Today’s protagonist was one of the key players on the giant chessboard that was Asia at the height of the Cold War. Born into a political family, she rose through India’s political system until she became the first and only female Prime Minister of her country. Her name was Indira Gandhi. In one of her speeches, she advised her followers to maintain a ‘bias toward action,’ or to encourage societal change, even if required painstakingly small steps.

Her life was definitely true to that principle: as the second longest-running Indian Prime Minister, Mrs. Gandhi won a war, oversaw the birth of a new State, broke the traditional non-aligned stance of India, and even made of her country a nuclear super-power. But it was her internal policies that made her mandate controversial, and eventually turned her into a target of hatred.

Welcome to today’s Biographics, in which we will look at the private and public life of Indira Gandhi, and how it all led to a fateful appointment with the very people who were meant to protect her.

Setting a good example

Indira Gandhi was born Indira Nehru on the November 19th, 1917, in Allahabad, in the state of Uttar Pradesh, India. She was the first-born child of Kamala and Jawaharlal Nehru, who were no ordinary family.

Kamala came from a conservative family of Kashmiri Brahmins — the category of priests and teachers, according to the traditional Indian caste system. This initially shy girl became an independence activist after meeting her future husband, Jawaharlal Nehru. Nehru was a well-educated lawyer and one of the most active members of the Indian Independence Movement, fighting for self-rule against the British Empire. As such, he was a close associate to the Mahatma Gandhi, and would later serve as the first Prime Minister of an independent India. While Nehru and Gandhi’s fight for independence through non-cooperation is widely known, Kamala’s role may have been overlooked.

Beginning in 1921, Kamala was actively involved in the Non-Cooperation movement, organising boycotts and picketing lines against shops selling British goods. When her husband was jailed by the colonial authorities, Kamala shed her natural shyness to deliver speeches to thousands of followers on his behalf.

With such fierce examples set by both her parents, it is no wonder that little Indira wanted to join the active struggle as early as possible. At age five, she carried out her first act of rebellion: she sacrificed her beloved doll – made in England – by throwing it onto a bonfire of imported British goods.

Two years later, in 1924, the Nehru family welcomed a second child, a boy, also born in November. Unfortunately, the newborn died after only two days, and Indira grew up as an only child.

In 1929, she escalated her commitment to the cause of self-determination. As a girl of only 12, Indira became a leader within an organisation numbering 60,000 young revolutionaries, called Vanar Sena, or ‘Monkey Brigade’. This name was inspired by the traditional epic Ramayana, in which an army of monkeys helps Prince Rama to defeat the despotic and monstrous Ravana. The Vanar Sena’s mission was less bellicose, but still dangerous, as it involved managing the communications and logistics that powered mass demonstrations and protests.

