For thousands of years, Mesoamerica was one of the cultural centers of the New World. Civilizations such as the Olmec and the Maya left an indelible mark on America that influenced countless cultures that came after them. However, during the 15th century, it was all about the Aztecs. Their empire was the largest and strongest in Mesoamerica, and many of the smaller kingdoms and city-states were forced to pay tribute if they wanted to avoid the wrath of the Aztecs.

And then…the Spanish came, led by a conquistador named Hernan Cortes. Just two years later, the empire was no more: the people had been massacred or killed by disease, the capital of Tenochtitlan lay in ruins, and the last Aztec emperor was in chains. All to satisfy one man’s grand ambitions and his lust for gold.

Early Years

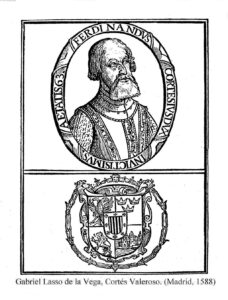

Hernán Cortés was born Hernándo Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano in 1485 in Medellin, a town in what was back then the Crown of Castile. His parents were Martín Cortés de Monroy and Catalina Pizarro Altamarino. Both were minor nobles with a distinguished lineage but empty pockets. This irked Cortes from a young age and the pursuit of fortune became a powerful motivator in his life, even an obsession, that guided most of his actions.

His parents hoped to provide Hernando with a cushy and respectable life, if not particularly lavish or exciting. That’s why they sent him to study in Salamanca when he was 14, perhaps hoping that he might become a lawyer, a lawmaker, or some other kind of legal official one day. It has been stated on occasion that Cortes gained a law degree from the University of Salamanca, but this doesn’t seem to be the case. All he did was some preparatory studies and an apprenticeship with a notary.

After two years of this, young Hernando had had enough. Much to his parents’ annoyance, he returned home with a desire to do something more exhilarating in life. Tales of adventure and riches in the New World had gripped Spain and Hernando was a 16-year-old with a rebellious spirit and a yearning to pursue fame and fortune.

Then, in 1501, the golden opportunity presented itself to Cortes. A distant relative named Nicolas de Ovando had been appointed as the new governor of the West Indies. He was going to sail to Hispaniola and was willing to take Hernando along. Fate, however, decided to keep Cortes in Spain a little longer. One night, after a romantic encounter, Hernando thought he would dazzle his ladylove by executing a daring leap from her window onto a stone wall. Which goes to show that, even back then, teenage boys did stupid things to impress girls. He landed on the wall, but it immediately collapsed beneath him and buried him in rubble. Therefore, on February 13, 1503, the Ovando expedition set sail for the West Indies as planned, but without Cortes who was in bed, nursing an injured back.

This delayed his plans for about a year. In 1504, the 18-year-old Cortes left Spain with Alonso Quintero, captain of the Trinidad, and headed for the New World.

Hispaniola and Cuba

Later that year, Cortes landed in Santo Domingo, the capital of Hispaniola. However, if he hoped that he would immediately be thrust into the middle of the action, he had another thing coming. In fact, the next years proved quite tedious for him, albeit useful. As a respectable and upstanding citizen, Cortes applied and received an encomienda. What exactly was that? It was a system used in the Spanish colonies where settlers received land grants alongside the legal right to forced labor from the natives. In exchange for this “fabulous opportunity,” the locals received military protection and were converted to Christianity. It was basically slavery with extra steps.

Besides running his plantation, Cortes also put his training from Salamanca to good use when Ovando appointed him as a notary of the new town of Azua. That was his life for the next seven years, but in that time, Hernando’s plantation brought him wealth and his position as an official made him connections. It was time well spent, but not exactly what he sailed across the Atlantic Ocean for. But he finally received the opportunity he was itching for in 1511.

During his time in Hispaniola, Cortes befriended a conquistador named Diego Velazquez who was tasked with colonizing the neighboring island of Cuba for more gold and slaves. In turn, Velazquez selected Cortes among the 300 men who would sail with him on the mission.

