“He could have added fortune and fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world.”

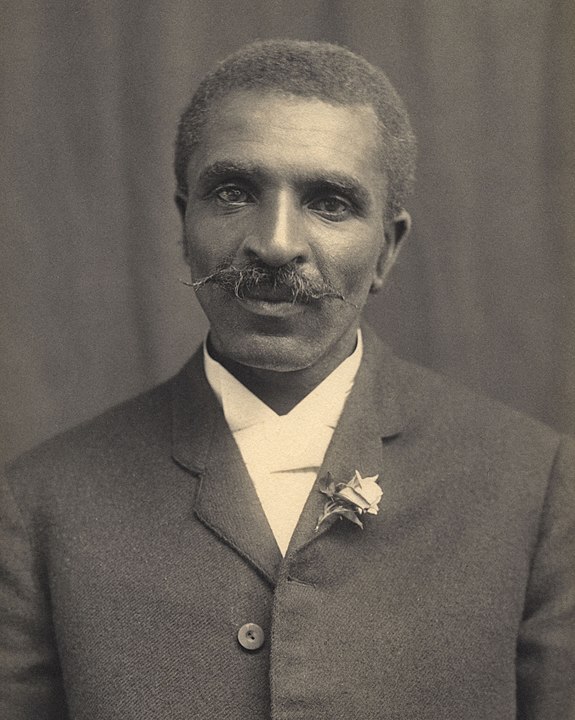

Those words are found on the gravestone of George Washington Carver, an inspirational scientist who was once dubbed by TIME Magazine as the “Black Leonardo.” This was apropos as Carver regarded himself more of an artist who used natural things rather than a true scientist. “Cook-stove chemists” was how he jokingly referred to himself and his research team.

At a time of high racial tensions, when he was part of a community that was still heavily marginalized and discriminated against, the talent and achievements of George Carver transcended all color barriers and were appreciated by the entire nation.

And, despite all this, most simply remember him as the “Peanut Man.” His work with peanuts brought him the most success, although even by Carver’s own admission, it was not his greatest work. But everything he did, he did with a purpose – to help “the furthest man down.” Today, we take a look at the full extent of the career and legacy of George Washington Carver.

Early Years & Education

George Washington Carver was born in a small town called Diamond Grove in Newton County, Missouri, today known simply as Diamond. His birth date is a mystery. Because he was born into slavery, the exact date was never recorded. It was sometime during the mid 1860s, but before slavery was abolished in January 1865. Later, Carver said that it happened “near the end of the war” so 1864 is generally given as his year of birth.

Right from the very beginning, Carver experienced great tragedy and we’re talking about more than the obvious misery of being born a slave. His parents were Mary and Giles and they were owned by a German-American immigrant named Moses Carver. His father died before he was born and when George was just an infant, he, his mother, and older sister were kidnapped by bushwackers and taken to be sold in Arkansas.

Moses Carver hired a man to get them back, but he was only able to track down and recover George in exchange for a horse. Afterwards, slavery may have been abolished, but the boy was still an orphan. Fortunately for him, Moses Carver and his wife Susan took in George and his older brother James and raised them as their own.

George was a frail child and was often sick during his childhood. Therefore, he was too weak to work on the farm with Moses and James so, instead, he helped Susan Carver around the home by doing chores, cooking, and tending the garden. During their free time, Susan taught him to read and write. He showed an intellectual aptitude from a young age and his adoptive guardians encouraged him to pursue an education.

Around the age of 12, George wanted to enroll in school. However, he couldn’t do that in Diamond Grove because it only had one public school and it did not accept black pupils. Instead, he traveled to the county seat of Neosho about ten miles away. From this point on, he left the Carver farm, more or less. He would sometimes return and stay for a weekend but, other than that, he kept moving from one place to another to further his education. It was also in Neosho that he first started going by “George Carver” as, up until that point, he kept referring to himself as “Carver’s George.” The “Washington” he added later in honor of a man who played an important role in his life.

Due to discrimination, Carver had to jump from one school to the next before finding acceptance. He eventually managed to obtain a high school diploma after graduating from Minneapolis High School in Minneapolis, Kansas.