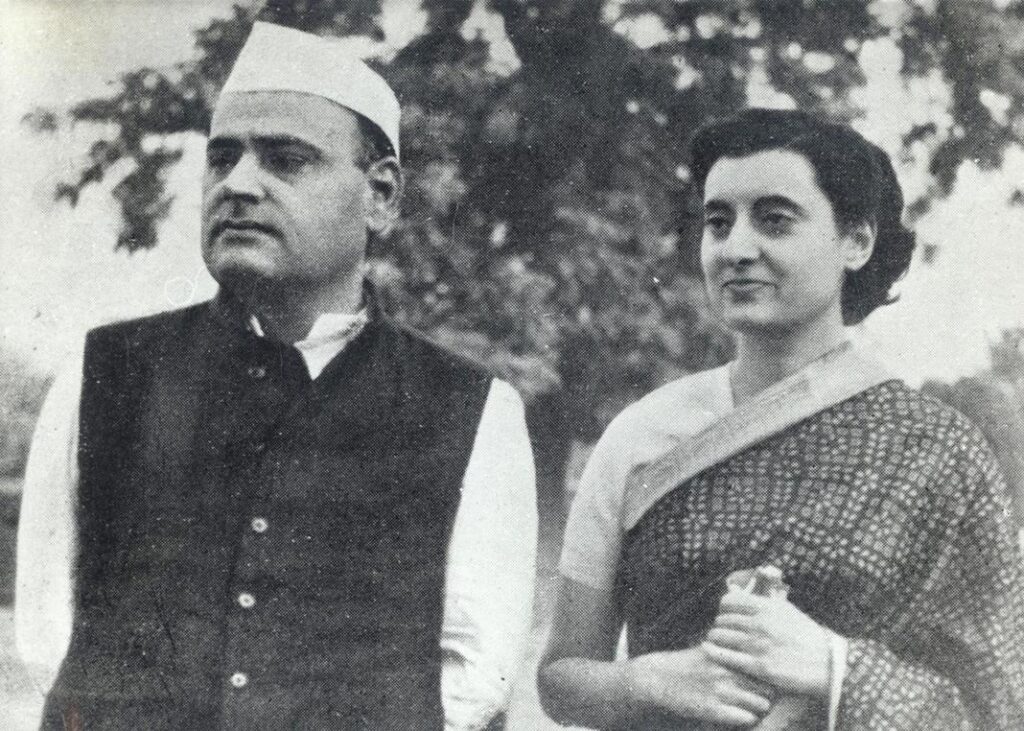

In March 1930, Indira and Kamala were participating in one of such protests outside Ewing Christian College in Allahabad. Indira’s mother suddenly collapsed, due to a heat stroke. An eighteen-year-old student of the College rushed to her aid. His name was Feroz Gandhi — no relation to the Mahatma. This chance encounter would prove one the most important for Indira’s life so far. Feroz became a good friend of both Indira and her mother, even helping to look after Kamala when she later contracted tuberculosis.

By 1936, Kamala moved to Switzerland to treat her tuberculosis, but this was in vain: she passed away on February 28, 1936, while her husband was in prison.

Shortly after her mother’s death, Indira traveled to Britain to enroll at Somerville College in Oxford to complete her studies. She never attained a degree, though, as her concentration may have been swayed by a big distraction, one that happened to be studying at the nearby London School of Economics: Feroz Gandhi.

Mrs and Mr Gandhi

Indira and Feroz rekindled their friendship, which turned into a courtship, and then into an engagement. Like Indira, Feroz was also well-educated involved in the independence movement, and he loved Indira. Despite all this, his potential father-in-law Nehru, objected to the union. Nehru simply had a personal dislike of the young Gandhi, and as father of the bride, he was entitled to a powerful opinion. As the Nehrus were a family under the spotlight, many ordinary citizens also chipped in to criticise the engagement, on the basis that he was a Parsi, not a Hindu like Indira, or that non-arranged marriages were not the norm. In fact, there was such a public outcry against the match that the other Gandhi, the Mahatma, had to offer a public statement of support, which included the request:

“I invite the writers of abusive letters to shed your wrath and bless the forthcoming marriage.”

Despite the objections and the abuse, Indira taught everybody a lesson in determination by marrying Feroz on March 26, 1942. Two years later, Indira gave birth to her first son Rajiv, followed in 1946 by Sanjay.

Unfortunately, this marriage was not a happy one. Feroz began having extramarital affairs almost immediately.

Things only got worse after August 15, 1947. This is the date in which Nehru became the first Prime Minister of an independent India, to which he added the title of Foreign Minister in the October of the same year. In this capacity, Nehru handled the first of many crises over Kashmir, a border region disputed with Pakistan. As work kept on piling up on Nehru’s desk, he enlisted his daughter Indira to help as his personal assistant. This was an unofficial role, although it became apparent to him and to the leadership of his party – the Indian National Congress, or INC – that Indira’s contribution was key to carrying out his functions.

Indira was spending more and more time with his father’s cabinet, eventually moving away from her hometown of Allahabad to the capital, Delhi. Her two sons followed her, while Feroz decided to stay back to concentrate on his work editing ‘The National Herald’ … but this arrangement also gave him free rein to pursue more clandestine liaisons.