The expedition left Hispaniola in January 1511 and it only took it a few months to conquer Cuba. In that time, Velazquez and his men were responsible for several massacres, executions, tortures, and other unspeakable acts, which were documented by a friar named Bartolomé de las Casas who described all the atrocities in his work titled A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies.

The Spanish soldiers obviously had superior firepower, but they were also helped by the fact that the local tribes were not united against a common foe. Their biggest obstacle was a chief called Hatuey, who managed to gather a local resistance and conducted guerilla warfare against the invaders. But eventually, he was captured and burned at the stake. According to Las Casas, Hatuey was given the opportunity before his execution to embrace Christianity and go to heaven, but he said he’d rather go to hell so that he wouldn’t have to encounter any more Spaniards.

Although Cortes likely committed his fair share of vile deeds, we can’t give any specifics because Las Casas didn’t name any names in his account. Suffice it to say that Velazquez was deeply satisfied with his performance. After he became the first Governor of Cuba, he awarded Cortes with many land grants and slaves, as well as important government positions. In a short amount of time, Hernan Cortes became a rich and powerful man, but he still wanted more.

During his first few years in Cuba, Cortes, who was 20 years younger than Velazquez, became the governor’s golden boy. Velazquez even appointed him as the alcalde (aka a municipal magistrate) for Santiago de Cuba. However, as the years went on, Velazquez started getting a little wary of his protege. A rift developed between them around 1515, when Cortes promised to marry Catalina Suarez, the sister of one of his friends, but then got cold feet and tried to back out at the last minute. This didn’t sit well with Velazquez so he threatened Cortes with prison and even with deporting him back to Spain if he did not keep his promise. Ultimately, this persuaded Hernando to take the trip down the aisle in 1516. He was too ambitious and power-hungry to let an inconvenient marriage foil his plans.

Up until that point, Spain’s colonization efforts mostly focused on the Caribbean. However, now that Cuba was under its control, it was only a hop, skip, and jump away from the Americas. In 1517, an expedition led by Francisco de Cordoba sailed to the Yucatan Peninsula where they ran into the Maya who weren’t particularly happy with their arrival. A battle ensued and the Spanish quickly returned to safe Cuban waters. The next year, Velazquez sent another expedition led by his nephew, Juan de Grijalva. He was packing a bit more firepower; his mission wasn’t to fight the locals, though, but to explore the Mexican coastline. It is believed that his expedition was spotted by Cortes’s future opponent, the Aztec Emperor Motecuhzoma II, also known as Moctezuma or Montezuma. He is also someone we’ve already covered here at Biographics, just in case you want to hear about the conflict from the opposite point of view.

Anyway, once Grijalva returned from his scouting trip, Velazquez decided it was time for a proper expedition, one that would come back with plunder. And he had just the man in mind to lead it…Hernan Cortes.

Down in Mexico

Why exactly Velazquez selected Cortes for this opportunity is still a bit unclear. After all, the latter had little military experience. Maybe Velazquez genuinely thought that Cortes was loyal to him and would allow him to claim the lion’s share of the credit (and the treasure). Or maybe he simply underestimated him.

Whatever it was, Velazquez started to realize that he done goofed. Officially, the mission was simply to explore, convert natives to Christianity, and maybe do a little trade. But it soon became clear that Cortes was preparing for much more than that. He went all-in on the mission, mortgaging his estate in order to pay for the ships, the men, and the supplies. Before you knew it, Cortes had six ships waiting and an army of 300 men armed to the teeth parading with him around town.

This caused Velazquez to change his mind and revoke Cortes’s charter, but the latter would not be deterred. He left anyway in late 1518, in open defiance of Velazquez’s orders. He even stopped again in Trinidad and Havana to gather more supplies and soldiers. In February 1519, he sailed for Mexico with 11 ships, a hundred sailors, over 500 soldiers, sixteen horses, and over a dozen cannons.

