Being an island nation, you would figure that Great Britain would have its fair share of naval heroes. After all, the “wooden walls” of the Royal Navy protected the nation from invasion by various unfriendly Continental neighbors for hundreds of years, and then projected British strength across a globe spanning Empire that the sun never set upon.

But if you asked who the greatest of Britain’s naval heroes are, most people would give you the same answer. The humble son of an Anglican priest, Horatio Nelson rose to the rank of Vice Admiral while confounding and taking apart the French and Spanish navies sent against him, becoming one of the most famous men in the world in the process. He did everything he could to encourage that fame, relishing in his own success, but was also genuinely beloved by the people who knew him well and particularly the sailors who served under him. His style of leadership is still cited today in business and military leadership courses as highly effective.

Nelson’s death only added to his legend: killed with almost the last bullet in the greatest naval battle of the age, and one of the most famous in world history. Once again the Royal Navy had prevailed, frustrating the invasion plans of Napoleon and keeping British soil safe, but the death of Nelson at Trafalgar touched off a wave of national mourning that made many people question if it was worth it.

But before we tell you about his death, let’s tell you about his fascinating and complicated life first.

Early Life and Career

Horatio Nelson was born on September 29th, 1758, in Norfolk, England. His father, Edmund, was the parish priest of the small village of Burnham Thorpe. His mother Catherine’s brother, Maurice Suckling, was a captain in the Royal Navy, and young Horatio seemed destined for a naval career from the start. In 1771, aged only 12, Nelson became a midshipman, reporting to the ship HMS Raisonnable, captained by his uncle, to be trained as a naval officer. (In those days it was common for teenage boys to serve on Navy ships, in the days before military academies, it was figured that the best teacher for would-be officers was firsthand experience).

His early career was helped along by his uncle, who ensured that he was continually transferred to ships that were to see active service, so that Nelson rapidly gained more experience than his peers and was thus promoted quicker. In 1777, he was promoted to Lieutenant (Author’s Note: pronounced Left-ten-ant, but being British I figure you already knew that, Simon) and was assigned to HMS Lowestoffe, which was about to sail to Jamaica and to war.

First Taste of Combat

The rebellion of the Thirteen Colonies of America had quickly blossomed into a worldwide war, with the entry of France and Spain into the conflict on the side of the Americans. The Caribbean, where ships from all four belligerents routinely sailed, was a hotbed of naval activity. Nelson spent the next two years taking prizes (capturing enemy ships, the value of which was awarded to the ship’s crew as prize money), all the while being given more and more responsibility as his obvious talent became apparent. He was promoted to Captain in 1779, and early in 1780, Nelson captured a Spanish held fort on the San Juan River in Nicaragua, his first significant military achievement. His career was temporarily stalled when he was struck ill with malaria and was forced to return to Britain to recover.

Nelson soon returned to active duty in command of HMS Albemarle, which he commanded up and down the American coast until the war ended in an American victory in 1783. After the war, Nelson was sent to the Caribbean to act as a sort of policeman, seizing any American ships that attempted to trade with British colonial islands, which was illegal under the Navigation Acts.

It was during this time that he met Frances “Fanny” Nesbit, a widow who lived on a plantation on the island of Nevis. Nelson was smitten, and her uncle offered him a large dowry to marry her. It wasn’t until after they were engaged that Nelson discovered the dowry was a fiction, the family wasn’t worth anywhere near as much as they had claimed. To make matters worse, Fanny had hidden the fact that she was infertile, incapable of having children, until after they were engaged. Breaking off the engagement would have been dishonorable for an English gentleman, so Nelson had no choice but to go ahead with the wedding in 1787. The deception had soured the romance, however, and Nelson and Fanny would become more and more estranged as time passed.

Back in Action

In 1788 Nelson was sent home to Britain, and for 5 years he languished on shore without a command. With no war to fight, there simply weren’t enough ships to go around in the peacetime navy, and so Nelson was kept in reserve on half pay and absolutely nothing to do but tend to his affairs at home while continually badgering anyone he knew for a command.

