During the American Civil War, the country was embroiled in so much fighting that it’s astounding the country still exists today. No fight was more profound than the struggle for black slaves to finally earn their freedom. After all, the staunch belief from the American South that they had a right to own slaves was a primary force in the war beginning in the first place. But even decades before the war highlighted the need for America to end slavery, many people were finding ways to get slaves to freedom. Harriet Tubman went above and beyond. But that’s just one part of her rich story.

Childhood

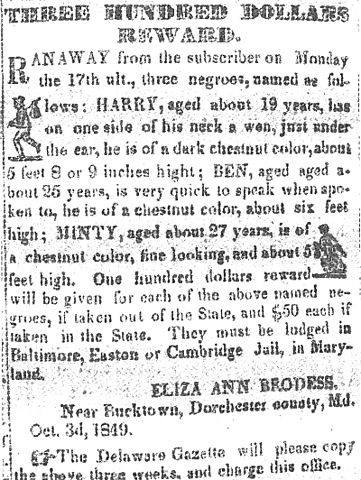

Harriet Tubman was born in the month of March 1822, in Dorchester County, Maryland. Her birth name was Araminta Ross, and she was affectionately known as “Minty” during her childhood. She was also born into slavery, as her parents, Harriet and Ben, worked a plantation near the Blackwater River in Dorchester. Obviously, records are hard to come by regarding Harriet’s birth, but historians have reached the year of 1822 as probable based on documents from the time, though her gravestone says 1820 and she herself said it was 1825.

We also don’t know a lot about her family, other than the fact that her grandmother arrived in American on a slave ship. Her parents held important positions on the plantation, as her mother was a cook for Mary Brodess, who oversaw the plantation. Her father looked over all the timber production. The couple had nine children, including Harriet, but found it harder and harder to keep the family together as slavery’s massive reach encroached. Three of their daughters were sold off, losing touch from the family forever, but when they came to sell off one of their sons, Harriet’s mother boldly stood up and refused Mary Brodess. Shockingly, Brodess relented, and the sale was canceled. Harriet saw this defiance, and was surely inspired by it.

Harriet eventually was given work as a nursemaid when she was five or six, while also helping to raise some of her siblings. She also worked for a local planter named James Cook, and she would often work his property, checking muskrat traps throughout the marshes that dotted his land. They worked her hard, even when she got measles and had to be cared for by her already-busy mother.

Her nursemaid task back at the plantation was much harder than she could have anticipated, as regular whippings would occur even for simple things like a baby crying. Harriet already was developing clever ways to avoid the pain and the beatings, like wearing extra layers of clothing, and just plain running away for days on end.

Harriet’s Growing Pains

With time, Tubman was given more arduous tasks like plowing and hauling logs. She was easing into her teenage years, and even though her home was one of the most horrible places you could imagine, it was still all she had, and she tried to find the little peace that she could. . Tubman was unable to read, but knew the Bible and its teachings quite well from her mother. That religious strength was soon to be tested, as she suffered a nasty injury on the plantation around this adolescent time.

As another slave was attempting to escape, one of the plantation supervisors threw a metal weight at them, which instead struck Harriet in the head. The injury was profound: it not only led to her suffering seizures and excruciating headaches, but it led to a period of her having what she said were visions. She began to reject the ideas in the New Testament of the Bible, and instead pursued tales of revolution and freedom. Whether the injury caused this change in her mind is unknown, but the symptoms remained with her to her dying day, and recent historians think she might have had a form of epilepsy after the attack.

Credit: Daniel L. Brandewie – 自己的作品, CC BY-SA 4.0

Harriet reached her first roadblock to freedom early. There was a practice back then called manumit, which is an agreement where an owner formally frees a slave. Oftentimes, this came about when a slave reached an age where the owners felt they had gotten all the possible use out of them, physically and mentally. Harriet’s parents were supposed to be granted manumit at the age of 45, but their owners all but ignored that when they took over. So besides her parents being denied some small semblance of freedom, Harriet too would remain in slavery.

