In the early days of the 1980s, an unknown stalker was doing the rounds in the US, preying mainly on young homosexual men. One after the other, they fell victim to illnesses considered to be quite rare until that time.

Patterns began to emerge, leading to the discovery of a new infection, leading to a syndrome that would be dubbed ‘the Plague of the 21st Century’. A plague that would carry with it the stigma of behaviors considered by some to be morally reprehensible: HIV.

In today’s Biographics, we will trace the origins of the disease, from the first publicized cases in the US, to the later research pointing to the first outbreaks across the Atlantic. Along the way, we will discover the truth behind the man still known as ‘Patient Zero’.

The Unknown Stalker

HIV/AIDS were not easily identified at the start. It took time for medical researchers to piece together the clues that would lead to the identification of a new illness.

The first recorded event in that trail of clues was a Morbidity and Mortality report published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on June 5th, 1981. This report described five cases of a rare type of pneumonia — Pneumocystis carinii, or PCP.

This is a type of infection of the lungs caused by the fungus pneumocystis jirovecii, which leads to difficulty in breathing, high fever and dry cough.

The patients were young, previously healthy gay men in Los Angeles. All of them showed signs of severe immune deficiencies. Within days, doctors across the U.S. submitted reports of similar cases to the CDC.

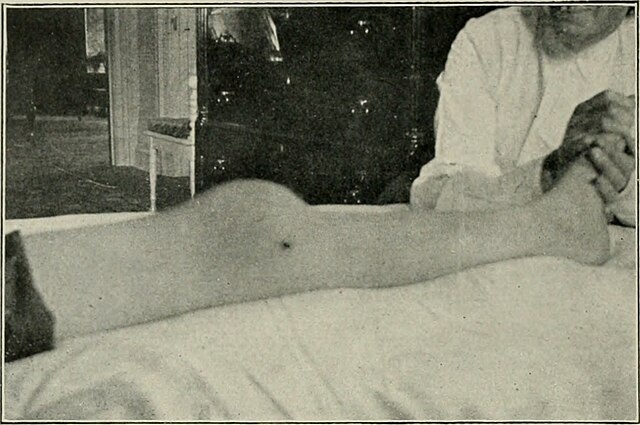

Less than a month later, on the 3rd of July, the New York Times published an article about an outbreak of a race cancer. 41 gay men in New York and California had been affected by Kaposi’s Sarcoma, an abnormal growth of small blood vessels that manifests itself with firm pink or purple spots on the skin. It can become life-threatening when it affects internal organs.

More and more homosexual men fell ill with rare conditions. Very often, these were associated with immune deficiencies.

In January of 1982, some of the patients and their friends and families founded Gay Men’s Health Crisis. This organisation would become the first non-profit, community-based HIV service provider … but at the time, they didn’t know what they were fighting against.

Very soon, it became clear that whatever was infecting US citizens was not only targeting homosexuals. On July 16th, 1982, a CDC report featured three cases of PCP in heterosexual, hemophiliac men.

Hemophilia is a genetic condition which prevents blood from clotting. In the 1980s, patients suffering from it required frequent blood and plasma transfusions.

Around the same time, the first cases of a new disease were being recorded in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Uganda, this disease was nicknamed ‘Slim Jim’, as it caused massive weight loss among its victims.

Later that year, the term ‘AIDS’ was first used to identify the new disease. It was the 24th of September when the CDC released the first definition of AIDS:

“A disease at least moderately predictive of a defect in cell-mediated immunity, occurring in a person with no known cause for diminished resistance to that disease.”

Gay men were the group among which the disease was most prevalent, but it quickly became apparent that they were by no means the only victims. In January of 1983, the CDC recorded the first two female patients. They were the partners of men living with AIDS, which suggested a sexual transmission of the disease.

Finally, in May of 1983, two teams of researchers found the cause behind this new illness.

The first team was headed by Dr. Françoise Barré-Sinoussi and Dr. Luc Montagnier, at the Pasteur Institute in France.

They isolated a virus which they believed responsible for causing AIDS, which they called LAV, or lymphadenopathy-associated virus.

