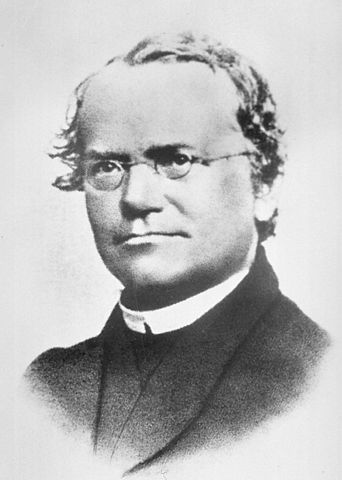

In February, 1865, an Augustinian friar stood up before a small crowd in the Moravian city of Brno, and delivered a lecture that changed the course of history. For the last 8 years, Gregor Mendel had been cultivating peas in his abbey’s garden. Each plant had been carefully selected for its characteristics – like tall or short, or yellow or green – and then painstakingly crossbred to create generations of hybrids. The result was not just a shedload of peas, but a whole new science. It was from Mendel’s notes that the entire concept of genetics sprang, a branch of biology that would fundamentally change our understanding of the world. But here’s the kicker: no-one would realize what a breakthrough Mendel had made for another 35 years.

At the time he delivered his lecture, Gregor Mendel was middle-aged, anonymous, and virtually unknown outside of Brno. In his lifetime, he’d traveled little, experienced less, and mostly just lived in his abbey. Yet, somehow, this nobody single-handedly made one of the greatest discoveries in history. Today Biographics is delving into the life and mind of Gregor Mendel, and discovering how this one monk transformed our world.

The Boy from Nowhere

Of all the branches of science, genetics may be unique in that it can be traced back to a single person. But if your vision of a man so brainy he can uncover whole new sciences is some wild-haired Rick-style genius, lording it over the simpletons around him, prepare to be disappointed.

Gregor Mendel wasn’t just a modest man, he came from a background so modest he nearly didn’t study science at all. Born Johann Mendel on July 22, 1822, young Mendel was the son of farming parents eking out a living in the Silesian foothills in modern-day Czech Republic.

At that time, Silesia was part of the Austrian Empire, one of the great powers of Europe, and Mendel grew up speaking German.

But since nearly every location in our story has long since lost its German name, we’re just gonna use the modern, Czech names when referring to places. That way, if you wanna look stuff up after, you’ll actually be able to find it.

For Mendel and his parents, life in remote Silesia wasn’t exactly easy.

The family was always teetering on the edge of financial catastrophe, and ma and pa Mendel harbored no great dreams for their son beyond having him grow up and help run the farm.

That may very well have been Mendel’s fate, had it not been for one man.

When Mendel was aged 11, the village priest – who also doubled as the local schoolmaster – came to the family farm asking for a meeting. There, he told Mr and Mrs Mendel that their son was exceptionally bright. Astoundingly so.

In fact, the schoolmaster said Mendel was so clever that he should be allowed to continue his education.

Now, this wouldn’t exactly have been music to the family’s ears.

In the Austrian Empire, sending a child off for secondary education often involved paying fees that most families simply couldn’t manage. While Mendel’s parents weren’t dirt poor, they also couldn’t afford to spend crazy money on something as nebulous as learning.

But the schoolmaster insisted. And, eventually, the family caved.

So it was in 1834 that Mendel left his village for the first time to go and study in Opava. For the gifted country boy, life in industrial Opava wasn’t what you’d call enjoyable. In a real city for the first time, Mendel failed to fit in, or adapt to the pressures he felt to succeed.

He frequently fell ill, plunging into deep, dark depressions that would keep him from studying for days. It was the first flicker of the disease that would come to haunt Mendel for his entire life. But those black days were still in the future. Despite the strain at school, Mendel graduated in 1840 having excelled in his studies.

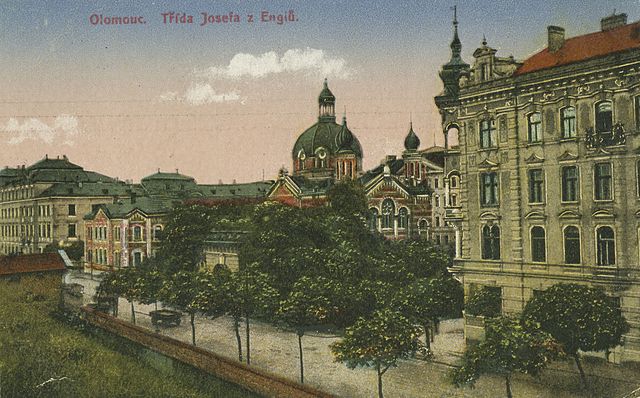

In fact, he did so well that his parents allowed him to continue on to university in Olomouc. A small, beautiful city amid the rolling hills of Moravia, Olomouc is less than 70km from Opava, but must’ve felt a world away.

