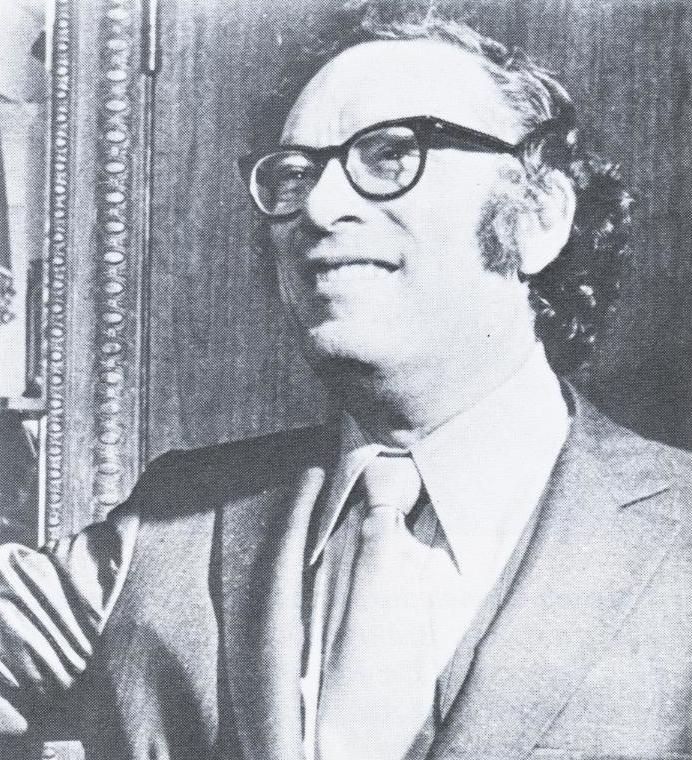

Today’s protagonist is universally recognized as one of the greatest science fiction writers in the history of literature. He won the Hugo and Nebula Awards, among many others, and is best remembered as the inventor of Robotics — the brilliant mind that conceived the Foundation series and the concept of Psychohistory.

During his long writing career, Isaac Asimov hopped back and forth between science fiction and mystery novels, essays, non-fiction textbooks, literary commentaries and dissertations on humor. He authored or edited nearly 500 books in his lifetime, including an average of 10 or more publications every year during his most prolific production period.

He wrote on Sherlock Holmes, Shakespeare, the Bible, the Romans, the Greeks, the Universe. He almost wrote a musical with a Beatle!

If I ever had a lazy day in my life, I’d just read all the titles of his many books. But as entertaining as a table of contents video would be, I will resist the temptation to recite dozens of book names, and do my best to instead give you a quick introduction to Dr. Asimov’s life, the main concepts behind his main work, and the secrets that underpin his writing techniques.

Candy and Magazines

A baby boy called Izaak Ozymov was born to Anna Rachel Berman and Judah Ozymov, a Jewish family of millers, in the small village of Petrovichi, in modern-day Russia, sometime between October 4, 1919 and January 2, 1920. Could I be more precise? No, actually. I can’t. Even Asimov himself did not know his exact date of birth, though he did select the 2nd of January as his birthday. So let’s just go with that.

At the age of one, Little Izaak had to face a lethal threat: he and 16 other children in his hometown developed severe pneumonia. Only he survived. Two years later, the toddler had to go through another life-changing event: longing for a better life, Anna and Judah took him and his younger sister by the hand and immigrated to the US.

Once the family relocated to Brooklyn, New York, they adopted a more Americanized spin on their name: ‘Asimov’. The boy Isaac demonstrated signs of a vivacious intellect from very early on. By the age of five, he was already fluent in Yiddish – his parent’s language – and English. He’d had also taught himself how to read, using the signs in the streets of Brooklyn as first reading material. And when he was seven, he took responsibility for teaching his younger sister how to read.

Street signs don’t make for a very entertaining read, but luckily, Isaac would soon graduate to much better material. Judah and Anna were the proud owners of a small general store: among other things, they sold candy and pulp fiction magazines. I can’t think of a better environment to grow a child!