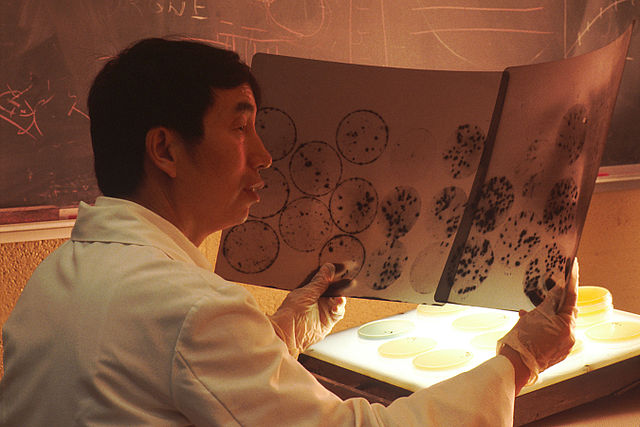

Later that year, Dr Robert Gallo of the National Cancer Institute in the US cultivated LAV specimens in his lab, identifying it as a retrovirus. This is a type of virus which can insert a DNA copy of its genome into a host cell in order to replicate.

In June of 1984, Dr. Gallo and Dr. Montagnier held a joint press conference announcing their discovery that a retrovirus was responsible for causing AIDS.

The French doctor called it LAV.

Gallo called it HTLV-III.

They later changed the name to Human Immunodeficiency Virus: HIV.

A Profile of the Stalker

The acronym AIDS stands for Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, and is the advanced stage of the infection caused by HIV.

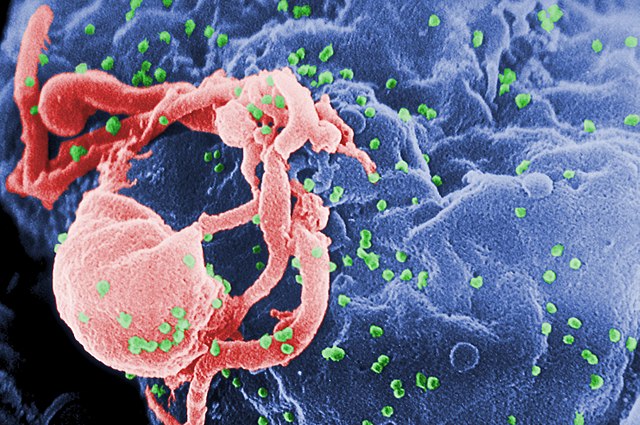

HIV is a rather aggressive virus which targets the cells of the immune system, making a person more vulnerable to other infections and diseases, which are often called ‘opportunistic infections’.

A healthy individual can contract HIV by contact with certain bodily fluids from an infected patient, with detectable viral load. Most commonly, this happens during unprotected sex, or through sharing injection drug equipment.

A person who is HIV-positive is considered to have progressed to AIDS when the number of their white blood cells of the CD4 type falls below 200 cells per cubic millimetre. Or, regardless of their CD4 count, when they have developed one or more opportunistic infection.

Title Baboon vs. HIV-I Description A scientist is screening a baboon virus and comparing it with HIV-I for similarities. Bacteriophage colonies are grown to determine whether there is a similarity in the two viruses and to discover the proper sequence of the AIDS virus. Topics/Categories Cancer Types — AIDS-Related Type Color, Photo Source National Cancer Institute

Opportunistic illnesses most commonly associated with AIDS, which can often lead to the death of a patient, include bacterial infections like salmonella, tuberculosis and pneumonia.

Less well-known consequences are fungal infestations, like thrush and PCP.

However, the weakening of immune defences brought about by HIV can also lead to the onset of certain types of cancer. For example, lymphoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma.

As of today, there is no cure for HIV. However, certain treatment regimens known as HAART, or Highly Active AntiRetroviral Therapy, can help patients live with HIV without it degenerating into AIDS. More on them later.

Without this therapy, people with AIDS typically survive about 3 years. Sadly, if they contract a dangerous opportunistic illness, their life expectancy falls to about 1 year.