During this de facto separation, Indira appeared to be completely absorbed by her administerial and political duties. This is probably the truth; however, we should mention that a book published in 1978 presents a different image. This is the autobiography of M.O.Mathai, Private Secretary to Prime Minister Nehru from 1946 to 1959.

The 28th chapter, titled ‘She,’ was removed from the final edition, but it has recently re-emerged thanks to Indian online media. According to the chapter, Indira tried to seduce Mathai in November 1947, and quite aggressively so. He yielded the day after, but due to being completely inexperienced, Indira had to first ‘educate’ him by giving him two books about sex and the female anatomy.

The chapter alleges that the clandestine relationship continued for more than 10 years, until the winter of 1958. While visiting Indira on urgent official business, Mathai caught her with another man, a yoga instructor.

This chapter may have not even been written by Mathai, and even if it were, Indira’s close associates strongly refuted these rumours. According to a former leader of the Indian National Congress, Natwar Singh, it would have been materially impossible for Indira to carry out some dangerous liaisons. According to Singh,

“It was just not possible for her to have an affair, there were security men under the bed! … Of course, you’re not made of wood but this is the price you pay – you don’t have a private life.”

First Steps on the Political Scene

Despite their marital issues, the Gandhis presented a united front in the arena of Indian politics. During the Parliamentary Elections in 1951-52, Indira became the campaign manager for Feroz. Indira clearly had a knack for campaigning and succeeded in securing a victory for her husband. After starting to serve as an MP, Feroz had to move to Delhi, but he did not join his family, preferring to live in a separate house.

From then on, both Gandhis made their bid to grow in status within the ruling party, the Indian National Congress, although admittedly in two very different fashions.

Feroz did so by exposing the corruption within his father-in-law’s government. He exposed a major scandal involving bribes paid by prominent insurance companies to the Finance Minister T.T. Krishnamachari. Because of this, Feroz began to emerge as the new rising star within India’s political circles.

On the other hand, Indira was following another route, rising from the inside of the INC party’s structure. In 1955, Indira first became a member, and then a president, of the working committee of the Indian National Congress — the inner circle that decided the party’s policies.

In 1958, Feroz suffered a heart attack during a state visit to Bhutan. Indira rushed him back to Delhi and took care of him for the following year. She still managed to advance her career within the party, and in 1959, Indira became President of the Indian National Congress.

Marred by poor health, Feroz could not match her rise, On the September 8, 1960, he suffered another cardiac arrest. This time, it was fatal.

The marriage of Indira and Feroz had not been the happiest. In addition to affairs and long periods of separation, their life was marred by frequent, vicious arguments. According to Indira’s biographer Sagarika Ghose, this was because both were extreme individualist, with an urge to dominate the other.

And yet Indira remembered those confrontations with fondness:

“I like to think that those quarrels enlivened our life, because without them, we would have had a normal life but banal and boring. We didn’t deserve a normal banal and boring life.”

Taking Centre Stage

Shortly after the death of Indira’s husband, her father’s health began declining. It did not help that in July 1962, India and China entered a War over some border disputes, which ended with a Chinese victory in November. Nehru’s conditions worsened, leading to his death on May 27, 1964.

Nehru was succeeded as Prime Minister by Lal Bahadur Shastri, who appointed Indira as Minister of Information and Broadcasting.

As a Minister, Indira proved very adept at building her image with well-planned publicity stunts, such as the one taking place during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965.

This confrontation over the control of the Kashmir border region took place from the 5th of August to the 22nd of September in 1965, when a UN resolution finally imposed a ceasefire. That summer, Indira planned a holiday retreat at Srinagar, in Kashmir. Despite repeated warnings by the security forces that Pakistani troops had advanced very close to her hotel, Indira Gandhi refused to move. The incident fetched her huge national and international media attention. It would take only a few months for Indira to take a role at the centre of the stage.