Judah had a strong work ethic, expecting everybody in the family to help in the store. Isaac was no exception; He woke up every morning before 6 am, worked at the shop, went to school, went back to the store, and spent hours there doing his homework, as well as helping his parents with their business.

The upside was that he could have access to an endless supply of comic books and magazines, with the ones dedicated to science fiction being his favorites. Spending time in the closed confines of Judah’s shop, snacking on candy, and devouring sci-fi mags was Isaac’s idea of bliss. At this stage, he did not yet dream of becoming a writer; his ambition was simply to operate a small, closed kiosk in the New York Subway so that he could spend his days reading with the background hum of the trains. I guess this would make him a claustro-phile rather than a claustrophobe!

Around the age of eleven, Isaac began to write his own stories, but he still kept them hidden from the world. In the meantime, despite his harsh routine, which left little time to rest and study, Isaac thrived at school, excelling especially in scientific subjects. His progress was such that he was able to skip three grades. He graduated from high school when he was just 15!

This accelerated path continued in higher education. In 1939 – he was barely 19 at the time – Isaac graduated from Columbia University with a Bachelor of Science degree in chemistry. This subject had not been his first pick — freshman Asimov had originally set his sights on zoology. And he may have done very well in that field, too… however, when he discovered that he had to dissect an alley cat for an assignment, he switched to a specialty in which he was only required to handle molecules.

During his years at Columbia, Isaac had not neglected his writing. In June 1938, Isaac had finished writing a story entitled “Cosmic Corkscrew”, and his father encouraged him to submit it to John W. Campbell, a greatly influential sci-fi writer and editor of Astounding Science Fiction magazine.

Delivering the story in person via subway was two cents cheaper than mailing it, so Isaac did just that! To his surprise, Campbell invited him into his office to discuss his story. Two days later, Isaac received a rejection in the post, but it came with an encouraging note from Campbell.

Isaac remained in touch with the editor and, with his guidance, in March of 1939 he succeeded in having one of his stories professionally published for the first time, it was “Marooned off Vesta”

Nightfall

In March of 1941, John W. Campbell asked Asimov an intriguing question: what would happen if the inhabitants of a planet saw the stars only once every thousand years? Isaac used this idea as the basic plot for the short story “Nightfall”. He didn’t know it yet, but this was his first step to a legendary literary status.

In 1968, the Science Fiction Writers of America voted Nightfall as the best science fiction story of the pre-1965 era. No small feat for a 21-year-old.

What is so special about Nightfall? To summarize the general plot, the story is about a planet, Lagash, bathed in the perpetual sunshine of six stars. For the first time in more than a thousand years, an eclipse is predicted to darken the skies. How will the population react? Will they go insane? Burndown their whole civilization? The impending event creates raising tensions between the two groups of characters: Scientists and Cultists.

It is clear that Asimov sides with the former, who propose rational solutions, while the superstitious Cultists foretell of heavenly fire that will rain on Lagash.

This dichotomy of Science and Religion, first emerging in Nightfall, became a constant theme in Asimov’s writings. Later in life he stated:

“I have never, not for one moment, been tempted toward religion of any kind. The fact is that I feel no spiritual void. I have my philosophy of life, which does not include any aspect of the supernatural and which I find totally satisfying.”

Nonetheless, he never described himself as an atheist, considering it to be a negative and defeatist label. He preferred to be called a ‘humanist’, or even better a rationalist. Asimov always maintained an open-minded approach to religion and even published extensive guides to the Old and New Testament, analyzing them from a secular, historical perspective.

