Several mythologies worldwide feature the mischievous presence of trickster gods. Stories and legends about these deities depict them as they sow chaos for the pleasure of defying conventional behavior.

Well-known examples include Loki, from the Norse pantheon or Anansi, in the West African and Caribbean lore. The function of these divine practical jokers is to propel change, to test the cohesion of the social order or to poke fun at the contradictions lurking behind an apparently functioning society.

When you imagine these tricksters, you more likely picture them wreaking havoc in a distant past, populated by fantastical creatures.

But what if I told you that Britain and Ireland had their own trickster God in the early 20th Century?

Born into high society, he mingled with poets, writers and politicians, but he made it his mission to poke fun at everything and everybody. His elaborate and sometimes cruel practical jokes raised outcry, scandal, and even parliamentary inquiries.

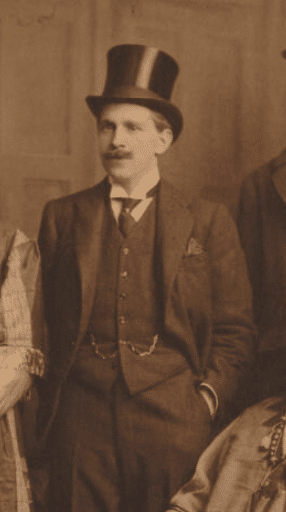

This is the story of Horace De Vere Cole, King of Pranksters, Patron Saint of April Fools’ Day.

The Boy of Ballincollig

Horace De Vere Cole was born on the 5th of May 1881, in Ballincollig, County Cork, in today’s Republic of Ireland, back then part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. His father was William Cole, a rich Englishman who had made a fortune selling quinine, a treatment for malaria. His mother was the Anglo-Irish aristocrat and poet Mary de Vere.

Throughout his early years, Horace was fascinated by both sides of his familial heritage. He idolized his father and his down-to-earth practical approach to life. But he was fascinated by the intellectual milieu frequented by his mother, steeped in Celtic and Irish mysticism.

Horace’s early years were generally happy. That is, until a bout of diphtheria left him partially deaf. This disability contributed to his social awkwardness and made him extremely sensitive to the criticism of his peers.

The boy could still count on his father’s love and support, the true bedrock of his childhood. Unfortunately, when he was just 11, he received the news that dad William had died of cholera, while on business in India.

When Mary remarried two years later, Horace felt betrayed and rejected. To add insult to injury, barely weeks after his mother’s second wedding, Horace was shipped off to Eton, the pinnacle of the British public school system. Which is ‘public’ only in name, being a private institution.

The boy hated this decision, well-aware that his deafness put him at a disadvantage.

He later wrote: “Why the devil, with such a handicap, was I sent to Eton where no deaf boy could hear anything in form? Callous cruelty … I call it. I should have been taught a trade or profession”

His school career was largely lackluster. Horace enjoyed the lessons and was rather popular with the other pupils. But he didn’t win any prizes, didn’t play any sports, and didn’t hold any position of responsibility.

Unsurprisingly, he decided to call it quits shortly before graduating.

In February of 1900, Horace left Eton. And like many young men of his generation, he volunteered to fight in the Anglo-Boer War.

In May of that year, he landed in Cape Town, with the distinction of being the youngest cavalryman in the entire British Army. Heavy losses in the officer corps propelled his career, and by the 2nd of July he had been promoted acting captain.

On that day, while riding back from a skirmish with the enemy, Horace failed to spot a Boer sniper hiding by the road.

The marksman took aim and fired, landing a direct hit on the young officer’s head.

Well, I hope you found today’s video interesting. If you would like to hear more biographies of men and women who changed the world, feel free to comment, like and subscr- Hang on … ?

Wait.

There’s more.

Of course there is.

Well, it appears that despite the marksmanship of the Boer, Army surgeons saved Horace’s life!

But the wound was too severe, and the young Cole was discharged and sent back to Britain. His military career had lasted barely three months, leaving him with a campaign medal, a standard army-issue mustache, and a pension of £2 per week.