She did marry a free black man named John Tubman in 1844, and that wasn’t so strange around those parts of Maryland back then. Maryland always straddled the line, and so roughly half the black population in those regions were free. That didn’t matter to the law much, as Harriet would still remain a slave regardless of her marriage status. She did choose her true name soon after. No longer was she Araminta Ross. She was now Harriet Tubman.

Her health was still an issue, however, and whether that was directly from the head injuries and subsequent symptoms is unclear. Her owners were beginning to consider her a liability, and not having the value she once had as a worker. In 1849, they tried to sell Harriet off, and found no takers. Tubman remained humble, escaping from her real-world horrors into the peace of prayer, even asking forgiveness for her owners. That line of prayer eventually changed to asking for the lord to take him, which actually happened a week later.

The death of her owner instantly put her life in immediate disarray. Where would she end up? What would become of her family? The thought of spending another day as the property of someone else made Harriet decide that breaking free was the only option.

Breaking Out

On September 17, 1849, Harriet and two of her brothers made their great escape. Their absence went unnoticed for two weeks, which should have bought them a nice cushion of time. But the news then got announced in the local papers, and her two brothers became fearful, eventually returning to the plantation. Harriet, ever the faithful family member, joined them. But this was just the trial run for Harriet. She was getting out.

Not long after, Harriet busted out again, this time without her brothers in tow. She wanted to make sure her family knew that she was planning this, and sent them coded messages through song. She traveled by night, with the stars as her guide and utilizing the Underground Railroad, which was a loose network of activists and former slaves. While little is known about which direction she took, it’s likely she followed the nearby Choptank River, then went north through Delaware and Pennsylvania, eventually ending up in Philadelphia.

The Underground Railroad was her ticket to avoid capture. Rewards for fugitive slaves were plentiful, but so too were people who were eager to be on the right side of history. The Railroad, while not actually any kind of transit system, was a series of routes and safe houses which extended as far north as Canada, and as far south as Mexico. Its origins go as far back as the late 1700s, and by the time the Civil War began, it’s estimated that over 100,000 slaves found their freedom through the Underground Railroad. The North Star, which Harriet followed to her Philadelphia, became a kind of crucial mapping point, leading the way north to free states. There was even a spiritual song at the time called “Follow the Drinking Gourd”, which was referencing the Big Dipper constellation in code and basically giving directions for slaves to find their freedom.

Harriet used these same clues and markers to find the way, but her journey wasn’t without peril. She had to hide by day, and then use the cover of night to find the next friendly location. Some people at her stops had her pretend to work for the family so as not to blow her cover. When she finally crossed into Pennsylvania after a 90 mile, several week trek on foot, she said:

“When I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over everything; the sun came like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven.”

The Rescue Missions

Tubman was free, for now. But her family wasn’t. Neither were the over 3 million other slaves in the United States. Congress in 1850 tightened penalties on aiding slaves in escaping and forced authorities to help capture them, even if it was in a free state. Even in the relative safety of Philadelphia where Harriet was, poor Irish immigrants and blacks were embroiled in racial tensions over jobs and work. Harriet was able to find some odd jobs here and there and save a little bit of money, while she thought up ways to get her people their own tastes of freedom.

She didn’t have to wait long. In December 1850, word reached that her niece Kessiah and two children were about to be put up for sale back in Cambridge, Maryland. Tubman headed to Baltimore and laid low with a family member until the sale date. John Bowley was Kessiah’s husband, and as a free black man, he was able to put up the winning bid for her. When the man running the auction went off to have lunch, Bowley snuck Kessiah and the children to a safe house until nightfall. He then loaded them all onto a canoe and sailed 60 miles up to Baltimore, where Harriet was waiting to take them to Philadelphia. Her first successful rescue, and far from the last.

In spring 1851, she headed to Maryland again to rescue her brother Moses. She was becoming more and more confident in her travels, and word was beginning to spread around the region and to her family of her exploits. In fall of that year, she actually returned to her home county of Dorchester, this time to attempt to rescue her husband, John Tubman. Unbeknownst to her, John had remarried. Still, she tried to persuade him to follow her to safer parts. John was adamant that he was happy with his new life and wife, and thought Harriet was upset, she decided it was best to leave him behind. She instead found some slaves in the neighboring area who did want to escape, and took them back to Philadelphia with her. In December, she escorted 11 more.