Gone was the industrial detritus of Silesia, replaced by clear air and baroque majesty.

But even such Instagram-ready surroundings couldn’t stave off Mendel’s black thoughts. While at Olomouc, Mendel’s mental health came close to total collapse. Twice he had depressive episodes so deep that he dropped out his math studies, sloping back to his disappointed parents.

Both times, though, he eventually recovered enough to return to Olomouc. But even then money worries left him badly overworked, forced to tutor alongside his studies to make enough to eat.

But he made it through. In 1843, Mendel graduated.

His parents must’ve breathed a sigh of relief. Finally, their son was coming home! But home was the last thing on Mendel’s mind.

Depressed as he’d been at Olomouc, he still wanted to study. He just needed a way to do so without any financial pressure suffocating him. Luckily, in the Austrian Empire of the mid-19th Century, such a way existed.

Brno Days

One of the strangest things about Mendel’s life story is just how much of it was made possible by other people. At every important moment, there was someone there to push him in the right direction. Someone like the village schoolmaster.

Someone, too, like Abbot Cyril František Napp.

An Augustinian, Napp deeply believed in the creed dictum per scientiam ad sapientiam (from knowledge to wisdom).

As head of the abby in the great industrial city of Brno, some 60km from Olomouc, he’d devoted his life to building a center for study. He supported his monks in scientific endeavours, helped them get university placements without paying fees.

For Mendel, this was exactly what he needed. In 1843, he joined the order, taking the name Gregor. For the rest of his life, Mendel would be based in Napp’s abbey in Brno.

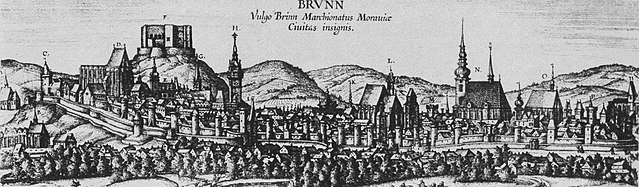

Speaking of Brno, it’s time we got to know the place Mendel called home.

The Czech Republic’s second city, Brno today has a reputation for being pleasantly boring, the sort of place where life is a steady procession of Sunday afternoons. Back in the mid-19th Century, though, it was an industrial powerhouse; a multicultural center where vast German, Czech, and Jewish communities rubbed shoulders.

From this melting pot would spring minds as great as Ernst Mach and Kurt Gödel, or musical talents as great as Leoš Janáček – someone else whose talent was spotted by Abbot Napp. In short, this was the exact right place, at the exact right time if you wanted to change the world.

Not that Mendel had any inkling of his destiny just yet.

In fact, his first years at the abbey seemed almost a mistake. Part of Mendel’s duties after being ordained was to visit the sick and the dying of Brno, to offer them comfort. But country boy Mendel found the booming city so overwhelming, and the lives of the poor there so sad and squalid, that he started to crack apart.

In 1849, he had another breakdown, this one plunging him so deep into the black ocean at the bottom of his mind that it took nearly a year to recover from.

Thankfully, Abbot Napp was super-enlightened where mental health was concerned.

He gave Mendel space and support to recover, then quietly assigned him to a much-less taxing job teaching in the much-less frantic nearby town of Znojmo.

For Mendel, this seemed the perfect combination. He didn’t just recover in Znojmo, he flourished.

Sadly, though, it wasn’t meant to last.

In 1850, the Austrian Empire suddenly shook up its education system. Teachers could no longer teach just because they were clever and needed work, they now needed a qualification to set foot in a classroom.

You can probably guess what happened next.

The strain of the exam caused Mendel’s nerves to come back, leaving him unable to continue teaching. At this point, it must’ve looked like the young man was destined for nothing more than a life of battling his illness, with only the occasional ray of sunshine breaking in to keep him going.

But Abbot Napp thought differently.

