How do you measure the success of a pirate? Is it by fame? Is it by the number of ships they conquered, or the amount of treasure they pillaged? Surely, Henry Every deserves to be in contention for the title of “most successful pirate in history” because he was responsible for the single most profitable pirate raid in history – just one score netted Every and his crew around £600,000 in gold and jewels. The plunder was so large that it resulted in what many consider to be the first global manhunt in history as Henry Every became the most wanted man on the planet.

But then Every accomplished something almost unheard of in his line of work, something that almost no other famous pirate managed to do – he got away with it. Back then, pirates were fated to meet their end either at the bottom of Davy Jones’ Locker or at the end of a rope at the gallows. But Henry Every got his big score, took his share of the treasure and disappeared into the mists of time, never to be heard from again. This alone truly made him worthy of the sobriquet “The King of Pirates.”

Early Years

As is the case with other pirates, we find ourselves lacking a lot of credible sources on the early life of Henry Every. Sometimes he spelled his name Avery, but he also went by a few other monikers throughout his career such as Benjamin Bridgeman, Long Ben, and John Avery, which is believed to have been the name of his father.

He was born, most likely, in 1653 or 1659, depending on the source, near the English port city of Plymouth, in the county of Devon. His parents were probably John and Anne Every and some historians have speculated that they may have been connected to the prominent Every family which owned a lot of land in Devon and even had a branch that became baronets.

Henry Every took to the sea from a young age, serving on both merchant and Royal Navy ships. According to one account, Every was part of the English fleet that bombarded Algiers in 1671, he served as the captain of a logwood freighter in the Bay of Campeche in the Gulf of Mexico and also traveled to the Caribbean Sea for a while where he operated as a buccaneer. Unfortunately, all of these stories come from a contemporary book called The Life and Adventures of Capt. John Avery, published in 1709. It was written by Adrian van Broeck, the pseudonym of a man who claimed he was a captive of Every during his pirating days. Unfortunately, there is absolutely nothing to corroborate his tales and the book has been dismissed as almost certainly a work of fiction with the occasional truth included.

We get a better understanding of Every’s career after the breakout of the Nine Years’ War in 1688. It was fought between France, on one side, and pretty much all the other European powers on the other side, who formed a coalition known as the Grand Alliance. We first hear of Every when he was in his early 30s, serving as a midshipman aboard the 64-gun ship of the line HMS Rupert. Records also seemed to indicate that he already had a family at this point and that he sent them most of his wages.

In 1689, the HMS Rupert played an important role in capturing a French convoy off the coast of the port city of Brest. Following this success, most officers aboard the warship received promotions, including Every who became a Master’s mate, which is a title that doesn’t exist anymore. It is probable that the captain of the ship, Sir Francis Wheeler, took Every with him the following year when he was put in charge of a larger, deadlier, 90-gun ship called the HMS Albemarle. If this is true, then it is also likely that Every participated in the Battle of Beachy Head on July 10, 1690, which ended up being a crushing defeat for the English. It seems that he was discharged from the Royal Navy the following month.

Afterwards, it appears that Henry Every joined the slave trade for a few years, although this part of his life is also poorly documented so we don’t know what ships he served aboard and what ranks he held.

A Pirate’s Life for Me

In 1693, Henry Every joined a new venture called “Spanish Expedition Shipping.” At the time, the West Indies in the Caribbean Sea were split between the Spanish and the French who were still at war with each other. Spain was England’s ally so a group of wealthy London merchants formed this expedition which consisted of three frigates and a pink, the flagship being the Charles II, named after the King of Spain. Their mission was to travel to the Spanish West Indies to trade, salvage, supply the Spanish with guns and, most importantly, plunder all the French ships they met along the way. Basically, they were English privateers under a commission by the Spanish king.

Based on his record and experience, Henry Every was made first mate of the Charles II. This seemed like a pretty sweet gig at first, but it quickly went south as one bad thing happened after another. First, the original captain of the Charles II died while the ship was still in port. When the fleet finally left England, it headed for the Spanish city of A Coruña. However, thanks to delays and bad weather, the trip which was supposed to take two weeks lasted five months. When they finally found themselves in Spain, they had to sit in port for a few more months because the necessary paperwork had not arrived yet.

During all this time just waiting around, the men weren’t getting paid and they were becoming desperate. Upon joining the expedition, they had been given one month’s pay in advance and promised a guaranteed salary to be paid every six months. Once the ships were finally getting ready to leave for the West Indies, the crew demanded their six-months wages before heading out. Their request was denied and, unsurprisingly, this endeavor only had one possible outcome – mutiny.

