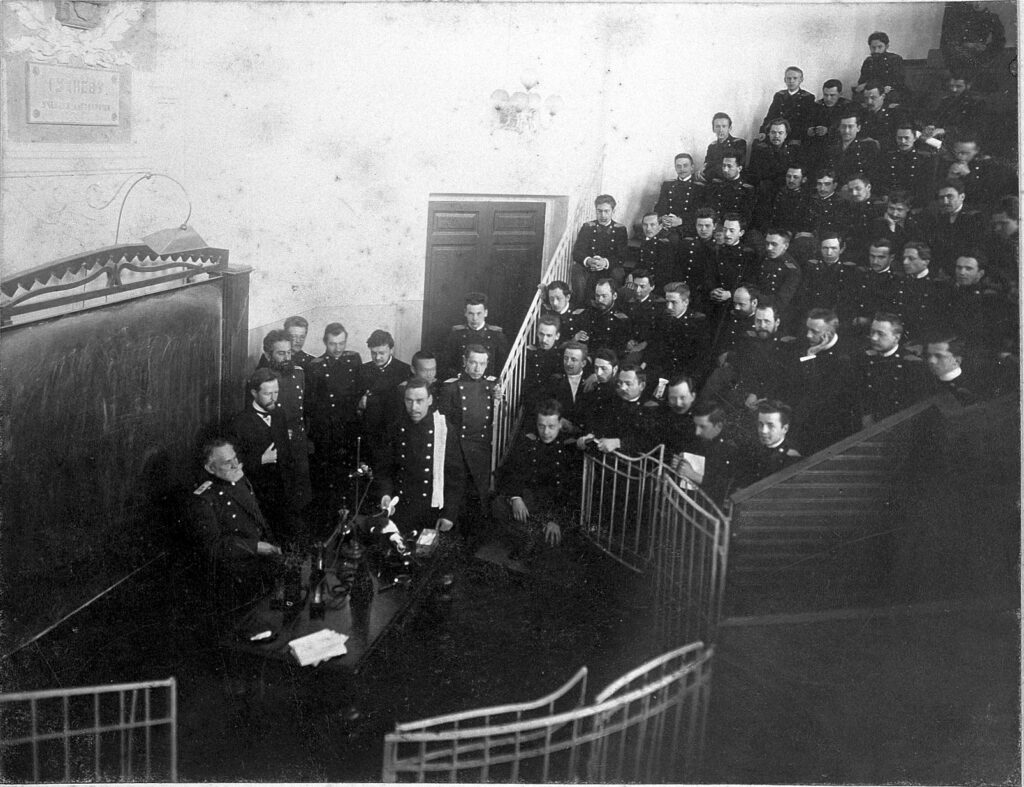

Pavlov was the first physiologist in the Russian Empire to devote himself to repeated experimentation, applying a factory-like approach to his lab.

Pavlov recognized that meaningful changes in the normal functions of a living organism could be assessed only over time. Pavlov’s contemporaries would experiment on an animal, then discard it, or even kill it once the experiment was done.

Pavlov instead preferred to keep his animals alive — especially dogs — in order to document physiological changes over a longer time span. He referred to this method as “chronic experiments”.

And this is the moment when you may want to cover your dog’s ears or send them playing somewhere else.

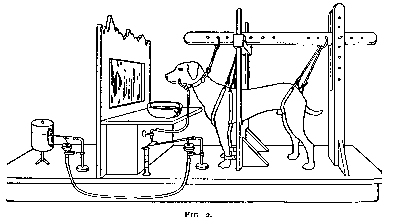

If Pavlov’s lab was a factory, then the dogs were his machines. He performed surgical operations on every test subject, opening a ‘fistula’ along their digestive traits. A fistula is an opening in a living organism that allows one to observe the inner workings of its organs. Pavlov needed these fistulas opened for two reasons: 1) to observe the functioning of his dogs’ digestive functions, in particular, the production of gastric juices; and 2) to collect said secretions.

So, yeah, Ivan Pavlov may have not systematically killed his lab animals, but their treatment wasn’t a walk in the park – which I suppose is what they were probably hoping for, considering they were dogs.