He got his chance in late 1792, when the French Revolutionary government, eager to flex its might to its neighbors, annexed the Austrian Netherlands (modern day Belgium), which had traditionally been kept as a buffer state. The move heightened tensions between Britain and France, and in preparation for war, the Royal Navy called back its reserve officers, including Nelson, in January 1793. Soon after, France declared war, and Nelson’s ship sailed to Gibraltar in May as part of a fleet determined to establish British naval supremacy in the Mediterrenean. The flashpoint of the area was the French city of Toulon, which was held by French royalists but came under attack by the Revolutionary Jacobins. The city appealed to the Royal Navy for help, but eventually, a large republican force occupied the hills around the city and began to bombard it into submission. The artillery officer in charge of the bombardment was a young man named Napoleon Bonaparte, and this was to be the start of his own military success story, though no one knew it at the time.

Toulon fell in December, and seeking a naval base close to the French coast, the fleet commander ordered Nelson to blockade the French controlled island of Corsica, followed by an invasion in February 1794. After the army proved reluctant to proceed, Nelson himself was put in command of the land forces and helped capture the city of Bastia. He played an important role in ground operations for the remainder of the Corsican campaign, using cannons offloaded from naval ships to bombard enemy positions. On July 12th, Nelson was wounded by debris from an artillery round that exploded near one of his batteries, the wound eventually cost him the sight in his right eye.

Cape St. Vincent

After the capture of Corsica, Nelson spent the next three years engaged in operations in the Mediterrenean until French victories in Italy (at the head of an army commanded by Napoleon) forced the Royal Navy to leave their base in Corsica and sail to Gibraltar in December 1796.

Nelson was on the way to join them on February 1st, 1797, when, quite by accident, he happened upon the Spanish fleet that had left Cartagena and was heading south to the port of Cadiz to eventually link up with their French allies. Nelson’s ship, unseen in the fog, escaped to alert the fleet commander, Admiral John Jervis, of the Spanish movements. Jervis decided to give battle, and on Valentine’s Day, the two fleets met off of Cape St. Vincent.

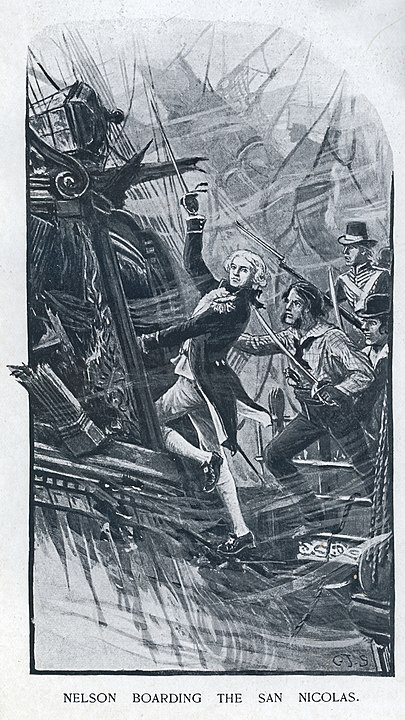

It was here that Nelson first distinguished himself in the eyes of the British public. In command of the ship HMS Captain, he engaged three much larger Spanish ships, and captured two of them by boarding them and engaging in vicious hand to hand combat.

The prize money from the two captured ships made Nelson rich, and his heroism at Cape St. Vincent had made him famous. He was now Sir Horatio Nelson, having been made a Knight of the Bath, and soon after the battle, he was promoted to Rear Admiral.

Wounding

One of the first things Admiral Nelson did after his promotion was to oversee a plan to capture the city of Santa Cruz de Tenerife in the Canary Islands, an important Spanish outpost and stopover point for the Spanish treasure fleets returning from the Americas. The plan called for a simultaneous bombardment and an amphibious landing. But after two aborted attempts to storm the beach, on the night of July 24th, 1797, Nelson decided to lead the troops ashore himself.