Horace cashed in the entire pension in a lump sum: £1,800. In today’s money that’s £236,000, or $322,000. Displaying remarkable generosity, Horace donated the entire amount to the fund for war widows and orphans.

After fully recovering from his wound, Horace set about getting a place at Cambridge University. With the help of a tutor, he barely secured an entry and began his studies in October of 1902.

The fun times were just about to kick off.

The Bishop of Cambridge

At Cambridge, Horace hung around some promising students, people like:

Future economist John Maynard Keynes – later a friend of writer Virginia Woolf;

Or: Leonard Woolf – future husband of writer Virginia Woolf;

And: Adrian Stephen – current brother of Virginia Woolf. Obviously, Horace crossed paths with Virginia herself. She would later describe him as: “ … an Irishman … with beautiful blue eyes and a little mustache and perfect figure”

But more importantly “rather a dangerous friend for a young man to have … he was a wild young man. He was a bit of a scapegrace.”

Horace proved her completely right by joining clubs such as the ‘Magpie and Stump society’ and the ‘Cambridge Alpine Club’.

The former was named after a local brothel and its main pursuit was the consumption of alcohol.

The latter was dedicated to climbing the college roofs at night – presumably after the consumption of alcohol.

The hard-partying student also entertained political debate. Having been raised in a conservative household, he quickly converted to Socialism and became a proponent of the Fabian society, which advocated gradual reforms.

What really made him standout, however, was his love of pranks.

Some of his stunts were harmless.

For example, if a friend was ‘sent down’, or temporarily expelled, he would stage large fake funerals on the University grounds. On other occasions, he would dress up as a Bishop, showing up at schools and churches to perform confirmations and baptisms.

Other jokes were particularly cruel. Once, he entered a friend’s room at 3am and woke him up in terror, by shoving a dagger into the pillow.

Events such as this indicated that Horace had a darker side.

Biographer Martyn Downer speculates that Cole’s passion for practical jokes was a coping mechanism developed to cope with his deafness, with the death of his father, and with his mother’s rejection.

The injury suffered in the war, and the subsequent discharge, had been the final trigger. This was the last straw which would set Cole in a revenge path “against a world which had left him fatherless, deaf, and crippled by injury”

So, there was a darker side to the joker. Cole was known for sudden bouts of violence and reckless behavior, interspersed with melancholic spells. Downer even conjectured that Cole may have suffered from bipolar disorder.

According to contemporaries, and especially friend Adrian Stephen, Horace’s pranking was rooted in a disdain of established authority. In Adrian’s own words, the two agreed that “anyone who took up an attitude of authority over anyone else was necessarily also someone who offered everyone else a leg to pull”.

And during their second year at Cambridge, Horace and Adrian started looking for some serious legs to pull. They were looking for the perfect joke to humiliate the establishment. The tricksters came up with an exciting plan: dress up as German soldiers, travel to Alsace-Lorraine and then cross the border into France.

At the time, the two European powers were at loggerheads over control of Morocco. Such a stunt may have caused an international incident, even a war. The pranksters would have likely been shot!

Horace objected to the plan. Not for the reasons I just mentioned, but simply because it was too expensive!

The next best idea was concocted by Adrian Stephen, a sublime prank which went down in history as ‘The Sultan of Zanzibar Hoax’ or ‘the Cambridge Hoax.’

The Sultan of Zanzibar

The plan was set in motion when Adrian found out that the Sultan of Zanzibar was in London on an official visit. The pranksters set out a plan to humiliate the Mayor of Cambridge, a natural target due to the ongoing rivalry between the University and City authorities.

On the 2nd of March, Horace and Adrian sent a telegram to the Mayor, stating that the Sultan “will arrive today at Cambridge, 4.27(pm), for a short visit. Could you arrange to show him buildings of interest and send [a] carriage?”

Signed: Henry Lucas, colonial official.

Horace, Adrian, and their friends Bowen Colthurst and Leland Buxton disguised themselves in turbans, flowing robes, fake beards and black make up. A fifth cohort, known as ‘Drummer’ Howard, impersonated their English interpreter.

Whilst on the train from London to Cambridge, the party learned that the Sultan himself was due to visit Buckingham Palace that afternoon! Thinking quickly on his feet, Horace decided he would impersonate the Sultan’s fictitious uncle, Prince Mukasa Ali instead.