Father of Robotics

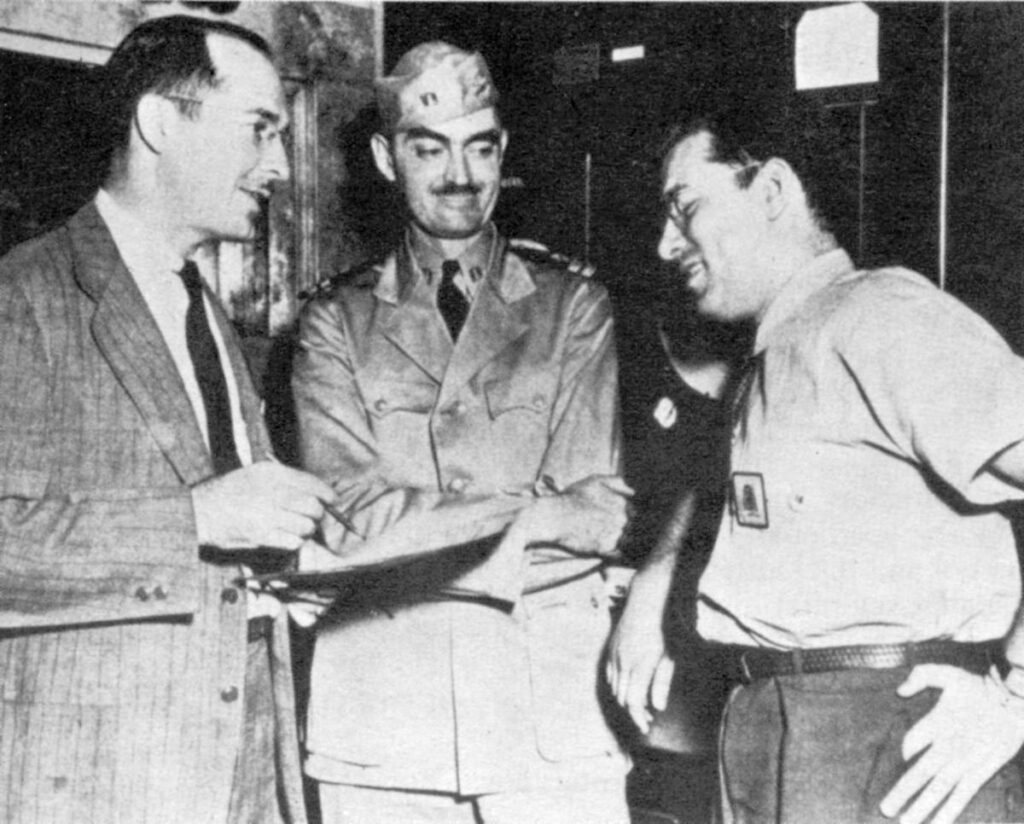

By 1942 Isaac Asimov had been drafted into the Armed Forces, serving as a chemist at the Naval Air Experimental Station in Philadelphia. The experience did not hinder his creativity, nor his compulsive writing.

That year, he completed and published another seminal short story, ‘Run Around’, which would revolutionize the use of robots as characters in literature.

The concept of artificial beings can be traced back to early 19th Century masterpieces such as Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’ or E.T.A. Hoffman’s ‘The Sandman’. Perhaps even earlier: even Homer’s Iliad mentions that the God Hephaestus was being served by maidens created out of gold.

The word ‘robot’ itself was first used by Czech playwright Karel Capek in his ‘Rossum’s Universal Robots’. Asimov, however, was the first to introduce the term ‘Robotics’. In ‘Run Around’ and subsequent works, sentient robots endowed with ‘positronic’ brains are regulated by the Three Laws of Robotics:

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws

A fourth (or more precisely a Zeroth law) was later added by Asimov:

- A robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm.

(Editorial/Production note, from Chase: The Three Laws of Robotics probably make for a good graphic. If we go that route, let’s leave enough room at the top of the card so that we can fade in the fourth/zeroth law, after the other three have been shown.)

Clearly, these imperatives are intended to protect humanity from the threat of a single robot rebelling or from a mass uprising. In his dozens of robot stories and novels, Asimov explores the consequences of following these rules to the extreme; for example, what would happen if robots were to prevent humans from doing anything at all, in an effort to protect them from potential harm?

The big theme, however, is the consciousness of the machines. As sentient beings, are they that different from humans? Was Asimov simply studying the implications of a human conscience trapped in a moral quandary?

Perhaps this is best explained by a recurring character of the ‘Robotics’ stories, robo-psychologist Dr Susan Calvin.