Patients who are HIV positive can live for 10 to 15 years without noticeable symptoms. And even if they manifest, they can be easily mistaken for those of a less serious illness like seasonal flu.

When HIV degenerates into AIDS, common symptoms include rapid weight loss, diarrhoea, fatigue, memory loss, and depression.

Again, these symptoms are not exclusive to AIDS, and can be related to other illnesses. That is why the only certain way to diagnose HIV and AIDS is to get the appropriate test, to avoid an uncontrolled spread of the infection.

The most common ways through which HIV is transmitted are unprotected sex and the sharing of needles by drug users. But there are also other, less common avenues.

For example, a mother can pass HIV to her child during pregnancy, birth, or breastfeeding. There have been cases of health workers being infected when handling HIV-contaminated needles or other sharp objects, particularly if they are not utilizing the recommended Personal Protective Equipment.

A patient may also receive a transfusion of blood or plasma from a donor who was HIV positive. Nowadays, this risk is extremely low, because of the scrutiny that blood donations receive, but there had been many cases recorded in the early 1980s, before rigorous testing was put in place.

Finally, there is an extremely low risk of contracting HIV via oral contact. For example, if an individual is bitten by an infected patient. Or if two partners, both with bleeding gums or mouth ulcers share a deep kiss.

HIV absolutely cannot be spread by insect bites, physical contact, air, water, saliva, tears or sweat.

HIV can affect anyone regardless of sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, gender or age; however, certain groups are at higher risk for contracting HIV. The records of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that in the US certain demographics are more likely to get this virus.

According to 2018 CDC statistics, gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men accounted for 69 percent of all new HIV diagnoses. The next larger category was heterosexuals, accounting for 24% of new cases, followed by injection drug users, 7%.

Records also show that the incidence of new cases disproportionately affects ethnic minorities. For example, African Americans are about 13% of the overall population in the US, and yet, they account for 42% of the newly infected.

Hispanics are 18% of the population, but 27% of the HIV positive.

People who identify as ‘white’ are 70% of US citizens, but they are just a quarter of the overall incident patients.

All thing considered, gay African American men are the category at highest risk of contracting HIV, representing 25% of all cases.

[TITLE] The Stalker in the Open

Let’s go back to the 1980s now. It was becoming clear to medical professionals, and even part of the general public, that this new disease favoured certain groups, defined as ‘The Four H’s’:

Homosexuals, Heroin addicts, Haemophiliacs, and Haitian immigrants.

The first advocacy groups started to take shape in 1983. On May the 2nd, people with AIDS staged their first public demonstration, in San Francisco. In the following months, patient groups issued ‘The Denver Principles,’ a charter stating their right to be involved in policy decisions, and to be called “people with AIDS,” not “AIDS victims.”

On the 22nd of November, the World Health Organization held its first meeting to assess the global impact of AIDS. By this date, at least one case of the disease had been reported in each region of the world.

It took another couple of years before AIDS fully entered the public consciousness.

First, it was thanks to an Indiana teenager. On June 30th, Ryan White — a boy living with haemophilia — was denied admission to his local school. He had been infected with HIV from a blood transfusion.

Ryan went on to speak publicly against the stigma and discrimination that many AIDS patients experienced.

The other event was the death of Rock Hudson, on the 2nd of October. The legendary Hollywood actor died of AIDS, leaving $250,000 to help set up the American Foundation for AIDS Research, or amfAR. Fellow actress Elizabeth Taylor acted as National Chairperson for amfAR, which gave further boost to the disease awareness efforts.

The first few years of the epidemic, and their impact especially on the gay community, were recorded in the 1987 book And the Band Played On, by Randy Shilts, a journalist at the San Francisco Chronicle.

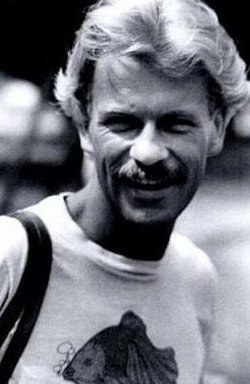

This book introduced a real-life character, a gay Canadian flight attendant who had succumbed to AIDS on March 30, 1984. Thanks to his good looks, charisma, and field of work, this flight attendant travelled across the country, having a string of sexual encounters along the way. Apparently, in a typical year, he could have up to 250 one-night stands.