According to reports from sailors who stayed behind, Henry Every was one of the driving forces behind the mutiny, going from ship to ship and talking to all the men to persuade them to join his side. On May 7, 1694, he and dozens of sailors stormed the Charles II and took the rest of its crew by surprise. Before the other ships realized what was happening and had time to react, he took the flagship into open water. Once they were far enough from Spain, the former captain and all the men who did not want to join were placed in a boat and allowed to go ashore. The only one who was forced to stay was the ship’s surgeon as his services were too valuable to forego. Henry Every was named the new captain and he rechristened his ship the Fancy.

To Madagascar

Now that Henry Every was a pirate, he had a ship, he had a crew, he needed one more thing – a destination. Where should they head to engage in their piratical ways? Back then, there was a popular sailing route, particularly used by English corsairs, dubbed simply the Pirate Round, which targeted the many merchant ships that traveled between North America or Western Europe and Southern Asia. It started from the Atlantic Ocean and rounded the southern tip of Africa, past the Cape of Good Hope, and with a stop on Madagascar. Back then, this island was a safe haven for pirates and a great place where crews could resupply and perform ship maintenance. From there, they could set various destinations which allowed them to prowl the Indian Ocean, looking for targets.

In fact, Every was one of the pirates who popularized this route since it was here that he took the biggest prize of his life, which we will talk about later. For now, we see him and his crew sailing off the coast of Africa. Whether or not Every committed any acts of piracy during this trip is yet another uncertain point. According to A General History of the Pyrates written in 1724 by the mysterious Captain Charles Johnson, Henry Every did not take any prizes until reaching Madagascar. There, he encountered two pirate sloops that quickly ran aground when they saw him as their crews scrambled to hide in the woods, believing that the frigate was still sailing under the British Crown and was there to take them down. Every sent unarmed messengers to talk to the pirates and even volunteered to join them himself in order to convince them that his ship was no longer flying the British flag. Eventually, once they were assured that he was telling the truth, the other pirates gleefully joined Every as now, with a frigate on their side, they could take down much more valuable prizes. As for Every, he had only been a pirate captain for a few weeks but was already building up a nice fleet for himself.

Again, all of this is according to Johnson and, as we already discussed in our Biographics video on Blackbeard (might want to check it out if you missed it), his identity is such a big question mark that we can’t even say with certainty that he was a real person. Pretty much everything he wrote comes under scrutiny but, unfortunately, he is also one of the main sources for many figures from the Golden Age of Piracy.

Other sources say that Every was far more active as a pirate right from the start. Allegedly, his first ever prize was, in fact, a triple – three English merchant ships that he captured at Maio, one of the islands that form the Cape Verde archipelago near the northwest coast of Africa. He continued on to Madagascar, but took several more prizes on the way, including two Dutch privateers and a French pirate ship which yielded dozens of men willing to join his crew.

The Biggest Heist in Pirate History

In 1695, Henry Every set his sights on a very ambitious target; perhaps the most ambitious, but also the most rewarding target sailing the Indian Ocean – the Grand Mughal Fleet.

During the 17th century, most of the Indian subcontinent, meaning most of India itself plus parts of Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh were part of the Mughal Empire. In Every’s time, this land was ruled by Emperor Aurangzeb.