Cortes first landed on Cozumel, an island off the Yucatan Peninsula which was inhabited by the Maya. This little detour went mostly peacefully, even when Cortes ordered his men to destroy the Mayan idols and replace them with a cross and a statue of the Virgin Mary. Imagine his surprise when he was approached by a man speaking Spanish. His name was Jerónimo de Aguilar and he was a Franciscan friar who got shipwrecked and captured as a slave eight years earlier. His fellow survivors were all either sacrificed or worked to death, but Aguilar managed to escape and spent that time with another, less murder-y tribe. Now, however, he was eager to join up with Cortes’s expedition and, as a terrific boon, he could speak the Chontal Maya language and could act as interpreter.

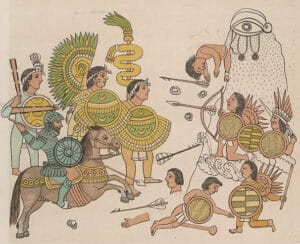

On March 12, 1519, Cortes and his men touched ground in Mexico proper, at the mouth of the Tabasco River. The nearby town of Tabasco became his first target, although initially, he attempted to trade with them peacefully. The locals weren’t having it, though, and before you knew it “the whole bank was thick with…warriors, carrying their native arms, blowing trumpets and conches, and beating drums.” They had the fighting spirit, but they were simply outgunned. It was arrows and darts versus metal armor and cannons and the battle was soon over…but not for long. Several tribes banded together and amassed a large army, one which supposedly outnumbered the Spanish 300-to-1.

Despite the massive size advantage, the natives simply had never encountered an army like that of the Spanish. A combination of cavalry attacks and cannon fire caused a large number of initial casualties and prompted everyone else to flee in panic. It was a resounding victory for Cortes – 800 Tabascans were killed versus two Spaniards. However, it was not one that he would be able to replicate indefinitely. He knew that he did not have the manpower to maintain control over all the new lands he intended to claim for Spain, so some kind of diplomacy had to be involved.

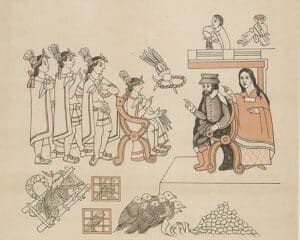

Cortes held a meeting with 30 local chiefs. Gifts were exchanged, the conquistador allowed the locals to collect and bury their dead, all the while ensuring them of his peaceful intentions. They did have to convert to Christianity, though. This was a sticking point for Cortes. By this point, the native tribes were in fear and awe of the Spanish army, so they complied. They even gave Cortes 20 women as slaves and one of them was particularly relevant. Her name was Malitzen or La Malinche and she not only spoke Mayan, but also Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. Once she learned Spanish, as well, she became a massive upgrade over Cortes’s previous interpreter. Eventually, she would become the conquistador’s mistress, given the honorific title Doña Marina, and even bore his first son, Martín Cortés.

For now, Cortes was ready to continue his journey. He kept asking everyone about gold and they all gave him the same answer – if it’s gold you’re after, then the Aztecs are the ones you want.

The Road to Tenochtitlan

Cortes had founded the city of Vella Rica de la Vera Cruz on the coast and established a garrison there. Remember that this entire expedition was, basically, an act of mutiny against Velazquez, and Cortes thought that he could skirt the rules by establishing a new territory for Spain and putting himself in charge. That way, he was completely outside the authority of the Governor of Cuba and reported to the king directly. Cortes even wrote to King Charles V and told him what he had done, albeit leaving out a few minor details. Basically, Cortes was gambling his freedom, even his life, that this expedition would be worthwhile enough to the king that he wouldn’t care about the “misunderstanding” in Cuba.

Word of the Spanish expedition reached Montezuma inside the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan. He was disheartened to hear about the might of their arsenal, particularly their cavalry and cannons, two elements that the Aztecs had never encountered in warfare before.

The Spanish and the Aztecs met for the first time around Easter. Montezuma did not travel himself and, instead, sent emissaries with loads of gifts, most of them out of gold and silver which, really, was about the worst thing he could have done. That was like catnip for Cortes.