The following year, 1851, he encouraged Mendel to enroll at the University of Vienna, which was just opening brand new courses on science. It seems the abbot hoped to give Mendel something to focus on, to distract him from his problems.

Instead, he wound up handing Mendel the keys to his future.

The Monk in the Garden

If Gregor Mendel thought Opava and Brno were big, we can’t imagine how he must’ve felt when he first saw Vienna. The capital of an empire that stretched all the way from the Alps to the Carpathians, 19th century Vienna was one of Europe’s great cities.

Under the new emperor, Franz Josef, it would soon grow to become a cultural and artistic powerhouse. But if Mendel found the sprawling, multiethnic city overwhelming, he never showed it.

His two years studying in the capital passed calmly, without a hint of the mental strain that had accompanied such moves before. Maybe the difference this time was that Mendel was able to get fully involved in his courses, rather than worrying about how to make money to pay for them.

And what courses they were. Mendel studied experimental physics under Christian Doppler (of Doppler Effect fame), and practical biology under Franz Unger. Although forgotten today, Unger was a leading light of Austrian biology in the 1850s, and its closest equivalent to Richard Dawkins.

Unger was a huge proponent of the pre-Darwinian evolutionary theory of hybridization, which rejected Church doctrine in favor of a natural – if incorrect – theory for how animals evolved.

Naturally, this made him a huge hate figure among the devout, and Unger spent the entire period he tutored Mendel fending off attacks in the popular press. Yet, for all the flack Unger caught from the hardcore religious, he doesn’t seem to have repulsed the monk Mendel at all.

In fact, he appears to have inspired him.

The year after he graduated and returned to Brno, 1854, Mendel approached Abbot Napp with a plan. He wanted to run a hybridization experiment at the abbey, likely the biggest the world had ever seen. At the time, there was a huge disconnect between what was theorized about hybrids, and what practical experience told you.

The orthodoxy was that an animal was an animal and it didn’t change, no matter what. So, if you had – say – a labrador and a poodle, they might produce one hybrid offspring, but future generations would revert back to being separate species.

But that didn’t tally with the lived experience of animal breeders, who were all like “dude, just look at all these labradoodles. Where do you think they came from?”.

What was needed was someone with the time, patience, and mathematical training to investigate this problem across thousands of specimens and multiple generations to figure out what was going on.

Someone like Gregor Mendel.

Initially, Mendel wanted to run his gigantic experiment on mice. But, perhaps realizing that “experimental genetic research” and “things with teeth” sounds like the set-up for a terrible horror movie, Abbot Napp refused.

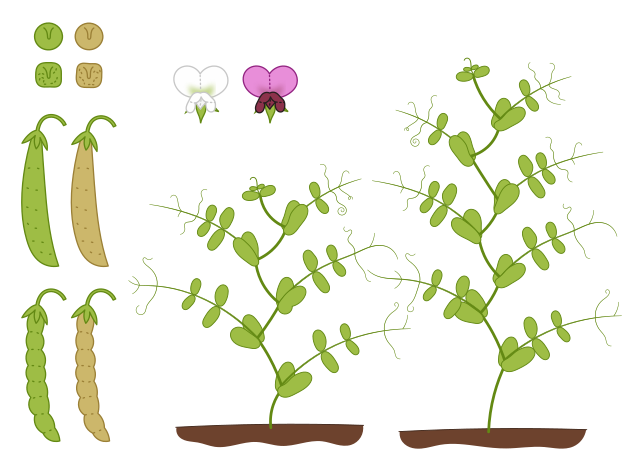

Which is how Mendel came to settle on the thing we all know him for: peas. Starting in 1856, Gregor Mendel spent eight years breeding different types of peas and meticulously recording the results.

By one count, he bred and analyzed over 30,000 separate plants. If that sounds like an extremely boring way to spend the best part of a decade, well, no arguments there.

But the effect it had would be anything but dull.

In a short time, this one monk working in his garden was going to overhaul everything biologists thought they knew.

The Founding of Genetics

If you’re wondering now why nobody had bothered to do this research before, you’re not the only one. Mendel himself seemed flabbergasted by the lack of scientific interest, writing that:

“No one has concentrated on the number of different forms that appear among the offspring of hybrids. No one has arranged these forms into their separate generations. No one has counted them.”

But there may have been a good reason for that. The work Mendel undertook was almost painfully tedious. The first stage was for Mendel to select varieties of peas to cultivate. He wound up choosing seven types, with binary characteristics that were easy to detect. For example: tall or short, yellow or green, and so on.