While researching his book, Shilts also came across the ‘Cluster Study’, published in the American Journal of Medicine.

With this study, CDC investigators sought to draw a map of sexual encounters among several people with AIDS. The study featured a diagram, illustrating this network of relationships.

At the centre of the largest cluster, responsible for directly infecting eight patients, the paper had identified one ‘Patient 0’.

According to Shilts, this patient was ultimately responsible for introducing HIV and AIDS to the US.

For years after Shilts’ work had been published, a medical dictionary still referred to Patient 0 as, “an individual identified … as the person who introduced the HIV in the United States. According to CDC records, Patient Zero, an airline steward, infected nearly 50 other persons before he died of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in 1984.”

That ‘airline steward’ was the Canadian flight attendant we discussed earlier, and his name was Gaetan Dugas.

Patient O

Gaetan Dugas was born in Quebec City, Canada, on February 20, 1953. He worked for a period as a hairdresser in Toronto before moving to Vancouver. There, he realised his dream of becoming a flight attendant, working for Air Canada.

While on duty, he frequently travelled across Europe, the Caribbean, and the US, with his favourite destination being San Francisco. Gaetan loved to attend the annual pride parade, but he flew to San Francisco as often as he could, enjoying many of his sexual encounters there.

Gaetan was 26 when he first displayed symptoms of ill health — in this case, swollen lymph nodes. A year later, in 1980, brown spots appeared on his skin. Gaetan had them checked with a biopsy, which revealed he had Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Gaetan had to undergo several cycles of chemotherapy, with all the side effects that go with it, from inconvenient to agonisingly painful. Despite losing much weight and all of his hair, Gaetan continued to sport a cutting-edge look, wearing fashionable headbands and designer clothing.

But his sarcoma did not improve.

By this point, the clinical community had linked Kaposi’s to the new disease targeting homosexuals. It was referred to as ‘gay cancer’. In a letter to Ray Redford, a former lover and friend, Dugas described his mental state, as he tried to learn more about the disease, and to keep its symptoms at bay. He wrote:

‘My mind is finding peace again … You are right, I must upgrade my attitude towards a full recovery – but you know, there is always the storm that strike you when less expected’

The CDC started interviewing gay men with Kaposi Sarcoma, and soon realised that at least four of them had slept with Gaetan.

Dugas took part in this Cluster Study, too, cooperating eagerly and volunteering plenty of detailed information on the names and addresses of his previous partners.

The CDC made it clear to Gaetan that the new deadly illness may have been spread sexually. According to Shilts, in November of 1982, Gaetan Dugas was even confronted by a San Francisco public health official about his sexual habits.

Dugas was asked to avoid having sex to prevent further spreading of the disease, but he flatly refused.

It was his right, he said, to do what he wanted with his body.

By that time, Dugas had moved to San Francisco permanently, and he frequented the local bathhouses, looking for new partners. His success streak was such to rouse the jealousy of other gay men in the area. Some even conspired to have him evicted from town!

It was because of behaviors such as this, that Shilts harshly branded Dugas as

‘the Quebecois version of Typhoid Mary’

Eventually, Dugas left San Francisco and resettled in Vancouver. His body was now consumed by opportunistic infections, the most serious one being PCP – the fungal pneumonia.

The infection progressed inexorably. Gaetan moved back to his native Quebec City, where he passed away on March 30, 1984, aged just 31 years.

The Cluster Study was published some weeks after his death. All that remained of Gaetan’s lust for life was a circle, at the center of a diagram.

It was connected to eight other circles: LA 3, 6, 8 and 9; and NY 3, 4, 9 and 15.

Gaetan’s circle was marked by a ‘0’.

The only thing is … it was not a ‘zero’.

It was the letter ‘O’.

The Cluster Study marked its participant by location. Gaetan Dugas had been recorded as ‘Out of California’ – or simply ‘O’ for short.