The Aztecs were represented by a man called Tendile. The two sides met multiple times. Each encounter was cordial – Cortes and Tendile kept exchanging gifts and sharing information about their cultures – but there was definitely some heavy tension beneath the surface. Cortes made no secret about his lust for gold. His secretary wrote that the conquistador told Tendile “I and my companions suffer from a disease of the heart which can be cured only with gold.” Cortes made his wishes clear – he wanted to travel to Tenochtitlan and meet with Montezuma. He was told this was impossible and, eventually, the two sides broke off all contact.

Now Cortes had to decide his next move. Already, the Aztecs filled his coffers with more gold than anyone expected. He could have returned to Cuba and would probably be fine, maybe? That’s what many of his men wanted to do. But Cortes had too much ambition to stop now. It was all or nothing for him so he decided to march on Tenochtitlan. Before all that, he burned his ships, but only metaphorically, not literally, despite the legend. Cortes never actually burned any ships, but he did have them scuttled and then dismantled. This was to salvage any valuable components for the trek ahead, but also to prevent some of his more disgruntled companions from returning to Cuba.

The expedition stayed in Veracruz for about four months and this was time well-spent. Scouting parties discovered that the Aztecs weren’t particularly popular in those parts. Many other indigenous people such as the Tlaxcalans were kept under their thumb and forced to pay tribute. They might have been wary of the Spaniards; some even battled them when they first encountered them. But the old adage of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” rang true and they could not pass up the opportunity to fight their greatest foe.

Unfortunately for the people of Cholula, they were the ones who bore the brunt of their wrath. At first, the Spanish were greeted kindly, but this was all a ruse to lure them into an ambush. However, Malitzen discovered the treachery and told Cortes who decided to turn Cholula into a bloody message for Montezuma. He gathered the locals in the town square and a deadly massacre ensued, starting with the Cholulan chieftains, who were known as caciques. Spanish and Tlaxcalan alike roamed the streets of the city, killing anyone who got in their way and setting the houses on fire. Once the bloodbath was over, Cortes marched on to Tenochtitlan.

Fall of the Aztecs

News of the failed plot and its horrific consequences reached Montezuma and, even though he was the one who ordered it, he still extended a peaceful invitation to the Spanish, likely to stall for time or to study his enemy up close. And that’s how in November 1519, Hernan Cortes entered Tenochtitlan unopposed.

Both Cortes and Montezuma behaved amicably, but this was just for show. They shook hands with the right while waiting to stab each other in the back with the left. It was just a matter of who would do it first and, seemingly, it was Montezuma. After a few days in Tenochtitlan, word reached Cortes that the Aztecs launched an attack on their remaining forces in Veracruz. Once again, it was time for him to take a big gamble, so Cortes and his men walked into the palace and took Montezuma hostage. Strangely, the Aztec king went along without a fight, and why exactly he did this is still up for debate. It’s unlikely that he just gave up his empire because Cortes asked nicely.

Cortes ruled over Tenochtitlan with Montezuma as his prisoner for almost six months, collecting a gigantic treasure that he intended to take home with him. Then the conquistador had another danger to face. Velazquez finally decided to get involved and he sent a new expedition of 1,000 Spaniards led by Pánfilo de Narváez to punish Cortes for his treachery and they were headed for Tenochtitlan. Cortes decided to leave 120 men in the city, led by Pedro de Alvarado, and take the rest to take on this new threat. He was banking on the fact that knowing the terrain gave him the advantage. And he was right…Cortes mounted a surprise night attack during heavy rain and, within an hour, Narvaez was his prisoner and the battle ended with few casualties on both sides. Even better was that most of the opposing army joined him once they found out how much gold there was to be had.

Unfortunately, things weren’t going so well back in Tenochtitlan. Alvarado didn’t have his predecessor’s cool temper or charisma. He was nervous and he was worried that Narvaez had defeated Cortes and that no reinforcements were coming. Eventually, when the Aztecs stopped delivering them food, Alvarado assumed that an attack was not far behind, so on May 22, 1520, he launched a preemptive strike by massacring all the Aztecs who had gathered inside the Great Temple for a celebration.