From there, George wanted to move on to college. After being rejected by most of the institutions he applied for, Carver was finally accepted sight unseen by Highland College in Kansas, but they, too, later rejected him once they discovered that he was black.

Feeling a bit discouraged, George gave up his dream of going to college for a while and, instead, claimed a homestead which he farmed alone, while simultaneously doing odd jobs and working as a ranch hand to support himself. He did this for a few years but, by the late 1880s, Carver was ready to move on to something else. He managed to secure a loan from a bank and he left Kansas, making his way to Iowa.

In the city of Winterset, he met and befriended a white couple called the Milhollands who urged him to continue his higher education. Although reluctant at first, Carver eventually relented and enrolled in a little Methodist school in Indianola, Iowa, called Simpson College. The time he spent there had a deep effect on George Carver, not just from a career perspective, but also from a spiritual one. It greatly strengthened his Christian faith as he finally found a place which accepted everyone regardless of race and made him “believe [he] was a real human being.”

Carver studied a multitude of subjects at Simpson College but, somewhat unexpectedly, focused mainly on art, particularly painting. This had been a passion of his ever since he was a young man, but his teacher, Etta Budd, did not think that a black man in that day and age had a chance of making a decent living as a painter. When she found out that Carver was also interested in plants, she encouraged him to switch to botany and enroll at the Iowa State Agricultural College in Ames where her father taught horticulture.

Going to Tuskegee

In 1891, George Carver became the first black man accepted at Iowa State University. Now fully living his dream, he embraced all facets of campus life. Carver was on the debate club, the athletics team, he was captain of the campus military regiment, he wrote poetry published in the student newspaper and two of his paintings were even exhibited at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893.

But, of course, it was his agricultural work that earned him the most praise. After presenting his thesis in 1894 titled “Plants as Modified by Man,” Carver graduated and continued to study for his master’s degree. His professors were so impressed with his work that they asked him to begin teaching, as well.

His master’s program saw Carver work as assistant botanist for the College Experiment Station, focusing on plant pathology (which is the study of disease in plants) and mycology (which is the study of fungi). During this time, he wrote several papers on his work that were published and started garnering him a reputation as one of the country’s leading young scientists. He completed his master’s degree in 1896.

Now that his education was complete, Carver was ready to embark on a permanent career as teacher and researcher. He wasn’t hurting for offers but, in the end, he chose a young institution in Tuskegee, Alabama, that had only been established 15 years prior. It was the Tuskegee Institute, known today as Tuskegee University, the passion project of prominent civil rights activist Booker T. Washington. Widely influential and respected among the elite circles of American society, Washington wanted to set up a university that could provide a higher education for black people without fear of discrimnation. He founded the Tuskegee Institute in 1881 with the help of donations from industrialists such as Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller.

Around the mid 1890s, Washington had entered the second phase of his vision for his university which was to recruit the most talented black teachers and scientists in the country. Obviously, Carver was on his list and he clearly shared Washington’s vision. In 1896, Carver moved to Alabama where he accepted a position with the Agriculture Department at the Tuskegee Institute, one he would keep for the rest of his life.

You might expect that the pairing of Carver and Washington to be a match made in heaven, but the two actually butted heads quite often. Those who knew them believed they had opposing personalities. Washington was a pragmatist who set a goal and tried to accomplish it as fast as possible. Carver, on the other hand, was more of a dreamer who liked to fritter the time away in his lab, either painting or looking after his plants.

As the director of the newly created Agricultural Experiment Station, George Carver expected his job to mostly involve research which was what he was interested in. However, Washington also wanted him to manage the farms, teach classes, and serve on several committees and councils. It was the bureaucracy and all the paperwork that Carver loathed most of all. He threatened to quit several times during Washington’s tenure as President of the Tuskegee Institute. The latter always managed to smooth things over, but he also flat-out refused to give into some of Carver’s requests such as giving up his teaching duties. Despite their adversarial professional relationship, the two had a healthy respect for each other and always spoke highly of one another. Carver would later even add “Washington” to his name in honor of the civil rights leader.