Randy Shilts’ work had many critics, with Cambridge historian Richard McKay among them. McKay points out that Shilts had misunderstood the letter O for a number 0.

The diagram of the Cluster Study was not supposed to illustrate what may have been the epicentre of the pandemic in the US. It was intended to find a link between two outbreaks of Kaposi Sarcoma and other opportunistic illnesses — one on the West Coast, and the other on the East.

Gaetan – ‘O’ – and a certain ‘SF 1’ were the links between East and West. But Gaetan just happened to be placed at the centre!

Some of the other interviewees in the study were as promiscuous, if not moreso, than Dugas. But they could not – or would not – provide as many details as the Canadian steward.

Hence, his circle marked with an O appeared as more interconnected to other men.

That’s why it was easier to represent him graphically at the centre of the diagram.

Shilts’ editor, Michael Denneny, admitted that the two had overplayed the responsibilities of Dugas in the epidemic. In order to make ‘And the band played on’ more appealing, they painted Gaetan as the villain of the piece: Patient Zero, the ‘Typhoid Gary’ if you like, who had introduced HIV and AIDS to the US.

The intention was ultimately noble: increase circulation of the book, to raise awareness about HIV as well as stigma and indifference suffered by gay people with AIDS at the hands of authorities and the public.

But in doing so, ‘And the band played on’ created the false myth of Patient Zero, scapegoating Gaetan Dugas.

Even if the Canadian man was not an actual patient zero, Shilts’ book makes it clear that he stubbornly continued to spread HIV through unprotected sex. But that claim is disputed as well.

The CDC first stated that AIDS was sexually transmitted in January of 1983. Gaetan’s discussions with the CDC and the San Francisco health official took place in 1982.

Dugas’ behavior was certainly promiscuous; he definitely lacked caution, but it wasn’t as brazenly irresponsible as portrayed in the book. He was not consciously infecting as many men as he could.

What really matters to us is that HIV in the US did NOT start with Gaetan. It most likely cannot be traced to one single individual, and most likely did not start in the late 1970s or early 1980s. Considering that HIV can take as long as 15 years to display symptoms, many people could have been infected long before then.

In October of 1987, an article in the Chicago Tribune reported a story about tests run on samples belonging to a teenage male from St. Louis. The samples tested positive for HIV. And in fact, the individual had died from an AIDS-like condition … in 1969!

A ‘Nature’ article in 1990 found that tissue samples from a British sailor had also tested positive for HIV. He had died in Manchester from PCP … in 1959!

More clues pointed to an earlier origin of the disease, and to a location many miles away from North America.

In 1983, a joint Belgian and American research trip to Zaire – now the Democratic Republic of Congo – established that a disease similar to AIDS was widespread there, affecting mainly heterosexual men and women.

And in 1987, medical journal The Lancet found evidence of HIV-like infections in central Africa dating back to 1959.

Researchers were closing in on the place of origin of this plague of the 21st Century: Sub-Saharan Africa.

The Hunter and The Stalker

One of the most accredited theories on the origins of AIDS is the one dubbed ‘cut hunter theory’. One of their proponents is microbiologist Jacques Pepin.

In his 2011 work ‘The Origins of AIDS,’ he proposes a likely travel route from Central Africa to North America and the rest of the World.

HIV likely originated as a pathogen in primate populations, most probably chimpanzees. Late-stage infected chimps developed a syndrome called ‘SID’ – Simian Immuno-Deficiency.

Sometime in the early 1920s, the virus jumped species. This is when the virus somehow relocated from an infected ape, into the bloodstream of a human. The most likely candidate would be a hunter, whose open wounds were infected by the chimpanzee’s blood. The cut hunter, in other words.

In the 1920s and 1930s, French Equatorial Africa and the Belgian Congo enjoyed close trade and employment ties, meaning that any infected individual could have traveled across highly populated centers via short boat rides, spreading the disease further and further.

Pepin, in fact, found evidence of a disease similar to AIDS, causing an outbreak in a railway camp in French Equatorial Africa in the 1920s and early 1930s.

HIV may have spread via sexual contact, but also via iatrogenic transmission. These are infections caused by doctors reusing unsterilized needles.