The pranksters were lavishly welcomed by the Mayor and his entourage, who gifted them a guidebook to Cambridge and a bottle of Champagne. Horace reciprocated by donating the dorsal fin from the “Sacred Shark of Zanzibar”

The party then proceeded to visit a local market, where disaster almost struck. An elderly lady, who had been a missionary to Zanzibar, accosted ‘Prince Mukasa’ and asked if she could converse in the local language.

‘Drummer’ the interpreter quickly stepped in, claiming that the Prince would talk to a woman only if she joined his harem.

After an official tour of the Guildhall and King’s College, the Zanzibarian dignitaries politely declined to stay for dinner and hastily returned to the train station.

The Mayor had been utterly duped, and his humiliation was complete when Adrian and Horace leaked the story to the papers.

On the 4th of March, the Daily Mail described the stunt as “One of the most audacious and carefully planned practical jokes ever perpetrated by undergraduates.”

The King of Jokers

When Cole emerged from Cambridge and into the real world, he did not feel the inclination to take up any serious profession. Well, any profession for that matter!

And in truth, he didn’t really need it. In 1906, his paternal grandmother died, bequeathing him a vast estate in her inheritance.

As Virginia Woolf wrote: “And so instead of going to the bar or becoming a man of business, he made it his business simply to make people laugh”.

And make them laugh he did.

Cole launched in a series of stunts designed to baffle and humiliate the staples of respectable British society.

For example, he would attend high society gatherings with a cow’s udder hanging from his trousers’ fly. When guests took notice of what looked like a protruding male appendage and gasped in horror, he would produce a pair of scissors, and cleanly cut it off!

Speaking of members, on another occasion he challenged Conservative MP Oliver Locker-Sampson to a race in a busy London street.

He graciously gave him a head start. But before the MP had started running, Cole slipped a golden watch into his pockets. As soon as Locker-Sampson started running, the trickster hailed a policeman and shouted ‘Stop! Thief!’.

The politician suffered the humiliation of being arrested and searched.

Cole frequently targeted police officers, to expose their haplessness. While riding on a cab, he frequently brought along the dummy of a nude woman. When the taxi passed near a ‘Bobby,’ Horace flung open the doors, slammed the dummy’s head on the road and shouted, ‘Ungrateful hussy!’ before driving off at high speed.

He further disturbed public order when he and a group of friends dressed as road workers and dug a trench in Piccadilly. Traffic was disrupted for hours, while policemen struggled to curb the ensuing chaos.

Other endeavors were exquisitely surreal, with a whiff of performance art. For example, once Cole organized a lavish dinner party for several guests who didn’t know each other. As they were waiting for the host, introductions were made. This is when they all realized they had the word ‘Bottom’ in their surnames!

On another occasion, he sabotaged a pretentious play in vogue in London. He bought several numbered tickets and handed them out to bald men. Thus strategically placed, their pates seen from the theatre balcony spelled a popular expletive.

A four-letter word, starting with ‘s’ and ending in ‘t’. Cole even took care of dotting the ‘i’.

According to another version of this prank, there were only eight bald men , and they all sat in the same row. But each had a letter painted on the back of their head, so that the audience could clearly read

“B-O-L-L-O-C-K-S”

Not all his practical jokes were so well-planned. Sometimes, Cole liked to improvise.

As a dead ringer for Labor leader Ramsay McDonald, Cole was frequently mistaken for him. Once, spotting a group of railroad workers, he introduced himself to them as the politician. To their dismay, he then launched into a tirade against the Labor movement and the dangers of Socialism!

None of these pranks, however, impressed public opinion as much as his masterpiece: The Dreadnought Hoax.

The Prince of Abyssinia

In early 1910, Cole was accosted by a junior naval officer who was engaged in a ‘duel’ of pranks against the officers of the HMS Dreadnought, pride of the Royal Navy. Could he devise the ultimate trick to humiliate his rivals?

Cole happily accepted, enlisting the help of Adrian Stephen.