It was a treatment that was painful, at best, and caused the death of the subjects at worst. Particularly in his early experiments, Pavlov was constantly stymied by the difficulty of keeping his subjects alive after operating on them.

Even if one of his ‘machines’ tragically died, Ivan was always ready to replace them. But what exactly did this factory, or lab, produced? Pavlov and his team cranked out scientific papers on the physiology of the digestive system, new research techniques, and an important by-product: gastric juice – liters of it.

Ivan Pavlov was always strapped for research cash and he had stumbled upon a lucrative side gig: Russian patients suffering from dyspepsia were ready to pay good money for canine gastric juice, considered an effective treatment at that time. Dyspepsia is more commonly referred to as ‘indigestion’ and includes symptoms such as bloating, discomfort, nausea. So yeah, if you are feeling nauseous and bloated, what better remedy than gulping down a nice glass of warm, thick, moist, pungent gastric juice freshly harvested from a fistulated drooling dog?!?

Can you give me a minute, I think I am going to be si-

[Editing note: screen cuts abruptly to black, with a short burst of static noise. The camera then returns to Simon, who continues as if nothing had happened]

Pavlov had the perfect setup for his indigestion medicine factory: five large young dogs, selected for their voracious appetites, were harnessed on a long table. Each dog was subjected to an incision of the esophagus: this opened a fistula, from which a tube led to the collection vessel. Each of these dogs faced a stand, tilted to display a large bowl of minced meat, just out of reach. This stimulated the production of saliva and gastric juices.

By 1904, Pavlov’s side gig was selling more than three thousand flagons of dog gastric juice per year, raking in profits that would increase his lab budget by 70 percent.

The Experiment

Besides capitalizing on his own brand of furry Taylorism, Pavlov began his research of what he called “psychic secretions” – which sounds like something Dr Stantz or Dr Spengler may want to analyze, too. But in simple terms, psychic secretions were drool produced by anything other than direct exposure to food.

And here we get to Pavlov’s famous experiments. Just to clarify – it wasn’t a single occurrence in which he rang a bell to get a dog to salivate, as sometimes thought by modern popular culture, but a ‘chronic experiment’ in line with his scientific doctrine.

This is how it worked.

Pavlov’s main research was meant to study the salivation of dogs in response to being fed. However, he soon noticed that the dogs would begin salivating when they heard the footsteps of the assistant bringing their food.

Pavlov’s hypothesis was that any object or event which the dogs learned to associate with food would trigger the same response as the food itself.

He started from the idea that dogs – or other complex organisms – were hard-wired to respond instinctively to certain stimuli. In other words: an ‘unconditioned stimulus’, for example: food, will elicit an ‘unconditioned response,’ or salivation. Dogs will salivate in the presence of food. It’s not a behavior they need to learn.

[Unconditioned Stimulus] -> [Unconditioned response]

Pavlov then devised a series of experiments to validate his initial hypothesis. The first step was to introduce a neutral stimulus: this could be a metronome or an electric buzzer – which in a mistranslated paper became the famous bell.

The neutral stimulus did not elicit any response.

[Neutral Stimulus] -> [No conditioned response]

Next, it was time to begin the conditioning procedure, that is associating the neutral stimulus with the unconditioned stimulus. In this example: introducing a clicking metronome before the dog chow was served.

Finally, Pavlov played the metronome but failed to produce the food. I am sure the dogs were dead disappointed, but what mattered to the scientist is that the clicking in itself … did increase the drooling!

So now a conditioned stimulus had elicited a conditioned response, also described as a ‘conditional’ response in some translations from the original Russian articles.

[Conditioned Stimulus] -> [Conditioned response]

Pavlov’s experiments would become more sophisticated: for example, he tried playing around with specific metronome speeds, like serving food only when it clicked at sixty beats per minute. Over time, his dogs became so specifically conditioned that they failed to salivate at any other setting.

Pavlov began to deduce that there were colliding forces of “excitation” and “inhibition” at play. At first, a stimulus may spread broadly across the cerebral cortex, or the area of the brain responsible for processing inputs and maintaining cognitive functions. Later, in a potential second phase of selective reinforcement, the stimulus could be concentrated on one specific spot of the cortex.