Those eleven slaves she rescued are of special note, because it’s very likely she led them to freedom after they were under the care of Frederick Douglass. He stated in his autobiography that he was looking after eleven slaves at his home, and the timing of her leading that number of fugitives seems to match up perfectly. Douglass and Tubman already had a great respect for each other, as he was a former slave before becoming the prominent abolitionist you know today. He eventually wrote a very poignant letter in her honor, remarking how he very publicly denounced slavery, while she fought it privately.

Harriet Tubman led thirteen voyages back to Maryland in all, rescuing some 70 slaves and leading them north to safety. She saved even more of her family, her brothers, their wives and children. She counselled with many other slaves, directing them before they embarked on their own perilous trips to freedom. She mostly worked during the winter, as those climates seemed to offer the least chances of being caught. She and her passengers usually took off on Saturday nights, as runaway notices wouldn’t be live in the newspapers until Monday morning. Harriet devised all sorts of tricks and tactics to avoid detection. Sometimes she would carry angry chickens so she wouldn’t have to make eye contact with plantation owners. Even though she was illiterate, she would feign reading newspapers so passersby wouldn’t catch on to her mission.

She also carried a gun with her. This wasn’t just for protection against people who would love to have caught her and gotten their reward – it was also to make sure no one she was rescuing would have second thoughts about being rescued. After all, if someone had tried to back out, that would have put the safety of the group as a whole in jeopardy.

It was known around those regions of Maryland that someone was helping a good number of slaves escape. They never got wise to it being Tubman. They figured she had escaped, and gotten to a better place, and had no reason to return. Many thought white abolitionists were behind all the escapes. But for all of her daring expeditions into the belly of the beast, including where she herself had toiled in slavery, she was never once caught.

One of her very last trips was to steal into Maryland and rescue her parents. In 1855, her father had purchased the rights to her mother, and both lived as free blacks, but the area still wasn’t the kindest place for them to reside. In 1857, her father got in trouble for being found protecting eight slaves in his home. Harriet saw the danger he was facing, and headed down to Maryland for one last mission. She picked her parents up, led them all the way to Ontario, Canada, and got them situated on a piece of land that also included her brothers and many other former slaves. Harriet found a way to reunite much of her family, after being separated by so many forces for so long.

Joining Forces

Harriet Tubman crossed paths with another famous anti-slavery force in 1858 when she was introduced to John Brown, an abolitionist who advocated for armed revolt against slavery. You may remember his name being attached to the famous raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859. He and his group seized a federal armory there with the intention of arming slaves. While the raid was at first successful, it didn’t last long, and Brown and his men were captured. John Brown was actually the first person convicted of treason in U.S. history, and he was hanged.

Brown and Tubman were fast friends, even if Tubman didn’t believe in his more violent methods. Brown endearingly called her “General Tubman”, and he used her vast knowledge of the Underground Railroad and similar networks to plan his own maneuvers. He also had Tubman reach out to the former slaves she had helped relocate to Canada, to request their help in fighting for his cause. On May 8, 1858, Brown met with Tubman’s people, and proceeded to unveil his plan for the Harpers Ferry raid. His plans were almost immediately put on hold when the government got wind of them, but he still worked on them behind the scenes, often with Harriet Tubman’s help.

But when it was time for the raid to take place, Tubman was unavailable for Brown to lean on for guidance. He forged ahead anyway, and while it was an eventual failure, he had already won the praise of Tubman and many other leaders of the anti-slavery cause. Harriet herself said:

“[H]e done more in dying, than 100 men would in living.”

In 1859, Harriet joined up with another abolitionist, this time Republican senator William Seward, and she was able to purchase a plot of land in New York state. It cost her $1200, and the town where it was located was perfect for Harriet. It enabled her to get her family members away from the sometimes-brutal Canadian climates, and the nearby city of Auburn was very anti-slavery. Harriet still went down south from time to time to conduct rescue missions, and oftentimes she would bring them right to her New York property, creating a safe haven of sorts for all kinds of former slaves.