This was important, because people looking into hybrids pre Mendel had been like “OK, these are all way different. Let’s crossbreed them and see what happens.”

But Mendel’s scientific training made him more rigorous. He only wanted to crossbreed those with opposing characteristics, at least at first. So that meant making sure the tall plants bred with the short ones, the yellow ones with the green ones.

It must’ve been insanely fiddly work. The sort of work that would make most people question their choices in life. Yet Mendel kept it up. He kept it up across eight whole years, across uncountable generations of pea hybrids.

Slowly, patterns began to emerge.

Credit: Nefronus – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

Let’s take flower color as an example. One of the varieties Mendel worked with was pea plants that flowered either white or purple. Mendel noticed that when he crossbred them, the next generation of plants all had purple flowers. It was almost like the whites had never existed.

But when Mendel took those hybrids and kept right on breeding them, something interesting happened.

In the subsequent generation, white flowers reappeared. Not many, but roughly around 25% of the new generation of hybrids. It was from this observation that Mendel’s greatest work was born. We don’t want to get too far into the weeds with this – we’re a history channel, not a science channel – but we’ll give you the bare bones version of Mendel’s conclusions.

The first was that certain traits are what he called “dominant”, like the purple flowers in our example, while others are “recessive”, like the white flowers. These traits were passed down at random from parent to child.

The second was that these traits were all passed down independently of other traits. So, just because a ‘white flower’ trait was passed down didn’t mean a ‘tall plant’ trait necessarily came with it, or whatever. Mendel’s third and final insight was that you could graft a basic statistical framework onto this to predict what traits might show up across a population.

It was from these key conclusions that the entire idea of genetics would eventually be born.

Not that Mendel realized this.

Although he theorized his findings could be applied to any living thing, he seems to have repeatedly missed the implications. In 1862, for example, he read Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, without ever twigging that their work could be combined to explain so, so much about existence.

Yet Mendel wasn’t so unworldly that he just kept his findings for the abbey. He still wanted to tell people about his work.

It’s just a shame that, when the time came, no-one would be listening.

First they Ignore You…

In 1861, Gregor Mendel had co-founded the Natural Science Society in Brno.

Conceived as a place to discuss new ideas, as well as an outlet for any work its like minded members did, the society soon became a key part of Brno’s intellectual life. It also gave Mendel a useful place for revealing his breakthrough.

That revelation came on February 8, 1865.

That cold evening, the Society converged on a building in central Brno. There, as the freezing members huddled around the stove, Mendel gave the first of two presentations on his findings. The title was Experiments in Plant Hybrids, and it ran to a mere 47 pages written down. It wasn’t designed to be ostentatious.

But it was revolutionary.

It seems those attending knew it, too. Mendel’s two lectures became the talk of Brno’s scientific circles. Yet for some strange reason, word never spread beyond the Moravian capital. It wasn’t for lack of trying. The Society published Mendel’s lectures as a book in 1866, and sent reprints to libraries across the empire.

They even sent a translated version to Charles Darwin in England. But Darwin simply did what everybody did with Mendel’s book. He put it to one side…

…and forgot all about it.

The trouble was, it just appeared so boring. Oh great, a book on breeding peas. Um… thanks? Even those that did read Mendel’s work often came away thinking it was applicable only to the vegetable garden. So interesting, but only if you were a horticulturalist.

It didn’t help that Mendel refused to promote his own work, seemingly resigning himself to not being understood. He told a colleague in 1866: “I knew that the results I obtained were not easily compatible with our contemporary scientific knowledge.”

But perhaps the biggest reason Mendel’s work fell into obscurity was loss.

In summer, 1867 Abbot Cyril Napp passed away, aged 74. It was a blow not just to the abbey itself, but to Brno as a whole. With one of the great intellectual lights of the city gone, the friars looked desperately for a replacement, someone who could take over from Napp.

They found their man in Gregor Mendel.

In 1868, Mendel became abbot of Napp’s old abbey.

It was a great promotion, the sort of life the poor farm boy from Silesia could never have dreamed of leading as a younger man. Unfortunately, it was also a life crammed with responsibilities. With no free time left, Mendel abandoned all his scientific pursuits. His peas were forgotten, his lectures discarded from his mind.

And that was it for the rest of his story.