In the story ‘Evidence’ she is asked to evaluate if electoral candidate Stephen Byerley is a human or a humanoid robot, bound by the Three Laws. Calvin admits this is not possible, as

“ … the three Rules of Robotics are the essential guiding principles of a good many of the world’s ethical systems”

She argues that every human being is supposed to have the instinct of self-preservation. That’s law Number 3. A good human, with a sense of responsibility, will defer to a proper authority, or Law Number 2. And every good person will protect his fellow human beings. That’s Law Number 1.

Calvin – or Asimov, we should say – concludes by saying that any being who follows these rules

“… may be a robot, and may simply be a very good man”.

Foundation

In the meanwhile, Asimov had also managed to tie the knot with Gertrude Blugerman on July 26, 1942. The couple had two children, David and Robyn Joan.

After the end of World War 2, Asimov was transferred from the Navy to an Army base in Oahu, Hawaii, which meant he had to face his greatest fear: flying. Taking to the skies was something he did only twice in his life, as Isaac preferred to treat himself to cruise ships when traveling abroad. After his honorable discharge at the end of 1946, Isaac returned to his studies, earning a Ph. D. in chemistry at Columbia University in 1948.

His income from writing was not yet enough to sustain a family, so in 1949 he accepted an offer from Boston University’s School of Medicine to teach biochemistry. Twenty years later, he confessed in an interview that

“I didn’t feel impelled to tell them that I’d never had any biochemistry!”

And yet he managed to teach it somehow! Not only that, he started writing textbooks about biochemistry. It was while writing one such book in 1951 that he finally realized that all he really wanted to do was write.

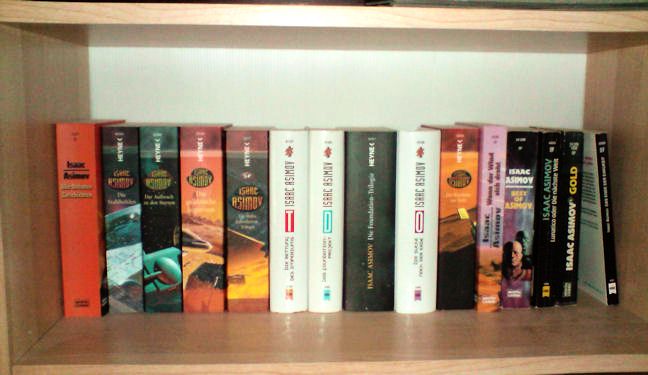

The year 1951 would prove significant, and not just because of this epiphany. That was also when one of his manuscripts was published as the novel “Foundation”, followed by “Foundation and Empire” in 1952 and “Second Foundation” in 1953.

This original trilogy was later expanded with four further prequels and sequels. Asimov himself acknowledged it would be his most enduring piece of fiction.

I am criminally over-simplifying now, but the series is about the decline of a Galactic Empire, after a rule of twelve thousand years. Mathematician Hari Seldon has created a new science called ‘psychohistory’, the use of mathematical modeling to analyze the aggregate behavioral data of an enormous number of people. This can help deduce the patterns of behavior of the masses. Essentially, Seldon is able to predict the Empire’s future, one marked by a dark age of ignorance and warfare that will last thirty thousand years.

To protect mankind’s knowledge, Seldon gathers the best minds of the Empire to a remote planet, a sanctuary which he calls ‘The Foundation’. Over the course of Centuries, the Foundation will expand, rivaling the decaying Empire, according to a master plan set in motion by Seldon.

The series is incredibly complex, spanning thousands of years and dealing with ambitious themes, such as the preservation of knowledge, the immortality of mankind via the propagation of ideas and the manipulation of the masses through religion. In 1966, the Foundation series won a special Hugo Award for Best All-Time Series in fantasy and science-fiction, snatching the prize from none other than The Lord of the Rings by JRR Tolkien.

Fans of both series should feel free to argue in the comments.

On Writing, Pinching, and Dating

So far, I have barely mentioned a fraction of Isaac Asimov’s body of work. The man was renowned for being incredibly prolific, and he improved with age. Here are some fun stats compiled by the New York Times:

Asimov wrote his first 100 books over the 20-year period spanning from the publication of his first short story until October 1959.