I should reinforce here that Pavlov’s interest was always grounded in physiology and in the understanding of the digestive system. However, his work did have a huge impact on the field of psychology: Pavlov’s discoveries pushed behavioural psychologists into developing the concept of ‘classical conditioning’ also known as ‘Pavlovian conditioning’. This is a process of learning by association, which, according to behaviourists, can explain all aspects of human psychology.

In the 1920s, psychologist John Watson went as far as denying completely the existence of the mind, or consciousness, believing that individual behaviours, speech patterns, and emotional responses are simply a consequence of external stimuli which elicit certain responses via classical conditioning.

Such an approach, taken to the extreme, negates subjective experience. In other words, ten different people, exposed to the same input, would produce the same output. Interestingly, Pavlov never approved of the theories that behaviourists had built on the back of his experiments. The Russian scientist firmly believed in the importance of individuals in determining their behaviour. And while he, as a physiologist, did not have the answers, he hoped science would one day explain

“the mechanism and vital meaning of that which most occupied Man—our consciousness and its torments.”

Drooling over food, Spitting over the USSR

In 1903, at the 14th International Medical Congress in Madrid, Pavlov read a paper on «The Experimental Psychology and Psychopathology of Animals». His research was far from completed or exhaustive, yet his findings took the scientific community by storm.

Credit: Welcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

images@wellcome.ac.uk

http://wellcomeimages.org

I.P. Pavlov and seventeen of his associates standing outside the Physiology Department, Imperial Institute of Experimental Medicine, St Petersburg.

Photograph

1904 Published: –

Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

He only had to wait one year before he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1904

“in recognition of his work on the physiology of digestion, through which knowledge on vital aspects of the subject has been transformed and enlarged.”

From then on, the laurels piled upon Ivan’s head. In 1907, he was elected Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences; in 1912, he was given an honorary doctorate at Cambridge University; in 1915, he was made a member of the French Order of the Legion of Honour, following a lobbying campaign by the Medical Academy of Paris.

Which takes us just two years before a certain event that shook the World …

When the October Revolution of 1917 ousted Kerensky’s Government and Lenin rose to power, Pavlov was sixty-eight and had been a Nobel Laureate for 13 years. He had had no particular sympathies for the Tsarist regime, which had been notoriously stingy when it came to funding research. He wasn’t terribly fond of communism, either, and would not hide his feelings about it.

Ivan Pavlov was always vocal in his opposition to communism and its Russian incarnations. He only had two words to spare for Karl Marx:

“That fool”

And he wasn’t any kinder to the leaders of the Bolshevik Revolution. And yet his international standing was unassailable, and Ivan could get away with the most outspoken and ferocious critiques of the regime.

Pavlov considered Communism a “doomed” experiment that had turned Russia back into a nation of serfs, and he saw Bolshevism as a system of government that devalued culture and the intellectual strength of a nation.

How did Lenin treat this rogue, but celebrated scientist? At first, Pavlov and his family were treated like any other Soviet citizens, which means many of their assets were confiscated as property of the State, including the Nobel Prize money … money that could have come in handy for the tough times that lay ahead. From 1917 to 1920, the revolutionary government had to defend itself against the White Armies in the Russian Civil War, a situation that caused generalized famine and fuel shortages for Russian citizens.

Like most residents of Petrograd, the Pavlovs struggled to feed themselves and keep from freezing, as at least a third of Pavlov’s colleagues at the Academy of Sciences starved or froze to death. Pavlov barely struggled to keep his family alive by growing potatoes and other vegetables right outside his lab, and by collecting small amounts of firewood from a colleague.

In 1920, Pavlov wrote to Lenin’s secretary, seeking permission to emigrate to Western Europe or America, in search of better living conditions and more funding for his lab. Lenin immediately realized the negative PR repercussions of losing the country’s most celebrated scientist. He ordered Petrograd Party leaders to increase rations for Pavlov and his family and to make sure his working conditions improved.

Ivan Pavlov had prevailed over Lenin thanks to his prestige. Would he have the same luck with his successor? Josef Stalin started his climb to absolute power after Lenin’s death in 1924, and by 1927 he had launched one of his many purges, focused on intellectuals and scientists.