On the 11th of January 1966, Prime Minister Shastri died. Immediately, his fellow party members began squabbling and plotting to appoint a successor. The leadership of the Indian National Congress was by then split into two currents, one more conservative, the other with socialist leanings. These divisions made them unable to settle on a candidate, and so they started considering an appointment for Indira Gandhi. They had been led to believe that she was a goongi Gudiya, or ‘dumb doll’, easily manipulated. The perfect compromise candidate, then!

After much deliberation, Indira was chosen as the Prime Ministerial candidate by the Congress high command. Indira campaigned hard and emerged victorious on January 24, 1966.

At the age of 49, Indira Gandhi had become the Prime Minister of one of the largest and most populous countries on Earth.

She was not the first ever woman to be elected head of state or head of government; in fact she was only the third. The honour to be the first belongs to Khertek Anchimaa, Chairwoman of the Tuvan’s People Republic, from 1940 to 1944. The country was annexed by the USSR and does not exist anymore. The first-elected Prime Minister of a still existing country was Sirimavo Bandaranaike: in 1960, she became the head of Government in Sri Lanka, back then called Ceylon.

So, Mrs Gandhi may have not set a record in terms of timing, but she could wield an amount of power that her predecessors definitely could not boast. And that power was just about to increase.

From Strength to Strength

When Mrs. Gandhi was elected, the INC party was split in two opposing factions. Of the two, Indira sided with the socialist-leaning one. The INC was further weakened when new parliamentary elections took place in 1967, and the party lost 60 seats in the lower house.

In normal situations, this landslide defeat would spell the fall of the cabinet in charge. But the person in charge of the cabinet was not your normal Prime Minister. Indira Gandhi proved that her tenacity to cling to power was unparalleled. In order to ensure the survival of her government, Mrs. Gandhi went as far as forging a coalition with the Socialist and Communist Parties, something unthinkable a few years earlier, during her father Jawaharlal’s term in office.

Why do I say unthinkable? Nehru may have had a moderate interest in socialist political and economic reform, but in the context of the Cold War he definitely avoided siding with the Socialist Bloc. Nor with the Capitalist Bloc, for that matter. Nehru, alongside Egypt’s Nasser and Yugolsavia’s Tito, was one of the key leaders of the ‘non-aligned’ countries. While the world debated capitalism versus communism, India was mostly uninterested in taking a side.

Now, though, Nehru’s daughter and successor, far from being an easily swayed ‘doll’, was taking decisive action to steer India into a much clearer Socialist direction.

Domestically, in 1969, Mrs Gandhi’s cabinet nationalised the fourteen largest banks in India, as well as the four most important oil companies. Other reforms included the abolition of privileges for the Maharajas, who still held power in several of India’s States. Finally, Mrs. Gandhi initiated an agricultural reform based on the Green Revolution concepts developed by US Scientist Norman Borlaug: a combination of mechanised agriculture and development of new breeds of high-yield plants. Thanks to Gandhi’s reforms, India, normally beset by periodic famines, became an exporter of surplus rice and wheat.

As far as foreign policy goes, Indira Gandhi’s time in office was marked by tension and outright hostility toward China, Pakistan, and the US. At the same time, India signed a Peace, Friendship and Cooperation treaty with the Soviet Union in August 1971, marking a further drift away from equidistant non-alignment and towards the Socialist Bloc.

But let’s proceed in order.

The enmity with China dated back from the 1962 war and was exacerbated by Beijing’s nuclear tests in 1967. The shadow of this atomic threat prompted Gandhi to start pursuing India’s own nuclear program. Within just seven years, the country was able to perform their first underground detonation.

The rivalry with Pakistan over Kashmir was as old as India’s independence and had resulted already in two border wars. The two countries were about to enter a further conflict in 1971.