It feels cruel, to skip over a whole sixteen years of a man’s life like that. But, really, there’s nothing more for us to say.

From the moment he became abbot, Mendel did nothing of note. He got older, his eyesight failed, he contracted Bright’s Disease and lived in some pain, and he spent his last years fighting the Austro-Hungarian state over new taxes levied on monasteries.

When he finally died, on January 6, 1884, he was remembered not as a scientist, but as a familiar face around Brno. Nothing more, nothing less. If people had been taking bets on his name being remembered in over 130 years’ time, you would’ve got fantastic odds.

But sometimes, just sometimes, a long shot comes in.

It would take decades more, but Mendel would eventually become world famous.

Rediscovery

Curiously, the one person who seems to have been certain Mendel’s name would live on was Mendel himself.

Before he died, he wrote to a friend:

“My scientific studies have afforded me great gratification; and I am convinced that it will not be long before the whole world acknowledges the results of my work.”

He soon turned out to be more right than even he could’ve guessed. The rediscovery of Mendel, and the start of his influence on the world, came about in 1900. That year, three separate scientists all separately published work on hybrids that was suspiciously similar to Mendel’s.

We say “suspiciously” because even today, no-one’s quite sure what happened.

The official story is that Hugo de Vries, Carl Erich Correns, and Erich Tschermak von Seysenegg all declared they’d made a breakthrough, only to be astonished when proof was found that Mendel had done the same decades earlier.

However, there’s evidence each of these men may have read Mendel’s book prior to their research, and may have independently decided it was exactly obscure enough to steal from without being noticed. Regardless of how it happened, though, their papers made the scientific community turn back to Mendel’s work for the first time in 34 years.

What they found there blew their minds.

It was clear to people living in the 20th Century that Mendel had hit on something big. One of his new acolytes, William Bateson, even coined a name for what Mendel had studied: “genetics”. In no time at all, Mendel was all the rage. While the serious scientific community turned its nose up at the new science for several years, more breakthroughs soon made the field respectable.

With that, Mendel’s legacy was secured.

Today, Gregor Mendel is remembered as the father of genetics, the man from whose work everything in the discipline springs. Incredible as Mendel’s work is, though, what’s more incredible may be that it happened at all. Looking back across his life story, we can see that Mendel was one of those people history seems destined to completely pass by.

His life was so sheltered, so anonymous that even the biggest events of the day barely touched upon him.

I mean, this guy lived through the 1848 revolutions. We’ve done enough 19th Century videos by now to know that anyone who lived through 1848 had their lives changed by it.

But not Mendel. He simply kept on working at the abbey, tending to the gardens, just as he did when Prussia invaded Brno in 1866. Just as he did when the Austrian Empire transformed into Austria-Hungary a year later.

It says something when a man can pass through history while leaving such little mark on it. And it makes you think. Who’s to say there’s not another Gregor Mendel out there right now, utterly anonymous to all but the members of one little society in the minor city he lives in, beavering away at research that will one day utterly transform our lives.

The story of Gregor Mendel then is not just the story of one man and his peas. It’s the story of how ideas persist, how great breakthroughs can survive even when the mind behind them dies in obscurity.

Gregor Mendel is rightly famous today. Who the next Mendel might be – and what life-changing research they may be doing – is something we will have to wait and see.

Sources:

BBC In Our Time podcast on genetics: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00547md

Naked Scientists podcast: https://www.thenakedscientists.com/podcasts/naked-genetics/mendels-trick

Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Gregor-Mendel

Mendel Museum timeline: https://mendelmuseum.muni.cz/en/g-j-mendel/zivotopis

Biography’s take: https://www.biography.com/scientist/gregor-mendel

Smithsonian explains: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/evolution-world-tour-mendels-garden-czech-republic-6088291/

Mendel and Darwin (plus various details): https://www.irishtimes.com/news/science/inherited-wealth-the-genius-of-george-mendel-the-father-of-genetics-1.2670290

Interesting overview of Mendel’s lectures: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4299709/

Context of genetics: https://history.nih.gov/exhibits/nirenberg/hs1_mendel.htm

A heavy crash-course in genetics: https://www.britannica.com/science/genetics

Janacek at the Abbey: https://www.leosjanacek.eu/en/augustinian-abbey/

William Bateson; https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Bateson

Thomas Hunt Morgan: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Thomas-Hunt-Morgan