The resulting battle was a disaster for the British. The Spanish defenders were well dug in and they blasted the invading troops on the beach with cannon fire and musketry. No sooner had Nelson gone ashore than he was shot in the right arm and collapsed back into his boat. The musket ball had smashed his humerus bone in multiple places, and he was rowed back to his flagship to be attended to by the surgeon.

Medicine at the time period was barely out of the Dark Ages. Germ theory was still decades away, and the most common way to prevent a wounded limb from getting gangrene and killing the victim was to amputate it. Most of Nelson’s right arm was sliced off and thrown overboard. The rest of the British force didn’t fare much better: when they finally withdrew the next day, 250 had been killed, and another 128 wounded.

Nelson was despondent both over the failure to capture Santa Cruz and by the loss of his arm. He wrote to the commanding Admiral of the Mediterranean fleet that he intended to return home to England and retire, as, in his words “a left handed Admiral will never again be considered useful.”

Battle of the Nile

Nelson remained in England for several months, recuperating. But in March 1798, he went to sea again, having been convinced that the Royal Navy had use for a one armed Admiral after all, and that retirement didn’t really suit him anyway. He returned to the Mediterreanean, where he was given a squadron of 15 ships and ordered to Toulon to intercept a French fleet that was on the move.

In France, Napoleon Bonaparte had become the most important political and military figure in the country. His strategy for 1798 was to invade Egypt with a large army and navy and thus bring pressure to British occupied India, in the hopes that threatening her commercial interests would force Great Britain to abandon the war.

Napoleon got away from Nelson after the British ships were blown off course by a storm, but the British soon pursued them across the Mediterreanean to Alexandria. The French army had already won a series of victories against the ruling Mamluks and the French fleet was anchored off the coast of Alexandria in the delta of the Nile River in a supposedly impregnable defensive position. But Nelson was unimpressed and moved immediately to attack.

As dusk fell on August 1st, the British ships fell upon the stationary French ships. The French Admiral de Breuys had figured that the shoals on the flanks of his battle line would prevent the British from getting onto his starboard (right) side and thus surrounding him, so all of his sailors were ordered to man the port (left) side cannons. But Nelson’s lead ships found a gap in the shoals and suddenly the French found themselves under attack from both sides.

Darkness fell but the scene was illuminated by the battle raging in the Nile Delta. Cannons belched out flame from all sides, and started several fires, including one that engulfed the French flagship L’Orient, which exploded when the flames reached the gunpowder magazine, killing Admiral de Breuys. Admiral Nelson was wounded for the third time in his career, a flesh wound to the forehead that he had quickly bandaged and returned to oversee the battle.

Overwhelmed by the amount of British cannons brought to bear on them, the French ships began to surrender. As dawn broke on August 2nd, the battle was for all intents and purposes over. The French fleet was completely destroyed, out of 17 ships that began the battle, 4 were burned and 9 were captured. The French suffered 3,500 casualties to the British 900.

The battle had great strategic consequences for the war. It trapped Napoleon’s army in Egypt, forcing the general to return to France without his troops. He never trusted the navy again, and this mistrust would weigh heavily in his future military decisions. Great Britain, meanwhile, had gained complete dominance of the seas around the conflict zone, an advantage they’d hold for the rest of the war.

Emma Hamilton

Nelson’s victory at the Battle of the Nile made him a national hero. Heads of state from all over Europe sent him accolades and he reveled in the attention. For all his many virtues, Nelson was rather vain, and a shameless self promoter: for instance, when, shortly after word reached London of his victory he was given the title Baron Nelson of the Nile, Nelson was insulted that he was only given a “mere” barony instead of a more prestigious title.

Shortly after the Battle of the Nile, Nelson sailed to Naples to refit his squadron. He was feted by the Neapolitian royal court and was a guest of the British ambassador, Sir William Hamilton. Nelson had briefly met with Sir William and his wife, Emma in 1793, but he was a far different man now: scarred, blind in one eye, missing an arm, and internationally renowned.