When Cortes returned to Tenochtitlan, the city was in chaos, and not even Montezuma could calm spirits anymore. The Aztec king was killed during the fighting, although who did it and how remains uncertain (the Aztecs blamed the Spanish, the Spanish blamed the Aztecs). He was succeeded by his younger brother, Cuitláhuac, who knew there could be no peace with the Spaniards. Left with little choice, Cortes made a difficult choice: his men abandoned most of their treasure, and on the night of July 1, 1520, dubbed La Noche Triste, they tried to escape the city.

Of course, the Aztecs were not far behind, and the Spanish rearguard had to constantly fight them off. This culminated in the Battle of Otumba on July 7, and even though the Spanish were victorious, they had sustained over 800 casualties by the time they reached safety in Tlaxcala.

Cortes had no intention of giving up and fortune smiled upon him once more. As he was licking his wounds, several ships full of supplies and reinforcements started arriving in Veracruz. Some were from Velazquez, who assumed that Narvaez would be in control by now. Others were from Jamaica and one even came from Spain. All the men were persuaded to join Cortes, either with gold or the sharp end of a sword, and, before you knew it, the conquistador had an army again. In June 1521, he was ready to march on Tenochtitlan again. This time, no more fake smiles and pretend friendships. Everyone knew it was an all-out war.

The Aztecs fought bravely and viciously, but they were outmatched. Each day, the Spanish made a little more progress, and Cortes ordered each new bit they gained to be destroyed so that the Aztecs had nothing to win back. After two months of this, most of Tenochtitlan was in ruins, and one final bloody push ended the war on August 13 as the Aztecs made their last stand.

Life After

The once-mighty Aztec capital lay in ruins as tens of thousands of corpses were strewn through the streets. Fires burned day and night to get rid of the bodies, but the stench was still so overpowering that the Spaniards camped well outside the ruins of Tenochtitlan. Cortes had conquered the Aztec Empire for the Spanish crown, but every day he searched in vain for the one thing he truly coveted – the massive treasure that he left behind during La Noche Triste. That was nowhere to be found and still is missing to this day, becoming one of history’s fabled lost treasures.

One smart thing that Cortes had done was to save as much as possible from the share of the treasure that he intended to give to the king. The monarch was appeased enough to name Cortes the governor and captain-general of the Spanish Empire’s new colony, creatively titled New Spain.

This position didn’t last long, though. Cortes’s way of doing things might have brought him success, but it also made him plenty of enemies who undermined his authority to the king. First, they convinced Charles V that Cortes wasn’t sending back his fair share of the riches, so the monarch sent his own men to New Spain to determine just how wealthy his new colony was.

Then, in 1524, Cortes got Velazquezed. He had sent one of his trusted men, Cristóbal de Olid, to conquer Honduras, but the latter decided to claim it for himself, just like Cortes had done in Mexico. Angered by the betrayal, Cortes set off for Honduras, and, although he managed to defeat Olid, when he returned to Mexico he discovered he was no longer governor. While he was gone, his enemies persuaded the king to assign a commissioner to investigate Cortes’s conduct, and he decided to remove the conquistador from office.

Cortes spent the next half-decade of his life trying to regain his authority but with no success. He returned to Spain where the king received him with full honors, confirmed his massive land holdings, and even made him a don, but no governorship. That became a running theme for the latter part of Cortes’s life. People showed him deference and honored his achievements, but were wary to give him any significant power. In 1930, Cortes returned to Mexico, where he mostly dealt with administering his numerous encomiendas. He funded multiple exploration expeditions and, every now and then, he’d get the itch to join them, most notably the one to Baja California.

His last adventure came in 1541 when he joined an expedition to Algiers led by King Charles himself to fight pirates. However, when the king didn’t invite Cortes to join his War Council or, at least, seek out his advice, it only served to show that his glory days were behind him. It had been 20 years since Cortes had conquered the Aztec Empire and now everyone saw him simply as an aging conquistador to be indulged, but not granted any true authority.

Hernan Cortes died in Seville on December 2, 1547, aged 62. He left behind a mixed legacy, depending on who you ask. Unsurprisingly, Mexicans still regard him as a murderous villain who brought the plague of Western colonization to their lands, whereas for the Spanish, he remains an important figure who helped their empire reach the pinnacle of its power.