At that time, Pakistan was split into two separate territories, East and West Pakistan, separated by Northern India. Islamabad’s armed forces launched a violent counter-insurgency campaign in the Eastern half to suppress the Awami League, an independentist movement. The result of this internal struggle was that about 10 million East Pakistani citizens fled into India as refugees. The unprecedented humanitarian crisis stretched India’s resource to the limit, and it prompted Indira Gandhi to harshly condemn the repression on the 31st of March.

Soon, she started doing something more than just speaking sternly — Indira started supporting the Awami League in their independence fight. This was effectively a war by proxy against Pakistan, a calculated move to weaken the hostile neighbour and create a friendlier government on the North Eastern border.

Toward the end of the year, this local conflict took on regional, then international connotations. To put it simply

Pakistan did not like India.

China did not like India.

So, China supported Pakistan.

Enter a new player: the US.

China and the Soviet Union were not best pals anymore, so Nixon sought a rapprochement with Mao.

Ergo: the US liked China, who liked Pakistan. The US planned to help Pakistan, should India declare war.

All this implies that:

If China dislikes India, and

If the US dislike India,

India is going to make friends with a country those two also dislike: the Soviet Union. Hence the Peace, Friendship and Cooperation treaty I mentioned earlier!

In December of 1971, the conflict by proxy against Pakistan became a full-fledged war. On the 3rd of December, Pakistan decided to retaliate against India’s involvement with the Awami League by bombing Indian air fields in the western regions of Punjab and Kashmir.

The Indian government under Indira Gandhi had proven able to take quick, decisive actions, and the military was no different. The Indian air force retaliated on the 4th and quickly achieved air superiority. On the ground, the Army launched a quick attack into East Pakistan, converging on the regional capital, Dhaka. On the 9th of December, the war risked escalating beyond the Indian subcontinent, when Nixon ordered for a US fleet to head toward the theater of action. What may have happened, if the US provided direct support to Pakistan? We will never know: by the 16th of December, Dhaka had fallen to the Indian Army and the separatist forces of the Awami League.

The Indian victory in the third war with Pakistan was a personal triumph for Indira Gandhi, and resulted in the birth of a new nation: East Pakistan seceded and became Bangladesh. After the peace had been signed, the Prime Minister issued a clear warning in an interview with media, to powers both foreign and domestic:

“I am not a person to be pressured — by anybody or any nation.”

State of Emergency

The 1970s had begun well for Mrs. Gandhi, and she would soon score another triumph. In 1972, the INC faced the Socialist Party in national parliamentary elections. Gandhi’s party triumphed in the ballot boxes, thanks to the recent victory over Pakistan and to her campaign promise to eradicate poverty.

The defeated Socialist leader, Raj Narain, raised allegations of corruption and electoral malpractice. Soon, Socialist and other opposition parties took to the street, protesting against Gandhi’s government. As the decade progressed, Gandhi’s economic and social reform were largely nullified by rising inflation and a generally poor state of the economy. All this only played in the hands of protesters.

Narain’s charges were formalised with the High Court in Allahabad, who in June of 1975 ruled against the Prime Minister. Now Indira Gandhi was constitutionally expected to step down from office.

But she had already made it clear once: she wasn’t going to be pressured by anybody. As unrest spread throughout the country following the court ruling, Mrs Gandhi took this as the perfect occasion to declare a state of emergency, giving her extraordinary powers to rule by decree.

The period of emergency rule lasted two years, and it would be a black moment for Indian democracy. The country became a dictatorship in all but name: as an authoritarian ruler, Indira Gandhi ordered political opponents and other activists to be jailed, press freedom to be limited.

Indira’s main accomplice and confidante was her second-born son, Sanjay.

Taking advantage of extraordinary powers, Sanjay put into practice some pet projects of his: first, the forced removal of slum dwellings. More importantly, India enacted population control via forced sterilisation. This draconian measure was considered a necessary evil to allow for the country to prosper.

Indira’s government launched a campaign of vasectomies, starting with public employees: they were required to go through sterilisation to receive their salaries. The campaign was then extended to any male citizen, who would be offered cash, or even just cooking oil, as an incentive to accept a vasectomy.