Besides his spats with the university leadership, Carver wasn’t exactly popular with the other faculty members when he first came in, either. Many of them resented the privileges that Washington offered him in order to get him to come to Tuskegee. This was still in the infancy stages of the university which did not have a lot of space or money to go around. Other faculty members had to live two in one dormitory room if they were unmarried and they made, on average, $400 a year. Carver, on the other hand, had an annual salary of $1,000 plus expenses and got two dormitory rooms all to himself.

How to Improve Your Crops

Despite the various administrative obstacles that Carver encountered during his time at Tuskegee, they did not hamper his effectiveness as a scientist or researcher. He decided that his efforts would best be spent helping the farmers of America, particularly in the southern states because Carver believed that they would suffer in the years and decades that followed due to their over-reliance on cotton.

The practice of growing the same crop in the same place year after year after year is called monocropping. It is a problem because it depletes the soil of the same nutrients over and over again and leads to soil erosion which, in turn, will result in much poorer crop yields in the future. Cotton, for example, is quite a demanding crop that uses up a lot of nitrogen in order to grow.

To alleviate the issue of monocropping, farmers sometimes practiced crop rotation which simply involved alternating between different crops for subsequent growing seasons so that the soil had time to build up its nutrients again. George Carver was a big proponent of crop rotation, but he did not invent it, just to be clear. It had been practiced since ancient times, but farmers from the American South had no interest in it because they regarded cotton as the only cash crop around. Anything else would not have been anywhere near as useful and, therefore, would not have made as much money.

At first, Carver presented other ideas, such as suggesting that farmers use commercial fertilizer with a high nitrogen content or that they buy a second horse and use a two-horse plow which would till the soil deeper. These suggestions were seen as a bit tone-deaf, coming from someone who didn’t truly grasp the situation in the South. It wasn’t that farmers were unaware of these solutions, or that they were ignorant to the problems caused by monocropping, but that they did not have any money to do anything about it.

The farmers that Carver aimed to help were all poor, and many of them were black. Following the abolition of slavery, wealthy landowners gave them parcels of land which they could work in exchange for a set fee or a percentage of the crop. Their profit margins were razor thin and even just one bad growing season could cause them to lose everything and plunge them into crippling debt. They had very few land rights and were up against a system which was completely stacked against them. It was a “system of near slavery,” as one historian described it. Therefore, since the land was never truly theirs, anyway, the farmers had almost no incentive to care about the health of the soil, let alone spend whatever money they saved up in order to improve it.

Carver soon realized the extent of the issues that plagued the poor southern farmers so his research focused on other ways to improve their work that did not necessarily require any serious investments. In this regard, almost all of the ideas he had while working at Tuskegee were published in the form of bulletins. He issued 44 of these bulletins between 1898 and 1943. The first one, for example, was titled “Feeding Acorns” and it simply encouraged farmers to use acorns to fatten up their livestock as a cheaper alternative to corn that, otherwise, typically went to waste. Carver’s most popular bulletin was No. 31 from 1916 which saw multiple reprintings. Titled “How to Grow the Peanut & 105 Ways of Preparing It for Human Consumption,” it was a list of recipes collected from other cookbooks, magazines, newspapers, and agricultural bulletins.

Carver’s educational efforts did not consist solely of these bulletins. He still felt that his information was not reaching all of its intended audience, mainly because a lot of the farmers were illiterate or simply because they were not expecting any kind of actual help from an official institution. Carver decided that he needed a more direct way to bring education to these people and, thus, the Jesup Agricultural Wagon was born.

Founded in 1906 by George Carver, this was the first step in the Movable School outreach program of the Tuskegee Institute and was named after New York banker Morris Ketchum Jesup who funded the program. These wagons would travel from farm to farm with equipment and instructional charts and give lectures to farmers on how to improve the quality of their soil and alternate cotton with other crops. It proved successful enough that the United States Department of Agriculture eventually adopted it for their own outreach program.

The Peanut Man

In order to convince farmers to willingly switch out their cotton with other crops, Carver needed to show them that it was possible for them to make a living by growing other things. Thus he embarked on a new mission which was to research and develop new applications for crops that he felt had been overlooked.