Pavlov was outraged, especially when restrictive measures were aimed at Jewish scientists. Now, in his private life, Pavlov was as anti-Semitic as Stalin. In his view, Trotsky was a

“vile yid”

And in 1928, Pavlov had complained to an American colleague that

“Jews occupy high positions everywhere … it’s a shame that the Russians cannot be rulers of their own land.”

But it is undisputed that the scientist had a strong sense of justice. At a time when vocal dissent may land you in a Gulag, or shot in the back of the head by a secret police goon, Pavlov wrote to Stalin complaining against the purge, saying that he was

“ashamed to be called a Russian.”

We don’t know Stalin’s reaction to such complaints, but we can speculate that he was not amused. Luckily for Pavlov, he could rely on powerful allies: Nikolai Bukharin, chairman of the Comintern’s executive committee, considered Pavlov indispensable and defended his case with Politburo members:

“I know that he does not sing the ‘Internationale,’ but despite all his grumbling, ideologically (in his works, not in his speeches) he is working for us.”

In a case of pragmatism triumphing over paranoia, Stalin agreed with Bucharin and ensured the Party would continue supporting Pavlov.

The scientist and his labs continued to prosper, even in the years leading up to Stalin’s Great Purge. Pavlov expanded his operations to three laboratories, staffed with hundreds of scientists and lab assistants, and was even permitted to collaborate with scholars in Europe and America.

But his relationship with the government was never easy. Apparently Moscow officials did not understand why their Big Boss allowed Pavlov to

“Spit on the Soviets”

… as politburo member Valerian Kuibyshev put it.

Kuibyshev, who was Chairman of the State Planning Committee, and had influence over government investment in agriculture, industry and science, tried to oppose Pavlov as much as he could, at least within the limits of what Stalin allowed him to do. This meant that Kuibyshev was forced anyways to fund Pavlov’s laboratories, but had no intention of ever honoring him. When a proposal was floated to celebrate Pavlov’s 80th anniversary as an affair of State, Kuibyshev put his foot down: no cake for him!!! At least not sponsored by the State. After all, couldn’t they just play him a metronome or something? That should do, right?

Legacy

For a while, Kuibyshev successfully prevented excessive displays of admiration toward the Nobel Laureate, but by 1934, the hostile official had been removed from his post. Because that’s how Stalin rolled.

A good occasion to publicly celebrate the pride of Russian science arrived on the 27th of February, 1936, although I am sure Pavlov would have preferred to avoid it. Why? Well, this occasion was his death. Ivan Pavlov worked in his laboratory until the very end, even after contracting a double pneumonia which eventually claimed his life.

The Soviet Government honored the great scientist by organizing a grand funeral, at which a hundred thousand mourners, including Party officials, filed past his casket.

Ivan Petrovich Pavlov was a physiologist until his very last day on Earth, and yet the impact of his work was most felt in Psychology.

His methods may have not been the most ethical, particularly when it came to our modern standards surrounding matters like animal cruelty.

More broadly, the classical conditioning theories he spawned, as well as behaviorist psychology in general, were criticized by later generations of psychologists for being too reductive. Even Pavlov did not fully agree with strict classical conditioning theory, as it did not allow for the individual conscience to play a role in human behavior.

Pavlov’s true enduring legacy lies in the use of a rigorous scientific method to prove the existence of conditioned and non-conditioned reflexes, which provided a foundation for the study of acquired human behavior and the use of positive reinforcement in learning.

SOURCES:

The Science of Ivan Pavlov

https://www.simplypsychology.org/classical-conditioning.html/

https://www.simplypsychology.org/pavlov.html

https://curiosity.com/topics/the-one-thing-you-know-about-pavlov-and-his-dogs-is-wrong-curiosity/

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/11/24/drool

https://www.nobelprize.org/search/?s=Pavlov

The Life of Ivan Pavlov

https://books.google.com/books/about/Ivan_Pavlov.html?id=MHA8ZYnEc5wC

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1904/pavlov/biographical/

https://www.thoughtco.com/ivan-pavlov-biography-4171875

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ivan-Pavlov/Opposition-to-communism