Sanjay’s plans did not stop there: reports came out that vasectomies had been performed even on teenage boys, or that men were being arrested and sterilized. According to an exposé by TIME magazine, between April 1976 and January 1977, 7.8 million Indian boys and men were sterilized — well beyond the initial government target of 4.3 million.

At the beginning of 1977, Indira Gandhi put an end to the state of emergency by calling for new elections. The Prime Minister thought that all opposition had been effectively suppressed, and this would have been an easy win, one to legitimise her permanence in office. But I will take a guess here and say that one half of the electorate was not too keen on Gandhi. You know, the one half that doesn’t like their manhood to be messed with by forced surgery …

The elections resulted in a crushing defeat for the INC: they lost almost 200 seats compared to the previous legislature. The big winner this time was the Janata Dal, or ‘People’s Party’, a coalition of several smaller parties. Indira accepted defeat and stepped down.

Blue Star

Mrs Gandhi may have left office as Prime Minister, but she still held a seat in Parliament, from which she led the opposition against the Janata Dal. The new government tried to remove her by having her jailed briefly twice: in October of 1977, and then again in December of 1978. In both occasions, the charges were corruption.

But the plan did not work. As the tenuous alliance within the Janata started to crumble, the electorate called for stability – something that Indira and the INC could guarantee. New elections were called in January 1980, and Mrs Gandhi made a surprising come back as head of the Government. During the same elections, Indira’s son Sanjay won a seat in parliament. By May, Mrs Gandhi made it clear that he was her heir apparent by appointing him as secretary general of the INC.

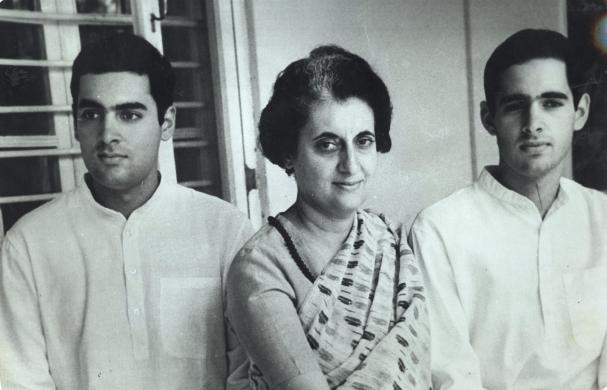

Sanjay’s rise had to stop abruptly June 23, 1980. For years Sanjay had been practising with some success in the sport of aircraft aerobatics. That day, too, Sanjay had gone out flying. But while performing aerial loops, he lost control and crashed with his plane, dying on the spot. Older brother Rajiv also had a passion for flying; until then he had not shown any interest in politics, working as a commercial pilot for Indian Airlines. But after this tragedy, Indira called him back into the fold of family politics. It was clear that she was building the Nehru-Gandhi dynastic line.

Indira expected the whole family to form a united front behind Rajiv’s budding political career, including Maneka, Sanjay’s widow. But Indira and Maneka had never got on well, and in 1982, a serious disagreement broke out between the two.

Maneka attended a rally held by Sanjay’s former political associates, which was perceived by the Prime Minister as a slight towards Rajiv. Indira ordered Maneka to leave the house in which the extended family all lived together. The daughter-in-law complied, but first she made sure the press was aware of her unfair eviction. Then, she separated Indira from hers and Sanjay’s son, Varun.

Not being able to see her grandson was a hard blow for the Prime Minister. As it turned out, it became one she could not recover from, as public troubles piled on top of the private ones.

By 1982, Mrs. Gandhi had to face the growth of secessionist movements all over India. Unrest flared up in the regions of Andhra Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, but the most serious threat came from the Sikh secessionist movement in Punjab, Northwestern India.