Harriet and the Civil War

1861 saw the Civil War break out. It was inevitable; the push and pull inside the country regarding slavery and its moral implications was bound to explode at some point or another. And when it boiled over, Harriet believed in the cause of the Union and its anti-slavery stance. She wanted to help, and so she joined a group of abolitionists from Boston and Philadelphia, as they headed down to South Carolina, where the Civil War began. She assisted in the camps there, helping to care for escaped and recently-freed slaves. She even began assembling a regimen of soldiers consisting of former slaves, under the tutelage of General David Hunter.

One person who wasn’t pleased with the work Harriet and General Hunter were doing was President Abraham Lincoln. He didn’t think it was time yet to force the southern states to free their slaves, and he actually came down pretty hard on them for their actions. Tubman of course wasn’t one to mince her words, and she retorted back against Lincoln for what she saw as weakness:

“God won’t let master Lincoln beat the South till he does the right thing. Master Lincoln, he’s a great man, and I am a poor negro; but the negro can tell master Lincoln how to save the money and the young men. He can do it by setting the negro free. That’s what master Lincoln ought to know.”

Still, Tubman helped where she could. She worked out of Port Royal, South Carolina mostly, helping scores of soldiers suffering from smallpox and dysentery. She made her own pies and root beer to earn some money, denying the rations that the government attempted to give her for her work.

It took two years until Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was issued, the first step in ending slavery. Harriet was still working out of South Carolina, and the landscape was much like where she grew up in Maryland, so she led bands of scouts around the swamps and rivers in the area, gaining reconnaissance and intel on the enemy Confederate forces. She worked under direct supervision of the Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, and then later aided General James Montgomery with information that helped him take the city of Jacksonville, Florida.

Harriet was often pulling strings behind the battlefields, but that didn’t mean she didn’t take part in some of the action as well. Tubman became the first woman to lead a battlefield operation, when General Montgomery decided to sack a series of plantations along a South Carolina river. Tubman advised him and helped to lead the raid. She guided boats of soldiers around enemy mines in the waters. She watched as Union men stormed the shore and burned down plantations. The slaves interned there realized this was a liberation, and fled towards the waiting boats on the shore, carrying what food and possessions they could as the plantation owners tried to stop the mass exodus. Harriet beamed with pride at what she helped happen there that day. Over 750 slaves were freed during these missions. Harriet was rightly lauded as a hero, and many of the people she helped escape their captors went on to join the Union Army to fight.

Harriet Tubman helped the Union for two more years, caring for wounded soldiers, scouting enemy territory, and helping freed slaves adjust to their new lives. She did all of this while also traveling back to New York to see to her family and those living at her sanctuary. Once the war ended in 1865, she went back there for good.

Harriet, After the War

Harriet spent her older years caring for her family and parents, and taking in boarders to help earn a little money. One of them was a man named Nelson Charles Davis, whom she quickly took to, though he was 22 years her junior. They married in 1869, and adopted a little baby girl named Gertie five years later.

Tubman’s old abolition comrades never forgot her even as the years rolled on. One even penned a biography of her, which Harriet saw some royalties from. She still didn’t receive the recognition she deserved from her past deeds, which was proven time and time again. A bill that was proposed in Congress to pay her for her service with the Union Army was defeated in 1874. She was swindled out of money by con men, and assaulted during a train ride, even though she had government papers proving she could sit in the section she was in.

Still she fought. She traveled up and down the east coast in the 1890s to fight for womens’ right to vote. She also turned more toward her spiritual side. In 1903, she donated a sizable piece of land of hers to the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, with the stipulation that it would be a home for “aged and indigent colored people”. Frustrations mounted as it took years to complete the facility, and once it did open, charged one hundred dollars as an entrance fee. Still, she was happy to put her name on the Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged.

It would be one of her last cherished memories. The seizures and head problems she’d dealt with her entire life were more numerous. She underwent brain surgery in Boston somewhere around this time, having her skull opened up with no anaesthesia, biting down on a bullet like she’d seen mortally wounded soldiers do in the past. Tough to the end. In 1913, she passed from pneumonia in her namesake home for the elderly. Her last words were “I go to prepare a place for you.” She was buried with some military honors in the town of Auburn, New York, where she had created her haven for those who were once enslaved, after guiding so many on the Underground Railroad to freedom.