Emma Hamilton was 35 years younger than her husband, and was considered one of the most beautiful and intelligent women of her day. During Nelson’s stay in Naples, he and Emma fell deeply in love with each other and soon were carrying on an affair that the entire world seemed to know about. The strange part was that not only was it apparent that Sir William was aware of his wife’s affair with Nelson, but he was surprisingly open-minded about it, considering the time he lived in. The three lived together in Naples and when Hamilton was recalled home to England, Nelson returned as well, and the three set up together at a house in London, much to the fury of Nelson’s wife Fanny. Around Christmas 1800 Fanny gave her husband an ultimatum, to choose Emma or her, and Nelson chose his mistress. The two never lived together again.

The Battle of Copenhagen

On January 1st, 1801, Nelson was promoted to Vice Admiral, and was sent on a new assignment to the Baltic Sea. Denmark, tired of Britain blockading her ports to stop French trade, had allied itself with Prussia, Sweden, and Russia to break the blockade of the Royal Navy. Nelson was sent as part of a fleet to break up this “league of armed neutrality” that threatened British naval supremacy in Europe. Nelson convinced his superior, Admiral Parker, to allow him to take a dozen ships of the line into Copenhagen harbor and attack the Danish fleet before they had time to join up with the Swedish and Russian fleets.

Nelson attacked on April 2nd. The battle didn’t start out well for the British: three ships ran aground early in the battle, prompting Admiral Parker to signal the retreat. But Nelson, who had a better grasp of the situation than Parker did, decided to continue the attack. In a bit of trademark wit, he held his telescope up to his blind eye and said “I honestly can’t see the signal.”

The battle soon turned in favor of the British, as they destroyed 3 Danish ships and captured and burned a dozen more. Nelson called for a truce, which the Danes accepted. The destruction of the Danish fleet, together with the sudden death of Tsar Peter I of Russia, marked the end of the League and Nelson returned home to receive more accolades. He was now Viscount Nelson of the Nile, and considered the country’s foremost naval hero.

In October 1801, Great Britain and France signed the Peace of Amiens, ending the war. Nelson spent the next two years in Britain, living with William and Emma Hamilton, and touring the country with them. Emma had given birth to a daughter, Horatia, that everyone knew was Nelson’s illegitimate daughter, and the unconventional family all lived together at a country estate in Surrey until Sir William died in April 1803. A month later, war again broke out and Nelson was back at sea.

Trafalgar

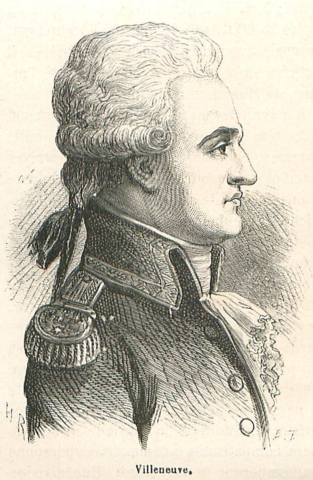

Nelson was appointed commander of the Mediterreanean Fleet and given the pride of the Royal Navy, HMS Victory, as his flagship. His orders were to blockade Toulon, where the French Navy under the command of Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve was at anchor. It was essential to keep the French ships from escaping the blockade and moving north to the English Channel, where they could help Napoleon, now Emperor of the French, invade Great Britain. For two years Nelson and Villeneuve played a cat and mouse game with each other, a series of back and forth maneuvers that saw Nelson at one point chase Villeneuve all the way across the Atlantic to the West Indies and then back again.

In August 1805, Nelson returned briefly to England on leave. He was cheered everywhere he went, much to his delight. In September, word came that the allied French and Spanish fleets had combined together at the Spanish port of Cadiz. Nelson knew it was time to return to sea. He departed on board Victory on September 14th, after saying goodbye to his beloved Emma.