The movement was led by Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, who opposed peaceful negotiations with the government in Delhi. In July of 1982, Bhindranwale established his headquarters within the Harmandir Sahib, or Golden Temple, in Amritsar, Punjab. The Golden Temple is the most prominent centre of worship and pilgrimage for the Sikh faith: within its walls, Bhindranwale began recruiting supporters and amassing weapons for an armed insurrection.

Indira’s government grew more and more concerned about the Sikh separatist intentions, so eventually, in February1984, the Prime Minister decided to go on the offensive. The initial plan was to have airborne commandos kidnap Bhindranwale, but this was aborted in favour of a large scale occupation of the Golden Temple by Special Forces: ‘Operation Blue Star’.

Blue Star launched on the night between the 5th and the 6th of June 1984. The besieged Sikhs answered with heavy fire, including shooting RPGs at armoured vehicles, but after a night of fighting, the Indian commandos seized the Akal Takhat building, in which Bhindranwale had staged his last stand. The palace was hit by light arms fire, tank shells, and tear gas canisters: by 6am on the 6th, resistance had ceased and Bhindranwale’s body was discovered among the rubble. 83 troops lost their lives in the assault, versus 492 civilian fatalities. Some of these fatalities were Sikh separatists, but most were civilians. The majority of the dead were pilgrims who happened to be inside the temple at the wrong time.

Operation Blue Star was followed by Operation Woodrose, a larger military deployment which included infantry, armour, artillery, and helicopters confronting Sikh independentists across all of Punjab.

Both operations widened the rift between the Sikh minority and the rest of the country. Indira Gandhi’s prestige and popularity, which had made a recovery since the 1980 re-election, were heavily tarnished once again.

But something much, much worse than a dip in popularity was on the horizon for the Prime Minister.

On the morning of October 31st, 1984, Indira Gandhi was walking from her official residence toward her office to meet British actor Peter Ustinov, who was there to interview her for a BBC documentary. She was walking a few paces ahead of her attendant, as she approached the gates leading out of her gardens. At 9:09 am, Mrs Gandhi folded her hands to greet the two bodyguards stationed at the gates, Beant Singh and Satwant Singh.

These guards were not related. The Sanskrit word ‘Singh’ means lion, and it is an essential component of all male names among the Sikhs. It was only four months since Operations Blue Star and Woodrose, but the Prime Minister had no reason to mistrust her loyal Sikh bodyguards. In the case of Beant and Satwant, she had made a mistake: the two had been planning their revenge for the massacre at the Golden Temple.

Beant fired the first shots with his revolver, followed by Satwant, who fired his Sten submachine gun on full auto. Indira Gandhi was shot 30 times. She was rushed to a hospital, but her death was announced at 1 pm the same day.

The following day, ordinary citizens, in many cases aided and supported by police and local authorities, started a series of violent anti-Sikh riots, which resulted in the death of more than 3,000 Sikhs.

The death of a leader had sparked a period of unrest for her country – but that’s another story.

Legacy

Indira Gandhi had built her political career on the principle of bold action, independent from external pressure. This had led to successes like the Green revolution, the victory against Pakistan, the alliance with the USSR, and a stable nuclear programme.

Indira also succeeded in ensuring the continuation of the Nehru/Gandhi dynasty. Shortly after the assassination, her son Rajiv was sworn in as new Prime Minister. Rajiv remained in power for seven years, until he, too, was assassinated in May 1991 by a suicide bomber from aSri Lankan militant group, known as the ‘Tamil Tigers’.

In 1997, Rajiv’s wife Sonia was elected by INC members as their party President, a key role in setting the policies of the Country . Sonia Gandhi could have easily won over the seat of Prime Minister. But the fact that she is Italian by birth, did not allow her to cover official Government functions, let alone become the head of said Government. In 2017, Sonia continued the Dynastic tradition and handed over direction of the party to her son Rahul.

However, this was the story of a strong leader, and as usual, there are shadows behind the triumphs. It is not possible to overlook the excesses of the emergency years, the allegations of corruption, the poor management of the economy and finally the immediate and lasting effects of Operation Blue Star.