His second batch of 100 books took him about 9 ½ years. He had doubled his rate, and he kept accelerating. His third run of 100 books took him only 69 months, or less than 6 years. One may wonder: Did he ever suffer from writer’s block? What was his secret?

While it’s a pity that Asimov never published a book about writing, we can glean the secret of his success from a series of interviews and articles he released. This boils down to a mixture of genetics and good habits. Asimov remarked that,

“I have been fortunate to be born with a restless and efficient brain, with a capacity for clear thought and an ability to put that thought into words. None of this is to my credit. I am the beneficiary of a lucky break in the genetic sweepstakes.”

As per the good habits, Asimov woke up every morning at 6am, sat down at the typewriter by 7:30 and worked without stopping until 10pm. He never wrote more than two drafts of a piece of work: this was a self-imposed restriction to avoid lingering for too long on a piece he enjoyed particularly.

But those who dabble in writing know very well that the toughest bit can be to just start writing. Asimov never had such a problem. When asked if he had some form of concentration ritual to prepare for his writing session, he replied:

“Before I can possibly begin writing, it is always necessary for me to turn on my electric typewriter and to get close enough to it so that my fingers can reach the keys”

And once he started, he just kept ongoing

. Although he never really stumbled on a creative block, Asimov admitted to getting bored with the work at hand. In that case, his advice was simple: keep a number of open projects at hand, and immediately start writing about something else.

Regarding style, the author’s advice was to keep things simple:

“I make no effort to write poetically or in a high literary style. I try only to write clearly … I never read Hemingway or Fitzgerald or Joyce or Kafka. To this day, I am a stranger to 20th-century fiction and poetry, and I have no doubt that it shows in my writing.”

Despite avoiding the giants of 20th Century literature, Isaac Asimov was a voracious reader and learner, encouraging would-be writers to never stop accumulating knowledge, especially beyond a traditional school curriculum.

So, over the 1950s and 1960s, Asimov was cranking through his first 100 books, and his career was soaring.

But of course, this left little to no time to his family. By his own admission, he dedicated little attention to his children. And while he later recovered his relationship with his youngest daughter, Robyn, his rapport with eldest son David was always strained. David grew up to become a troubled and isolated individual — he achieved some notoriety in 1998 after being arrested on charges of possession of child pornography.

Back to Asimov in the 1950s. His marriage to Gertrude was deteriorating. In his memoirs, Asimov did not pinpoint a specific reason for their drifting apart: he blamed in part his wife’s smoking habit and even her rheumatoid arthritis. But in the end, he had to admit that it was the slow and natural process by which

“annoyances multiply (and) frictions come slowly to seem irreconcilable”

Eventually, the couple fell apart and formally separated in 1970.