Nelson arrived at Cadiz on September 27th, and spent most of the next month preparing for the battle he was sure to come. Meanwhile, his French counterpart, Villeneuve, was feeling the heat from Napoleon. The Emperor was angry that his Admiral wouldn’t engage the British fleet and break out of the blockade at Cadiz. He sent a replacement overland to Cadiz to take command of the fleet. Villeneuve, in an effort to stave off the humiliation of being relieved of command, decided to sail out before his replacement arrived. On October 20th, the 33 ships of the Franco-Spanish fleet sailed out of Cadiz and were spotted by British scout frigates, who quickly moved to inform Nelson.

On October 21st, Nelson moved his 27 ships to engage the enemy off the coast of Cape Trafalgar. At 11:45, he prepared to engage. He ordered his signalman to signal the rest of the ships in the fleet:

“England expects that every man will do his duty.”

A great cheer went up throughout the British fleet. Nelson was truly beloved by the men he commanded. In a time when naval officers were expected to be strict disciplinarians to the point of cruelty towards the common sailor, Nelson garnered respect with affection and kindness.

Nelson’s battle plan was simple: he meant to close with the Franco-Spanish fleet as quickly as possible, cut their battle line into three pieces, and engage the enemy in ship to ship combat, which he was sure he would be victorious at due to his superior trained gunnery crews. He split his force into two squadrons, one led by himself aboard Victory, and the other led by his second in command, Admiral Collingwood, aboard the Royal Sovereign.

With little wind to speed their progress, the British ships slowly moved towards the allied line, all the while under fire from the French and Spanish ships. Finally, after almost an hour, Victory passed between two French ships and fired a devastating broadside. Other ships followed and a general melee ensued. Victory found herself engaging the French ship Redoubtable. The French crew had largely abandoned their cannons and were massing on deck to try and board the admiral’s flagship, until they were cut apart by the cannon fire of a passing British ship. All the while, a murderous fire poured down from the Redoubtable’s mast and rigging from sailors stationed up there with muskets. Nelson had forbidden his captains from doing this, worried about the sails catching on fire. Thus unhampered, the French sharpshooters could pick their targets at will, and Nelson, standing on the quarterdeck in his distinctive uniform, made a perfect target.

At around 1:00 PM, an hour into the battle, Nelson was shot, the bullet entering through his shoulder blade and severing his spinal cord. The admiral collapsed to the deck, recognizing immediately that the wound was fatal. He was carried below deck and made comfortable, as there was nothing the doctor could do for him.

Nelson lived long enough to hear that yet another spectacular victory was his. The French and Spanish had lost 22 ships, the British had lost none. “Thank God I have done my duty,” Nelson said. The admiral died at 4:30, at the age of 47.

Aftermath

There was no celebration of the victory at the Battle of Trafalgar. Instead, the death of Admiral Nelson touched off a period of profound national mourning in Great Britain that wouldn’t be seen again until the death of Princess Diana nearly 200 years later.

Nelson’s body was returned to England and given a state funeral at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Thousands of people lined the funeral route and packed the pews of the cathedral to say goodbye to their hero.

One person not in attendance, however, was Emma Hamilton. Nelson had neglected to amend his will to include Emma and Horatia, and although he begged the country to take care of them before he died, Nelson’s brother, who inherited most of the estate, was completely uninterested in helping her. The British public may have been willing to overlook Nelson’s affair because of his status as a national hero, but after his death, Emma was branded an adulterer and was shunned by her former friends. She died in 1815 at the age of 49, deeply in debt and suffering from a number of health problems. Her daughter with Nelson, Horatia, lived a quiet life as a reverend’s wife and raised 10 children, living until 1881.

Nelson has had so many places and things named after him that it would be impossible to list them all. The most famous of these is Trafalgar Square in London, one of the most popular tourist spots in the city. Located prominently in the square is a 145 foot (44m) granite column, topped with a statue of the man who will likely forever be known as Britain’s most beloved sailor.