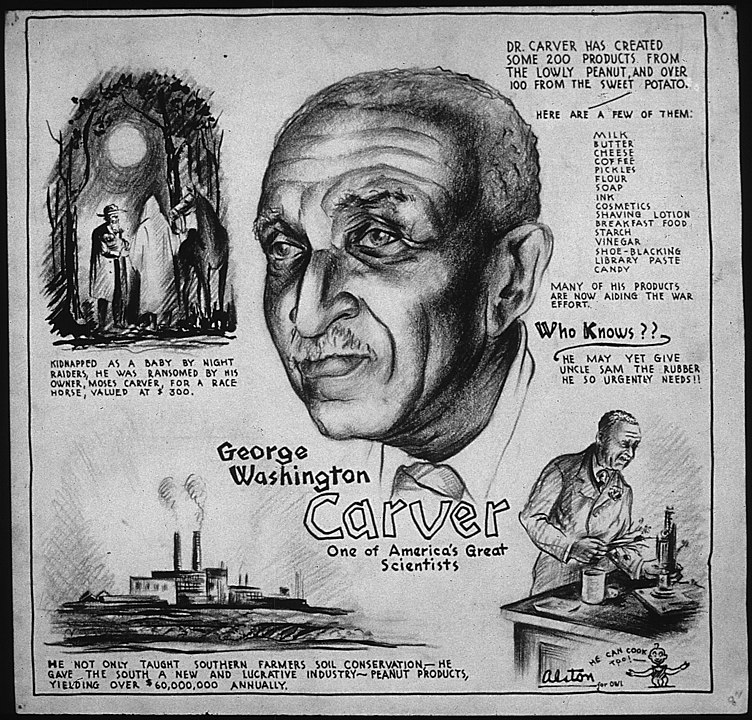

Of course, we all know about the most famous one of all – the peanut. In the minds of many, finding 300 uses for the peanut is still Carver’s main claim to fame. One of the main reasons why the agricultural scientist focused on this legume was because the peanut was quite adept at repairing the damage done to the soil by cotton. Not only did it have meager nitrogen needs, but it could also grow with relatively little water consumption.

As we already mentioned, 105 of those 300 uses were food recipes which he presented in his most popular bulletin. They included: flour, chili sauce, dry coffee, instant coffee, chop suey sauce, mayonnaise, meat loaf, salad oil, buttermilk, mock chicken, mock duck, mock goose, vinegar, caramel, cheese pimento, peanut wafers, and many, many more.

Of course, that was just the tip of the peanutty iceberg. Carver also showed that the legume could be used to make various types of feed for livestock, plus a dozen different types of beverages. He used it for medicines such as rubbing oils, tonics, and laxatives; and numerous cosmetics such as shampoo, hand & face lotions, shaving cream, soap, pomade, and dandruff cures.

The peanut was useful around the house, as well. Carver turned it into laundry soap, leather dyes, paints, wood stains, insecticide, various types of paper, metal polish, diesel fuel and gasoline, rubber, ink, linoleum, axle grease, lubricating oil, and insulating board.

As you can see, the peanut was an all-purpose, practical crop, but almost none of these ideas actually took off. Some of them had already been around for a while. After all, Carver made no pretense to have come up with all of them, nor did he argue that they were superior to their alternatives. That was not the point. Carver’s goal was to show southern farmers, and the country as a whole, that it was possible to develop other cash crops apart from cotton.

Given that Carver’s hundreds of uses for peanuts never became very popular, it is a little strange that the two are so inexorably linked. Historians point the finger at an obscure event from Carver’s life when he gave an impassioned testimony before Congress. It was the moment that permanently connected the scientist to the legume in the public mind, but then the event itself was forgotten so, nowadays, people remember the connection, but not its origins. Back in 1921, the U.S. Government wanted to place a tariff on imported peanuts. Carver testified before the U.S. House Ways and Means Committee and gave a dazzling speech to support the tariff in order to bolster the nation’s own growth of peanuts. The tariff was passed and, afterwards, Carver became somewhat of a media sensation.