Travelers and sailors visiting Central Africa may have contracted HIV as early as the 1950s.

However, Pepin was able to establish with more certainty a link between Zaire and the Caribbean. During the 1960s, several thousand Haitian were recruited to work in Zaire. It is possible that many of them became HIV positive and carried the infection back to their country.

From Haiti, HIV made it to North America via two avenues: the transnational blood industry, and sex tourism.

A study published in ‘Nature’ in October 2016 ascertained that blood and plasma collected from Haiti by a New York hospital was indeed HIV positive. Our Cambridge historian Richard McKay argues that Haiti was a popular destination for American gay men looking for sexual liaisons.

From these two entry points, the virus gradually spread to hemophiliacs, heroin users, and homosexuals. And of course, there are scores of potential Haitian immigrants, jumping the Gulf to the United States.. The ‘four H’s’ I already mentioned, in other words.

Through the efforts of Pepin, McKay and other researchers, it is clear now that the whole concept of Dugas as ‘Patient Zero’ is more or less debunked.

The first outbreak of what would be called AIDS dates back to at least half a century before, and it went completely undetected, before it swelled into what appeared to be an unstoppable pandemic.

Living with the Disease

Since the beginning of the epidemic, 76 million people have been infected with the HIV virus and about 33 million people have died of AIDS-related infections.

Luckily, advances in medical science have made it possible for HIV positive patients to live much longer than ever before. What used to be a fatal disease has now become a chronic illness: it cannot be cured, but it can be managed through the regular use of anti-retroviral drugs.

The first treatment indicated for HIV was approved by the FDA in 1987. In July of 1996, the 11th International AIDS Conference established HAART as a breakthrough approach, leading to a drop in morbidity and mortality.

Advances in other disease areas have also made it possible to prevent or treat the symptoms of the most common opportunistic illnesses.

However, HIV and AIDS are far from being completely defeated.

At the end of 2019, about 38 million people were estimated to be living with HIV across the Globe. During that same year, 690,000 people died of AIDS.

300,000 of them died in Eastern and Southern Africa alone.

Despite some advancements in treatment rates, Sub-Saharan Africa is still the region suffering the most from HIV. And amongst the infected, about three-fifths are women and young girls.

According to UNAIDS – the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS – the progress of the HIV crisis is related to the low supply of antiretroviral therapies. Naturally, this is a situation which may be exacerbated by the concurrent pandemic we are now living through, COVID-19.

But UNAIDS identifies another set of reasons: gender inequalities; lack of access to secondary education for girls; scarcity of sexual and reproductive health services. And there’s also the ongoing stigma which prevents HIV-positive people and at-risk populations from seeking treatment and preventative advice.

Now, we’ve mainly focused on the American HIV story, but here at today’s conclusion, I’d like to bring things closer to home. In 1987, millions of households in the UK received an informative booklet on the risks of HIV and AIDS. The booklet was tied to an effective TV ad campaign, and it used a frank language on the matter of transmission via sexual intercourse.

The tagline of this Department of Health campaign was ‘Don’t Die of Ignorance.’

It drove the point home. During any public health crisis, knowledge – and the responsible behaviour that grows out of it – are key.

As you’ve seen today, ignorance about the disease caused millions to die. But ignorance – and its brother, prejudice – can also isolate, condemn and taint the memory of those who don’t deserve it.

SOURCES:

The Basics of HIV and AIDS

https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3234451/

CDC Opportunistic Infections

https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/livingwithhiv/opportunisticinfections.html

CDC Incidence rates by population sub-groups

https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/statistics.html

https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

AIDS/HIV origins and history

https://www.healthline.com/health/hiv-aids/history

https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/history/hiv-and-aids-timeline

https://jech.bmj.com/content/67/6/473

https://www.nature.com/articles/nature19827

https://hivhistory.org/panels/panel-01/

The Story of Gaetan Dugas

https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v40/n18/tom-crewe/here-was-a-plague

https://www.scribd.com/book/414171918

https://www.scribd.com/book/240406939

https://www.scribd.com/book/362833379

HIV/AIDS Today in Africa