Adrian happened to have a rivalry with his cousin William Fisher, also an officer on the Dreadnought. Of course he was game!

The two devised a plan similar to their Zanzibar Hoax, and assembled a team which included Adrian’s sister Virginia.

The parts were thus cast:

Horace would play the role of Herbert Cholmondeley, from the Foreign Office. Adrian was the interpreter.

Other four friends decked themselves again in turbans, blackface, and beards – including Virginia – to portray a retinue of Abyssinian dignitaries. They would be led by ‘Ras el Makalen’, supposed cousin of Emperor Menelik.

On the 10th of February 1910, a telegram was dispatched to Admiral May, Commander in Chief of the Home Fleet: “Prince Makalen of Abyssinia and suite arrive [at] 4.20(pm) today Weymouth. He wishes to see Dreadnought. Kindly arrange meet them on arrival.”

In a repeat of the Cambridge adventure, May and other high-ranking officers bent over backwards to welcome the foreign dignitaries, giving them an extensive tour of a state-of-the-art military facility!

The Abyssinian aristocrats admired the resplendent uniforms and the mighty guns of the Dreadnought, shouting in praise “Bunga! Bunga!” and other assorted gibberish.

When Adrian was asked to translate the Admiral’s speech during the tour, he mangled some words in Swahili – which was completely inappropriate – mixing them with Latin and Ancient Greek.

The Admiral invited the Abyssinians for dinner below deck, but Horace refused on their behalf, knowing that consuming food would have exposed the fake beards. As an excuse, he claimed that the Princes could not eat food that was not halal, and even asked if they could perform their Muslim prayers at sunset.

Small detail: Abyssinia – now Ethiopia- is a largely Christian country. And the hoaxers even wore large crucifixes!

The whole affair exposed how ruling classes at the time had little knowledge and consideration of non-European cultures.

After the hoax, Horace and Adrian once again revealed all the details to the press, causing an outcry. Public opinion sided with the pranksters, ridiculing the Royal Navy for their gullibility and carelessness. Admiral May was even subjected to a parliamentary inquiry!

This was a time when Britain was competing for supremacy of the seas against the German fleet … and the hoax had proven that it took only a telegram and some costumes to expose military secrets! Moreover, it emerged that May had squandered military funds for a large purchase of white kids gloves for the occasion!

‘A Jolly Good Fellow’

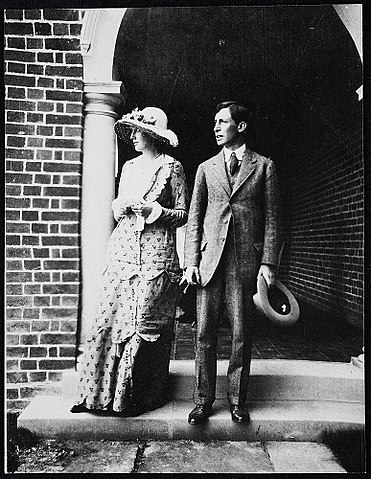

The year after the Dreadnought success, Horace’s sister Anne married a well-known public figure: future Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain.

Cole’s antics were a source of embarrassment for Chamberlain, and eventually also alienated his sister.

This may be why Cole took to spending less time in London, leading a debauched life in continental Europe, and later, in Dublin. During one of his trips to Ireland, Cole fell in love with young heiress Denise Ann Marie José Lynch. The two married on September 30th, 1918. He was 37; she was barely 19.

He later organized a honeymoon which suitably took them to Venice on April Fools’ Day 1919. He just couldn’t help himself: instead of enjoying the night with his young wife, Horace spent hours dropping horse manure all over Saint Mark’s square.

Again, a rather surreal stunt, carried out only to enjoy the look of confusion on the Venetians’ face. In a city notoriously devoid of horses, where had all that crap come from?

Once back in Ireland, the trickster had some close brushes with the ongoing independence struggle, with which Cole agreed in principle.

Nonetheless, he was still perceived as a member of the English oppressing aristocracy by the IRA. The Cole’s estate, Raford, was raided by the Republicans, who stole Cole’s best clothes and Denise’s jewels.