One more thing that should be specified about George Washington Carver’s nutty career is that he did not invent peanut butter. This might be a common belief, but it is incorrect as peanut butter already existed by the time he started publishing his bulletins. In fact, the oldest references to the salty snack go all the way back to the Aztecs and the Incas who made a paste out of ground up roasted peanuts. The first to make modern peanut butter was Canadian chemist Marcellus Gilmore Edson who patented peanut-candy, as he called it, in 1884. The process was later refined by John Harvey Kellogg of Kellogg’s cereal fame and, in 1903, Dr. Ambrose Straub invented a machine especially designed to make peanut butter.

Legacy & Last Years

According to Carver himself, his research into peanuts was not the greatest work of his career. Even so, he never actively discouraged anyone from making the association between the two which is why he is still so closely associated with the legume even today. He didn’t mind the fame that he enjoyed in the last decades of his life after his testimony before Congress. He believed that he could use it to advance his causes, to promote the Tuskegee Institute and to encourage more racial integration.

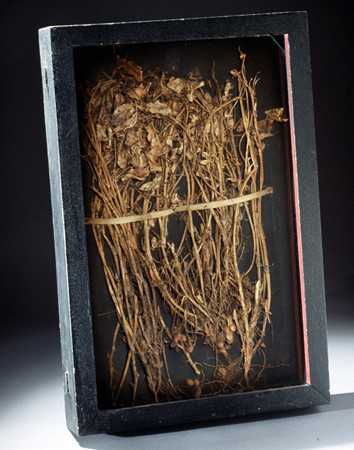

Carver’s research into sustainable farming ended up saving countless farmers from ruin when the boll weevil ravaged the southern cotton crops at the start of the 20th century. This ravenous pest made its way from Mexico around 1892 and, in just a couple of decades, turned into a major threat not only to all the cotton crops in the country, but the economy which was completely reliant on them. This “wave of evil,” as it was dubbed by the USDA, did not succeed in destroying the financial state of the South thanks to George Carver and others like him who advocated for crop diversification. Peanut plantation expanded from 500,000 acres in 1916 to over four million acres in 1918 and continued growing from there. The city of Enterprise, Alabama, even has a monument dedicated to the boll weevil, the first such structure in the world made to honor an agricultural pest. They dubbed the insect a “herald of prosperity” and were grateful that it forced the locals to switch to growing peanuts instead of cotton which triggered a period of affluence for the city.

And it wasn’t just peanuts. Although the legume was Carver’s bread and (peanut) butter, if you will, he saw the problem in trying to prevent monocropping by simply switching one crop with another crop. Therefore, he also advocated for the cultivation of other plants such as soybeans and pecans. He was a big supporter of the sweet potato, almost as big as the peanut. He saw many similarities between them in terms of the benefits they would provide to cotton farmers and how easy they were to grow. While Carver wasn’t as imaginative with the sweet potato, he still found over a hundred uses for the root vegetable. They included flour, sugar, starch, vinegar, over a dozen varieties of candy, yeast, dry & instant coffee, sauce, hog feed, alcohol, ink, paper, dyes, paints, and synthetic silk.

Some argue that George Carver’s true legacy was that of a pioneering environmentalist. There is no doubting that the ideas he promoted about sustainability and self-sufficiency had an impact on the world around him, perhaps more significant, if not more well-known, than his work with peanuts.

In his later years, Carver served as agricultural advisor to three U.S. Presidents. He counselled Gandhi on matters of nutrition and agriculture. He taught Henry Ford how to make peanut rubber during World War II. It might be a little hard to pinpoint exactly what George Washington Carver should be remembered for, but when he talked, people listened.

He died on January 5, 1943, approximately 79 years old. Afterwards, there was talk of establishing a national monument in his honor but, due to World War II, all such non-essential expenditures were banned by presidential order. However, a senator from his home state of Missouri sponsored a bill to make an exception in order “to do honor to one of the truly great Americans.” That senator was future President Harry S. Truman and his bill was passed in both houses unanimously.