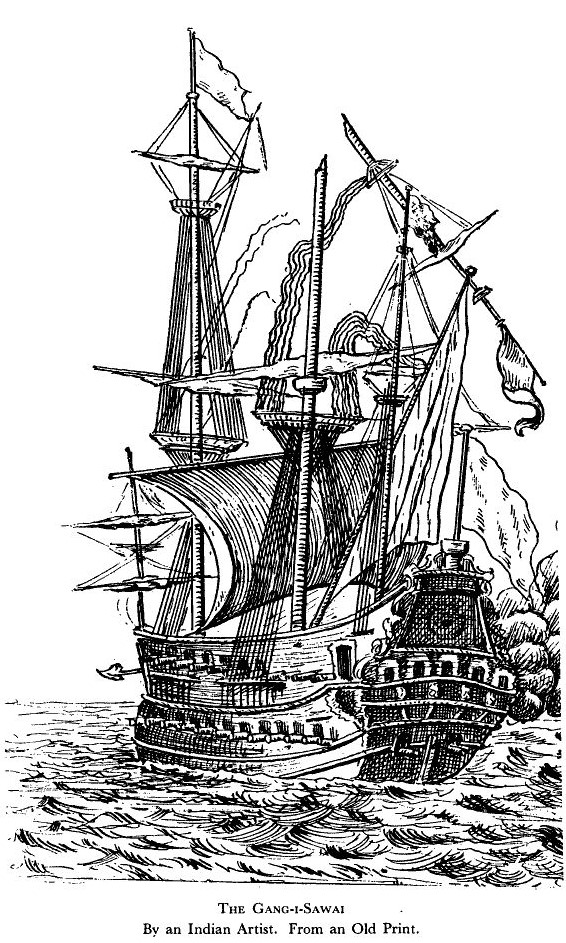

Every year, the empire formed a fleet to escort Muslim worshippers who went on the pilgrimage to Mecca called the Hajj. In 1695, that convoy consisted of 25 ships, but they were not carrying just pilgrims. They also included merchant ships that were filled to the brim with gold and other treasures. Among them, the biggest prize of the flotilla was the Ganj-i-Sawai, meaning “Exceeding Treasure,” but also anglicized as the Gunsway. It was a type of Indian trading ship called a Ghanjah dhow and, in September, it left the port city of Mocha and was returning to Surat in India.

How exactly Every knew of the dates when the fleet left port, we’re not sure. Maybe he got a tip, or maybe it was widely-available information since it was an annual pilgrimage. Either way, he realized that even just one of the merchant ships would make for the biggest prize of his life, but he could not do it alone. Not only were the merchant vessels armed, but they also had warship escorts since they were traveling in dangerous waters. No, Every needed help, and he got it from five other pirate captains who all wanted in on the action. They were Thomas Tew who sailed aboard the Amity, Thomas Wake who captained the Susanna, Joseph Faro on the Portsmouth Adventure, Richard Want on the Dolphin, and William Maze aboard the Pearl.

Realistically, apart from Every, only Thomas Tew was already a notable pirate in his own right. The others wanted him in charge of their flotilla, as the most experienced captain, but Every eventually won out, mainly because he had the biggest, most powerful ship.

In August, 1695, the pirates met at the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait that connects the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden and waited for the Grand Mughal fleet to pass through. It is actually unclear if Every and the other captains had met each other previously and agreed to convene here or if they all simply showed up at the same time, with the same intentions and decided that six ships were better than one. Either way, in September, the Mughal convoy passed through those waters and the pirates gave chase.

When the Mughal ships saw the pirates, they began dispersing. The Ganj-i-Sawai, as the biggest ship in the fleet, immediately fell behind, as did its escort, the smaller Fateh Muhammed. Even so, it became clear quite soon that some of the pirate ships were ill-fitted for this ambitious raid.

The Dolphin proved useless almost immediately as it was too slow to keep up with the rest of the ships. Eventually, most of the men abandoned ship and joined Every on the Fancy. Meanwhile, Thomas Tew and the Amity engaged in a fight with the Fateh Muhammed which had disastrous consequences for the pirates – Tew was killed by a cannon shot that, allegedly, pierced a giant hole through his stomach. Horrified, the rest of his men immediately surrendered and gave up the chase. Lastly, the Susanna also struggled to maintain the speed of the other vessels and was only present at certain points of the raid which lasted over a week.

The first ship that Every and the rest managed to catch up to was the Fateh Mohammed. Still damaged from its engagement with the Amity, the Mughal ship surrendered and it alone contained enough plunder to make the raid a success. Every, however, was determined to get his hands on the Ganj-i-Sawai.

A few days later, on September 7, he managed to catch up to the trading ship. At that point, only the Fancy, the Portsmouth Adventure, and the Pearl were still combat worthy. On the other side, the Mughal vessel was armed with dozens of cannons and 400 riflemen. The odds appeared to be in favor of the Mughal ship, but Every had no intention of backing down now. The same could not be said for Joseph Faro aboard the Portsmouth Adventure who decided not to engage.

Fortunately for Every, he also had luck on his side. During the fight, one of his first cannon volleys destroyed the Ganj-i-Sawai’s mainmast, leaving the vessel slow and vulnerable. More importantly, though, one of the Mughal ship’s cannons malfunctioned and exploded, killing its gunners, setting the deck on fire and causing a lot of panic and confusion. The pirates seized the opportunity and opened fire on all sides, afterwards successfully boarding the Ganj-i-Sawai and overpowering the crew.

From an Indian perspective, contemporary historian Khafi Khan blamed the defeat on the captain of the Ganj-i-Sawai, Muhammad Ibrahim. Besides his incompetence, he also acted cowardly, at one point allegedly running below decks, arming his slave girls and telling them to fight for him. Khan also reported that what followed was far more gruesome than the fight itself, as the pirates subjected the people aboard the Mughal ship to days of torture, rape, and murder, with many of them committing suicide by jumping overboard to escape the horrifying acts.