Subsequently, the Coles took residence in Dublin’s Shelbourne Hotel, where Horace spent the nights drinking with novelists and painters.

While there, Cole claimed to have identified and apprehended an English spy, who tried to mingle with the Republicans. He declared to have him arrested “for his own good, otherwise he would have been shot.”

Cole sent the alleged spy back to London, with a message claiming that the agent had been caught by legendary most wanted revolutionary Michael Collins.

Word spread that the trickster was somehow linked to Collins.

Or, possibly, that he was Michael Collins!

A dangerous rumor.

In fact, two days later, Cole was confronted by two ‘Black and Tans’, British members of the local constabulary with a reputation for brutality. The two officers were eager to cash the £5,000 reward for the capture of Collins.

Cole displayed a remarkable coolness when facing the Black and Tans, unleashing a secret weapon.

In his own words: “I produced some whiskey, and succeeded by lavish hospitality in reducing the men to a helpless state … They staggered away, saying that I was a jolly good fellow even if I was Michael Collins, and anyway what was £5,000 to them.”

The Ultimate Prank

In the late 1920s, Cole’s bouts of low, malicious moods took over his playful side. This aspect may have alienated his wife, although biographer Martyn Downer points out that they were ill-matched from the start.

He also became more direct and vulgar in his jokes. When the almanac ‘Who’s Who’ asked him to submit his entry, Cole filled in his ‘recreation’ as … well … ‘fornicating’ – but with less letters!

He was dutifully excluded.

Things deteriorated further in 1928, when Cole lost all his money in a bad investment in Canada. Denise took the occasion to ask for a dissolution of their marriage. Alone and almost penniless, Cole went on voluntary exile in France. While there, on the 31st of January 1931 he remarried with Mabel Wright, a scullery maid and former model to painter Augustus John.

On the 16th of March 1935, Cole and Mabel welcomed a baby boy, Tristan – later a TV director who also worked on Doctor Who!

Had Cole had access to the TARDIS, he would have turned back time to prevent Mabel from ever meeting Augustus John. It turned out that Mabel and the painter had been having a long-standing affair.

And Augustus John was the biological father of Tristan!

This was the ultimate prank that life had played on the greatest trickster of his age.

Heartbroken, impoverished, and forgotten, Horace De Vere Cole succumbed to a heart attack on February 26, 1936 in Honfleur, northwestern France.

And thus ends the story of the greatest of pranksters. He may have left a wake of laughter behind him, but darkness always lurked close, waiting to pounce on him when the end approached. A destiny he had in common with many a trickster god. Like Loki, condemned to imprisonment, misery, and torture.

But I don’t want to leave you on such a serious note. Horace would not agree. I will ask you instead to post in the comment what is the greatest prank you ever witnessed, or even better performed, to pull a leg at some pompous authority who had it coming.

SOURCES

General Biographies:

https://www.martyndowner.com/books/the-sultan-of-zanzibar/

https://www.historyextra.com/period/modern/how-to-carry-off-a-great-hoax/

https://thehistorianshut.com/2017/08/30/horace-de-vere-cole-the-great-prankster-of-britain/

The Sultan of Zanzibar: The Bizarre World and Spectacular Hoaxes of Horace de Vere Cole, by Martyn Downer:

https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/_/IYjkQgAACAAJ?hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiR37mZ0Kf1AhUDSvEDHUV7Am8Qre8FegQIBxAD

The Cambridge Hoax:

Reid, P. (1998). Stephens, Fishers, and the Court of the “Sultan of Zanzibar”: New Evidence from Virginia Stephen Woolf’s Childhood. Biography, 21(3), 328–340. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23540072

Cambridge Student Pranks: A History of Mischief & Mayhem, by Jamie Collinson

https://books.google.com/books?id=lQI7AwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=de+vere+cole&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=1&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiXhP7E0qf1AhV0mVwKHekSDDYQ6AF6BAgJEAI

The Dreadnought Hoax:

https://scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2022/21579/Marsh%20Bunga%20bunga%20dreadnought.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Johnston, G. (2009). Virginia Woolf’s Talk on the Dreadnought Hoax. Woolf Studies Annual, 15, 1–45. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24907113