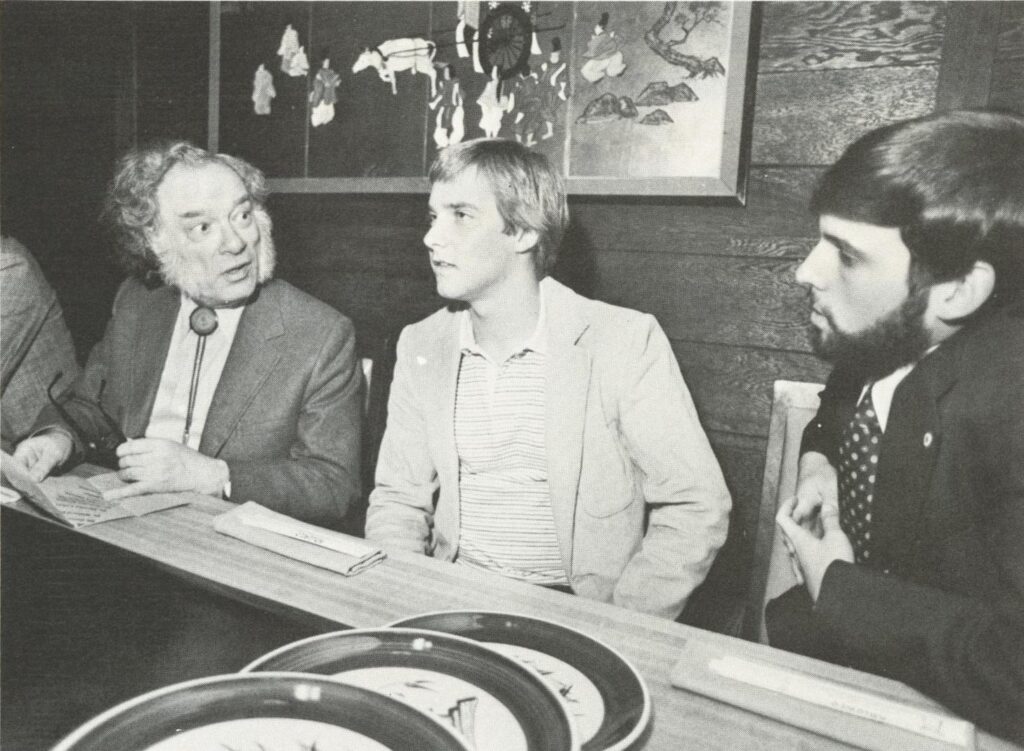

Now, while Asimov was happily married to Gertrude, he was described as being a model of moral rectitude by his friend and fellow sci-fi author Frederick Pohl. But the same Pohl noted that as soon as the cracks started appearing in the couple’s life, Asimov gave in to unwholesome behavior, to say the least.

During the frequent sci-fi conventions he attended from the late 1950s to the late 1960s, Asimov developed a reputation for being something of a sex pest. In plain terms, he had an obsession with groping the backsides of young and pretty participants at said conventions.

He was so renowned for his unwanted advances that in 1962 he was even invited to give a semi-serious talk at the World Science Fiction Convention on

“The Positive Power of Posterior Pinching”

He tentatively accepted the invitation, replying

“I have no doubt I could give a stimulating talk that would stiffen the manly fiber of everyone in the audience … I will have to ask the permission of various people who are (or would be) concerned in the matter. If they say ‘no’, it will be ‘no.'”

All this sounds like this may have been a different era, in which such behavior was more widely accepted, condoned, and even laughed about. At least, that’s what I learned from Mad Men.

However, even then, it was not a given that a young lady should tolerate unwanted physical attention from an older dude in a position of power.

Frederick Pohl, clearly equipped with a stronger moral compass, confronted Asimov about his bad habits, to which his friend admitted that he did get slapped a lot. And deservedly so.

Besides these incidents, literary conventions also provided Asimov with an opportunity for more meaningful human contact. Back in 1956, it was one at these events where Isaac struck a friendship with psychiatrist Janet Jeppson, a fan of his writing.

Their friendship continued by correspondence over the next decade. After Asimov and Gertrude separated, Janet helped him find a flat in New York … conveniently just a few blocks from her own. The two started dating soon after the move, and it eventually evolved into a serious relationship. When Asimov’s divorce was finalized in 1973, he and Janet were married only two weeks later.

Their marriage was a happy one, by all accounts and the two frequently collaborated. Janet wrote sci-fi novels for children, and Isaac worked as her editor.

Future Visions

Most of Asimov’s work during the 1960s and early 1970s was dedicated to non-fiction writing, including school textbooks, essays on Shakespeare, ancient Romans, ancient Greeks, and the Bible.

Due to his status as an author and scientist, he was frequently consulted about his vision for the future of humanity. In 1964, he published an article in the New York Times titled ‘Visit to the World’s Fair of 2014’, in which he gave some predictions on the next 50 years of human progress.

He correctly anticipated the market entry of self-driving cars, video calls, the widespread use of nuclear power, and simple robots that performed household tasks. Asimov also voiced his concerns about overpopulation, estimating that Earth’s inhabitants could number as many as 6.5 Billion by 2014. It was actually 7.1 Billion, so he wasn’t too far off!

Other predictions were a bit off the mark: for example, his expectation that underwater and underground housing would become the norm. Or that most transport would happen with hovercraft-like machines.