After days of barbarity, the pirates were ready to leave with their spoils. The exact value of the loot is difficult to estimate, but it was somewhere between £325,000 and £600,000, plus another £50,000 from the Fateh Muhammed. This would mean over $100 million in modern currency but, again, it’s just a rough estimate. The point is that one share represented more money than any sailor made in his lifetime and more than enough for them to retire.

But we do arrive here at another contentious point – sharing the spoils. Who got what? There were no participation trophies in piracy. Although six ships started out, only the two that actually fought the Ganj-i-Sawai were entitled to any of its riches. We have one account of what happened, again courtesy of Charles Johnson. He said that Every betrayed the other pirate ship and sailed away with the entire loot after convincing them that the safest place to store it was the cargo hold of the Fancy. Once that was done, he and his crew simply departed under the cover of night. According to other sources, there was a heated argument between the crews of the Fancy and the Pearl after the former accused the latter of trying to cheat them by clipping coins. As punishment, Every confiscated the treasure owed to the Pearl and, instead, only provided them with a modest sum to cover supplies and repairs.

Aftermath and Disappearance

Once news started to spread about the attack on the Ganj-i-Sawai, to say that it caused a commotion would be the understatement of the century. Emperor Aurangzeb flew into a rage once he learned about his treasure being stolen, but also about the defilement of the pilgrims returning from Mecca. He immediately placed the English in Surat under arrest and closed down factories which belonged to the East India Company with the intention of completely severing trade ties with England.

Eventually, there came a point in history when the East India Company became the largest private company in the world, and had a private army much larger than that of Great Britain, which it used to rule over India for a century. That point, however, was still 60 years away so, for now, they were at the mercy of the Mughal emperor. They promised to cover all the financial losses caused by the raid, and they placed a £500 bounty on Every’s head, later doubled to £1,000, which was unheard of for that time. It also came with a free pardon for any pirate who turned him in. To put it simply, Henry Every became the most wanted man on the planet.

The pirates might have successfully plundered the treasure, but getting away with it would be a whole new challenge entirely. First off, they needed to decide where they would sail next. Initially, they traveled to a French island near Madagascar named Bourbon which was a safe haven for pirates. That is where they divvied up the loot and planned their next step. Some of the men stayed behind on Bourbon. Others left the crew and secured passage on different ships on their own. As for Henry Every and the rest of the pirates aboard the Fancy, they decided that the Bahamas would be the safest place for them.

In March, 1696, the Fancy arrived at New Providence, the island that contains the Bahamian capital of Nassau. There, Every adopted the name of Henry Bridgeman and convinced the Governor, Sir Nicholas Trott, that they were unlicensed slavers hiding from the East India Company. Accompanied by a generous bribe, the story was enough to secure the pirates safe haven in Nassau. It probably didn’t hurt that Every’s ship was the most powerful vessel for hundreds of miles so the governor had the choice of either making a friend or an enemy out of him.

Even so, when you are the target of the largest manhunt in the world, your cover will not last forever, especially when your wealth mostly consists of diamonds and foreign gold coins. When Every’s true identity was discovered, Trott had no other choice but to issue an arrest warrant for him to avoid making himself complicit in his escape. Even so, the governor clearly was not a friend of the East India Company or the British government, as he tipped off Every that ships were on their way to arrest him. The captain and most of his crew had time to escape, with only a few men staying behind and getting captured.

It seemed inevitable that everywhere Henry Every went, someone would discover his true identity. And yet, he seemingly did the impossible – Henry Every vanished. Nobody knows what ultimately happened to him, his crew, his ship, or his treasure.

Everything from this point on is pure hearsay and rumors. Allegedly, they tried going to Jamaica, but the same thing happened as in Nassau. From there, the crew split into groups – some stayed behind in the Caribbean, most traveled to North America, and the last group which included Every himself returned to England under assumed names.

The most complete account is given by Charles Johnson again. He said that Henry Every first traveled to Boston, intending to settle in the New World, but changed his mind and later sailed to Ireland. From there, he needed to find a way of selling his ill-gotten gains without being discovered. He made an arrangement with some merchants from Bristol, but they ripped him off and stole most of his share of the treasure. Every couldn’t do anything against them as they threatened to expose his true identity, so he retired almost penniless to a town in Devon County called Bideford.

This version of the story is so much more detailed than all the other accounts that, unless Charles Johnson personally met Henry Every at some point, it is almost certainly a complete fabrication. The reality is that we will probably never truly know what the ultimate fate was of the King of Pirates.