Finally, he prophesied that humanity would begin suffering “from the disease of boredom”, as a consequence of robotics supplanting most of our jobs. Maybe not a reality by 2014, but definitely a consideration for a not too distant future, as even yours truly may be replaced by an algorithm …

From the mid-70s to the 1980s Asimov returned to science fiction with a vengeance, writing four additional sequels to his magnum opus, the Foundation. In these sequels, Asimov manages to tie the events of the Foundation with those narrated in his Robot series, which, in that continuity, happened thousands of years previously. In this way, he creates an overarching macro-plot of celestial magnitude.

In 1974 Asimov dipped his toe into a genre completely alien to him: musical. The initiative came from former Beatle Paul McCartney, who approached Asimov with an idea for a musical movie. The plot devised by Paul was that a band discovered they were being impersonated by a group of extraterrestrials.

Asimov expanded it into an idea called “Five and Five and One.” In this story, parasitic aliens crash on Earth and are searching for hosts to invade. After trying out lizards, cattle and eagles, they decide to inhabit a group of musicians: the Beatles.

McCartney … hated this whole new storyline. Moreover, Asimov had ditched the dialogue written by the musician. The two potential co-authors parted ways, and the few pages that exist wait to be rediscovered at the Howard Gotlieb archives of Boston University.

A Legacy of Knowledge

In his later years, Isaac Asimov suffered from the onset of chronic heart disease, which required him to undertake a triple bypass surgery in 1983. Even though he recovered quite well, his health gradually declined over the following decade.

On April 6, 1992, Isaac Asimov died in New York, reportedly due to heart and kidney failure. At least, this was the official version, maintained by his brother Stanley, and by the New York Times obituary. Only in 2002 did the real truth emerged: after the 1983 operation, Asimov had received a transfusion of infected blood, contracting HIV and eventually dying of AIDS.

It is easy to quantify Isaac Asimov’s legacy today, through the sheer volume of books, articles and adaptations of his work. An asteroid and a crater on Mars have been named after him.

But he also left a legacy that is less quantifiable, an inspiration towards the accumulation and preservation of knowledge, a weapon of empowerment against ignorance and superstition.

“There is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there has always been,” he said. And I may add: not only in the United States! Asimov warned us:

“The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that ‘my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge’.”

SOURCES:

https://www.famousauthors.org/isaac-asimov

https://www.bbvaopenmind.com/en/technology/visionaries/the-lesser-known-side-of-isaac-asimov/

https://www.nytimes.com/1992/04/07/books/isaac-asimov-whose-thoughts-and-books-traveled-the-universe-is-dead-at-72.html?scp=7&sq=Asimov+Isaac&st=csehttps://biblio.co.uk/isaac-asimov/author/463

https://www.notablebiographies.com/An-Ba/Asimov-Isaac.html

https://interestingengineering.com/isaac-asimovs-biography-the-pebble-in-the-sky

https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/549054/isaac-asimov-facts

Nightfall and Religion

https://www.encyclopedia.com/education/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/nightfall

https://www.brainpickings.org/2013/08/13/isaac-asimov-religion-science-humanism/

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/dec/19/darkness-nightfall-isaac-asimov

Foundation and Psychohistory

https://vocal.media/futurism/asimov-101-your-ultimate-guide-to-the-foundation-series

Robotics

http://webhome.auburn.edu/~vestmon/robotics.html

https://www.robotshop.com/community/blog/show/fathers-of-robotics-isaac-asimov

Controversy

http://www.factfiend.com/isaac-asimov-kind-douchebag/

https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Charges-shatter-Asimov-son-s-reclusion-3099867.php

https://www.theregister.co.uk/2020/01/06/isaac_asimov_100_years_on/

Asimov and McCartney

Predictions and legacy

https://www.brainpickings.org/2013/08/13/isaac-asimov-religion-science-humanism/

https://interestingengineering.com/isaac-asimovs-biography-the-pebble-in-the-sky

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/asimov-predictions-from-1964-brief-report-card/

On writing

Works

http://archives.bu.edu/collections/collection?id=121382